Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park

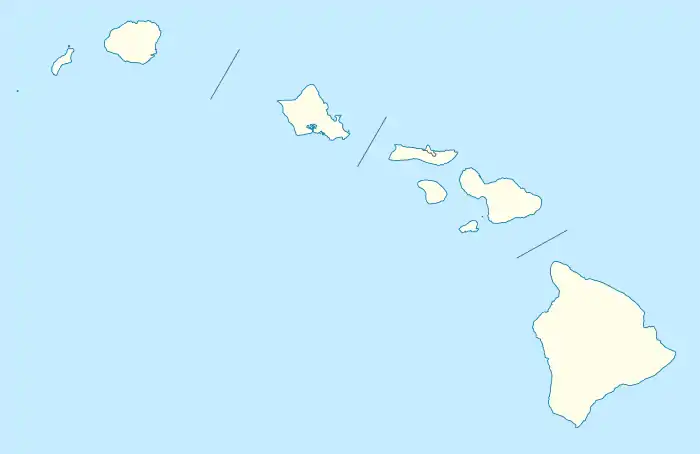

Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park located on the west coast of the island of Hawaiʻi in the U.S. state of Hawaii. The historical park preserves the site where, up until the early 19th century, Hawaiians who broke a kapu (one of the ancient laws) could avoid certain death by fleeing to this place of refuge or puʻuhonua. The offender would be absolved by a priest and freed to leave. Defeated warriors and non-combatants could also find refuge here during times of battle. The grounds just outside the Great Wall that encloses the puʻuhonua were home to several generations of powerful chiefs.

| Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

Reconstructed Hale o Keawe | |

| |

| Location | Hawaii County, Hawaii, United States |

| Nearest city | Holualoa, Hawaiʻi |

| Coordinates | 19°25′19″N 155°54′37″W |

| Area | 420 acres (170 ha) |

| Established | July 26, 1955 |

| Visitors | 421,027 (in 2016)[1] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park |

Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau is one of the only places in Hawaii where the flag of Hawaii can officially fly alone without the American flag; the other three places are ʻIolani Palace, the Mauna ʻAla and Thomas Square.[2][3]

Park name and features

The 420 acre (1.7 km2) site was originally established in 1955 as City of Refuge National Historical Park and was renamed on November 10, 1978. In 2000 the name was changed by the Hawaiian National Park Language Correction Act of 2000 observing the Hawaiian spelling.[4] It includes the puʻuhonua and a complex of archeological sites including: temple platforms, royal fishponds, sledding tracks, and some coastal village sites. The Hale o Keawe temple and several thatched structures have been reconstructed.

Hale o Keawe heiau

The park contains a reconstruction of the Hale o Keawe heiau, which was originally built by a Kona chief named Kanuha in honor of his father King Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku. After the death of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, his bones were entombed within the heiau. The nobility (ali'i) of Kona continued to be buried until the abolition of the kapu system. The last person buried here was a son of Kamehameha I in 1818.

It was believed that additional protection to the place of refuge was received from the mana in the bones of the chiefs. It survived several years after other temples were destroyed. It was looted by Lord George Byron (cousin of the distinguished English poet) in 1825.[5] In 1829, High Chiefess Kapiʻolani removed the remaining bones and hid them in the Pali Kapu O Keōua cliffs above nearby Kealakekua Bay. She then ordered this last temple to be destroyed. The bones were later moved to the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii in 1858.[6]

The entrance to the park.

The entrance to the park. Hawaiian hale (house) at the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park.

Hawaiian hale (house) at the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park. Protector kii (statues) at the Place of Refuge.

Protector kii (statues) at the Place of Refuge.

See also

References

- "National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics". National Park Service. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Clark, John (2019). "The Kamehameha III Statue in Thomas Square". The Hawaiian Journal of History. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 53: 147–149. doi:10.1353/hjh.2019.0008. ISSN 2169-7639. OCLC 60626541.

- Fuller, Landry (August 2, 2016). "Flying high". West Hawaii Today. Kailua-Kona: Oahu Publications, Inc. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Hawaiian National Park Language Correction Act of 2000 (S.939)" (PDF). Govtrack.us. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Rowland Bloxam (1920). "Visit of H.M.S. Blonde to Hawaii in 1825". All about Hawaii: Thrum's Hawaiian annual and standard guide. Thomas G. Thrum, Honolulu: 66–82.

- Alexander, William DeWitt (1894). "The "Hale o Keawe" at Honaunau, Hawaii". Journal of the Polynesian Society. London: E. A. Petherick. 3: 159–161.

- Ward, Greg. 2004, The Rough Guide to Hawaii. Rough Guides.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park. |

| External video | |

|---|---|

Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park travel guide from Wikivoyage- Pu`uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park – National Park Service official site

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park

- Photo essay on residences of Hawaiian Kings

- Go Hawaii article about the park with photos(archived)

- Photographs of the reflecting pools at Pu`uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park *Broken Link*