Tlatilco culture

Tlatilco culture is a culture that flourished in the Valley of Mexico between the years 1250 BCE and 800 BCE,[1] during the Mesoamerican Early Formative period. Tlatilco, Tlapacoya, and Coapexco are the major Tlatilco culture sites.

Tlatilco culture shows a marked increase in specialization over earlier cultures, including more complex settlement patterns, specialized occupations, and stratified social structures. In particular, the development of the chiefdom centers at Tlatilco and Tlapacoya is a defining characteristic of Tlatilco culture.

This period also saw a significant increase in long distance trade, particularly in iron ore, obsidian, and greenstone, trade which likely facilitated the Olmec influence seen within the culture, and may explain the discovery of Tlatilco-style pottery near Cuautla, Morelos, 90 miles (140 km) to the south.[2]

Defining the Tlatilco culture

Archaeologically, the advent of the Tlatilco culture is denoted by a widespread dissemination of artistic conventions, pottery, and ceramics known as the Early Horizon (also known as the Olmec or San Lorenzo Horizon), Mesoamerica's earliest archaeological horizon.[3]

Specifically, the Tlatilco culture is defined by the presence of:[4]

- Both ritual and utilitarian ceramics.

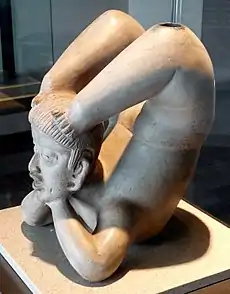

- Both animal and human figurines rendered in a somewhat stylized manner.

- Clay masks and other exotic ritual objects.

- Elaborate burials with grave offerings.

- Olmec-style decorations, motifs, designs, and figurines such as the hollow "baby-face" figurines or the pilli-style costumed males.

The Olmec influence is unmistakable. One survey of Tlatilco graves found that Olmec-style objects were "ubiquitous" in the earliest upper-middle status burials but were unrelated to wealth. That is, no correlation was found between the markers of high status and Olmec-style objects, and although larger numbers of Olmec-style objects were found in rich graves, they constituted a smaller percentage of the grave goods there.[5]

Phases

Christine Niederberger Betton, in her landmark 1987 archaeological study of the Valley of Mexico, identified two phases of the Tlatilco culture:

- Ayotla (Coapexco) phase, 1250 - 1000 BCE

- Manantial phase, 1000 - 800 BCE.[6]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

The Olmec-style artifacts appear suddenly, abundantly, and pervasively in the archaeological record at the outset of the Ayotla (Coapexco) phase.[7]

At the end of the Ayotla, however, around 1000 BCE, there is another abrupt change in ceramics: figurines of costumed males give way to those of nude females, and Olmec-derived iconography evolves into a more native appearance, changes likely reflective of a change in religious ideas and practices.[8]

By 800 BCE, the hallmarks of the Tlatilco culture fade from the archaeological record. By 700 BCE, Cuicuilco had become the largest and most dynamic city in the Valley of Mexico, eclipsing Tlatilco and Tlapacoya.

See also

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the Tlatilco culture. |

- These dates, from Diehl and from Bradley and Joralemon, are radiocarbon dates, which are earlier in Mesoamerica than the corresponding chronological dates -- chronologically, the Tlatilco culture lasts from 1450 BCE until 900 BCE (Pool, p. 7). Tolstoy, however, gives slightly different dates.

- Grove discusses ceramics "identical with certain vessels found in association with Preclassic burials at Tlatilco" (p. 62).

- Pool, p. 181.

- Diehl, p. 153-160.

- Tolstoy, p. 119.

- Dates from Bradley & Joralemon, p. 13. Tolstoy defines separate Coapexco and Ayotla phases (p. 283).

- Tolstoy, who says that the Olmec-style artifacts pervade "general refuse, all households and many sectors of activity", p. 98.

- Bradley and Joralemon, p. 28, who wonder whether the transition between the Ayotla and Manantial phases was not caused by the decline of the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan ceremonial center. Also echoed by Pool, p. 206, who states that "Early Horizon motifs underwent substantial development".

References

- Bradley, Douglas E., and Peter David Joralemon (1993) The Lords of Life: The Iconography of Power and Fertility in Preclassic Mesoamerica, Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London.

- Grove, David C. (1970) "The San Pablo Pantheon Mound: a Middle Preclassic Site Found in Morelos, Mexico", in American Antiquity, v35 n1, January 1970, pp. 62–73.

- Niederberger Betton, Christine (1987) Paléo-paysages et archéologie pré-urbaine du Bassin de Mexico, Centre d’études mexicaines et centraméricaines (CEMCA), coll. Études Mésoaméricaines, 2 vols, México.

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3.

- Tolstoy, Paul (1989) "Coapexco and Tlatilco: sites with Olmec materials in the Basin of Mexico", Regional Perspectives on the Olmec, Robert Sharer, ed., Cambridge University Press, pp. 85–121, ISBN 978-0-521-36332-7.