Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory

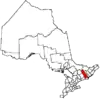

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory is the main First Nation reserve of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation. The territory is located on the Bay of Quinte in Ontario, east of Belleville, Ontario. Tyendinaga is located near the site of the former village of Ganneious.[3]:10

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory

Kenhtè:ke | |

|---|---|

| Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory Indian Reserve | |

Novelty statue at the Mohawk Plaza on Highway 49 | |

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory | |

| Coordinates: 44°11.5′N 77°08′W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Hastings |

| First Nation | Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte |

| Settled | 1784 |

| Formed | 1793 (official deed) |

| Government | |

| • Chief | Donald Maracle |

| • Federal riding | Hastings-Lennox and Addington |

| • Prov. riding | Hastings—Lennox and Addington |

| Area | |

| • Land | 71.06 km2 (27.44 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 2,525 |

| • Density | 29.9/km2 (77/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal Code | K0K |

| Area code(s) | 613 |

| Website | www.mbq-tmt.org |

History

Prior to founding

According to the official history of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, Tyendinaga was the birthplace of The Great Peacemaker, who was instrumental in the founding of the Haudenosaunee in the 12th century.[4] Various non-Indigenous scholars have disputed the dating of this event, suggesting that it may have taken place in the 15th century, but there is no consensus.[5][6]

18th century

During much of the eighteenth century, the land that would later become the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory was populated by Mississaugas.[7] Beginning in 1784, the territory was settled by Mohawks, who had been displaced from their home in Fort Hunter, New York by the victory of the United States in the American Revolutionary War. The chief of the Fort Hunter Mohawks was John Deserontyon, a Loyalist Captain who had fought alongside the British Empire during the war.[3]:11 At first, Deserontyon faced criticism for his chosen site of relocation from fellow chief Joseph Brant (who preferred to settle in the valley of the Grand River), as well as British colonial officials Frederick Haldimand and Sir John Johnson, who had been placed in charge of managing the resettlement.[8] Nonetheless, the Mohawks were granted land on the Bay of Quinte, part of the land reserved for resettlement of Loyalists by the Crawford Purchase of 1783. On May 22, 1784, about 20 Mohawk families, comprising a total of 100-125 individuals, arrived in the area after canoeing from Lachine, Quebec. This landing of the first families is commemorated annually with a re-enactment and a thanksgiving for the safe arrival.[4]

Throughout the 1780s, the settlement grew and developed, including the appointment of an Indian Department-paid teacher named Vincent to the settlement, and the construction of a schoolhouse and a church, completed in 1791.[8] In 1788, when the settlement had a population of about one hundred, Fort Hunter Mohawk captains Kanonraron (Aaron Hill) and Anoghsoktea (Isaac Hill) came to the territory after leaving the Grand River settlement under Joseph Brant, whom they resented for his growing political influence and policy of encouraging white settlers among the Mohawks.[8][9] After repeated requests, including a petition to King George III by Sir John Johnson in 1785,[10] the Mohawks that had settled at the Bay of Quinte were granted a 12 by 13 mile tract of land on the bay by Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada John Graves Simcoe on 1 April 1793, in what is known as the Simcoe Deed, the Crown Grant to the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, and Treaty 3 1/2.[8][11][12]

Near the very end of the century, factionalism broke out on the Territory, with Isaac Hill challenging Deserontyon's leadership and ultimately killing two of Deserontyon's relatives. The issue was settled in a council that took place from the 2nd to the 10th of September, 1800, called by Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs William Claus, when Hill agreed to exclude himself from the affairs of the Territory.[8][13]

19th century

Throughout the first few decades of the 19th century, Mohawks on the Territory raised objections to the government leasing land to white settlers that had been guaranteed to them in the Simcoe Deed, largely for the removal of timber.[8][14] After the death of John Deserontyon in January 1811, and the end of the War of 1812, a further wave of non-Indigenous settlement arrived in the area. A letter dated 5 March 1819 records that in the area were settled "descendants of Germans; there is also a family of immediate descendants of Africans... [t]here are also some descendants of Americans."[15] From 1820 to 1843, the government of Canada allowed United Empire Loyalists to settle on the Territory, despite repeated appeals by the Mohawks for the government to remove the interlopers.[4][16] By the end of that period, two-thirds of the land base was under private ownership,[4] including an 800-acre tract of land sold circa 1836 to John Deserontyon's grandson, John Culbertson, which eventually became the townsite of Deseronto, Ontario (named after John Deserontyon). Since the 1830s, there have been allegations that the sale was illegal, and that dispute forms the basis of The Culbertson Tract Land Claim by the First Nation.[17]

In 1843, the Mohawks constructed the Gothic chapel Christ Church on the Territory. It was later designated Her Majesty's Chapel Royal of the Mohawk by Elizabeth II in 2004, making it one of only six Royal Chapels outside of Great Britain.[4]

In 1860, Oronhyatekha came to teach at Tyendinaga after studying briefly at Kenyon College. In the subsequent years, he left the Territory to spend time at Six Nations, and then studied for a few months at the University of Oxford at the recommendation of the Prince of Wales' personal physician, Henry Acland, finally returning to Tyendinaga in 1863, whereupon he married Deyoronseh (Ellen Hill). His home in Tyendinaga was known as "The Pines", a palatial Victorian estate where he only allowed the Mohawk language to be spoken. In April 1871,[18] Oronhyatekha was appointed the physician for Tyendinaga while he was practising medicine in Napanee. Deyoronseh's family owned Captain John's Island in the Bay of Quinte, which Oronhyatekha renamed Forester's Island (after the Independent Order of Foresters, the expansion of which he had been instrumental in) in the 1890s. On the island, Oronhyatekha built two homes, several cottages, a hotel, a dining hall, a bandstand, and a wharf. He began the construction of an orphanage on the island in 1903, which was opened in 1906 before being sold in 1908. Oronhyatekha had died in Savannah, Georgia in March 1907, a few months before his son Dr. Acland Oronhyatekha (also known as William Acland Heywood), Chief of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte also died.[19][20][21]

The first council election for the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte band government, as established under the Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869, took place in October 1870. The first meeting of the first elected council took place December 10, 1870, and the men listed as "chiefs" of that council were Chief Sampson Green (Annosothkah, an alternate spelling of Isaac Hill's Mohawk name-- Green was Hill's great-grandson), Chief Archibald Culbertson, Chief William J. W. Hill (a descendant of John Desorontyon and Joseph Brant Thayendanegea), Chief John Loft (another descendant of Isaac Hill), Chief Seth W. Hill (also a descendant of Isaac Hill), Chief Cornelius Maricle, and Chief John Claus.[18]

20th century

By 1971, negotiations were complete to construct a centralized elementary school building on York Road, to replace the overcrowded Quinte Mohawk Indian Day School, which had been built around 1955 and served students up to Grade 8, and three poorly-insulated single-room schoolhouses constructed before the 1920s.[22] Construction of Quinte Mohawk School began on August 28, 1973, and the school opened in September 1974 with around 230 students.[22]

First Nations Technical Institute (today known as FNTI) was created in 1985, as an Indigenous-owned and controlled post-secondary institute.[23]

21st century

In February 2008, Health Canada advised the Council place a precautionary boil-water advisory on all groundwater-fed wells in the Territory. As of March 12, 2019, that advisory was still active.[24]

2020 Railway Protest

In February 2020, Tyendinaga became a focal point for the nationwide protests in solidarity with the hereditary chiefs of the Wetʼsuwetʼen opposing the construction of the Coastal GasLink Pipeline through their territory in central British Columbia. On February 6, members of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation parked several vehicles near (but not on) a level crossing just north of the territory on Wyman Road, causing Via Rail and Canadian National Railway (CNR) to cancel service on vast parts of their network for almost a month.[25][26][27][28] The Ontario Provincial Police decided not to act immediately on several injunctions issued by CNR, but gave the protesters notice on February 23 to clear their encampment by midnight to avoid prosecution for disobeying the injunctions.[29] Ultimately, the protesters did not leave, and the OPP intervened, arresting several protesters on February 24.[30]

Facilities

The main facilities of the reserve are located along York Road, where the band administration building, Quinte Mohawk School, and Kanhiote Public Library are located.

Education

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory is home to First Nations Technical Institute (FNTI), an educational partner with Canadore College, First Nations University of Canada, Humber College, Loyalist College, Queen's University, Ryerson University, St. Lawrence College and Trent University. FNTI course offerings include programs in Aviation (in partnership with the Tyendinaga (Mohawk) Airport), Law, Public Relations, Indigenous Community Health and the Mohawk language.[31]

The Territory also has a primary school, Quinte Mohawk School, which opened in 1974.[32] For secondary school, on-reserve residents have the option of attending East Side Secondary School in Belleville to the west of the Territory, or attending the Ohahase Learning Centre, a private secondary school operated by the First Nations Technical Institute.[33] Ohahase means "new road" in the Mohawk language.[33]

The language group, Tsi Tyonnheht Onkwawenna (TTO), organizes a variety of cultural educational programs, including Mohawk language classes and language documentation.[34] In 2012 TTO was attempting to raise money to found a Mohawk-language immersion primary school (similar to the one operated at Akwesasne, another Mohawk reserve) to be called Kawenna'òn:we.[35]

Transport

The territory is connected to Ontario Highway 401 by Ontario Highway 49 which runs north–south through the reserve, south to Prince Edward. Tyendinaga Mohawk Airfield general aviation airport is located just west of Highway 49, just north of the Bay of Quinte.

Media

A First Nations community-owned radio station, known as KWE, Mohawk Nation Radio operated on a frequency of 105.9 FM until early 2011. It relaunched in June 2012 on 89.5, but subsequently relocated to 92.3 and covers the area from Belleville to Deseronto. The station has no known callsign and has no relation to CKWE-FM, another First Nations community radio station in Maniwaki, Quebec.

Tyendinaga also has a second First Nations community-owned radio station that transmits at 87.9 MHz on the FM dial, known as "Real People’s Radio 87.9 FM".[36]

The community currently does not publish a newspaper of its own.

Population

| Date | Total population | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| May 1784 | 100-125 | [4] |

| August 1836 | 319 | [37] |

| July 1872 | 757 | [38] |

| May 2016 | 2525 | [39] |

References

- "Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory community profile". 2006 Census data. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- Indian and Northern Affairs Canada - First Nation Profiles: Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte Registered Population

- McLeod, Alan (August 30, 2019). DISCUSSION DRAFT The Third Crossing Project Report on Indigenous Consultation (PDF) (Report). Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "History". Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Gary Warrick (2007). "Precontact Iroquoian Occupation of Southern Ontario". In Jordan E. Kerber (ed.). Archaeology of the Iroquois: Selected Readings and Research Sources. Syracuse University Press. pp. 124–163. ISBN 978-0-8156-3139-2.

- Neta Crawford (15 April 2008). "The Long Peace among Iroquois Nations". In Kurt A. Raaflaub (ed.). War and Peace in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 348–. ISBN 978-0-470-77547-9.

- Osborne, Brian S.; Swainson, Donald (2011). Kingston, Building on the Past for the Future. Quarry Heritage Books. p. 19. ISBN 1-55082-351-5.

- Johnston, C.M. (2003) [1983 (revision)]. "DESERONTYON, JOHN". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 5. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved July 12, 2020.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Graymont, Barbara (2003) [1983 (revision)]. "THAYENDANEGEA". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 5. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved July 12, 2020.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Thomas, Earle (2003) [1987 (revision)]. "JOHNSON, Sir JOHN". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 6. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved July 12, 2020.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. The Royal Canadian Geographical Society in conjunction with National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Métis National Council, and Indspire. 2018. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-9867516-6-0.

- Simcoe, John Graves (1 April 1793). Simcoe Deed (Treaty No. 3½).

- "[https://deserontoarchives.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/td-ctlc-culbertson-tract-land-claim-collection.pdf “Proceedings of an Indian Council held at the Mohawk Village in the Bay de Quinté from the 2d to the 10th Sept 1800 on the differences existing among the Indians of that Village” [This called after two of Captain John‟s relatives were killed by the group led by Isaac Hill. The document is a very bad reproduction.] 48pp.]". Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection, ID: TD/CTLC 54. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- "[https://deserontoarchives.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/td-ctlc-culbertson-tract-land-claim-collection.pdf Complaint of John Deserontyon (and also signed Peter John), addressed to Francis Gore, Lieutenant Governor, 14 October 1809, complaining about leases of land to whites for removal of timber. 4pp.]". Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection, ID: TD/CTLC 58. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- "Letter from John Ferguson to William Claus, Deputy Superintendent General, Indian Affairs, 5 March 1819, concerning threats made by Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte to passers-by; the influence of white lumbermen over the Mohawks; lineage (in relation to a General Order on 2 November 1818 that presents should not be given to the descendants of Europeans): “Will not a difficulty arise, as to who these people are? In the Mohawk village here, a large proportion are the immediate (perhaps the second generation) descendants of Germans; there is also a family of immediate descendants of Africans: Are they to be considered as Indians? There are also some descendants of Americans, whose ancestors were Europeans. Will they come within the intention of the Order? In fact there are but few real Indians amongst them.” 4pp.". Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection, ID: TD/CTLC 65. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte v Canada (Federal Court June 18, 2013) ("The applicant alleges that the Crown illegally patented approximately 923 acres of this land, known as the Culbertson Tract in 1837, despite the land having never been surrendered. Over time, various third parties acquired interests in the Culbertson Tract. Approximately 500 acres are now part of the Township of Tyendinaga. The remaining 423 acres comprise approximately 60% of the Town of Deseronto.").Text

- "The Elected Councilmen of 1870". MBQ Research. November 2013. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020 – via Docplayer.

- Hamilton, Michelle A. (November 11, 2020). "Oronhyatekha". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- "Doctor Oronhyatekha: A Mohawk of National Historic Significance" (PDF). Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2020.

- "Chiefs and Councillors - Ontario Region" (PDF). Government of Canada Publications: 278–283. November 11, 1993.

- Belleville Public Library. "Articles relating to the construction of Quinte Mohawk School" (1971-1974) [Text]. Belleville Public Library Subject Files, Box: Box 18, File: Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory Schools, ID: Quinte_Mohawk_School_construction_articles.pdf. Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County.

- "History of FNTI". FNTI. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Boil Water Reminder". Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte. March 12, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Spitters, John (February 7, 2020). "PHOTOS: Tyendinaga protesters stop train traffic". Quinte News. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Mazur, Alexandra (February 10, 2020). "B.C. pipeline protests continue to halt Ontario trains for 5th day in a row". globalnews.ca. Global News. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "VIA Rail Passenger Trains Impacted by Tyendinaga Mohawk Blockade". NetNewsLedger. February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Gallant, Jacques; Hunter, Paul (February 8, 2020). "Protests shut down Ontario rail lines in support of Wetʼsuwetʼen Nation". Toronto Star. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Coletta, Amanda (February 18, 2020). "Why protesters are shutting down Canada's rail service". Washington Post.

- Tunney, Catharine (February 24, 2020). "Police presence remains on Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory after morning arrests". cbc.ca. CBC News. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- McCarty, Teresa L. (2013). Language Planning and Policy in Native America: History, Theory, Praxis. Multilingual Matters. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-1-84769-865-0.

- Belleville Public Library. "Articles relating to the construction of Quinte Mohawk School" (1971-1974) [Text]. Belleville Public Library Subject Files, Box: Box 18, File: Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory Schools, ID: Quinte_Mohawk_School_construction_articles.pdf. Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County.

- "Ohahase Learning Centre". FNTI. 2010-05-27. Archived from the original on 2011-11-27. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- "Mohawk language circle aims to strengthen identity". CBC News : Politics. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- "Primary Immersion | Tsi Tyonnheht Onkwawenna". Tto-kenhteke.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- www.rpr879.com

- "[https://deserontoarchives.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/td-ctlc-culbertson-tract-land-claim-collection.pdf Draft statement of the several Indian tribes in the Province of Upper Canada. Notes that there are 319 Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, in receipt of £450 per annum and owning 100,000 acres, part of which had recently been surrendered. 19 Aug 1836. 3pp.]". Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection, ID: TD/CTLC 131. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- "[https://deserontoarchives.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/td-ctlc-culbertson-tract-land-claim-collection.pdf Census return of Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, July 1872 (757 individuals). Shows name of head of each household, number of male and female adults and children in the household and whether the number in the house had increased or decreased since the previous year. 7pp.]". Catalogue of Culbertson Tract Land Claim documents collection, ID: TD/CTLC 174. Town of Deseronto Archives Department.

- "Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, IRI [Census subdivision], Ontario". Statistics Canada (Table). Aboriginal Population Profile, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

External links

![]() Media related to Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory at Wikimedia Commons