Ural (river)

The Ural (Russian: Урал, pronounced [ʊˈraɫ]), known as Yaik (Russian: Яик, Bashkir: Яйыҡ, romanized: Yayıq, pronounced [jɑˈjɯq]; Kazakh: Жайық, romanized: Jayıq, جايىق, pronounced [ʑɑˈjəq]) before 1775, is a river flowing through Russia and Kazakhstan in the continent border between Europe and Asia. It originates in the southern Ural Mountains and discharges into the Caspian Sea. At 2,428 kilometres (1,509 mi), it is the third-longest river in Europe after the Volga and the Danube, and the 18th-longest river in Asia. The Ural is conventionally considered part of the boundary between the continents of Europe and Asia.

| Ural | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | Kazakhstan, Russia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Ural Mountains |

| Mouth | Caspian Sea |

• coordinates | 46°53′N 51°37′E |

| Length | 2,428 km (1,509 mi) |

| Basin size | 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 400 m3/s (14,000 cu ft/s) |

| Official name | Ural River Delta and adjacent Caspian Sea coast |

| Designated | 10 March 2009 |

| Reference no. | 1856[1] |

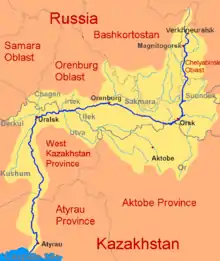

The Ural arises near Mount Kruglaya in the Ural Mountains, flows south parallel and west of the north-flowing Tobol, through Magnitogorsk, and around the southern end of the Urals, through Orsk where it turns west for about 300 kilometres (190 mi), to Orenburg, where the river Sakmara joins. From Orenburg it continues west, passing into Kazakhstan, then turning south again at Oral, and meandering through a broad flat plain until it reaches the Caspian a few miles below Atyrau, where it forms a fine 'digitate' (tree-like) delta.[2]

Geography

The river begins at the slopes of the Kruglaya Mountain[3] of the Uraltau mountain ridge in South Ural, on the territory of the Uchalinsky District of Bashkortostan. There it has an average width of 60 to 80 metres (200 to 260 ft) and flows as a typical mountain river. It then falls into the Yaik Swamp and after exiting it widens up to 5 kilometres (3 mi). Below Verkhneuralsk, its flow is characteristic of a flatland river; there it enters Chelyabinsk and Orenburg Oblasts. From Magnitogorsk to Orsk its banks are steep and rocky and the bottom has many rifts. After Orsk, the river abruptly turns west and flows through a 45-kilometre (28 mi) long canyon in the Guberlinsk Mountains. After Uralsk, it flows from north to south, through the territory of West Kazakhstan Region and Atyrau Region of Kazakhstan. There, the river widens and has many lakes and ducts. Near the mouth, it splits into the Yaik and Zolotoy distributaries[4][5] and forms vast wetlands. The Yaik distributary is shallow, with almost no trees on the shores, and is rich in fish; whereas Zolotoy is deeper and is navigable.[6] Ural River has a spectacular tree-like (or "digitate") shape of the delta (see image). This type of delta forms naturally in the slow rivers which deliver a great deal of sediments and flow into a quiet sea.[2] In the delta, 13.5 kilometres (8.4 mi) from the mouth of the Zolotoy distributary lies Shalyga Island, which is 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) long, with heights of 1 to 2 metres (3 to 7 ft) and maximum widths of 0.3 kilometres (980 ft).[7]

The tributaries, in order going upstream, are Kushum, Derkul, Chagan, Irtek, Utva, Ilek (major, left), Bolshaya Chobda, Kindel, Sakmara, Tanalyk (major, right), Salmys, Or (major, left) and Suunduk.[5]

The entire length of the Ural River is considered the Europe-Asia boundary by most authoritative sources.[8][9][10] Rarely, the smaller, shorter Emba River is claimed as the continental boundary,[11][12] but that pushes "Europe" much further into "Central Asian" Kazakhstan. The Ural River bridge in Orenburg is even labeled with permanent monuments carved with the word "Europe" on one side, "Asia" on the other.[13] Regardless, Kazakhstan has some European territory and is at times included in European political and sports organizations[14][15]

Hydrography

The river is mostly fed by melting snow (60–70%); the contribution of precipitation is relatively minor.[16] Most of its annual discharge (65%) occurs during the spring floods, which occur in March and April near the mouth and in late April through June upstream; 30% drain during the summer and autumn and 5% in winter. During the floods, the river widens to above 10 kilometres (6 mi) near Uralsk and to several tens of kilometers near the mouth. Water level is highest in later April upstream and in May downstream. Its fluctuation is 3 to 4 metres (10 to 13 ft) in the upper stream, 9 to 10 metres (30 to 33 ft) in the middle of the river and about 3 metres (10 ft) in the delta. The average water discharge is 104 cubic metres per second (3,700 cu ft/s) near Orenburg, and 400 cubic metres per second (14,000 cu ft/s) at the Kushum village, which is 76.5 kilometres (47.5 mi) from the mouth. The maximum discharge is 14,000 cubic metres per second (490,000 cu ft/s) and the minimum is 1.62 cubic metres per second (57 cu ft/s). Average turbidity is 280 grams per cubic metre (0.47 lb/cu yd) at Orenburg and 290 grams per cubic metre (0.49 lb/cu yd) near Kushum. The river freezes at the source in early November and in the middle and lower reaches in late November. It opens in the lower reaches in late March and in early April in the upper reaches. The ice drift is relatively short.[3][4][5]

The average depth is 1 to 1.5 metres (3 to 5 ft) near the source, and it increases in the middle reaches and especially near the mouth. The density of underwater vegetation also increases from the source to the mouth, so as the richness of the fauna. The bottom in the upper stream is rocky, with pebble and sand; it changes to silt-sand and occasionally clay downstream. The basin is asymmetrical – its left side from the river is 2.1 times larger in area than the right side; however, the right side is more important for feeding the river. The density of the tributaries is 0.29 km/km2 in the right and 0.19 km/km2 in the left side of the basin. The right-side tributaries are typical mountain rivers whereas the left-side tributaries have flatland character. About 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the mouth there is a dangerous spot for shipping called Kruglovskaya prorva (Russian: Кругловская прорва meaning Kruglovsk abyss). Here the river narrows and creates a strong vortex over a deep pit. The climate is continental with frequent and strong winds. Typical annual precipitation is 530 millimetres (21 in).[6][16]

Fauna

The wetlands at and near the delta of the Ural River are especially important to migrating birds as an important stop-over along the Asian flyway.[2] They host many endemic and endangered species, such as great white pelican, Dalmatian pelican, pygmy cormorant, cattle egret, little egret, greater flamingo, white-headed duck, ferruginous duck, Eurasian spoonbill, glossy ibis, houbara bustard, great black-headed gull, slender-billed gull, squacco heron, common crane, demoiselle crane, slender-billed curlew, black stork, red-breasted goose, lesser white-fronted goose, lesser kestrel, whooper swan, tundra swan, osprey, pallid harrier, short-toed eagle and many others. The pygmy cormorant was observed sporadically before 1999 and more regularly after that. Cattle egret is observed since 1990 between April and September (as most other migratory birds in this area), with the total population of several dozen couples. It feeds on frogs, mollusks and small fish.[17] Upstream, there are more of the resident bird species, such as grouse, wild pigeon and partridge.[6]

Ural River is also important for many fish species of the Caspian Sea which visit its delta and migrate upstream for spawning. In the lower reaches of the river there are 47 species from 13 families. The family Cyprinidae account for 40%, sturgeon and herring make up 11%, perch and herring 9% and salmon 4.4%. The main commercial species are sturgeon, roach, bream, perch, carp, asp and Wels catfish. The rare species include Caspian salmon, sterlet, white salmon and kutum.

In the delta of the river and nearby regions live about 48 animal species belonging to 7 orders; most common are rodents (21 species) and predators (12). Among them, Bobrinski's serotine and marbled polecat are endemic. Key species are raccoon dog, muskrat (appeared recently), European hare, house mouse, brown rat, and wild boar. Wild boars had a density of 1.2–2.5 per hectare in 2000 and are hunted commercially. Others include elk, fox, wolf, dwarf fat-tailed jerboa, great gerbil, northern mole vole and saiga antelope.[6][17] The Turkmenian kulan (Equus hemionus kulan) used to live at the Ural River. It might be extinct from that region.

|

|

|

| Great gerbil | Marbled polecat | Sturgeon |

The reptiles are represented by bog turtles, common water snakes, rat snakes and sand lizard. Bog turtles are found in all waters. Common water snakes live on the banks of canals. Rat snakes and sand lizards are few and inhabit relatively high areas of land. Two more reptiles, Caspian whipsnake and Coluber spinalis, are extremely rare. Among amphibians common are lake frog and green frog.[17]

With an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 species, insects exceed all other animals of the region by diversity and biomass. Terrestrial and aquatic insects make up a significant proportion of the diet of birds. Many species are parasitic on birds and transmit infection. Other dominating inhabitants of the river are protozoa, rotifers, Cladocera and copepods. Mollusks are mostly represented by gastropods and bivalves.[17]

Industry

Water from the upper reaches of the Ural River is used to supply the prominent Magnitogorsk (Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, built in the early 1930s) and Orsk-Khalilovsk metallurgical plants, and the low reaches are used for irrigation. Two reservoirs were created near Magnitogorsk, and there is a hydroelectric plant near the village of Iriklinskaya with the corresponding reservoir. Below Uralsk, there is another reservoir and the Kushumsky channel. The river is navigated up to Uralsk and there is a port in Atyrau.[3][18] Fishery is well developed; the commercial fish species include sturgeon, perch, herring, bream, carp and catfish.[5] The delta of Ural River accounts for about half of the fish catchment in Kazakhstan.[17] Also widespread is agriculture, especially growth of melons and watermelons. The city of Atyrau is a major oil producing center of Kazakhstan.[6]

Etymology

The river was called Δάϊκος (Daïkos) by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD.[19][20] Yulian Kulakovsky reads this as Turkic "Jajyk" or "Яик" and on this basis identifies the Huns as Turkic speakers.[21] However, Gerard Clauson disputes that the name could be of Turkic origin as early as the 2nd century, and instead attributes it to Sarmatian origin.[22] The name Яйыҡ (Yayıq) is currently used in the Bashkir language and Жайық (Zhayıq) in Kazakhstan. In later European texts it is sometimes mentioned as Rhymnus fluvius[23] and in the Russian chronicle of 1140 as Yaik.[24] The river was renamed Ural in the Russian language in 1775, by Catherine II of Russia.

History

In the 10th to 16th centuries, the city of Saray-Jük (or Saraichik, meaning "small Sarai") on the Ural River (now in Atyrau Province of Kazakhstan) was an important trade center on the Silk Road. In the 13th century, it became a stronghold of the Golden Horde. It was destroyed in 1395 by the army of Timur but then rebuilt to become the capital of Nogai Horde in the 15th and 16th centuries. It was finally reduced to a village in 1580 by the Ural Cossacks.[6][25]

After the Russian conquest of the Ural basin in the late 16th century, the shores of the Ural became home to the Yaik Cossacks. One of their main activities was fishing for the sturgeon and related fishes (including the true sturgeon, starry sturgeon, and beluga) in the Ural River and the Caspian. A great variety of fishing techniques existed; the most famous of them was bagrenye (Russian: багренье, from bagor Russian: багор, meaning pike pole): spearing hibernating sturgeons in their underwater lairs in mid-winter. The bagrenye was allowed only on one day of the year. On the appointed day, a large number of Cossacks with pike poles were gathering on the shore; after a signal was given, they rushed on the ice, broke it with their poles, and speared and pulled the fish. Another fishing technique was constructing a weir, known as the uchug (учуг) across the river, to catch fish going upstream to spawn. Until 1918, an uchug was set up in the summer and autumn near Uralsk, so that the fish would not go upstream beyond the Cossacks' land. While the uchug weirs were also known in the Volga Delta, the bagrenye was thought to be a uniquely Ural technique.[26][27]

The Ural Cossacks (known originally as the Yaik Cossacks) resented the attempts by the central government to impose rules and regulations on them, and on occasions rose in rebellions. The largest rebellion, the Pugachev's Rebellion of 1773–75, involved not only the Ural, but much of south-eastern Russia, and resulted in a loss of the government control there. After its suppression, Empress Catherine issued a decree of 15 January 1775 to rename most of the places involved in the revolt, in order to erase the memory of it. Thus the Yaik River and the city of Yaitsk were renamed to the Ural River and Uralsk, respectively, and the Yaik Cossacks became the Ural Cossacks.[28]

(.. for the complete oblivion of this unfortunate event that occurred on the Yaik, the Yaik river, whose name the [Cossack] Host and the city have previously borne, shall be renamed the Ural, as the aforesaid river has its source in the Ural Mountains; therefore, the [Cossack] Host shall be named the Ural [Cossack] Host, and shall not be called the Yaik [Cossack] Host; similarly, Yaitsk City shall be henceforth called Uralsk.)

References

- "Ural River Delta and adjacent Caspian Sea coast". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Ural River Delta, Kazakhstan (NASA Earth Observatory)

- Ural River, Encyclopædia Britannica

- V. A. Balkov. Ural (in Russian). bashedu.ru

- "Ural River" (in Russian). Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- 800 km on Ural River (in Russian)

- Zonn, p. 375

- National Geographic Atlas of the World (9th ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic. 2011. ISBN 978-1-4262-0633-7. "Europe" (plate 59); "Asia" (plate 74): "A commonly accepted division between Asia and Europe ... is formed by the Ural Mountains, Ural River, Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and the Black Sea with its outlets, the Bosporus and Dardanelles."

- World Factbook. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency.

- Klement Tockner; Urs Uehlinger; Christopher T. Robinson (2009). "18". Rivers of Europe (Illustrated ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 9780123694492.

- Glanville Price (2000). Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 12. ISBN 0-631-22039-9.

- Zonn, p. 178

- "Orenburg bridge monument photos". katjasdacha.com.

- Progress aplenty in Kazakhstan, uefa.com

- Why Europe plays against Asians (in Russian). sport.ua (2008-09-10)

- Ural River chelindustry.ru (in Russian)

- Фауна: Дельта реки Урал и прилегающее побережье Каспийского моря. wetlands.kz. (Fauna of the delta of Ural River, in Russian)

- Zonn, p. 45

- Ptolemy, Claudius (1843). "Book VI, chapter 14. Σκυθίας τῆς ἐντὸς Ἰμάου ὄρους θέσις". In Nobbe, Karl Friedrich August (ed.). Geographia (in Greek). Leipzig: Karl Tauchnitz. p. vol. 2, p. 122.

- McCrindle, John Watson (1885). Ancient India as Described by Ptolemy. Bombay: Thacker, Spink. p. 290.

Rhymmos.

- Yu. Kulakovsky. "Chapter 2. The map of European Sarmatia" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- Clauson, Gerard (2005). Studies in Turkic and Mongolic Linguistics (rev. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 75–76, 124. ISBN 9781134430123.

- Philippus Ferrarius; Michel-Antoine Baudrand (1738). Novum lexicon geographicum: in quo universi orbis, urbes, regiones ... flumina novis & antiquis nominibus appellata, suisque distantiis descripta recensetur (in Latin). p. 109.

- B.A. Rybakov (1972). Русские летописцы и автор Слова о полку Игореве (in Russian). Nauka.

- Paul Brummell (2008). Bradt Kazakhstan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-84162-234-7.

- Zonn, p. 416

- ""Багренье" (Bagrenye, i.e. Pike-pole fishing)". Энциклопедический лексикон (Encyclopedic lexicon) (in Russian). vol. 4. Saint Petersburg. 1835. p. 65.

- A.I. Poterpeeva & V.E. Chetin (1980). Revoliutsionnaia i trudovaia letopis Iuzhnouralskogo kraia: 1682–1918. South Ural.

Bibliography

- Zonn, Igor S.; Kostianoy, Andrey & Kosarev, Aleksey N. (2010). The Caspian Sea Encyclopedia. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-11523-3.