Television licence

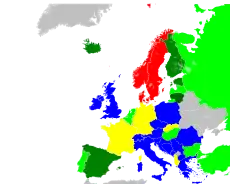

A television licence or broadcast receiving licence is a payment required in many countries for the reception of television broadcasts, or the possession of a television set where some broadcasts are funded in full or in part by the licence fee paid. The fee is sometimes also required to own a radio or receive radio broadcasts. A TV licence is therefore effectively a hypothecated tax for the purpose of funding public broadcasting, thus allowing public broadcasters to transmit television programmes without, or with only supplemental, funding from radio and television advertisements. However, in some cases the balance between public funding and advertisements is the opposite – the Polish TVP broadcaster receives more funds from advertisements than from its TV tax.[1]

|

Television licence only

Television licence and advertising

Television licence, advertising and government grants

Government grants, and advertising

Commercial only

Government grants only

Unknown |

History

The early days of broadcasting presented broadcasters with the problem of how to raise funding for their services. Some countries adopted the advertising model, but many others adopted a compulsory public subscription model, with the subscription coming in the form of a broadcast licence paid by households owning a radio set (and later, a TV set).

The UK was the first country to adopt the compulsory public subscription model with the licence fee money going to the BBC, which was formed on 1 January 1927 by royal charter to produce publicly funded programming yet remain independent from government, both managerially and financially. The licence was originally known as a wireless licence.

With the arrival of television, some countries created a separate additional television licence, while others simply increased the radio licence fee to cover the additional cost of TV broadcasting, changing the licence's name from "radio licence" to "TV licence" or "receiver licence". Today most countries fund public radio broadcasting from the same licence fee that is used for television, although a few still have separate radio licences, or apply a lower or no fee at all for consumers who only have a radio. Some countries also have different fees for users with colour or monochrome TV. Many give discounts, or charge no fee, for elderly and/or disabled consumers.

Faced with the problem of licence fee "evasion", some countries choose to fund public broadcasters directly from taxation or via other less avoidable methods such as a co-payment with electricity billing. National public broadcasters in some countries also carry supplemental advertising.

The Council of Europe created the European Convention on Transfrontier Television in 1989 that regulates among other things advertising standards, time and the format of breaks, which also has an indirect effect on the usage of licensing. In 1993, this treaty entered into force when it achieved seven ratifications including five EU member states. It has since been acceded to by 34 countries, as of 2010.[2]

Television licences around the world

The Museum of Broadcast Communications in Chicago[3] notes that two-thirds of the countries in Europe and half of the countries in Asia and Africa use television licences to fund public television. TV licensing is rare in the Americas, largely being confined to French overseas departments and British Overseas Territories.

In some countries, radio channels and broadcasters' web sites are also funded by a radio receiver licence, giving access to radio and web services free of commercial advertising.

The actual cost and implementation of the television licence varies greatly from country to country. Below is a listing of the licence fee in various countries around the world.

| Country | Price | € equiv. per annum |

|---|---|---|

| 800 L | €5.81 | |

| TV – €251.16 to €320.76. Radio – €70.80 to €90.00.[4] | €335.14 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| Abolished. Flemish region and Brussels – 2001, Walloon region – 1 January 2018.[5] | €0 | |

| €46.00 | €46.00 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| Up to €137 | €137.00 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| 1620 Kč | €65.94 | |

| 1927 DKK (2020) | €259 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| Abolished[6] | €0 | |

| €139.00 | €139.00 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| €17.50 per month (payable per quarter, semi-annual or annual) | €210.00 | |

| €36 fee on electricity bills | €0 | |

| Abolished[7] | €0 | |

| Abolished[8] | €0 | |

| €160.00 | €160.00 | |

| Car owners pay €41 radio fee | €0 | |

| €90 fee on electricity bills | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| N/A | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| €3.50 per month | €42.00 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| Abolished | €0 | |

| Abolished, now a compulsory income related tax, up to Kr1700 per person | €10 to €170 per person | |

| TV (inc. radio) – 272.40 zł Radio – 84.00 zł | €60.24 | |

| €36.24 fee on electricity bills | €0 | |

| Abolished. | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| N/A | €0 | |

| fee on electricity bills | €0 | |

| €4.64 per month | €55.68 | |

| €153 | €153.00, Radio – €45.24 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| Abolished.[9] | €0 | |

| CHF 365.00 | €321.82 | |

| 2% of electricity bill and indirect charge on appliance at purchase | €0 | |

| None exists | €0 | |

| £157.50 colour / £53.00 monochrome | €179.90[10] |

Albania

The Albanian licence fee is 100 lekë (€0.80) per month, paid in the electricity bill.[11] However, the licence fee makes up only a small part of public broadcaster RTSH's funding. RTSH is mainly funded directly from the government through taxes (58%), the remaining 42% comes from commercials and the licence fee.

Austria

Under the Austria RGG (TV and Radio Licence Law), all broadcasting reception equipment in use or operational at a given location must be registered. The location of the equipment is taken to be places of residence or any other premises with a uniform purpose of use.

The agency responsible for licence administration in Austria is GIS - Gebühren Info Service GmbH, a 100% subsidiary of the Austrian Broadcasting Company (ORF), as well as an agency of the Ministry of Finance, charged with performing functions concerning national interests. Transaction volume in 2007 amounted to €682 million, 66% of which are allocated to the ORF for financing the organization and its programs, and 35% are allocated to the federal government and the local governments (taxes and funding of local cultural activities). GIS employs some 191 people and approximately 125 freelancers in field service. 3.4 million Austrian households are registered with GIS. The percentage of licence evaders in Austria amounts to 2.5%.

The main principle of GIS's communication strategy is to inform instead of control. To achieve this goal GIS uses a four-channel communication strategy:

- Above-the-line activities (advertising campaigns in printed media, radio and TV).

- Direct Mail.

- Distribution channels – outlets where people can acquire the necessary forms for registering (post offices, banks, tobacconists & five GIS Service Centers throughout Austria).

- Field service – customer consultants visiting households not yet registered.

The annual television & radio licence varies in price depending on which state one lives in. Annual fees from April 2017 are:[12]

| State | Television | Radio |

|---|---|---|

| Burgenland | €284.36 | €79.20 |

| Carinthia | €312.46 | €87.60 |

| Lower Austria | €315.96 | €87.60 |

| Upper Austria | €251.16 | €70.80 |

| Salzburg | €307.56 | €90.00 |

| Styria | €320.76 | €88.80 |

| Tyrol | €295.56 | €82.80 |

| Vorarlberg | €251.16 | €70.80 |

| Vienna | €315.96 | €87.96 |

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The licence fee in Bosnia and Herzegovina is around €46 per year.[13] The war and the associated collapse of infrastructure caused very high evasion rates. This has in part been resolved by collecting the licence fee as part of a household's monthly telephone bill. The licence fee is divided between three broadcasters:

- 50% for BHRT – (Radio and Television of Bosnia and Herzegovina) as main state level radio and television broadcaster in Bosnia and Herzegovina (also the only member of the EBU).

- 25% for RTVFBiH – (Radio-Television of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) radio and television broadcaster that primarily serves the population in the Federation of BiH entity

- 25% for RTRS – (Radio-Television of the Republika Srpska) radio and television broadcaster which primarily serves the population of Republika Srpska entity.

There is a public corporation in the establishment which should be consisted of all public broadcasters in BiH.

Croatia

The licence fee in Croatia is regulated with the Croatian Radiotelevision Act.[14][15] As of 2010, the last incarnation of the act dates from 2003.

The licence fee is charged to all owners of equipment capable of receiving TV and radio broadcasts. The total yearly amount of the fee is set each year as a percentage of the average net salary in the previous year, currently equal to 1.5%.[14] This works out at about €137 per year per household with at least one radio or TV receiver.

The fee is the main source of revenue for the national broadcaster Hrvatska Radiotelevizija (HRT), and a secondary source of income for other national and local broadcasters, which receive a minority share of this money. The Statute of the Croatian Radiotelevision[16] further divides their majority share to 66% for television and 34% for the radio, and sets out further financial rules.

According to law, advertisements and several other sources of income are allowed to HRT. However, the percentage of air time which may be devoted to advertising is limited by law to 9% per hour and is lower than the one that applies to commercial broadcasters. In addition, other rules govern advertising on HRT, including a limit on a single commercial during short breaks, no breaks during films, etc.

Croatian television law was formed in compliance with the European Convention on Transfrontier Television that Croatia had joined between 1999 and 2002.[2]

Czech Republic

The licence fee in the Czech Republic is 135 Kč (€4.992 [using exchange rate 27 July 2015]) per month as from 1 January 2008.[17] This increase is to compensate for the abolition of paid advertisements except in narrowly defined circumstances during a transitional period. Each household that owns at least one TV set pays for one TV licence or radio licence regardless of how many televisions and radios they own. Corporations and the self-employed must pay for a licence for each television and radio.

Denmark

The media licence fee in Denmark, as of 2020, is 1353 kr (€182).[18] This fee applies to all TVs, computers with Internet access or with TV tuners, or other devices that can receive broadcast TV, which means that you have to pay the TV licence if you have a relatively new mobile phone.[19] The black/white TV rate is no longer offered after 1 January 2007. The majority of the licence fee is used to fund the national radio and TV broadcaster DR. However, a proportion is used to fund TV 2's regional services.[20] TV2 itself used to get means from the licence fee but is now funded exclusively through advertising revenue.[21] Though economically independent from the licence fee TV2 still has obligations and requirements towards serving the public which are laid down in a so-called "public service contract" between the government and all public service providers. TV2 commercials may only be broadcast between programmes, including films. TV2 receives indirect subsidies through favourable loans from the state of Denmark. TV2 also gets a smaller part of the licence for their 8 regional TV-stations which have half an hour of the daily prime time of the channel (commercial-free) and may request additional time on a special new regional TV-channel. (This regional channel has several other non-commercial broadcasters apart from the TV2-regional programmes)

In 2018, the government of Denmark decided to "abolish" the fee from 2019.[22] In reality what happens is, the license fee will instead be paid over the tax bill.

France

In 2020, the television licence fee in France (mainland and Corsica) was €138 and in the overseas departments and collectivities it was €88.[23] The licence funds services provided by Radio France, France Télévisions and Radio France Internationale. Metropolitan France receives France 2, France 3, France 5, Arte, France 4 and France Ô, while overseas departments receive Outre-Mer 1ère also and France Ô, in addition to the metropolitan channels, now available through the expansion of the TNT service.[24] Public broadcasters in France supplement their licence fee income with revenue from advertising, but changes in the law in 2009 designed to stop public television chasing ratings, have stopped public broadcasters from airing advertising after 8 pm.[25] Between 1998 and 2004 the proportion of France Télévision's income that came from advertising declined from around 40% to 30%.[26] To keep the cost of collection low, the licence fee in France is collected as part of local taxes.[26] People who don’t own a TV can opt out in their tax declaration form [27]

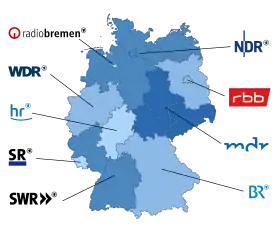

Germany

The licence fee in Germany is now a blanket contribution of €17.50 per month (€210 per annum) for all apartments, secondary residences, holiday homes as well as summer houses and is payable regardless of equipment or television/radio usage.[28] Businesses and institutions must also contribute (the amount is based on several factors including number of employees, vehicles and, for hotels, number of beds).[29] The fee is billed monthly but typically paid quarterly (yearly advanced payments are possible). It is collected by a public collection agency called Beitragsservice von ARD, ZDF und Deutschlandradio which is sometimes criticized for its measures.[30] Since 2013 only recipients of a certain kind of social benefit such as Arbeitslosengeld II or student loans and grants are exempt from the licence fee and those with certain disabilities can apply to pay a reduced contribution of €5.83. Low incomes in general like those of freelancers, trainees and the receipt of full unemployment benefit (Arbeitslosengeld I) are no longer reason for an exemption.[31]

Prior to 2013, only households and businesses with at least one television were required to pay. Households with no televisions but with a radio or an Internet-capable device were subject to a reduced radio-only fee.

The licence fee is used to fund the public broadcasters ZDF and Deutschlandradio as well as the nine regional broadcasters of the ARD network, who altogether run 22 television channels (10 regional, 10 national, 2 international: Arte and 3sat) and 61 radio stations (58 regional, 3 national). Two national television stations and 32 regional radio stations carry limited advertising. The 14 regional regulatory authorities for the private broadcasters are also funded by the licence fee (and not by government grants), and in some states, non-profit community radio stations also get small amounts of the licence fee. In contrast to ARD, ZDF and Deutschlandradio, Germany's international broadcaster Deutsche Welle is fully funded by the German federal government, though much of its new content is provided by the ARD.

Germany currently has one of the largest total public broadcast budgets in the world. The per capita budget is close to the European average. Annual income from licence fees reached more than €7.9 billion in 2016.[32]

The board of public broadcasters sued the German states for interference with their budgeting process, and on 11 September 2007, the Supreme Court decided in their favour. This effectively rendered the public broadcasters independent and self-governing.

Public broadcasters have announced that they are determined to use all available ways to reach their "customers" and as such have started a very broad Internet presence with media portals, news and TV programs. National broadcasters have abandoned an earlier pledge to restrict their online activities. This resulted in newspapers taking court action against the ARD, claiming that the ARD's Tagessschau smartphone app, that provides news stories at no cost to the app user, was unfairly subsidised by the licence fee, to the detriment of free-market providers of news content apps. The case was dismissed with the court advising the two sides to agree on a compromise.

Ghana

The licence fee in Ghana is used to fund the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC). It was reintroduced in 2015. TV users have to pay between GH¢36 and GH¢60 per year for using one or more TVs at home. [33]

Greece

The licence fee in Greece is indirect but obligatory and paid through electricity bills. The amount to be paid is €51.60 (2013) for every separate account of the electrical company (including residence, offices, shops and other places provided with electricity). Its beneficiary is the state broadcaster Ellinikí Radiofonía Tileórasi (ERT). Predicted 2006 annual revenue of ERT from the licence fee (officially called "retributive" fee) is €262.6 million (from €214.3 million in 2005).[34]

There has been some discussion about imposing a direct licence fee after complaints from people who do not own a television set and yet are still forced to fund ERT. An often-quoted joke is that even the dead pay the licence fee (since graveyards pay electricity bills).[35]

In June 2013, ERT was closed down to save money for the Greek government. In the government decree, it was announced during that time, licence fees are to be temporary suspended.[36] In June 2015, ERT was reopened, and licence holders are currently paying €36 per year.

Ireland

As of 2020, the current cost of a television licence in Ireland is €160.[37] However the licence is free to anyone over the age of 70 (regardless of means or circumstances), to some over 66, and to the blind (although these licences are in fact paid for by the state). The Irish post office, An Post, is responsible for collection of the licence fee and commencement of prosecution proceedings in cases of non-payment. However, An Post has signalled its intention to withdraw from the licence fee collection business.[38] The Irish TV licence makes up 50% of the revenue of RTÉ, the national broadcaster. The rest comes from RTÉ broadcasting advertisements on its radio and TV stations.[39] Furthermore, some RTÉ services, such as RTÉ 2fm, RTÉ Aertel, RTÉ.ie, and the transmission network operate on an entirely commercial basis.

The licence fee does not entirely go to RTÉ. After collection costs, 5% is used for the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland's "Sound and Vision Scheme", which provides a fund for programme production and restoration of archive material which is open to applications from any quarters. 5% of what RTÉ then receive is granted to TG4, as well as a requirement to provide them with programming. The remainder of TG4's funding is direct state grants and commercial income.

The licence applies to particular premises, so a separate licence is required for holiday homes or motor vehicles which contain a television.[40] The licence must be paid for premises that have any equipment that can potentially decode TV signals, even those that are not RTÉ's.

Italy

In 2014, the licence fee in Italy was €113.50 per household with a TV set, independent of use.[41] There is also a special licence fee paid by owners of one or more TV or radio sets on public premises or anyhow outside the household context, independent of the use. In 2016 the government opted to lower the licence fee to 100 euros per household and work it into the electricity bill in an attempt to eliminate evasion.[42][43] The fee is now (2018) 90 Euro.[44]

It is two-thirds of income for RAI (coming down from about half of income about seven years ago), which also broadcasts advertising, in 2014 giving about one-quarter of income.[45]

Japan

In Japan, the annual licence fee (Japanese: 受信料, jushin-ryō, "receiving fee") for terrestrial television broadcasts is ¥14,205 (slightly less if paid by direct debit) and ¥24,740 for those receiving satellite broadcasts.[46] There is a separate licence for monochrome TV, and fees are slightly less in Okinawa. The Japanese licence fee pays for the national broadcaster, Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai (NHK).

While every household in Japan with a television set is required to have a licence, it was reported in 2006 that "non-payment [had] become an epidemic" because of a series of scandals involving NHK.[47] As reported in 2005, "there is no fine or any other form of sanction for non-payment".[48]

Mauritius

The licence fee in Mauritius is Rs 1,200 per year (around €29).[49] It is collected as part of the electricity bill. The proceeds of the licence fee are used to fund the Mauritius Broadcasting Corporation (MBC). The licence fee makes up 60% of MBC's funding with most of the rest coming from television and radio commercials.[50] However, the introduction of private broadcasting in 2002 has put pressure on MBC's revenue from commercials and this is decreasing. Furthermore, MBC is affecting the profitability of the private stations who want the government to make MBC commercial free[49]

Montenegro

Under the Broadcasting Law (December 2002), every household and legal entity, situated in Montenegro, where technical conditions for reception of at least one radio or television programme have been provided, is obliged to pay a monthly broadcasting subscription fee. The monthly fee is €3.50.

The Broadcasting Agency of Montenegro is in charge of collecting the fee (currently through the telephone bills, but after the privatization of state-owned Telekom, the new owners, T-com, announced that they will not administer the collection of the fee from July 2007).

The funds from the subscription received by the broadcasting agency belong to:

- the republic's public broadcasting services (radio and television) – 75%

- the agency's fund for the support of the local public broadcasting services (radio and television) – 10%

- the agency's fund for the support of the commercial broadcasting services (radio and television) – 10%

- the agency – 5%

Namibia

The licence fee in Namibia was N$204 (about €23) in 2001.[51] The fee is used to fund the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC).[52]

Pakistan

The television licence in Pakistan is Rs 1200 per year. It is collected as a Rs 100 per month charge to all consumers of electricity.[53] The proceeds of the fee and advertising are used to fund PTV.

Poland

As of 2020, the licence fee in Poland for television set is 22.70 zł per month or 245.15 zł per year. The licence may be paid monthly, bi-monthly, quarterly, half-yearly or annually, but the total cost when paying for less than a year in advance is higher (up to 10%). Those that have no TV but have a radio must pay the radio-only licence which costs 7.00 zł per month or 84.00 zł per year. The licence is collected and maintained by the Polish post office, Poczta Polska.

Around 60% of the fee goes to Telewizja Polska with the rest going to Polskie Radio. In return, public television is not permitted to interrupt its programmes with advertisements (advertisements are only allowed between programmes). The TV licence is waived for those over 75.[54] Only one licence is required for a single household irrespective of number of sets, but in case of commercial premises one licence for each set must be paid (this includes radios and TVs in company vehicles). However, public health institutions, all nurseries, educational institutions, hospices and retirement homes need to pay only single licence per building or building complex they occupy.

There is a major problem with licence evasion in Poland. There are two main reasons for the large amount. Firstly, licence collection based on the honesty-based opt-in system, rather than the systems of other countries of opt-out, i.e. a person liable to pay the licence has to register on their own so there is no effective means to compel people to register and to prosecute those that fail to do so. Also as the licensing inspectors, who are usually postmen, do not have the right of entry to inspect premises and must get the owner's or main occupier's permission to enter. Secondly, the public media are frequently accused of being pro-government propaganda mouthpieces, and not independent public broadcasters.[55] Due to this, it is estimated that back in 2012 around 65% of households evade the licence fee, compared to an average of 10% in the European Union.[56] In 2020, it was revealed that only 8% of Polish households paid the licence fee, and as a result the government gave a 2 billion złoty grant for public media.[57]

Portugal

RTP was financed through government grants and advertising. Since 1 September 2003, the public TV and radio has been also financed through a fee. The "Taxa de Contribuição Audiovisual" (Portuguese for Broadcasting Contribution Tax) is charged monthly through the electricity bills and its value is updated at the annual rate of inflation.[58]

Due to the economic crisis that the country has suffered, RTP's financing model has changed. In 2014, government grants ended, with RTP being financed only through the "Taxa de Contribuição Audiovisual" and advertising.[59] Since July 2016, the fee is €2.85 + VAT, with a final cost of €3.02 (€36.24 per year).[60]

RTP1 can only broadcast 6 minutes of commercial advertising per hour (while commercial televisions can broadcast 12 minutes per hour). RTP2 is a commercial advertising-free channel as well the radios stations. RTP3 and RTP Memória can only broadcast commercial advertising on cable, satellite and IPTV platforms. On DTT they are commercial advertising-free.

Serbia

Licence fees in Serbia are bundled together with electricity bills and collected monthly. There have been increasing indications that the Government of Serbia is considering the temporary cessation of the licence fee until a more effective financing solution is found.[61] However, as of 28 August 2013 this step has yet to be realized.

Slovakia

The licence fee in Slovakia is €4.64 per month (€55.68 per year).[62] In addition to the licence fee RTVS also receives state subsidies and money from advertising.

Slovenia

Since June 2013, the annual licence fee in Slovenia stands at €153.00 (€12.75 per month) for receiving both television and radio services, or €45.24 (€3.77 per month) for radio services only, paid by the month. This amount is payable once per household, regardless of the number of televisions or radios (or other devices capable of receiving TV or radio broadcasts). Businesses and the self-employed pay this amount for every set, and pay higher rates where they are intended for public viewing rather than the private use of its employees.[63]

The licence fee is used to fund national broadcaster RTV Slovenija. In calendar year 2007, the licence fee raised €78.1 million, or approximately 68% of total operating revenue. The broadcaster then supplements this income with advertising, which by comparison provided revenues of €21.6 million in 2007, or about 19% of operating revenue.[64]

South Africa

The licence fee in South Africa is R265 (about €23) per annum (R312 per year if paid on a monthly basis) for TV.[65] A concessionary rate of R70 is available for those over 70, and disabled persons or war veterans who are on social welfare. The licence fee partially funds the public broadcaster, the South African Broadcasting Corporation. The SABC, unlike some other public broadcasters, derives much of its income from advertising. Proposals to abolish licensing have been circulating since October 2009. The national carrier hopes to receive funding entirely via state subsidies and commercials. According to IOL.co.za: "Television licence collections for the 2008/09 financial year (April 1, 2008, to March 31, 2009) amounted to R972m." (almost €90m)

South Korea

In South Korea, the television licence fee (Korean: 수신료 징수제) is collected for the Korean Broadcasting System and Educational Broadcasting System and is ₩30,000 per year[66] (about €20.67). It has stood at this level since 1981, and now makes up less than 40% of KBS's income and less than 8% of EBS's income.[67] Its purpose is to maintain public broadcasting in South Korea, and to give public broadcasters the resources to do their best to produce and broadcast public interest programs. The fee is collected by the Korea Electric Power Corporation through electricity billing.

Switzerland

According to the Swiss law, any person who receives the reception of radio or television programs from the national public broadcaster SRG SSR must be registered and is subject to household licence fees. The licence fee is a flat rate CHF 365 per year for TV and radio for single households,[68] and CHF 730 for multiple households, e.g. old peoples homes.[69] Persons who receive federal old-age, survivors or disability support, diplomats, those who are deaf-blind and principal residence is not in Switzerland receives an exception to the fees. Households who can't receive broadcasting transmissions are exempt from the current fees up and until 2023, which afterwards will be required.[70] The collection of licence fees is managed by the company Serafe AG, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of the insurance collections agency Secon.[71] For businesses, the fee is based on the companies' annual turnover and an annual fee is on sliding-scale between nothing for businesses with an annual turnover of less than CHF 500,000, and CHF 35,590 per year for businesses with an annual turnover of over a billion francs. The fee is collected by the Swiss Federal Tax Administration.[72]

A large majority of the fees which totals CHF 1.2 billion goes to SRG SSR, while the rest of the money goes a collection of small regional radio and television broadcasters. Non-payment of licence fees means fines for up to CHF 100,000.

On 4 March 2018, there was an initiative on whether TV licensing should be scrapped under the slogan "No Billag", which was reference to the previous collector of the TV licence fees.[73][74][75] The parliament have advocated a no vote.[76] Voters had overwhelming rejected the proposal by 71.6% to 28.4% and in all cantons.[77]

Turkey

According to the law, a licence fee at the rate of 8% or 16%, depending on equipment type (2% from computer equipment, 10% from cellular phones, 0.4% from automotives) is paid to TRT (state broadcaster) by the producer/importer of the TV receiving equipment . Consumers indirectly pay this fee only for once, at initial purchase of the equipment. Also, 2% tax is cut from each household/commercial/industrial electricity bill monthly. Additionally, TRT is also receiving funding via advertisements.

No registration is required for purchasing TV receiver equipment, except for cellular phones, which is mandated by a separate law.

United Kingdom

A television licence is required for each household where television programmes are watched or recorded as they are broadcast, irrespective of the signal method (terrestrial, satellite, cable or the Internet). As of September 2016, users of BBC iPlayer must also have a television licence to watch on-demand television content from the service.[78] As of 1 April 2017, after the end of a freeze that began in 2010, the price of a licence may now increase to account for inflation. The licence fee in 2018 was £150.50 for a colour and £50.50 for a black and white TV Licence. As of April 2019, the licence fee is £154.50 for a colour and £52.00 for a black and white TV Licence.[79] As it is classified in law as a tax, evasion of licence fees is a criminal offence.[80] 204,018 people were prosecuted or fined in 2014 for TV licence offences: 173,044 in England, 12,536 in Wales, 4,905 people in Northern Ireland and 15 in the Isle of Man.[81][82]

The licence fee is used almost entirely to fund BBC domestic radio, television and internet services. The money received from the fee represents approximately 75% of the cost of these services, with most of the remainder coming from the profits of BBC Studios, a commercial arm of the corporation which markets and distributes its content outside of the United Kingdom, and operates or licences BBC-branded television services and brands.[83] The BBC also receives some funding from the Scottish Government via MG Alba to finance the BBC Alba Gaelic-language television service in Scotland. The BBC used to receive a direct government grant from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to fund television and radio services broadcast to other countries, such as the BBC World Service radio and BBC Arabic Television. These services run on a non-profit, non-commercial basis. The grant was abolished on 1 April 2014, leaving these services to be funded by the UK licence fee, a move which has caused some controversy.[84][85]

The BBC is not the only public service broadcaster. Channel 4 is also a public television service but is funded through advertising.[86] The Welsh language S4C in Wales is funded through a combination of a direct grant from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, advertising and receives some of its programming free of charge by the BBC (see above). These other broadcasters are all much smaller than the BBC. In addition to the public broadcasters, the UK has a wide range of commercial television funded by a mixture of advertising and subscription. A television licence is still required of viewers who solely watch such commercial channels, although 74.9% of the population watches BBC One in any given week, making it the most popular channel in the country.[87] A similar licence, mandated by the Wireless Telegraphy Act 1904, existed for radio, but was abolished in 1971.

Countries where the TV licence has been abolished

The following countries have had television licences, but subsequently abolished them:

Australia

Radio licence fees were introduced in Australia in the 1920s to fund the first privately owned broadcasters, which were not permitted to sell advertising. With the formation of the government-owned Australian Broadcasting Commission in 1932, the licence fees were used to fund ABC broadcasts while the privately owned stations were permitted to seek revenue from advertising and sponsorship. Television licence fees were also introduced in 1956 when the ABC began TV transmissions. In 1964 a television licence, issued on a punch card, cost £6 (A$12); the fine for not having a licence was £100 (A$200).

All licence fees were abolished in 1974 by the Australian Labor Party government led by Gough Whitlam on the basis that the near-universality of television and radio services meant that public funding was a fairer method of providing revenue for government-owned radio and television broadcasters.[88] The ABC has since then been funded by government grants, now totalling around A$1.13 billion a year, and its own commercial activities (merchandising, overseas sale of programmes, etc.).

Flemish region and Brussels

The Flemish region of Belgium and Brussels abolished its television licence in 2001. The Flemish broadcaster VRT is now funded from general taxation.

Walloon region

As of 1 January 2018, the licence fee in the Walloon region has been abolished. All licences still in effect at this point will remain in effect and payable until the period is up, but will not be renewed after that period (for example, a licence starting 1 April 2017 will still need to be paid until 31 May 2018. After this point, you will not need to pay for a licence).[5]

The licence fee in Belgium's Walloon region (encompassing the French and German speaking communities) was €100.00 for a TV and €0.00 for a radio in a vehicle (Government of Wallonia decree of 1 December 2008, article 1).[89] Only one licence was needed for each household with a functional TV receiver regardless of the number, but each car with a radio had to have a separate car radio licence. Household radios did not require a licence. The money raised by the fee was used to fund Belgium's French and German public broadcasters (RTBF and BRF respectively). The TV licence fee was paid by people with surnames beginning with a letter between A and J between 1 April and 31 May inclusive; those with surnames beginning with a letter between K to Z paid between 1 October and 30 November inclusive. People with certain disabilities were exempt from paying the television licence fee. Hotels and similar lodging establishments paid an additional fee of €50.00 for each additional functional TV receiver and paid between 1 January and 1 March inclusive.

Bulgaria

Currently, the public broadcasters Bulgarian National Television (BNT) and Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) are almost entirely financed by the national budget of Bulgaria. After the fall of Communism and the introduction of democracy in the 1990s, the topic of financing public television and radio broadcasting was widely discussed. One of the methods to raise funding was by collecting a user's fee from every citizen of Bulgaria. Parliament approved and included the fee in the Radio and Television Law; however, the president imposed a veto on the law and a public discussion on the fairness of the decision started. Critics said that this is unacceptable, as many people will be paying for a service they may not be using. The parliament decided to keep the resolution in the law but imposed a temporary regime of financing the broadcasters through the national budget. The law has not been changed to this day; however, the temporary regime is still in effect and has been constantly prolonged. As a result, there is no fee to pay and the funding comes from the national budget.

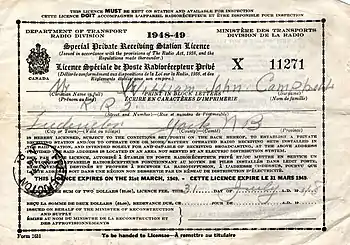

Canada

Canada eliminated its broadcasting receiver licence in 1953, replacing it with TV equipment excise taxes, shortly after the introduction of a television service.[90] The Radiotelegraph Act of 6 June 1913 established the initial Canadian policies for radio communication. Similar to the law in force in Britain, this act required that operation of "any radiotelegraph apparatus" required a licence, issued by the Minister of the Naval Service.[91] This included members of the general public who only possessed a radio receiver and were not making transmissions, who were required to hold an "Amateur Experimental Station" licence,[92] as well as pass the exam needed to receive an "Amateur Experimental Certificate of Proficiency", which required the ability to send and receive Morse code at five words a minute.[93] In January 1922 the government lowered the barrier for individuals merely interested in receiving broadcasts, by introducing a new licence category, Private Receiving Station, that removed the need to qualify for an amateur radio licence.[94][95] The receiving station licences initially cost $1 and had to be renewed yearly.

The licence fee eventually rose to $2.50 per year to provide revenue for both radio and television broadcasts by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, however, it was eliminated effective 1 April 1953.[90] This action exempted broadcast-only receivers from licensing, and the Department of Transport (DOT) was given authority to exempt other receiver types from licensing as it saw fit. DOT exempted all "home-type" receivers capable of receiving any radio communications other than "public correspondence" (defined as "radio transmissions not intended to be received by just anyone but rather by a member of the public who has paid for the message" – examples include ship-to-shore radiotelephone calls or car-phone transmissions). After 1952, licences were required in Canada only for general coverage shortwave receivers with single-sideband capability, and VHF/UHF scanners which could tune to the maritime or land mobile radiotelephone bands.

Beginning in 1982, in response to a Canadian court's finding that all unscrambled radio signals imply a forfeiture of the right to privacy, the DOC (Department of Communications) required receiver licensing only in cases where it was necessary to ensure technical compatibility with the transmitter.

Regulation SOR-89-253 (published in the 4 February 1989 issue of the Canada Gazette, pages 498–502) removed the licence requirement for all radio and TV receivers.

The responsibility for regulating radio spectrum affairs in Canada has devolved to a number of federal departments and agencies. It was under the oversight of the Department of Naval Service from 1913 until 1 July 1922, when it was transferred to civilian control under the Department of Marine and Fisheries,[96] followed by the Department of Transport (from 1935 to 1969), Department of Communications (1969 to 1996) and most recently to Industry Canada (since 1995).[97]

Cyprus

Cyprus used to have an indirect but obligatory tax for CyBC, its state-run public broadcasting service. The tax was added to electricity bills, and the amount paid depended on the size of the home. By the late 1990s, it was abolished due to pressure from private commercial radio and TV broadcasters. CyBC is currently funded by advertising and government grants.

Finland

On 1 January 2013, Finland replaced its television licence with a direct unconditional income public broadcasting tax (Finnish: yleisradiovero, Swedish: rundradioskatt) for individual taxpayers.[6][98][99] Unlike the previous fee, this tax is progressive, meaning that people will pay up to €163 depending on income. The lowest income recipients, persons under the age of eighteen years, and residents in the autonomous Åland Islands are exempt from the tax.[100]

Before the introduction of the Yle tax, the television fee in Finland used to be between €244.90 and €253.80 (depending on the interval of payments) per annum for a household with TV (as of 2011). It was the primary source of funding for Yleisradio (Yle), a role which has now been taken over by the Yle tax.

Gibraltar

It was announced in Gibraltar's budget speech of 23 June 2006 that Gibraltar would abolish its TV licence.[101] The 7,452[102] TV licence fees were previously used to part fund the Gibraltar Broadcasting Corporation (GBC). However, the majority of the GBC's funding came in the form of a grant from the government.

Hungary

In Hungary, the licence fees nominally exist, but since 2002 the government has decided to pay them out of the state budget.[103] Effectively, this means that funding for Magyar Televízió and Duna TV now comes from the government through taxation.

As of spring 2007, commercial units (hotels, bars etc.) have to pay television licence fees again, on a per-TV set basis.

Since the parliament decides on the amount of public broadcasters' income, during the 2009 financial crisis it was possible for it to decide to cut their funding by more than 30%. This move was publicly condemned by the EBU.[104]

The television licensing scheme has been a problem for Hungarian public broadcasters ever since the initial privatisation changes in 1995,[105][106] and the public broadcaster MTV has been stuck in a permanent financial crisis for years.[107]

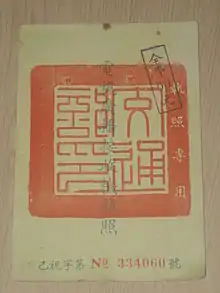

Hong Kong

Hong Kong had a radio and television licence fee imposed by Radio Hong Kong (RHK) and Rediffusion Television. The licence cost $36 Hong Kong dollars per year. Over-the-air radio and television terrestrial broadcasts were always free of charge since 1967, no matter whether they are analogue or digital.

There were public television programmes produced by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK). RTHK is funded by the Hong Kong Government, before having its TV channel, it used commercial television channels to broadcast its programmes, and each of the traditional four terrestrial commercial TV channels in Hong Kong (TVB Jade and ATV Home, which carried Cantonese-language broadcasts, and TVB Pearl and ATV World, which carried English-language broadcasts), were required to broadcast 2.5 hours of public television per week. However, there is no such requirement for newer digital channels.

As of 2017, RTHK has three digital television channels[108] RTHK 31, RTHK 32 and RTHK 33. RTHK's own programmes will return to RTHK's channels in the future.[109]

Iceland

The TV licence fee for Iceland's state broadcaster RÚV was abolished in 2007. Instead a poll tax of 17,200 kr. is collected from all people who pay income tax, regardless of whether they use television and radio.[110]

India

India introduced a radio receiver licence system in 1928, for All India Radio Aakaashavani. With the advent of television broadcasting in 1956–57, television was also licensed. With the spurt in television stations beginning 1971–72, a separate broadcasting company, Doordarshan, was formed. The radio and television licences in question needed to be renewed at the post offices yearly. The annual premium for radio was Rs 15 in the 1970s and 1980s. Radio licence stamps were issued for this purpose. License fees for TV were Rs 50. The wireless license inspector from the post office was authorized to check every house/shop for a WLB (Wireless License Book) and penalize and even seize the radio or TV. In 1984, the licensing system was withdrawn with both of the Indian national public broadcasters, AIR and Doordarshan, funded instead by the Government of India and by advertising.

Indonesia

The radio tax to supplement RRI funding was introduced in 1947,[111] about two years after its foundation and in height of the Indonesian National Revolution, initially set at Rp5 per month. The tax was abolished sometime in the 1980s.

Possibly shortly after TVRI begun broadcasting in 1962, the television fee later was also introduced. Originally the TVRI Foundation (Yayasan TVRI) was assigned to collect the fee, but in 1990 President Suharto enacted a presidential statement to give fee collecting authority to Mekatama Raya, a private company run by his son Sigit Harjojudanto and Suharto's cronies, in the name of the foundation starting in 1991. The problems surrounding the fee collection and the public protests making the company no longer collecting the fee a year later.[112] The television fee then slowly disappeared, though in some places such as Bandung the fee still exist as of 1998.[113]

According to Act No. 32 of 2002 on Broadcasting, the newly-transformed RRI and TVRI funding comes from several sources, one of them is the so-called "broadcasting fee" (Indonesian: iuran penyiaran). However, as of today the fee is yet to be implemented. Currently the funding of the two comes primarily from the annual state budget and "non-tax state revenue", either by advertising or other sources regulated in government regulations.

Israel

Israel's television tax was abolished in September 2015, retroactively to January 2015.[114] The television licence for 2014 in Israel for every household was ₪ 345 (€73) and the radio licence (for car owners only) was ₪ 136 (€29). The licence fee was the primary source of revenue for the Israel Broadcasting Authority, the state broadcaster, which was closed down and replaced by the Israeli Broadcasting Corporation in May 2017; however, its radio stations carry full advertising and some TV programmes are sponsored by commercial entities and the radio licence (for car owners only) for 2020 is ₪ 164 (€41).[115]

Liechtenstein

To help fund a national cable broadcasting network between 1978 and 1998 under the Law on Radio and television, Liechtenstein demanded an annual household broadcasting licence for households that had broadcasting receiving equipment. The annual fee which was last requested in 1998, came to CHF 180.[116] In total, this provided an income of 2.7 million francs of which 1.1 million went the PTT and CHF 250,000 to the Swiss national broadcaster SRG. Since then, the government replaced this with an annual government grant for public media of CHF 1.5 million which is administrated under the supervision of the Mediakommision.

The sole radio station of the principality Radio Liechtenstein, was founded as a private commercial music station in 1995. In 2004, it was nationalised by the government under the ownership of Liechtensteinischer Rundfunk, to create a domestic public broadcasting station broadcasting news and music. The station is funded by commercials and the public broadcasting grant. A commercial television station, 1FLTV, was launched in August 2008.

There have been suggestions of reintroducing a public broadcasting fee in Liechtenstein, and in the 2014–2017 government, budget outlined such as a proposal. However, this was rejected in 2015. One possible reason is that two-thirds of the listenership of Radio Liechtenstein is Swiss and they wouldn't pay such a fee.

Malaysia

Until it was discontinued in April 2000,[117] television licence in Malaysia was paid on an annual basis of MYR 24 (MYR 2 per month), one of the lowest fees for television service in the world. Now, RTM is funded by government tax and advertising, whilst Media Prima owned another four more private broadcasting channels of TV3, NTV7, 8TV and TV9. The other two, TV Alhijrah and WBC are smaller broadcasters. Astro is a paid television service, so they operate by the monthly fees given to them by customers, and it is the same thing for HyppTV and ABNXcess.

Malta

The licence fee in Malta was €34.90.[118] It was used to fund the television (TVM) and radio channels (Radio Malta and Radju Parliament) run by Public Broadcasting Services. Approximately two-thirds of TVM's funding came from the licence fee, with much of the remainder coming from commercials.[119] Malta's television licence was abolished in 2011 when the free-to-air system was discontinued.

Netherlands

Since 1967, advertising has been introduced on public television and radio, but this was only allowed as a small segment before and after news broadcasts. It wasn't until the late 1980s so-called "floating commercial breaks" were introduced, these breaks are usually segments of multiple commercials with a total duration of 1 to 3 minutes and are placed in-between programmes, to allow programmes themselves to run uninterrupted. At the time, advertising on Sundays still wasn't yet allowed, mainly in part due to the heavy influence of the churches. In 1991 advertising on Sundays slowly began to take place.

With the plan to abolish the licence fee in 2000 due to the excessive collection costs[118] and to pay for public television from government funds, income tax was increased[118] in the late 1990s and maximum run time of commercial breaks was extended to 5 and 7 minutes. The Netherlands Public Broadcasting is now funded by government subsidy and advertising. The amount of time used by commercial breaks may not exceed 15% of the daily available broadcasting time and 10% of the total yearly available time.

New Zealand

Licence fees were first used in New Zealand to fund the radio services of what was to become the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation. Television was introduced in 1960 and with it the television licence fee, later known as the public broadcasting fee. This was capped at NZ$100 a year in the 1970s, and the country's two television channels, while still publicly owned, became increasingly reliant on advertising. From 1989, it was collected and disbursed by the Broadcasting Commission (NZ On Air) on a contestable basis to support local content production. The public broadcasting fee was abolished in July 1999.[120] NZ On Air was then funded by a direct appropriation from the Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

North Macedonia

As of 19 January 2017, the licence fee was abolished.

The licence fee in the Republic of North Macedonia was around €26 per year.[121] Until 2005 it was collected monthly as part of the electricity bill. The Law on Broadcasting Activity, which was adopted in November 2005, reads that the Public Broadcasting Service – Macedonian Radio and Television (MRT) shall collect the broadcast fee. The funds collected from the broadcasting fee are allocated in the following manner:

- 72% for MRT for covering costs for creating and broadcasting programmes;

- 4.5% for MRT for technical and technological development;

- 16% for MRD (Makedonska Radiodifuzija – Public operator of the transmission networks of the Public Broadcasting Service) for maintenance and use of the public broadcasting network;

- 3.5% for MRD for public broadcasting network development and

- 4% for the Broadcasting Council for regulating and development of the broadcasting activity in the Republic of North Macedonia.

The MRT shall keep 0.5% of the collected funds from the broadcasting fee as a commission fee.

However, MRT still has not found an effective mechanism for collection of the broadcast tax, so it has suffered a severe underfunding in recent years.

The Macedonian Government decided to update the Law on Broadcasting authorizing the Public Revenue Office to be in charge of the collection of the broadcast fee.

In addition to broadcast fee funding, Macedonian Radio-Television (MRT) also takes advertising and sponsorship.

The broadcasting fee is paid by hotels and motels are charged one broadcasting fee for every five rooms, legal persons and office space owners are obliged to pay one broadcasting fee to every 20 employees or other persons that use the office space, owners of catering and other public facilities possessing a radio receiver or TV set must pay one broadcasting fee for each receiver/set.

The Government of the Republic of North Macedonia, upon a proposal of the Broadcasting Council, shall determine which broadcasting fee payers in populated areas that are not covered by the broadcasting signal shall be exempt from payment of the broadcasting fee. The households with a blind person whose vision is impaired over 90% or families with a person whose hearing is impaired with an intensity of over 60 decibels, as determined in compliance with the regulations on disability insurance, where exempt from the duty to pay the broadcasting fee for the household where the family of the person lives.

As of 19 January 2017, the licence fee was abolished, citizens are exempt from paying this fee. Macedonian Radio and television, Macedonian Broadcasting and the Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services will be financed directly from the Budget of the Republic of North Macedonia.[122]

Norway

The licence fee in Norway was abolished in January 2020. Before that there was a mandatory fee for every household with a TV. The fee was c. 3000 kr (c. €305) per annum in 2019. The fee was mandatory for any owner of a TV set, and was the primary source of income for Norsk Rikskringkasting (NRK).[123] The licence fee was charged on a per household basis; therefore, addresses with more than one television receiver generally only required a single licence. An exception was made if the household includes persons living at home who no longer was provided for by the parents, e.g. students living at home. If people not in parental care own a separate television they had to pay the normal fee.[124]

Romania

The license fee in Romania was abolished in 2017.[125]

In the past, the licence fee in Romania for a household was 48 RON (€10.857) per year.[126] Small businesses paid about €45 and large businesses about €150. The licence fee was collected as part of the electricity bill. The licence fee makes up part of Televiziunea Română's funding, with the rest coming from advertising and government grants. However, some people allege that it is paid twice (both to the electricity bill and the cable or satellite operator indirectly, although cable and satellite providers are claiming they are not). In Romania, people must prove that they don't own a TV receiver in order not to pay the licence fee, but if they own a computer, they will have to pay, as they can watch TVR content online. Some people have criticized this, because, in the last years, TVR lost a lot of their supervisors, and also because with the analogue switch-off on 17 June 2015, it is still not widely available on digital terrestrial, and it is encrypted on satellite TV (a decryption card and a satellite receiver with card reader must be bought). Also, TVR will shift to DVB-T2, and with many sets only being sold with DVB-T, TVR will become unavailable to some users without a digital terrestrial receiver. The fee couldn't be avoided, however, as it was to be part of the electricity bill.

In 2016 the Parliament of Romania decided to abolish the fee on 1 January 2017.[125]

Singapore

Residents of Singapore with TVs in their households or TVs and radios in their vehicles were required to acquire the appropriate licences from 1963 to 2010. The cost of the TV licence for a household in Singapore was S$110.[127] Additional licences were required for radios and TVs in vehicles (S$27 and S$110 respectively).

The licence fee for television and radio was removed with immediate effect from 1 January 2011. This was announced during Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam's budget statement on 18 February 2011. Mr Shanmugaratnam chose to abolish the fees as they were "losing their relevance".[128]

Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, until 1961, all radio and TV receivers were required to be registered in local telecommunication offices and subscription fee were to be paid monthly. Compulsory registration and subscription fees were abolished on 18 August 1961, and prices on radio and TV receivers were raised to compensate the lost fees.[129] The fee was not re-introduced in the Russian Federation when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Sweden

On 1 January 2019, the television licence (Swedish: TV-avgift, literally TV fee) in Sweden was scrapped and replaced by a "general public service fee" (Swedish: allmän public service-avgift), which is a flat income-based public broadcasting tax of 1% per person, capped at 1,300 Swedish kronor (approximately US$145 or €126) per year.[130] The administration of the fee is done by the Swedish Tax Agency (Swedish: Skatteverket),[131] on behalf of the country's three public broadcasters Sveriges Television, Sveriges Radio and Sveriges Utbildningsradio. The fee pays for 5 TV channels, 45 radio channels, and TV and radio on the internet.

Previously the television licence was a household-based flat fee; it was last charged in 2018 at kr 2,400 per annum.[132] It was payable in monthly, bimonthly, quarterly or annual instalments,[133] to the agency Radiotjänst i Kiruna, which is jointly owned by SVT, SR and UR. The fee was collected by every household or company containing a TV set, and possession of such a device had to be reported to Radiotjänst as required by law. One fee was collected per household regardless of the number of TV sets either in the home or at alternate locations owned by the household, such as summer houses. Although the fee also paid for radio broadcasting, there is no specific fee for radios, the individual radio licence having been scrapped in 1978.[134] Television licence evasion suspected to be around 11 to 15%.[135] Originally it was referred as the "television licence" (Swedish: TV-licens), however it was replaced in the 2000s by term "television fee".

Republic of China (Taiwan)

Between 1959 and the 1970s, all radio and TV receivers in Taiwan were required to have a licence with an annual fee of NT$60. The practice was to prevent influence from mainland China (the People's Republic of China) by tuning in to its channels.[136]

Countries that have never had a television or broadcasting licence

Andorra

Ràdio i Televisió d'Andorra, the public broadcaster, is funded by both advertising and government grants, there is no fee.

Brazil

In Brazil, there is no fee or TV license. The Padre Anchieta Foundation, which manages TV Cultura and the Cultura FM and Cultura Brasil radio stations, is financed through lendings from the State Government of São Paulo and advertisements and cultural fundraising from the private sector. Empresa Brasil de Comunicação, which manages TV Brasil and public radio stations (Rádio MEC and Rádio Nacional), is financed from the Federal Budget, besides profit from licensing and production of programs, institutional advertisement, and service rendering to public and private institutions.[137] The public resources dedicated to TV Cultura (that is, the gross budget of the Foundation) was R$74.7 million in 2006, but of those R$36.2 million were donated from private industry partners and sponsors.[138]

China

China has never had a television licence fee to pay for the state broadcaster. The current state broadcaster, China Central Television (CCTV), established in 1958, is funded almost entirely through the sale of commercial advertising time, although this is supplemented by government funding and a tax of ¥2 per-month from all cable television subscribers in the country.

Estonia

In Estonia there are three public TV channels: Eesti Televisioon ETV, ETV2, and ETV+ (ETV+ was launched on 27 September 2015 and mostly targets people who speak Russian). The funding comes from government grant-in-aid. Around 15% of which was until 2008 funded by the fees paid by Estonian commercial broadcasters in return for their exclusive right to screen television advertising. Showing commercials in public broadcasting television was stopped in 2002 (after a previous unsuccessful attempt in 1998–1999). One argument was that its low-cost advertising rates were damaging the ability of commercial broadcasters to operate. The introduction of a licence fee system was considered but ultimately rejected in the face of public opposition.[139]

ETV is currently one of only a few public television broadcasters in the European Union which has neither advertising nor a licence fee and is solely funded by national governments grants. At the moment, only RTVE of Spain has a similar model, and from 2013 and onwards, the Finnish Yle broadcaster will follow suit.[140]

Iran

Iran has never levied television licence fees. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, National Iranian Radio and Television was renamed Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, and it became the state broadcaster. In Iran, private broadcasting is illegal.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg has never had a television licence requirement; this is because until 1993, the country has never had its own national public broadcaster. The country's first and main broadcaster, RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg, is a commercial network financed by advertising, and the only other national broadcaster is the public radio station Radio 100,7, a small radio station funded by the country's Ministry of Culture and sponsorship . The majority of television channels based in Luxembourg are owned by the RTL Group and include both channels serving Luxembourg itself, as well as channels serving nearby countries such as Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, but nominally operating out of and available in Luxembourg.

Monaco

Monaco has never had any kind of listener or viewer broadcasting licence fee. Since the establishment of both Radio Monte-Carlo in 1943 and Télévision Monte-Carlo in 1954, there has never been a charge to pay for receiving the stations as both were entirely funded on a commercial basis.

Nigeria

Television licences are not used in Nigeria, except in the sense of broadcasting licences granted to private networks. The federal government's television station, NTA (Nigerian Television Authority), has two broadcast networks – NTA 1 and NTA 2. NTA 1 is partly funded by the central government and partly by advertising revenue, while NTA 2 is wholly funded by advertisements. Almost all of the thirty-six states have their own television stations funded wholly or substantially by their respective governments.

Spain

RTVE, the public broadcaster, had been funded by government grants and advertising incomes since it was launched in 1937 (radio) and 1956 (television). Although the state-owner national radio stations removed all its advertising in 1986, its public nationwide TV channels continued broadcasting commercial breaks until 2009. Since 2010, the public broadcaster is funded by government grants and taxes paid by private nationwide TV broadcasters and telecommunications companies.[141]

United States

In the United States, historically, privately owned commercial radio stations selling advertising quickly proved to be commercially viable enterprises during the first half of the 20th century; though a few governments owned non-commercial radio stations (such as WNYC, owned by New York City from 1922 to 1997), most were owned by charitable organizations and supported by donations. The pattern repeated itself with television in the second half of that century, except that some governments, mostly states, also established educational television stations alongside the privately owned stations.

The United States created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) in 1967, which eventually led to the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR); however, those are loose networks of non-commercial educational (NCE) stations owned by state and local governments, educational institutions, or non-profit organizations, more like U.S. commercial networks (though there are some differences) than European public broadcasters. The CPB and virtually all government-owned stations are funded through general taxes, and donations from individual persons (usually in the form of "memberships") and charitable organizations. Individual programs on public broadcasters may also be supported by underwriting spots paid for by sponsors; typically, these spots are presented at the beginning and conclusion of the program. Because between 53 and 60 percent of public television's revenues come from private membership donations and grants,[142] most stations solicit individual donations by methods including fundraising, pledge drives or telethons which can disrupt regularly scheduled programming. Normal programming can be replaced with specials aimed at a wider audience to solicit new members and donations.[143]

The annual funding for public television in the United States was US$445.5 million in 2014 (including interest revenue).[144]

In some rural portions of the United States, broadcast translator districts exist, which are funded by an ad valorem property tax on all property within the district,[145] or a parcel tax on each dwelling unit within the district. Failure to pay the TV translator tax has the same repercussions as failing to pay any other property tax, including a lien placed on the property and eventual seizure.[146] In addition, fines can be levied on viewers who watch TV from the signals from the translator without paying the fee. As the Federal Communications Commission has exclusive jurisdiction over broadcast stations, whether a local authority can legally impose a fee merely to watch an over-the-air broadcast station is questionable. Depending on the jurisdiction, the tax may be charged regardless of whether the resident watches TV from the translator or instead watches it via cable TV or satellite, or the property owner may certify that they do not use the translator district's services and get a waiver.

Another substitute for TV licences comes through cable television franchise fee agreements. The itemized fee on customers' bills is included or added to the cable TV operator's gross income to fund public, educational, and government access (PEG) television for the municipality that granted the franchise agreement. State governments also may add their own taxes. These taxes generate controversy since these taxes sometimes go into the general fund of governmental entities or there is double taxation (e.g., a tax funds public-access television, but the cable TV operator must pay for the equipment or facilities out of its own pocket anyway, or the cable TV operator must pay for earmark projects of the local municipality that are not related to television).

Vietnam

Today, almost all television channels in Vietnam carry advertisements, although these networks are state-owned and the media is heavily censored. Now-defunct television and radio stations that operated in the former North and South had almost no commercials, and were also government-funded and run.

Detection of evasion of television licences

In many jurisdictions, television licences are enforced. Besides claims of sophisticated technological methods for the detection of operating televisions, detection of illegal television sets can be as simple as the observation of the lights and sounds of an illegally used television in a user's home at night.

United Kingdom

Detection is a fairly simple matter because nearly all homes are licensed, so only those homes that do not have a licence need to be checked.

The BBC claims that "television detector vans" are employed by TV Licensing in the UK, although these claims are unverified by any independent source.

An effort to compel the BBC to release key information about the television detection vans (and possible handheld equivalents) based on the Freedom of Information Act was rejected.[147] The BBC has stated on record "... detection equipment is complex to deploy as its use is strictly governed by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) and the Regulation of Investigatory Powers (British Broadcasting Corporation) Order 2001. RIPA and the Order outline how the relevant investigatory powers are to be used by the BBC and ensure compliance with human rights.[148]

Opinions of television licensing systems

Advocates argue that one of the main advantages of television fully funded by a licence fee is that programming can be enjoyed without interruptions for advertisements. Television funded by advertising is not truly free of cost to the viewer, since the advertising is used mostly to sell mass-market items, and the cost of mass-market goods includes the cost of TV advertising, such that viewers effectively pay for TV when they purchase those products. Viewers also pay in time lost watching advertising.

Europeans tend to watch one hour less TV per day than do North Americans,[149] but in practice may be enjoying the same amount of television but gaining extra leisure time by not watching advertisements. Even the channels in Europe that do carry advertising carry about 25% less advertising per hour than their North American counterparts.[150]

Critics of receiver licensing point out that a licence is a regressive form of taxation, because poor people pay more for the service in relation to income.[151] In contrast, the advertisement model implies that costs are covered in proportion to consumption of mass-market goods, particularly luxury goods, so the poorer the viewer, the greater the subsidy. The experience with broadcast deregulation in Europe suggests that demand for commercial-free content is not as high as once thought.

The third option, voluntary funding of public television via subscriptions, requires a subscription level higher than the licence fee (because not all people that currently pay the licence would voluntarily pay a subscription) if quality and/or output volume are not to decline. These higher fees would deter even more people from subscribing, leading to further hikes in subscription levels. In time, if public subscription television were subject to encryption to deny access to non-subscribers, the poorest in society would be denied access to the well-funded programmes that public broadcasters produce today in exchange for the relatively lower cost of the licence.

In 2004, the UK government's Department for Culture, Media and Sport, as part of its BBC Charter review, asked the public what it thought of various funding alternatives. Fifty-nine per cent of respondents agreed with the statement "Advertising would interfere with my enjoyment of programmes", while 31 per cent disagreed; 71 per cent agreed with the statement "subscription funding would be unfair to those that could not pay", while 16 per cent disagreed. An independent study showed that more than two-thirds of people polled thought that, due to TV subscriptions such as satellite television, the licence fee should be dropped. Regardless of this however the Department concluded that the licence fee was "the least worse [sic] option".[152]

Another problem, governments use tax money pay for content and content should become public domain but governments give public companies like the British Broadcasting Corporation content monopoly against the public (companies copyright content, people can't resale, remix, or reuse content from their tax money).[153]

In 2005, the British government described the licence fee system as "the best (and most widely supported) funding model, even though it is not perfect".[154][155] That is, they believe that the disadvantages of having a licence fee are less than the disadvantages of all other methods. In fact, the disadvantages of other methods have led to some countries, especially those in the former Eastern Bloc, to consider the introduction of a TV licence.

Both Bulgaria[156] and Serbia[157] have attempted to legislate to introduce a television licence. In Bulgaria, a fee is specified in the broadcasting law, but it has never been implemented in practice. Lithuania[158] and Latvia have also long debated the introduction of a licence fee but so far made little progress on legislating for one. In the case of Latvia, some analysts believe this is partly because the government is unwilling to relinquish the control of Latvijas Televīzija that funding from general taxation gives it.[159]

The Czech Republic[160] has increased the proportion of funding that the public broadcaster gets from licence fees, justifying the move with the argument that the existing public service broadcasters cannot compete with commercial broadcasters for advertising revenues.

Internet-based broadcast access

The development of the global Internet has created the ability for television and radio programming to be easily accessed outside of its country of origin, with little technological investment needed to implement the capability. Before the development of the Internet, this would have required specially-acquired satellite relaying and/or local terrestrial rebroadcasting of the international content, at considerable cost to the international viewer. This access can now instead be readily facilitated using off-the-shelf video encoding and streaming equipment, using broadband services within the country of origin.

In some cases, no additional technology is needed for international program access via the Internet, if the national broadcaster already has a broadband streaming service established for citizens of their own country. However, countries with TV licensing systems often do not have a way to accommodate international access via the Internet, and instead work to actively block and prevent access because their national licensing rules have not evolved fast enough to adapt to the ever-expanding potential global audience for their material.

For example, it is not possible for a resident of the United States to pay for a British TV Licence to watch all of the BBC's programming, streamed live over the Internet in its original format.

References

- "SATKurier.pl / TVP / Koszty i zyski TVP jako telewizji publicznej". Satkurier.pl. Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "European Convention on Transfrontier Television – CETS No.: 132". Council of Europe. 5 May 1989. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- "License Fee". Encyclopedia of Television (1st Edition). Chicago: Museum of Broadcast Communications. 1997. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- (total of TV and radio licences)

- "Redevance TV : questions suite à sa suppression en 2018". Portail de la Wallonie (in French). Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "End of the road for TV license fees". Yle Uutiset. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "Újra eltörlik az üzembentartási díjat". NÉPSZAVA online. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "About licensing fees in Iceland in icelandic". Ruv.is. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "The radio and TV fee is being replaced". Radiotjänst. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- €179.90 colour / €59.20 monochrome

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Übersicht". GIS (in German). Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Open Society Institute, EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program; Network Media Program. (2005). Television across Europe: regulation, policy and independence: Bosnia and Herzegovina (PDF). EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program (EUMAP)/ Open Society Institute (OSI). pp. 253–338. ISBN 978-1-891385-35-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Croatian Parliament (19 February 2003). "Zakon o Hrvatskoj radioteleviziji (The Croatian Radio-Television Act)" (in Croatian). Narodne novine NN 2003/25. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- Open Society Institute, EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program; Network Media Program. (2005). Television across Europe: regulation, policy and independence: Croatia (PDF). EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program (EUMAP)/ Open Society Institute (OSI). pp. 425–481. ISBN 978-1-891385-35-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Statut Hrvatske Radiotelevizije" (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 26 June 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Czech Television in 2009, Czech Television.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/545850/annual-tv-and-radio-licence-fees-in-denmark/

- "Bekendtgørelse om licens". Retsinformation.dk. 29 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Forside – dr.dk/OmDR". Dr.dk. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "Så meget af din licens får staten – Medier & reklamer". Business.dk. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "Denmark scraps public TV licence fee". Broadband TV News. 18 March 2018.

- https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F88