Przemyśl

Przemyśl (Polish: [ˈpʂɛmɨɕl] (![]() listen); German: Premissel; Yiddish: פשעמישל, romanized: Pshemishl; Ukrainian: Перемишль, romanized: Peremyshl) is a city in southeastern Poland with 60,442 inhabitants, as of June 2020.[1] In 1999, it became part of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship; it was previously the capital of Przemyśl Voivodeship.

listen); German: Premissel; Yiddish: פשעמישל, romanized: Pshemishl; Ukrainian: Перемишль, romanized: Peremyshl) is a city in southeastern Poland with 60,442 inhabitants, as of June 2020.[1] In 1999, it became part of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship; it was previously the capital of Przemyśl Voivodeship.

Przemyśl | |

|---|---|

Przemyśl Cathedral with the city in the background | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Przemyśl  Przemyśl | |

| Coordinates: 49°47′N 22°46′E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | c. 8th century |

| Town rights | 1389 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Wojciech Bakun |

| Area | |

| • Total | 44 km2 (17 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 60,442 |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 37–700 to 37–720 |

| Area code(s) | +48 016 |

| Car plates | RP |

| Website | www |

Przemyśl owes its long and rich history to the advantages of its geographic location. The city lies in an area connecting mountains and lowlands known as the Przemyśl Gate (Brama Przemyska), with open lines of transportation, and fertile soil. It also lies on the navigable San River. Important trade routes that connect Central Europe from Przemyśl ensure the city's importance.

Names

Different names in various languages have identified the city throughout its history. Selected languages include: Bulgarian: Пшемишъл (Pshemishǎl); Czech: Přemyšl; German: Premissel, Prömsel, Premslen; Latin: Premislia; Ukrainian: Перемишль (Peremyshlj) / Ukrainian: Пшемисль (Pshemyslj); and Yiddish: פּשעמישל (Pshemishl).

History

Origins

Przemyśl is the second-oldest city (after Kraków) in southern Poland, dating back to at least the 8th century, when it was the site of a fortified grod belonging to the Lendians (Lendizi), a West Slavic tribe. [3] In the 9th century, the fortified settlement and the surrounding region became part of Great Moravia. Most likely, the city's name dates back to the Moravian period. Also, archeological remains testify to the presence of a Christian monastic settlement as early as the 9th century.

Upon the invasion of the Hungarian tribes into the heart of the Great Moravian Empire around 899, the local Lendians declared allegiance to the Hungarians. The region then became a site of contention between Poland, Rus and Hungary beginning in at least the 9th century, with Przemyśl along with other Cherven Grods, falling under the control of the Polans (Polanie), who would in the 10th century under the rule of Mieszko I establish the Polish state. The city was mentioned by Nestor the Chronicler, when in 981 it was captured by Vladimir I of Rus.[4][5] In 1018, Przemyśl returned to Poland, and in 1031 it was retaken by Rus. Around the year 1069, Przemyśl again returned to Poland, after Bolesław II the Generous retook the town and temporarily made it his residence. In 1085, the town became the capital of a semi-independence Principality of Peremyshl under the lordship of Rus.

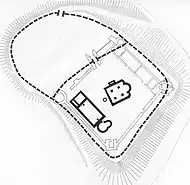

The palatium complex including a Latin rotunda was built during the rule of the Polish king Bolesław I the Brave in the 11th century.[6] Sometime before 1218, an Orthodox eparchy was founded in the city.[7] Przemyśl later became part of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia.

Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

.jpg.webp)

In 1340, Przemyśl was retaken by the king Casimir III of Poland and again became part of the Kingdom of Poland as result of the Galicia–Volhynia Wars. Around this time, the first Roman Catholic diocese was founded in the city,[7] and Przemyśl was granted a city charter based on Magdeburg rights, confirmed in 1389 by the king Władysław II Jagiełło. The city prospered as an important trade centre during the 16th century. Like nearby Lwów, the city's population consisted of a great number of nationalities, including Poles, Jews, Germans, Czechs, Armenians and Ruthenians. The long period of prosperity enabled the construction of public buildings such as the Renaissance town hall and the Old Synagogue of 1559. Also, a Jesuit college was founded in the city in 1617.[7]

The prosperity came to an end in the middle of the 17th century, caused by the invading Swedish army during the Deluge, and a general decline of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The city decline lasted for over a hundred years, and only at the end of the 18th century did it recover its former levels of population. In 1754, the Roman Catholic bishop founded Przemyśl's first public library, which was only the second public library in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, with Warsaw's Załuski Library founded 7 years earlier. Przemyśl's importance at that time was such that when Austria annexed eastern Galicia in 1772 the Austrians considered making Przemyśl their provincial capital, before deciding on Lwów.[7] In the mid-18th century, Jews constituted 55.6% (1,692) of the population, Roman Catholic Poles 39.5% (1,202), and Greek Catholic Ruthenians 4.8% (147).[8]

Part of Austrian Poland

.JPG.webp)

In 1772, as a consequence of the First Partition of Poland, Przemyśl became part of the Austrian empire, in what the Austrians called the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. According to the Austrian census of 1830, the city was home to 7,538 people of whom 3,732 were Roman Catholic, 2,298 Jews and 1,508 were members of the Greek Catholic Church, a significantly larger number of Ruthenians than in most Galician cities.[7] In 1804, a Ruthenian library was established in Przemyśl. By 1822, its collection had over 33,000 books and its importance for Ruthenians was comparable to that held by the Ossolineum library in Lwów for Poles. Przemyśl also became the center of the revival of Byzantine choral music in the Greek Catholic Church. Until eclipsed by Lviv in the 1830s, Przemyśl was the most important city in the Ruthenian cultural awakening in the nineteenth century.[7]

In 1861, the Galician Railway of Archduke Charles Louis built a connecting line from Przemyśl to Kraków, and east to Lwów. In the middle of the 19th century, due to the growing conflict between Austria and Russia over the Balkans, Austria grew more mindful of Przemyśl's strategic location near the border with the Russian Empire. During the Crimean War, when tensions mounted between Russia and Austria, a series of massive fortresses, 15 km (9 mi) in circumference, were built around the city by the Austrian military.

The census of 1910, showed that the city had 54,078 residents. Roman Catholics were the most numerous 25,306 (46.8%), followed by Jews 16,062 (29.7%) and Greek Catholics 12,018 (22.2%).[9]

World War I (Przemyśl Fortress)

With technological progress in artillery during the second half of the 19th century, the old fortifications rapidly became obsolete. The longer range of rifled artillery necessitated the redesign of fortresses so that they would be larger and able to resist the newly available guns. To achieve this, between the years 1888 and 1914 Przemyśl was turned into a first-class fortress, the third-largest in Europe out of about 200 that were built in this period. Around the city, in a circle of circumference 45 km (28 mi), 44 forts of various sizes were built. The older fortifications were modernised to provide the fortress with an internal defence ring. The fortress was designed to accommodate 85,000 soldiers and 956 cannons of all sorts, although eventually 120,000 soldiers were garrisoned there.[10]

In August 1914, at the start of the First World War, Russian forces defeated Austro-Hungarian forces in the opening engagements and advanced rapidly into Galicia. The Przemyśl fortress fulfilled its mission very effectively, helping to stop a 300,000 strong Russian army advancing upon the Carpathian Passes and Kraków, the Lesser Poland regional capital. The first siege was lifted by a temporary Austro-Hungarian advance. However, the Russian army resumed its advance and initiated a second siege of the fortress of Przemyśl in October 1914. This time relief attempts were unsuccessful. Due to lack of food and exhaustion of its defenders, the fortress surrendered on 22 March 1915. The Russians captured 126,000 prisoners and 700 big guns. Before the surrender, the complete destruction of all fortifications was carried out. The Russians did not linger in Przemyśl. A renewed offensive by the Central Powers recaptured the destroyed fortress on 3 June 1915. During the fighting around Przemyśl, both sides lost up to 115,000 killed, wounded, and missing.[10]

Inter-war years

Population of Przemyśl, 1931

| Roman Catholics | 39 430 | (63,3%) |

| Jews | 18 376 | (29,5%) |

| Greek Catholics | 4 391 | (7,0%) |

| Other denominations | 85 | (0,2%) |

| Total | 62 272 |

At the end of World War I, Przemyśl became disputed between renascent Poland and the West Ukrainian People's Republic. On 1 November 1918, a local provisional government was formed with representatives of Polish, Jewish, and Ruthenian inhabitants of the area. However, on 3 November, a Ukrainian military unit overthrew the government, arrested its leader and captured the eastern part of the city. The Ukrainian army was checked by a small Polish self-defence unit formed of World War I veterans. Also, numerous young Polish volunteers from Przemyśl's high schools, later to be known as Przemyśl Orlęta, The Eaglets of Przemyśl (in a similar manner to more famous Lwów Eaglets), joined the host. The battlefront divided the city along the river San, with the western borough of Zasanie held in Polish hands and the Old Town controlled by the Ukrainians. Neither Poles nor Ukrainians could effectively cross the San river, so both opposing parties decided to wait for a relief force from the outside. That race was won by the Polish reinforcements and the volunteer expeditionary unit formed in Kraków arrived in Przemyśl on 10 November 1918. When the subsequent Polish ultimatum to the Ukrainians remained unanswered, on 11–12 November the Polish forces crossed the San and forced out the outnumbered Ukrainians from the city in what became known as the 1918 Battle of Przemyśl.

After the end of the Polish–Ukrainian War and the Polish–Bolshevik War that followed, the city became a part of the Second Polish Republic. Although the capital of the voivodship was in Lwów (see: Lwów Voivodeship), Przemyśl recovered its nodal position as a seat of local church administration, as well as the garrison of the 10th Military District of the Polish Army — a staff unit charged with organizing the defence of roughly 10% of the territory of pre-war Poland. As of 1931, Przemyśl had a population of 62,272 and was the biggest city in southern Poland between Kraków and Lwów.

World War II

During the invasion of Poland, the German and Polish armies fought the Battle of Przemyśl in and around the city. The four-day battle was followed by three days of massacres carried out by the German soldiers and police against hundreds of Jews who lived in the city. In total, over 500 Jews were murdered in and around the city and the vast majority of the city's Jewish population was deported across the San River into the portion of Poland that was occupied by the Soviet Union.[11] The border between the two invaders ran through the middle of the city along the San River until June 1941. During the Soviet occupation Przemyśl was incorporated to the Ukrainian SSR in the atmosphere of NKVD terror[12] as thousands of Jews were ordered to be deported.[11] It became part of the newly established Drohobych Oblast.[13] In 1940, the city became an administrative center of Peremyshl Uyezd with the Peremyshl Fortified District established along the Nazi-Soviet frontier before the German attack against the USSR in 1941.[14]

The town's population increased due to a large influx of Jewish refugees from the General Government who sought to cross the border to Romania.[15] It is estimated that by mid-1941 the Jewish population of the city had grown to roughly 16,500. In the Operation Barbarossa of 1941, the eastern (Soviet) part of the city was also occupied by Germany. On 20 June 1942, the first group of 1,000 Jews was transported from the Przemyśl area to the Janowska concentration camp, and on 15 July 1942 a Nazi ghetto was established for all Jewish inhabitants of Przemyśl and its vicinity – some 22,000 people altogether. Local Jews were given 24 hours to enter the Ghetto. Jewish communal buildings, including the Tempel Synagogue and the Old Synagogue were destroyed; the New Synagogue, Zasanie Synagogue, and all commercial and residential real estate belonging to Jews were expropriated.[16]

The ghetto in Przemyśl was sealed off from the outside on 14 July 1942. By that time, there may have been as many as 24,000 Jews in the ghetto. On 27 July the Gestapo notified Judenrat about the forced resettlement program and posted notices that an "Aktion" (roundup for deportation to camps) was to be implemented involving almost all occupants. Exceptions were made for some essential, and Gestapo workers, who would have their papers stamped accordingly. On the same day, Major Max Liedtke, military commander of Przemyśl, ordered his troops to seize the bridge across the San river that connected the divided city, and halt the evacuation. The Gestapo were forced to give him permission to retain the workers performing service for the Wehrmacht (up to 100 Jews with families). For the actions undertaken by Liedtke and his adjutant Albert Battel in Przemyśl, Yad Vashem later named them "Righteous Among the Nations".[17] The process of extermination of the Jews resumed thereafter. Until September 1943 almost all Jews were sent to the Auschwitz or Belzec extermination camps. The local branches of the Polish underground and the Żegota managed to save 415 Jews. According to a postwar investigation in German archives, 568 Poles were executed by the Germans for sheltering Jews in the area of Przemyśl, including Michał Kruk, hanged along with several others on 6 September 1943 in a public execution. Among the many Polish rescuers there, were the Banasiewicz, Kurpiel, Kuszek, Lewandowski, and Podgórski families.

The Red Army retook the town from German forces on 27 July 1944. On 16 August 1945, a border agreement between the government of the Soviet Union and the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity, installed by the Soviets, was signed in Moscow. According to the so-called Curzon Line, the postwar eastern border of Poland has been established several kilometres to the east of Przemyśl.

Post-war years

In the postwar territorial settlement, the new border between Poland and the Soviet Union placed Przemyśl just within the Polish People's Republic. The border now ran only a few kilometres to the east of the city, cutting it off from much of its economic hinterland. Due to the murder of Jews in the Nazi Holocaust and the postwar expulsion of Ukrainians (in the Operation Vistula or akcja Wisła), the city's population fell to 24,000, almost entirely Polish. However, the city welcomed thousands of Polish migrants from Kresy (Eastern Borderlands) who were expelled by the Soviets — their numbers restored the population of the city to its prewar level.

Climate

The climate is warm-summer humid continental (Köppen: Dfb). Despite its location in southern Poland, its winters may be colder than at higher latitudes, especially in the north-west of the country due to continentality.[18]

| Climate data for Przemyśl | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

15 (59) |

24 (75) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

30 (86) |

20 (68) |

16 (61) |

37 (99) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0 (32) |

1 (34) |

6 (43) |

13 (55) |

19 (66) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

14 (57) |

6 (43) |

3 (37) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−6 (21) |

−2 (28) |

3 (37) |

8 (46) |

12 (54) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

5 (41) |

1 (34) |

−2 (28) |

4 (39) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37 (−35) |

−27 (−17) |

−25 (−13) |

−11 (12) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

3 (37) |

0 (32) |

−7 (19) |

−16 (3) |

−17 (1) |

−37 (−35) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 27 (1.1) |

24 (0.9) |

25 (1.0) |

43 (1.7) |

57 (2.2) |

88 (3.5) |

105 (4.1) |

93 (3.7) |

58 (2.3) |

50 (2.0) |

43 (1.7) |

43 (1.7) |

656 (25.8) |

| Source: BBC Weather [19] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Przemyśl (Podwinie), elevation: 279 m or 915 ft, 1961–1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

1.2 (34.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

12.0 (53.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.8 (46.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.0 (−22.0) |

−30.4 (−22.7) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−30.4 (−22.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29 (1.1) |

29 (1.1) |

34 (1.3) |

48 (1.9) |

76 (3.0) |

97 (3.8) |

100 (3.9) |

77 (3.0) |

55 (2.2) |

42 (1.7) |

40 (1.6) |

40 (1.6) |

667 (26.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 103.7 |

| Source: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

Main sights

Due to the long and rich history of the city, there are many sights in and around Przemyśl, of special interest to tourists, including the Old Town with Rynek, the main market square.

Among the historic buildings and museums, opened to visitors, are:

- Muzeum Narodowe (the National Museum), contains a collection of icons, second only to the one in Sanok in size

- Muzeum Dzwonów i Fajek (the Museum of Bells and Pipes)

- Muzeum Diecezjalne (the diocesan museum)

- Reformed Franciscan church and monastery, founded in 1627

- Franciscan Church, from mid-18th-century in a baroque style

- Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, Przemyśl, former 17th-century Jesuit church, now a Ukrainian Greek Catholic cathedral

- Carmelite Church, 17th century late-Renaissance church

- The Great Przemyśl Cathedral

- Przemyśl Castle, built by Casimir III the Great in the 14th century

- Zasanie Synagogue

- New Synagogue (Przemyśl)

- Lubomirski Palace, an eclectic style palace of the Lubomirski family constructed in 1885

- Kopiec Tatarski, a mound to the south of the city where a 16th-century Tatar khan was supposedly buried. The Tatarska Góra TV tower is built on the mound.

- World War I cemeteries (Cmentarz Wojskowy)

- Civil Defense Shelter – Schron Kierowania Obroną Cywilną[21]

Education

- Wyższa Szkoła Administracji i Zarządzania

- Wydział zamiejscowy w Rzeszowie

- Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarcza

- Wyższa Szkoła Informatyki i Zarządzania

- Nauczycielskie Kolegium Języków Obcych

- Nauczycielskie Kolegium Języka Polskiego

Sport

- Czuwaj Przemyśl – football club

- AZS Czuwaj Przemyśl – handball club

- Polonia Przemyśl – football club

Politics

Krosno/Przemyśl constituency

Members of Sejm elected from Krosno/Przemyśl constituency

Law and Justice

Marek Kuchciński

Anna Schmidt-Rodziewicz

Piotr Uruski (SP)

Maria Kurowska (SP)

Piotr Babinetz

Teresa Pamuła

Adam Śnieżek

Tadeusz Chrzan

Civic Coalition

Joanna Frydrych (PO)

Marek Rząsa (PO)

Twin towns

Przemyśl is twinned with:

Eger, Hungary

Eger, Hungary South Kesteven, United Kingdom

South Kesteven, United Kingdom Paderborn, Germany

Paderborn, Germany Lviv, Ukraine

Lviv, Ukraine Truskavets, Ukraine

Truskavets, Ukraine Kamyanets-Podilskyi, Ukraine

Kamyanets-Podilskyi, Ukraine Chivasso, Italy

Chivasso, Italy

Notable people

- Jerzy Bartmiński (b.1939), Polish linguist and ethnologist, lecturer at the UMCS

- Avraham Ben-Yitzhak (1883–1950), Israeli poet

- Svetozar Boroević (1856–1920), Austro-Hungarian Army Marshal

- Jan Borukowski, Bishop of Przemyśl, (1524–1584)

- Helene Deutsch, née Rosenbach (1884–1982), Polish-American psychoanalyst

- Andrzej Maksymilian Fredro (c.1620–1679), Sejm Marshal

- Mark Gertler (1891–1939), British painter

- Leonid Gobyato (1875–1915), Russian military designer

- Stefan Grabiński (1887–1936), Polish writer

- Giulietta Guicciardi (1782–1856), Austrian countess

- Joshua Höschel ben Joseph (1578–1648), Polish rabbi

- Wojciech Inglot (1955–2013), Polish entrepreneur, founder of Inglot Cosmetics Company

- Hermann Kusmanek von Burgneustädten (1860–1934), Colonel-General of the Austrian Imperial Army

- Czesław Marek (1891–1985) Polish composer, pianist, and piano teacher

- Yaroslav Osmomysl (ca. 1135–1187), Prince of Halych

- Jerzy Podbrożny (b. 1966), Polish footballer

- Stefania Podgórska (1925–2018), Polish holocaust resister, Righteous Among the Nations

- Jan Nepomucen Potocki (1867–1943), Polish nobleman

- Teodor Andrzej Potocki (1664–1738), Polish nobleman, Primate of Poland

- Hieronim Florian Radziwiłł (1715–1760), Polish–Lithuanian nobleman

- Jaroslav Rudnyckyj (1910–1995), Ukrainian-Canadian linguist

- Pawel Sek (b. 1977), Polish music producer and composer

- Ryszard Siwiec (1909—1968), Polish accountant and former Home Army resistance member

- Renia Spiegel (1924–1942), Polish-born Jewish diarist

- Zeev Sternhell (b. 1935), Polish-born Israeli historian, political scientist and commentator

- Andrzej Trzebicki (1607–1679), Polish nobleman, bishop of Kraków

- Anatole Vakhnianyn (1841–1908), Ukrainian political and cultural figure, composer, teacher and journalist

- Jan Wężyk (1575–1638), Polish nobleman, Primate of Poland

- Andrzej Tomasz Zapałowski (b. 1966), Polish politician and a former Member of the European Parliament (MEP)

- Władysław Dominik Zasławski (ca. 1616 – 1656), Polish nobleman of Ruthenian origin

- Velvel Zbarjer (1824–1884), Galician Jewish Brody singer

- Samuel Zborowski (?–1584), Polish military commander

- Zyndram of Maszkowice (c. 1355–c. 1414), Polish knight

- Eli Herschel Wallach was born on December 7, 1915 at 156 Union Street in Red Hook, Brooklyn, a son of Jewish immigrants Abraham and Bertha (Schorr) Wallach from Przemyśl (now Poland). He had a brother and two sisters

See also

- Old Synagogue in Przemyśl destroyed by the Nazis in 1941

- Przemyślanin

References

- "Population. Size and structure by territorial division". © 1995–2009 Central Statistical Office 00-925 Warsaw, Al. Niepodległości 208. 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- Przemysław Wiszewski. Domus Bolezlai: Values and Social Identity in Dynastic Traditions of Medieval Poland (c. 966–1138). BRILL. 2010. p. 445.

- Poleski, Jacek (2000). "Naszacowice". In Wieczorek, Alfried; Hinz, Hans-Martin (eds.). Europe's Centre Around AD 1000. Theiss. p. 175. ISBN 978-3806215496.

- Under 981, the Primary Chronicle reports on Volodymyr's campaign against the Poles, which resulted in the capture of "their towns" Peremyshl and Cherven. As the chronicler notes, they remained under Rus' control until his own time. In: S. Plokhy. "The origins of the Slavic nations: premodern identities in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus". Cambridge University Press, 2006. p. 57.

- A. Buko. "The archaeology of early medieval Poland". Brill. 2008. pp. 307–308

- Przemysław Wiszewski. Domus Bolezlai: Values and Social Identity in Dynastic Traditions of Medieval Poland (c. 966–1138). BRILL. 2010. p. 445.

- Stanislaw Stepien. (2005). Borderland City: Przemyśl and the Ruthenian National Awakening in Galicia. In Paul Robert Magocsi (Ed.). Galicia: A Multicultured Land. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 52–67

- J. Motylkiewicz. "Ethnic Communities in the Towns of the Polish-Ukrainian Borderland in the Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries". C. M. Hann, P. R. Magocsi ed. Galicia: A Multicultured Land. University of Toronto Press. 2005. p. 37.

- Juraj Buzalka. Nation and Religion: The Politics of Commemorations in South-East Poland. LIT Verlag Münster. 2008. p. 34

- Tom Idzikowski. "The History of the Construction of the Fortress of Przemyśl". Engagements and Battles. Austro-Hungarian-army.co.uk. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team, Przemysl, http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/przemysl.html

- Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. p. 74. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- Voytovych, L. Drohobych Oblast. "Lviv Gazette". 18 July 2013

- Koval, M. Unknown Ukraine: 20th century history of fortifications. Myths and reality.

- Encyclopedia of the Ghettos (2016). "סמבּוֹר (Sambor) המכון הבין-לאומי לחקר השואה – יד ושם". The International Institute for Holocaust Research. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Virtual Shtetl (2016). "Jewish history of Przemyśl. The Holocaust". POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14.

- Daniel Fraenkel (2005). Akte 1979. Battel, Albert. Die deutschen Gerechten. Deutsche und Österreicher. Wallstein Verlag. pp. 65–. ISBN 9783892449003. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- "Przemyśl climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Przemyśl weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- "Average Conditions Przemyśl, Poland". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- "Przemyśl (12695) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "Schron Kierowania Obroną Cywilną – Visit Przemyśl". visit.przemysl.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2017-07-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Przemyśl. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Przemyśl. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Przemyśl. |

- (in Polish) Municipal website

- (in Polish) Powiat of Przemyśl (Przemyśl County)

- (in Polish) Przemyśl 24/7

- (in Polish) Photo-blog about Przemyśl

- Przemyśl on old postcards

- Przemyśl Photo Gallery

- The Jewish Przemyśl Blog, its Sons and Daughters

- Przemyśl at KehilaLinks

- Przemyśl, Poland at JewishGen

.jpg.webp)