Salah times

Salah times are prayer times when Muslims perform salah. The term is primarily used for the five daily prayers including the Friday prayer, which is normally Dhuhr prayer but on Fridays it is obligated to be prayed in a group. The salah times were taught by Allah to Muhammad.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Prayer times are standard for Muslims in the world, especially the fard prayer times. They depend on the condition of the Sun and geography. There are varying opinions regarding the exact salah times, the schools of Islamic thought differing in minor details. All schools of thought agree that any given prayer cannot be performed before its stipulated time.

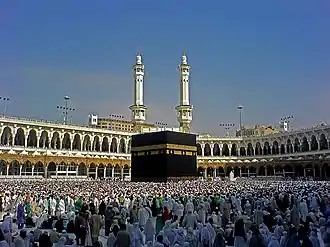

Muslims pray five times a day, with their prayers being known as Fajr (dawn), Dhuhr (after midday), Asr (afternoon), Maghrib (sunset), Isha (nighttime), facing towards Mecca.[1] The direction of prayer is called the qibla; the early Muslims initially prayed in the direction of Jerusalem before this was changed to Mecca in 624 CE, about a year after Muhammad's migration to Medina.[2][3]

The timing of the five prayers are fixed intervals defined by daily astronomical phenomena. For example, the Maghrib prayer can be performed at any time after sunset and before the disappearance of the red twilight from the west.[4] In a mosque, the muezzin broadcasts the call to prayer at the beginning of each interval. Because the start and end times for prayers are related to the solar diurnal motion, they vary throughout the year and depend on the local latitude and longitude when expressed in local time.[5][note 1] In modern times, various religious or scientific agencies in Muslim countries produce annual prayer timetables for each locality, and electronic clocks capable of calculating local prayer times have been created.[6] In the past, some mosques employed astronomers called the muwaqqits who were responsible for regulating the prayer time using mathematical astronomy.[5]

The five intervals were defined by Muslim authorities in the decades after the death of Muhammad in 632, based on the hadith (the reported sayings and actions) of the Islamic prophet.[4] The five fixed prayer times in Islamic prayer were likely influenced by the canonical hours of Jews and Christians, who prayed at seven set times a day; Muhammad and his companions had extensive contact with Syrian Christian monks.[3] Abu Bakr and other early followers of Muhammad were exposed to these fixed times of prayer of the Syrian Christians in Abyssinia and likely relayed their observations to Muhammad, "placing the potential for Christian influence directly within the Prophet’s circle of followers and leaders."[3]

Five daily prayers

The five daily prayers are obligatory (fard) and they are performed at times determined essentially by the position of the Sun in the sky. Hence, salat times vary at different locations on the Earth. Wudu is needed for all of the prayers.

Fajr (dawn)

Fajr begins at subh saadiq—true dawn or the beginning of twilight, when the morning light appears across the full width of the sky—and ends at sunrise.

Dhuhr (midday)

The time interval for offering the Zuhr or Dhuhr salah timing starts after the sun passes its zenith and lasts until 20 min (approx) before the call for the Asr prayer is to be given. There is thus a long period of time within which this prayer can be offered, but people usually make their prayer within two hours after the Azan has been announced from Mosque. This prayer needs to be given in the middle of the work-day, and people normally make their prayers during their lunch break.

Shia differs regarding end of zuhr time. Per all major Jafari jurists, end of dhuhr time is about 10 minutes before sunset, the time that belongs exclusively to asr prayer. Dhuhr and asr time overlaps, apart from first 5 minutes of dhuhr, which is exclusively delegated for it. Asr prayer cannot be offered before zuhr in the zuhr time.

Asr (afternoon)

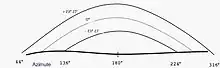

The Asr prayer starts when the shadow of an object is the same length as the object itself (or, according to Hanafi school, twice its length) plus the shadow length at zuhr, and lasts till sunset. Asr can be split into two sections; the preferred time is before the sun starts to turn orange, while the time of necessity is from when the sun turns orange until sunset.

Shia (Jafari madhab) differs regarding start of asr time. Per all major Jafari jusrists, start of asr time is about 5 minutes after the time of sun passing through zenith, that time belongs exclusively to dhuhr prayer. Time for dhuhr and asr prayers overlap, but the zuhr prayer must be offered before asr, except the time about 10 minutes before sunset, which is delegated exclusively to asr. In the case that the mentioned time is reached, asr prayer should be offered first (ada - on time) and dhuhr (kada - make up, late) prayer should be offered after asr.

Maghrib (sunset)

The Maghrib prayer begins when the sun sets, and lasts until the red light has left the sky in the west.

Isha (night)

The Isha'a or isha prayer starts when the red light is gone from the western sky, and lasts until the rise of the "white light" (fajr sadiq) in the east. The preferred time for Isha is before midnight, meaning halfway between sunset and sunrise.

Time calculation

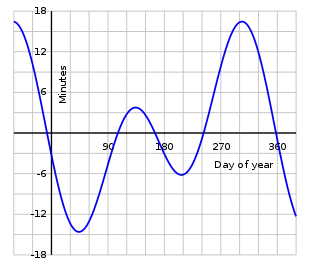

To calculate prayer times two astronomical measures are necessary, the declination of the sun and the difference between clock time and sundial clock. This difference being the result of the eccentricity of the earth's orbit and the inclination of its axis, it is called the Equation of time. The declination of the sun is the angle between sun's rays and the equator plan.[7]

In addition to the above measures, to calculate prayer times for a specific location we need its spherical coordinates.[8]

In the following is the time zone, and the time equation value. and are the Longitude and the Latitude of the considered point, respectively. denotes the Declination of the Sun for a given date.

Another important equation gives the time difference between when the sun hits its highest point in the sky (Dhuhr time) and any other angle , as follow:

- Midday (Dhuhr) time is easily obtained. When the sun reaches the mid sky, time is given by:

- Sunrise (Chorok) and Sunset (Maghreb) time are given by , in fact it is the astronomical sunset/sunrise that occurs for . 0.833 is a slight correction that gives the actual time. So and .

If we consider the elevation of the point we should add another correction to the constant .

- For Fajr and Isha many conventions about the angle exist. It is of 17 and 18 degrees respectively for Fadjr and Isha prayers according to the Muslim World League.

- For Asr time according to the majority of Muslim schools including Shafi'i, Maliki, Hanbali, and Ja'fari, it is when the length of an object shadows became equal to its length plus the length of its shadow at noon. The Hanafi schools states that the time of Asr is when an object's shadow reaches two times the length of the object itself, plus the length of its shadow at noon. The time the shadow of an object reaches times its length is given by the equation: .

- It is called for the Maghrib prayer when the sun is completely folded behind the horizon, plus 3 minutes by precaution.

Technological advances have allowed for products such as software-enhanced azan clocks that use a combination of GPS and microchips to calculate these formulas. This allows Muslims to live further away from mosques than previously possible, as they no longer need to rely solely on a muezzin in order to keep an accurate prayer schedule.[9]

Friday prayer

The Friday prayer replaces the dhuhr prayer performed on the other six days of the week. The precise time for this congregational prayer varies with the mosque, but in all cases it must be performed after dhuhr and before asr times. If one is unable to join the congregation, then they must pray the dhuhr prayer instead. This salat is compulsory to be done with ja'maat for men. Women have the option to perform Jumm'ah in the mosque or to pray zuhr.

Other salat

Eid prayers

Eid-ul-Adhaa and Eid-ul-Fitr

Taraweeh

Also known as Salat Qiyam Allayl,[10] this Salat is considered a Nafilah (Arabic: صلاة نفل; meaning: Voluntary/Optional Salah (formal worship)) and is performed during the month of Ramadan. The prayer is performed after Isha (night) prayer, in congregation. 20 Rakaat are typically performed; a short rest is taken after every four Rakaats. Word Taraweeh comes from tarviha, which means one time rahat (rest); the two time rahat (rest) is known as tarvihatain, which comes to eight Rakaats; the three or more times rahat is called taraveh as it comes to 12 or more Rakaats.

Salatul Janazah

Salat-e-Janaza or Namaze Janaza (Funeral prayer)

The Muslims of the community gather to offer their collective prayers for forgiveness for the dead. This prayer has been generally termed as the Namaze Janaza. The prayer is offered in a particular way with extra (four) Takbirs but there is no Ruku' (bowing) and Sajdah (prostrating). It becomes obligatory for every Muslim adult male to perform the funeral prayer upon the death of any Muslim, however when it is performed by the few it will not be obligation for all. Women also can attend the prayer.

Salatul Istisqa

This Salat is considered a Nafilah for seeking rain water from God.

See also

Notes

- For the day-to-day variation of the prayer times, see, for example, a prayer timetable for Banyuasin, Indonesia, for the month of Ramadan in 2012.

References

- Samovar, Larry A.; Porter, Richard E.; McDaniel, Edwin R. (2008). Intercultural Communication: A Reader: A Reader. Cengage Learning. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-495-55418-9.

- Wensinck, Arent Jan (1986). "Ḳibla: Ritual and Legal Aspects". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Heinz, Justin Paul (2008). The Origins of Muslim Prayer: Sixth and Seventh Century Religious Influences on the Salat Ritual. University of Missouri-Columbia. pp. 115, 123, 125, 133, 141–142.

- Wensinck, Arent Jan (1993). "Mīḳāt: Legal aspects". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- King, David A. (1996). "On the role of the muezzin and the muwaqqit in medieval Islamic society". In E. Jamil Ragep; Sally P. Ragep (eds.). Tradition, Transmission, Transformation. E.J. Brill. pp. 285–345. ISBN 90-04-10119-5.

- King, David A. (1993). "Mīḳāt: Astronomical aspects". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 27–32. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Approximate Solar Coordinates

- Calculating Prayer Times

- Gorman, Carma R. (2009). "Religion on Demand: Faith-based Design". Design and Culture. 1 (1).

- "Qiyam". IslamQA. IslamQA. Retrieved 28 June 2015.