Romani people in Romania

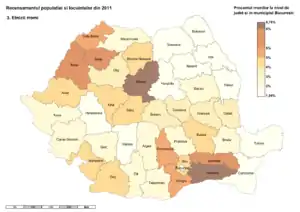

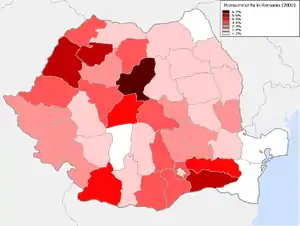

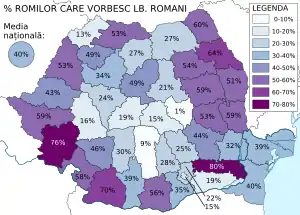

Romani people (Roma; Romi, traditionally Țigani, "Gypsies") constitute one of Romania's largest minorities. According to the 2011 census, their number was 621,000 people or 3.3% of the total population, being the second-largest ethnic minority in Romania after Hungarians.[1] There are different estimates about the size of the total population of people with Romani ancestry in Romania, varying from 4.6 percent to over 10 percent of the population, because many people of Romani descent do not declare themselves Roma.[2][3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 621,000[1] (2011 census) | |

| Languages | |

| Romani and other languages (Romanian, Hungarian | |

| Religion | |

|

Origins

The Romani people originate from northern India,[4][5][6][7][8][9] presumably from the northwestern Indian regions such as Rajasthan[8][9] and Punjab.[8]

The linguistic evidence has indisputably shown that roots of Romani language lie in India: the language has grammatical characteristics of Indian languages and shares with them a big part of the basic lexicon, for example, body parts or daily routines.[10] More exactly, Romani shares the basic lexicon with Hindi and Punjabi. It shares many phonetic features with Marwari, while its grammar is closest to Bengali.[11]

Genetic findings in 2012 suggest the Romani originated in northwestern India and migrated as a group.[5][6][12] According to a genetic study in 2012, the ancestors of present scheduled tribes and scheduled caste populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Ḍoma, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma.[13]

In February 2016, during the International Roma Conference, the Indian Minister of External Affairs stated that the people of the Roma community were children of India. The conference ended with a recommendation to the Government of India to recognize the Roma community spread across 30 countries as a part of the Indian diaspora.[14]

Terminology

In Romani, the native language of the Romani, the word for people is pronounced [ˈroma] or [ˈʀoma] depending on dialect ([ˈrom] or [ˈʀom] in the singular). Starting from the 1990s, the word has also been officially used in the Romanian language, although it has been used by Romani activists in Romania as far back as 1933.[15][16]

There are two spellings of the word in Romanian: rom (plural romi), and rrom (plural rromi). The first spelling is preferred by the majority of Romani NGOs[17] and it is the only spelling accepted in Romanian Academy's Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române.[18] The two forms reflect the fact that for some speakers of Romani there are two rhotic (ar-like) phonemes: /r/ and /ʀ/.[19] In the government-sponsored (Courthiade) writing system /ʀ/ is spelt rr. The final i in rromi is the Romanian (not Romani) plural.

The traditional and colloquial Romanian name for Romani, is "țigani" (cognate with Serbian cigani, Hungarian cigány, Greek ατσίγγανοι (atsinganoi), French tsiganes, Portuguese ciganos, Dutch zigeuner, German Zigeuner, Turkish Çigan, Persian زرگری (zargari), Arabic غجري (ghajri), Italian zingari, Russian цыгане (tsygane) and Kazakh Сыған/ســىــعــان (syǵan)). Depending on context, the term may be considered to be pejorative in Romania.[20]

In 2009–2010, a media campaign followed by a parliamentary initiative asked the Romanian Parliament to accept a proposal to revert the official name of country's Roma (adopted in 2000) to Țigan (Gypsy), the traditional and colloquial Romanian name for Romani, in order to avoid the possible confusion among the international community between the words Roma — which refers to the Romani ethnic minority — and Romania.[21] The Romanian government supported the move on the grounds that many countries in the European Union use a variation of the word Țigan to refer to their Gypsy populations. The Romanian upper house, Senate, rejected the proposal.[22][23]

History and integration

In combination with the Mongol invasion of Europe the first Romani had reached the territory of present-day Romania around the year 1241.[24] At the beginning of the 14th century, when the Mongols withdrew from Eastern Europe, the Romani who were left were taken as prisoners and slaves. According to documents signed by Prince Dan I the first captured Romani in Wallachia dates back to year 1385.

In fact, the Romani people, and the Romani language, have their origin in northern India. The presence of the Roms within the territory of present-day Romania dates back to the 14th century. The population of Roms fluctuated depending on diverse historical and political events.

Before 1856

Until their liberation on February 20, 1856, most Roms lived in slavery. They could not leave the property of their owners (the boyars and the orthodox monasteries). Around the year 1850, about 102,000 Romani lived in the Danubian Principalities, comprising 2.7% of the population (90,000 or 4.1% in Wallachia and 12,000 or 0.8% in Moldavia).[25]

Between 1856 and 1918

After their liberation in 1856, a significant number of Roms left Wallachia and Moldavia.

In 1886 the number of Roms was estimated at around 200,000, or 3.2% of Romania's population.[26] The 1899 census counted around 210,806 "others", of whom roughly half (or 2% of the country's population) were Romani.

In Bessarabia, annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812, the Roms were liberated in 1861. Many of them migrated to other regions of the Empire,[27] while important communities remained in Soroca, Otaci and the surroundings of Cetatea Albă, Chișinău, and Bălți.

Between 1918 and 1945

The 1918 union with Transylvania, Banat, Bukovina and Bessarabia increased the number of ethnic Romani in Romania.

The first census in interwar Romania took place in 1930; 242,656 persons (1.6%) were registered as Gypsies (țigani).

The territory lost in 1940 caused a drop in the number of Romani, leaving a high number especially in Southern Dobruja and Northern Transylvania.

During the Second World War, the Fascist regime of Ion Antonescu deported 25,000 Romani to Transnistria; of these, 11,000 died.[28] In all, from the territory of present-day Romania (including Northern Transylvania), 36,000 Romani perished during that time.[29]

During the communist regime and after 1989

The communist authorities have tried to integrate the Roma community, for example by building flats for them. Apart from the 1977 national campaign that confiscated all the gold (particularly jewelry) belonging to the Roma, there are few documents about the particular situation of this ethnic group during Ceaușescu's dictatorship.

.jpg.webp)

.jpeg.webp)

Sometimes the authorities tried to cover up crimes related to racial hatred, so as not to raise the social tension. An example of this is the crime committed by a truck driver named Eugen Grigore, from Iași who, in 1974, to avenge the death of his wife and his three children caused by a group of Roma, drove his truck into a Roma camp, killing 24 people. This fact was made public only in the 2000s.[30]

After the fall of communism in Romania, there were many inter-ethnic conflicts targeting the Roma community, the most famous being the 1993 Hădăreni riots. Other important clashes against Roma happened, from 1989 to 2011, in Turulung, Vârghiș, Cuza Vodă, Bolintin-Deal, Ogrezeni, Reghin, Cărpiniş, Găiseni, Plăieşii de Sus, Vălenii Lăpuşului, Racşa, Valea Largă, Apata, Sânmartin, Sâncrăieni and Racoş.[31] During the June 1990 Mineriad, a group of protesters organized a pogrom in the Roma neighborhoods of Bucharest. According to the press, the raids resulted in the destruction of apartments and houses, beatings of men and assaults of women of Roma ethnicity.[31] There have also often been many politicians who have made offensive statements against the Roma people, such as the president of that time Traian Băsescu, who, in 2007, called a Roma woman "stinky Gypsy".[32] In November 2011, the mayor of the city of Baia Mare, Cătălin Cherecheș, decided to build a wall in a neighborhood inhabited by a Roma community. The national anti-discrimination council in 2020 fined him for not demolishing the wall.[33]

A 2000 EU report about Romani said that in Romania… the continued high levels of discrimination are a serious concern.. and progress has been limited to programmes aimed at improving access to education.[34]

Various international institutions, such as the World Bank, the Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), and the Open Society Institute (OSI) launched the 2005-2015 Decade for Roma Inclusion.[35] To this, followed the EU Decade of Roma Inclusion [36] to combat this and other problems. The integration of the Roma is made difficult also due to a great economic and social disparity; according to the 2002 census, Roma are the ethnic group with the highest percentage of illiteracy (25,6%), with only the Turkish minority having a similarly high percentage (23,7%).[37] Within the Romanian education system there is discrimination and segregation, which leads to higher drop-out rates and lower qualifications for the Romani students.[38] The life expectancy of the Romani minority is also 10 years lower than the Romanian average.[38]

The accession of Romania to the European Union in 2007 led many members of the Romani minority, the most socially disadvantaged ethnic group in Romania, to migrate en masse to various Western European countries (mostly to Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Belgium, United Kingdom, Sweden) hoping to find a better life. The exact number of emigrants is unknown. In 2007 Florin Cioabă, an important leader of the Romani community (also known as the "King of all Gypsies") declared in an interview that he worried that Romania may lose its Romani minority.[39] However, the next population census in 2011 showed a substantial rise in those recording Romani ethnicity.[1]

The Pro Democrația association in Romania revealed that 94% of the questioned persons believe that the Romanian citizenship should be revoked to the ethnic Roms who commit crimes abroad.[40] Another survey revealed that 68% of Romanians think that Roma people commit most crimes, 46% think that they are thieves, while 43% lazy and dirty, and 36% believe that the Roma community might become a threat to Romania.[41]

In another survey made in 2013 by IRES, 57% respondents stated that they generally don't trust people of Roma ancestry and only 17% said to have a Roma friend.[42] Still, 57% said that this ethnic group is not discriminated in Romania, 59% claimed that the Roma should not receive help from the state, and that Roma people are poor because they don't like to work (72%) and that most of them are thugs (61%).[42]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1887 | 200,000 | — |

| 1930 | 262,501 | +31.3% |

| 1948 | 53,425 | −79.6% |

| 1956 | 104,216 | +95.1% |

| 1966 | 64,197 | −38.4% |

| 1977 | 227,398 | +254.2% |

| 1992 | 401,087 | +76.4% |

| 2002 | 535,140 | +33.4% |

| 2011 | 621,573 | +16.2% |

_Romania_2002.png.webp)

| County | Romani population (2011 census) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mureș | 46,947 | 8.52% |

| Călărași | 22,939 | 7.48% |

| Sălaj | 15,004 | 6.69% |

| Bihor | 34,640 | 6.02% |

| Giurgiu | 15,223 | 5.41% |

| Dâmbovița | 27,355 | 5.27% |

| Ialomița | 14,278 | 5.21% |

| Satu Mare | 17,388 | 5.05% |

| Dolj | 29,839 | 4.52% |

| Sibiu | 17,946 | 4.52% |

| Buzău | 20,376 | 4.51% |

| Alba | 14,292 | 4.17% |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | 11,937 | 4.17% |

| Mehedinți | 10,919 | 4.11% |

| Ilfov | 15,634 | 4.02% |

| Covasna | 8,267 | 3.93% |

| Arad | 16,475 | 3.83% |

| Vrancea | 11,966 | 3.52% |

| Brașov | 18,519 | 3.37% |

| Cluj | 22,531 | 3.26% |

| Galați | 16,990 | 3.17% |

| Argeș | 16,476 | 2.69% |

| Brăila | 8,555 | 2.66% |

| Maramureș | 12,211 | 2.55% |

| Bacău | 15,284 | 2.48% |

| Prahova | 17,763 | 2.33% |

| Olt | 9,504 | 2.18% |

| Teleorman | 8,198 | 2.16% |

| Timiș | 14,525 | 2.12% |

| Gorj | 6,698 | 1.96% |

| Suceava | 12,178 | 1.92% |

| Vâlcea | 6,939 | 1.87% |

| Hunedoara | 7,475 | 1.79% |

| Harghita | 5,326 | 1.71% |

| Caraș-Severin | 7,272 | 1.70% |

| Tulcea | 3,423 | 1.61% |

| Vaslui | 5,913 | 1.50% |

| Iași | 11,288 | 1.46% |

| Neamț | 6,398 | 1.36% |

| Bucharest | 23,973 | 1.27% |

| Constanța | 8,554 | 1.25% |

| Botoșani | 4,155 | 1.01% |

| Total[43] | 621,573 | 3.09 % |

Religion

According to the 2002 census, 81.9% of Roma are Orthodox Christians, 6.4% Pentecostals, 3.8% Roman Catholics, 3% Reformed, 1.1% Greek Catholics, 0.9% Baptists, 0.8% Seventh-Day Adventists, while the rest belong to other religions such as (Islam and Lutheranism).[44]

Cultural influence

Notable Romanian Romani musicians and bands include Grigoraş Dinicu, Johnny Răducanu, Ion Voicu, Taraf de Haïdouks and Connect-R.

The musical genre manele, a part of Romanian pop culture, is often sung by Romani singers in Romania and has been influenced in part by Romani music, but mostly by Oriental music brought in Romania from Turkey during the 19th century. Romanian public opinion about the subject varies from support to outright condemnation.

Self-proclaimed "Romani royalty"

The Romani community has:

- An "Emperor of Roma from Everywhere", as Iulian Rădulescu proclaimed himself.[45] In 1997, Iulian Rădulescu announced the creation of Cem Romengo – the first Rom state in Târgu Jiu, in southwest Romania. According to Rădulescu, "this state has a symbolic value and does not affect the sovereignty and unity of Romania. It does not have armed forces and does not have borders". According to the 2002 population census, in Târgu Jiu there are 96.79% Romanians (93,546 people), 3.01% (Romani) (2,916 people) and 0.20% others.[46]

- A "King of Roma". In 1992, Ioan Cioabă proclaimed himself King of Roma at Horezu, "in front of more than 10,000 Rroms" (according to his son's declaration). His son, Florin Cioabă, succeeded him as king.[47]

- An "International King of Roma". On August 31, 2003, according to a decree issued by Emperor Iulian, Ilie Stănescu was proclaimed king. The ceremony took place in Curtea de Argeş Cathedral, the Orthodox Church where Romania's Hohenzollern monarchs were crowned and are buried. Ilie Stănescu died in December, 2007.[48]

Image gallery

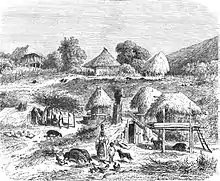

A șatră or village peopled by members of the Romani community of Romania

A șatră or village peopled by members of the Romani community of Romania Purported bulibașa (head of a Romani community)

Purported bulibașa (head of a Romani community) Romanian president Traian Băsescu (left) at a meeting with the representatives of the Romani minority organizations (right)

Romanian president Traian Băsescu (left) at a meeting with the representatives of the Romani minority organizations (right) Type of houses owned by wealthy Romani families

Type of houses owned by wealthy Romani families Nazi era image. Posed photo of some NSDAP leaders in 1941, with Romani flower sellers.

Nazi era image. Posed photo of some NSDAP leaders in 1941, with Romani flower sellers. Gábor Hungarian speaking gypsies from Transylvania

Gábor Hungarian speaking gypsies from Transylvania

Notable people

- Sandu Ciorba, singer

- Grigoraş Dinicu, violinist

- Damian Draghici, nai player

- Ştefan Bănică, Sr., singer

- Ştefan Bănică, Jr., singer

- Fănică Luca, player of the nai

- Bănel Nicoliţă, footballer

- Alexandru Neagu, footballer

- Johnny Răducanu, jazz musician

- Adrian Copilul Minune, manele singer

- Ion Voicu, classical violinist and conductor

- Mădălin Voicu, conductor

- Nicolae Guţă, manele singer

- Marcel Pavel, singer

- Fărâmiţă Lambru, singer

- Anca Parghel, jazz singer

- Connect-R, singer

See also

- National Agency for the Roma, an agency of the Romanian government dealing with Roma affairs

- Slavery in Romania

- List of towns in Romania by Romani population

- Antiziganism

- 2006 Ferentari riot

References

- "Romanian 2011 census" (PDF) (in Romanian). www.edrc.ro. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- Margaret Beissinger, Speranta Radulescu, Anca Giurchescu, Manele in Romania: Cultural Expression and Social Meaning in Balkan Popular Music, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, p. 33, ISBN 9781442267084

- Holly Cartner, Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Persecution of Gypsies in Romania, a Helsinki Watch Report Human Rights Watch, 1991, p. 5, ISBN 9781564320377

- Hancock, Ian F. (2005) [2002]. We are the Romani People. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8: ‘While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Romani groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European’

- Mendizabal, Isabel; et al. (6 December 2012). "Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. PMID 23219723.

- Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India". New York Times.

- Current Biology.

- Meira Goldberg, K.; Bennahum, Ninotchka Devorah; Hayes, Michelle Heffner (2015-09-28). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives - K. Meira Goldberg, Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum, Michelle Heffner Hayes. p. 50. ISBN 9780786494705. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- Dorian, Frederick; Duane, Orla; McConnachie, James (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. p. 147. ISBN 9781858286358. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- Šebková, Hana; Žlnayová, Edita (1998), Nástin mluvnice slovenské romštiny (pro pedagogické účely) (PDF), Ústí nad Labem: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity J. E. Purkyně v Ústí nad Labem, p. 4, ISBN 978-80-7044-205-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04

- Hübschmannová, Milena (1995). "Romaňi čhib – romština: Několik základních informací o romském jazyku". Bulletin Muzea Romské Kultury. Brno: Muzeum romské kultury (4/1995).

Zatímco romská lexika je bližší hindštině, marvárštině, pandžábštině atd., v gramatické sféře nacházíme mnoho shod s východoindickým jazykem, s bengálštinou.

- "5 Intriguing Facts About the Roma". Live Science.

- Rai, N; Chaubey, G; Tamang, R; Pathak, AK; Singh, VK; et al. (2012), "The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations", PLOS ONE, 7 (11): e48477, Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748477R, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048477, PMC 3509117, PMID 23209554

- "Can Romas be part of Indian diaspora?". khaleejtimes.com. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Ziua Activistului Rom, retrieved 2009-01-28

- Roma, Sinti, Gypsies, Travellers... at inotherwords-project.eu Archived July 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Minoritatea Roma – cea mai importanta minoritate din Europa. Romanes.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15. Archived May 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "rom". Dicţionarul explicativ al limbii române (in Romanian). Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică "Iorgu Iordan", Editura Univers Enciclopedic. 1988.

- Matras, Yaron (2005). Romani: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521023306.

- Discriminarea se invata in familie, archived from the original on 2011-07-19, retrieved 2009-01-28

- Propunere Jurnalul Naţional: "Ţigan" în loc de "rom" Archived 2014-07-12 at the Wayback Machine (in Romanian)

- Romania's Government Moves to Rename the Roma at time.com

- Romania Declines to Turn Roma Into 'Gypsies' at balkaninsight.com

- Achim, p.27-28

- Neueste Erdbeschreibung und Staatenkunde. Zweiter Band. von Dr. F.H.Ungewitter. Dresden, 1848

- Mayers Konversationslexikon, 1892. Retrobibliothek.de. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- Ion Nistor, Istoria Basarabiei, Humanitas, Bucuresti, 1991

- The report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania - The Deportation of the Roma and their treatment in Transnistria November 11, 2004 (PDF), from Jewish Virtual Library

- Society for Threatened Peoples. Gfbv.it (2004-02-25). Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- Ionuţ Benea (June 5, 2015). "Povestea şoferului care a ucis 24 de ţigani cu un camion. Securitatea a dosit măcelul, de frica conflictelor interetnice". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Gabriel Sala (February 25, 2017). "Conflicte interetnice în istoria recentă a României". Descoperă (in Romanian). Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Bogdana Boga (November 8, 2007). "Basescu a pierdut procesul "tiganca imputita"". Ziare.com (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Primarul din Baia Mare, amendat pentru că nu a demolat un zid în jurul unor blocuri de romi". Mediafax (in Romanian). January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "The Situation of Roma in an Enlarged European Union" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009.

- "Decade in Brief". Decade of Roma Inclusion. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015.

- "INSTRUMENT FOR PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE (IPA II) 2014-2020" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- "Populatia de 10 ani si peste analfabeta dupa etnie, pe sexe si judete" (PDF) (in Romanian). Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Delia-Luiza Niță, ENAR Shadow Report 2008: Racism in Romania, European Network Against Racism

- Regele Cioabă se plânge la Guvern că rămâne fără supuşi – Gandul Archived 2010-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Gandul.info (2007-09-10).Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- Evenimentul Zilei. April 7, 2010. Evz.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- V.M. (November 27, 2010). "Sondaj CCSB: 36% dintre romani cred ca tiganii ar putea deveni o amenintare pentru tara". Hotnews.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Vasile Dâncu. "Tele-vremea țiganilor" (PDF). IRES (in Romanian). Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Institutul Naţional de Statistică. 2011 http://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-2/. Retrieved 2020-10-06. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Census 2002, by religion. (PDF). insse.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- "Regele Cioabă vs. Iulian impăratul". Maxim (in Romanian). Archived from the original on December 8, 2006.

- Recensământ 2002 Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Recensamant.referinte.transindex.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- Popan, Cosmin (June 10, 2006). "Cioabă şi oalele sparte din şatră" (in Romanian).

- "La Mânăstirea Curtea de Argeş s-au sfinţit doar podoabele specifice rromilor". Curierul Naţional (in Romanian). September 3, 2003.

External links

- Assessment for Roma in Romania Center for International Development and Conflict Management Last Updated December 31, 2003

- Come Closer. Inclusion and Exclusion of Roma in Present Day Romanian Society By Gabor Fleck, Cosima Rughinis (Eds.) 2009 ISBN 978-973-8973-09-1. Full text from Google Books