Independence National Historical Park

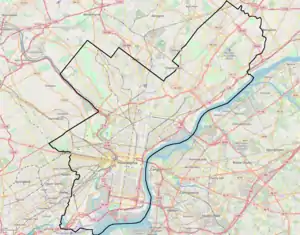

Independence National Historical Park is a federally protected historic district in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States that preserves several sites associated with the American Revolution and the nation's founding history. Administered by the National Park Service, the 55-acre (22 ha)[1] park comprises many of Philadelphia's most-visited historic sites within the Old City and Society Hill neighborhoods. The park has been nicknamed "America's most historic square mile"[3][4][5] because of its abundance of historic landmarks.

| Independence National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

The Liberty Bell with Independence Hall as its backdrop. | |

| Location | Bounded by Chestnut, Walnut, 2nd, and 6th Sts., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39.947778°N 75.148056°W |

| Area | 55.42 acres (22.43 ha)[1] |

| Architect | Strickland, William; Et al. |

| Architectural style(s) | Colonial, Georgian, Federal |

| Visitors | 3,572,770 (in 2011) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Independence National Historical Park |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000683 [2] |

| Designated | June 28, 1948 |

Location of Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia  Independence National Historical Park (Pennsylvania)  Independence National Historical Park (the United States) | |

The centerpiece of the park[6] is Independence Hall, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted in the late 18th century. Independence Hall was the principal meetinghouse of the Second Continental Congress from 1775 to 1783 and the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787.[7]

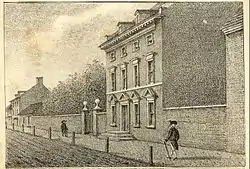

Across the street from Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, an iconic symbol of American independence, is displayed in the Liberty Bell Center. The park contains other historic buildings, such as the First Bank of the United States, the first bank chartered by the United States Congress, and the Second Bank of the United States, which had its charter renewal vetoed by President Andrew Jackson as part of the Bank War. Carpenters' Hall, the site of the First Continental Congress, is located on park property as well, however the building is privately owned and operated. It also contains City Tavern, a recreated colonial tavern, which was a favorite of the delegates and which John Adams felt was the finest tavern in all America.[8][9]

Most of the park's historic structures are located in the vicinity of the four landscaped blocks between Chestnut, Walnut, 2nd, and 6th streets. The park also contains Franklin Court, the site of a museum dedicated to Benjamin Franklin and the United States Postal Service Museum. An additional three blocks directly north of Independence Hall, collectively known as Independence Mall, contain the Liberty Bell Center, National Constitution Center, Independence Visitor Center, and the former site of the President's House. The park also contains other historical artifacts, such as the Syng inkstand which was used during the signings of both the Declaration and the Constitution.

Historical context

Continental Congress and the American Revolution

In response to the Intolerable Acts, which had punished Boston for the Boston Tea Party, the First Continental Congress met at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia from September 5, 1774 to October 26, 1774.[10] The convention organized a pact among the colonies to boycott British goods (the Continental Association) starting December 1, 1774[11] and provided for a Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress assembled at the Pennsylvania State House after the Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the beginning of the American Revolutionary War.[12] Congress adopted the Olive Branch Petition in July 1775, which affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain and entreated King George III to prevent further conflict.[13] The petition was rejected—in August 1775, the King's Proclamation of Rebellion formally declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion.[14]

In February 1776, colonists received news that Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels.[15] Although the measure amounted to a virtual declaration of war by the British,[16] Congress did not have immediate authority to declare independence until each individual colony authorized its delegates to vote for independence.[17] On June 11, Congress appointed the "Committee of Five," consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, to draft an official declaration of independence.[18] Congress unanimously adopted its final version of the Declaration on July 4, marking the formation of the United States of America.[19] Historians believe that the Old State House Bell, now known as the Liberty Bell, was one of the bells rung to mark the reading of the Declaration on July 8.[20]

Philadelphia Convention

After 1781, the national government operated under the Articles of Confederation, which gave the federal government virtually no power to regulate domestic affairs or raise revenue.[21] At the Annapolis Convention in September 1786, the delegates asked for a broader meeting to be held the next May in Philadelphia to address the regulation of trade and the structure of the government.[22] This resulted in the Philadelphia Convention, which met from May 14 to September 17, 1787 at the Pennsylvania State House.[23]

The Convention was dominated by controversies and conflicting interests, but the delegates forged a Constitution that has been called a "bundle of compromises".[24] At the convention, delegate James Madison presented the Virginia Plan, which proposed a national government with three branches with proportional representation.[25] Large states supported this plan, but smaller states feared losing substantial power under the plan. In response, William Paterson designed the New Jersey Plan, which proposed a one-house (unicameral) legislature in which each state, regardless of size, would have one vote, as under the Articles of Confederation.[26] Roger Sherman combined the two plans with the Connecticut Compromise, and his measure passed on July 16, 1787 by seven to six—a margin of one vote.[27] Other contentious issues were slavery and the federal regulation of commerce, which resulted in additional compromises.

Seat of the federal government

The Residence Act of 1790 empowered President George Washington to locate a permanent capital along the Potomac River. Robert Morris, a representative from Pennsylvania, convinced Congress to designate Philadelphia as the temporary capital city of the United States federal government.[28] From December 6, 1790 to May 14, 1800, the same block hosted federal, state, county, and city government offices.[29] Congress Hall, which was originally built to serve as the Philadelphia County Courthouse, served as the seat of the United States Congress.[30] The House of Representatives convened on the first floor and the Senate convened on the second floor. During Congress Hall's duration as the capitol of the United States, the country admitted three new states: Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee; ratified the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution; and oversaw the Presidential inaugurations of both George Washington (his second) and John Adams.[30] The President's House served as the official residence and principal workplace for President George Washington during his two terms, and President John Adams occupied it from March 1797 to May 1800.[31] At the house, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Alien and Sedition Acts were signed.[31] The Supreme Court met at Old City Hall, where Chief Justices John Jay, John Rutledge, and Oliver Ellsworth presided over eleven docketed cases.[32]

While plans for the permanent capital were being developed, Pennsylvania delegates continued to put forth effort to undermine the plan. The city began construction on a massive new Presidential palace on Ninth Street and an expansion to Congress Hall.[28] Regardless of these efforts, the federal government relocated from Philadelphia for the final time on May 14, 1800.

Usage as a municipal facility

Despite its crucial role in the nation's founding, the site served most of its useful life as a municipal facility after the federal government relocated to the District of Columbia.[33] The state government moved to Harrisburg in October 1812, and since there was little use for the Pennsylvania State House, the State of Pennsylvania considered selling it and dividing the State House Yard into building lots as early as 1802. The state came close to demolishing the hall in 1816.[34] By 1818, the buildings had become surplus state property and were purchased by the City of Philadelphia, which used them uneventfully until late in the nineteenth century when the city government moved into a new city hall.[33] In 1852, the Liberty Bell was removed from its steeple and put on public display within the "Declaration Chamber" of Independence Hall. Between 1885 and 1915, the Liberty Bell made seven trips by train to various expositions and celebrations until the city refused further requests.[35]

Park history

The district's importance had waned with the western movement of City Hall and other institutions, but it remained an active and occupied business center.[36] The first proposal for an Independence Hall park originated in 1915, when architects Albert Kelsey and D. Knickerbacker Boyd proposed clearing the half-block between Chestnut Street and Ludlow Street in front of Independence Hall.[33] Kelsey and Boyd were motivated by a desire to create a fitting setting for Independence Hall, lessen the fire hazard, reduce congestion, and beautify the entire district.[33] The idea for a park gained momentum in the 1920s and 1930s, with patriotic sentiment accompanying the American Sesqui-Centennial in 1926.[36] The commencement of World War II led to a heightened sense of patriotism and urgency toward the protection of national monuments.[33]

On June 28, 1948, Congress passed Public Law 795, H.R. 5053 to authorize the creation of Independence National Historical Park,[37] and it was formally established on July 4, 1956. On March 16, 1959, it incorporated the Old Philadelphia Customs House (Second Bank of the United States), which had been designated a national historic site on May 26, 1939. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. In 1973, the Pennsylvania legislature voted to transfer the three blocks that compose Independence Mall to the federal government. Independence Hall was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site on October 24, 1979.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons Northeast Region Office is in the U.S. Custom House.[38]

Management

The National Park Service, a federal agency within the Department of the Interior, is responsible for the park's maintenance and preservation. In the 2003 fiscal year, the National Park Service spent approximately US$30.7 million on the park. Personnel and benefit costs represented about 41 percent of expenditures, and non-recurring construction and investment projects represented about 25 percent of expenditures. The Independence Visitor Center is operated as a joint venture between Independence National Historical Park and the Independence Visitor Center Corporation, a nonprofit organization. The National Park Service employs 247 permanent employees and seven seasonal employees. The park's cultural resource management program protects the historic buildings, archaeological sites, and cultural landscapes within the park, and approximately 1.5 million artifacts within the park. In 2003, the park's major projects primarily addressed repair and rehabilitation of park buildings and grounds.[1]

Independence Hall

Most of INHP's buildings and land are contained within the broad plaza called Independence Mall, which is bookended by the National Constitution Center on the north, Independence Hall on the south, and Fifth and Sixth Streets on the east and west, respectively. The Mall was created in the 1950s[39] by city planner Ed Bacon to bring an open space to the heart of historic Philadelphia in front of Independence Hall. Most of the buildings that previously occupied the site of Independence Mall were late nineteenth-century buildings that replaced earlier buildings destroyed by fire in 1851 and 1855. Proponents of the mall thought these buildings were eyesores because of their contrast with the historic nature of the area.[40] As plans emerged, retailers on Market Street resisted, arguing that the demolition was out-of-scale with the comparatively small landmark at its southern end.[40]

By 1959, when the bulldozers finished work on Independence Mall, only the Free Quaker Meetinghouse remained. The building had been used as a warehouse for plumbing supplies before its restoration as part of the project.[41] In 1961, the building was moved 38 feet west and 8 feet south to its present location to allow for the widening of Fifth Street.[42]

To plan for the celebration of the United States Bicentennial in 1976, the NPS relocated the Liberty Bell from Independence Hall to the glass-enclosed Liberty Bell Pavilion, as the Independence Hall could not accommodate the millions expected to visit Philadelphia that year.

In 1997, the NPS announced a plan to redesign Independence Mall. As part of the plan, several new public buildings were constructed. The Independence Visitors Center was opened in November 2001, the National Constitution Center was opened in July 2003, and the Liberty Bell, which had been housed in a glass pavilion, was moved into the Liberty Bell Center in October 2003. Exhibits include coverage of slavery in US history and its abolition.[43][44]

At the corner of 6th and Market Street, a President's House memorial outlines the site of the former mansion and commemorates the slaves who worked there. The former building had been demolished in portions starting in 1835, and its remnants were removed during the creation of Independence Mall.

Independence Mall is bordered by the Philadelphia Mint, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the National Museum of American Jewish History, the James A. Byrne Courthouse (which houses the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania), and the main studio of WHYY-TV.

Other park sites

Features of Independence NHP include:

- American Philosophical Society Hall

- Bishop White House

- Carpenters' Hall

- Christ Church

- City Tavern

- Thomas Bond House

- Congress Hall

- Declaration House

- Dolley Todd House

- Franklin Court and Benjamin Franklin Museum

- First Bank of the United States

- Free Quaker Meeting House

- Independence Hall

- Independence Visitor Center

- Korean War Memorial

- Liberty Bell Center

- Merchants' Exchange Building

- Mikveh Israel Cemetery

- New Hall Military Museum

- Old City Hall, meeting place of the Supreme Court

- President's House (Philadelphia)

- Second Bank of the United States

- Washington Square and the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier

Other NPS sites associated with Independence NHP but not located within its boundaries include:

Footnotes

- Independence National Historical Park - Business Plan, National Park Service.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Vogel, Morris (1991). Cultural connections: museums and libraries of Philadelphia and the Delaware. Temple University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-87722-840-0. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- Dunbar, Richard (1999). Philadelphia. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 10. ISBN 978-88-8029-926-4. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- Fodor's (2005). Fodor's Philadelphia and the Pennsylvania Dutch Country (3rd ed.). Random House Digital. p. 8. ISBN 1-4000-1567-7. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- Greiff, Constance M. (1987). Independence: the creation of a national park. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8122-8047-4. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

...and at the park's centerpiece, Independence Hall.

- Independence Hall Archived 2011-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, Historic Philadelphia.

- Staib, Walter. City Tavern Cookbook: 200 Years of Classic Recipes from America's First Gourmet Restaurant, p. 5, Running Press, Philadelphia, London, 1999. ISBN 0-7624-0529-5.

- Staib, Walter. City Tavern Baking & Dessert Cookbook: 200 Years of Authentic American Recipes, pp. 9, 14, Running Press, Philadelphia, London, 2003. ISBN 0-7624-1554-1.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. pp. 348–349. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- The Second Continental Congress, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Berkin, Carol; Miller, Christopher; Cherny, Robert; Gormly, James; Egerton, Douglas; Woestman, Kelly (2010). Making America: A History of the United States. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-618-47139-3. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

For all intents and purposes, King George III declared war on his colonies before the colonies declared war on their king.

- Chapter 1: The Original Source of Sovereignty, Mutualist.Org.

- Dunnell, John Peter (2008). American Greatness. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4363-6931-2. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- Owensby, J. Jackson (2010). The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited). A-Argus Books. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-9846195-4-2. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- The Liberty Bell Archived 2015-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Independence Hall Association.

- The Constitutional Convention of 1787, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

- Bloom, Sol; Johnson, Lars (2001). The Story of the Constitution. Arlington Heights, IL: Christian Liberty Press. p. 40. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Bloom, Sol; Johnson, Lars (2001). The Story of the Constitution. Arlington Heights, IL: Christian Liberty Press. p. 46. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Bloom, Sol; Johnson, Lars (2001). The Story of the Constitution. Arlington Heights, IL: Christian Liberty Press. p. 55. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Bloom, Sol; Johnson, Lars (2001). The Story of the Constitution. Arlington Heights, IL: Christian Liberty Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Bloom, Sol; Johnson, Lars (2001). The Story of the Constitution. Arlington Heights, IL: Christian Liberty Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Connecticut Compromise Mural, United States Senate.

- Frequently Asked Questions, Independence Hall Association.

- Historic Highlights & Society Hill, Wiley Publishing.

- Congress Hall, Independence Hall Association.

- President's House, Independence Hall Association.

- Old City Hall, Independence Hall Association.

- Framing Independence Mall Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Frequently Asked Questions, Independence Hall Association.

- The Liberty Bell: A Symbol for "We the People", National Park Service. p. 12.

- Cook, Kathleen Kurtz (1989). The creation of Independence National Historical Park and Independence Mall. Philadelphia: Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania. OL 23291672M.

- Independence National Historical Park - Long-Range Interpretive Plan, National Park Service.

- "Northeast Regional Office." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on June 9, 2015. "U.S. CUSTOM HOUSE, 7TH FLOOR PHILADELPHIA, PA 19106"

- "Fact Sheet :: gophila.com - The Official Visitor Site for Greater Philadelphia". www.gophila.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- Mires, Charlene. Independence Hall in American Memory, 2002, p. 218.

- Dedication Stone of the Free Quaker Meeting House, ushistory.org.

- Meeting House, Free Quakers.

- Independence National Historical Park - Long-Range Interpretive Plan, National Park Service.

- The Liberty Bell Archived 2015-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, ushistory.org.

References

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Independence National Historical Park. |

- National Park Service: Independence National Historical Park

- Independence Hall: International Symbol of Freedom, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- The Liberty Bell: From Obscurity to Icon, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- NPS History E-Library, Independence NHP

- Map of Independence NHP area, NPS.gov (pdf)