Marbled polecat

The marbled polecat (Vormela peregusna) is a small mammal belonging to the monotypic genus Vormela within the mustelid subfamily Ictonychinae. Vormela is from the German word Würmlein, which means "little worm". The specific name peregusna comes from perehuznya (перегузня), which is Ukrainian for "polecat". Marbled polecats are generally found in the drier areas and grasslands of southeastern Europe to western China. Like other members of Ictonychinae, it can emit a strong-smelling secretion from anal sacs under the tail when threatened.

| Marbled polecat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Vormela Blasius, 1884 |

| Species: | V. peregusna |

| Binomial name | |

| Vormela peregusna (Güldenstädt, 1770) | |

| |

| Marbled polecat range | |

Description

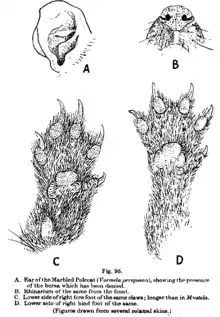

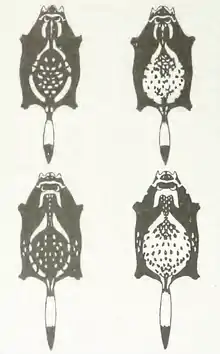

Ranging in length from 29–35 cm (head and body), the marbled polecat has a short muzzle and very large, noticeable ears. The limbs are short and claws are long and strong. While the tail is long, with long hair, the overall pelage is short. Black and white mark the face, with a black stripe across the eyes and white markings around the mouth. Dorsally, the pelage is yellow and heavily mottled with irregular reddish or brown spots. The tail is dark brown with a yellowish band in the midregion. The ventral region and limbs are a dark brown. Females weigh from 295 to 600 g, and males can range from 320 to 715 g.

Distribution

The marbled polecat is found from southeast Europe to Russia and China. Its range includes Bulgaria, Georgia, Turkey, Romania, Asia Minor, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestinian Territories, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Afghanistan, north-western Pakistan, Yugoslavia, Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan, North-Siberian Altai steppes. In 1998, a marbled polecat was recorded on the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt.

Behavior

Marbled polecats are most active during the morning and evening. Their eyesight is weak and they rely on a well-developed sense of smell. Vocalization is limited and consists of shrill alarm cries, grunts and a submissive long shriek.

Marbled polecats are solitary and move extensively through their 0.5- to 0.6-km2 home range. They generally only stay in a shelter once. When they encounter each other, they are usually aggressive.

When alarmed, a marbled polecat will raise up on its legs while arching its back and curling its tail over the back, with the long tail hair erect. It may also raise its head, bare its teeth, and give shrill, short hisses. If threatened, it can expel a foul-smelling secretion from enlarged anal glands under the tail.

To dig, such as when excavating dens, the marbled polecat digs out earth with its forelegs while anchoring itself with its chin and hind legs. It will use its teeth to pull out obstacles such as roots.

Reproduction

Marbled polecats mate from March to early June. Their mating calls are most often heard as low rumbling sounds in a slow rhythm. Gestation can be long and variable (243 days to 327 days). Parturition has been observed to occur from late January to mid-March. Delayed implantation allows marbled polecats to time the birth of their cubs for favorable conditions, such as when prey is abundant.

Litter sizes range from four to eight cubs. Only females care for the young. Cubs open their eyes at around 38–40 days old, are weaned at 50–54 days and leave their mother (disperse) at 61–68 days old.

Ecology

Habitat

Marbled polecats are found in open desert, semidesert, and semiarid rocky areas in upland valleys and low hill ranges, steppe country and arid subtropical scrub forest. They avoid mountainous regions. Marbled polecats have been sighted in cultivated areas such as melon patches and vegetable fields.

Burrows of large ground squirrels or similar rodents such as the great gerbil (Rhombomys opinus) and Libyan jird are used by marbled polecats for resting and breeding. They may also dig their own dens or live in underground irrigation tunnels. In the winter, marbled polecats will line their dens with grass.

Diet

Marbled polecats are known to eat ground squirrels, Libyan jirds (Meriones libycus), Armenian hamsters (Cricetulus migratorius), voles, mole rats (Spalax lecocon ehrenbergi), house mice (Mus musculus), and other rodents, small hares, birds, lizards, fish, frogs, snails, and insects (beetles and crickets), as well as fruit and grass. They are also recorded as taking small domestic poultry such as chickens and pigeons, as well as stealing smoked meat and cheese.

Conservation status

In 2008, V. peregusna was classified as a vulnerable species in the IUCN Red List due to a population reduction of at least 30% in the previous 10 years. In 1996, it had been considered a species of least concern. The decline in marbled polecat populations thought to be due to habitat destruction (cultivation) and reduction in available prey by use of rodenticides.

In Pakistan, it is listed as an endangered species.

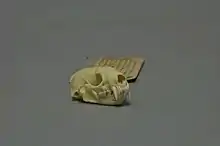

From a research done on the Marbled Polecat, data revealed that from the West to the East, there was a gradual decrease in morphological diversity of the polecat skulls. Thus giving us Western and Eastern as a factor to diversify the polecats. Also, the data related to the range formation of the species rather than climate change.[2]

Relation with humans

The marbled polecat was once sought for its fur, generally known as "fitch" or more specifically, "perwitsky" in the fur trade.[3][4]

In 1945, Kabul shopkeepers were reported to have kept marbled polecats to exterminate rodents. Their journals also show some developed an adverse reaction to the strong smell they emit when threatened. Side effects varied from fever to diarrhea.

Other names for the marbled polecat include aladzhauzen (Turkmen), berguznya (Kuban), chokha (Kalmuck), fessyah ("stinky" in Arabic), abulfiss (Arabic), hǔ-yòu (Chinese 虎鼬, lit. ‘tiger musteline’), myshovka (Terek Cossacks dialect), pereguznya, pereguzka, or perevishchik (Ukrainian), perevyazka (Russian), perewiaske (Polish), khaytakis (Armenian), alaca sansar, alaca kokarca, benekli kokarca (Turkish), suur-tyshkan (Kyrgyz), putois marbré or putois de Pologne (French); Tigeriltis (German, lit. ‘tiger polecat’), mottled polecat (English), sarmatier; Syrian marbled polecat, and tiger polecat. In some contexts it is called the tiger weasel.[5][6]

Subspecies

The subspecies of V. peregusna include:

- V. p. alpherakyi

- V. p. euxina

- V. p. negans

- V. p. pallidor

- V. p. peregusna

- V. p. syriaca

References

- Abramov, A.V.; Kranz, A. & Maran, T. (2016). "Vormela peregusna". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T29680A45203971.

- Puzachenko, Andrey Yu; Abramov, Alexei V.; Rozhnov, Viatcheslav V. (March 2017). "Cranial variation and taxonomic content of the marbled polecat Vormela peregusna (Mustelidae, Carnivora)". Mammalian Biology. 83: 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2016.11.007.

- "Dictionary definition". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Peterson, Marcus (1914). The fur traders and fur bearing animals. Hammond Press. p. 191.

"Fitch" was a popular fur with our grandmothers, and at present has come back into favor. [...] The Perwitsky or Sarmatian Mottled Polecat (Putorius sarmaticus), is a distinct species...

- Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, the late M.S., eds. (2003). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 282. ISBN 9788120815964.

- Goodwin, George Gilbert (1954). "tiger+weasel" The Animal Kingdom: Mammals. Doubleday. p. 508.

Notes

- ^ Akhtar, S. A. (1945). "On the habits of the marbled polecat, Vormela peregusna". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 45: 412.

- ^ Bodenheimer, F.S. (1935). Animal life in Palestine: an introduction to the problems of animal ecology and zoogeography. Jerusalem, Israel: L. Mayer.

- ^ Ben-David, M. (1988). The biology and ecology of the Marbled polecat, Vormela peregusna syriaca, in Israel. Israel: Tel-Aviv University.

- ^ Ben-David, M. (1998). "Delayed implantation in the marbled polecat, Vormela peregusna syriaca (Carnivora, Mustelidae): evidence from mating, parturition, and post-natal growth". Mammalia. 62 (2): 269–283. doi:10.1515/mamm.1998.62.2.269. S2CID 85368948.

- ^ Gorsuch, W.; Larivière, Serge (2005). "Vormela peregusna". Mammalian Species. 779: 1–5. doi:10.1644/779.1.

- ^ Harrison, D. (1968). Mammals of Arabia Volume 2. London: Ernest Benn Limited.

- ^ Kryštufek, B. (2000). "Mustelids in the Balkans – small carnivores in the European biodiversity hot-spot.". In H. J. Griffiths (ed.). Mustelids in a modern world: management and conservation aspects of small carnivore and human interactions. Leiden, Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers. pp. 281–294.

- ^ Lewis, R. E.; J. H. Lewis & S. I. Atalla (1968). "A review of Lebanese mammals: Carnivora, Pinnipedia, Hyracoidea, and Artiodactyla". Journal of Zoology London. 154 (4): 517–531. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1968.tb01683.x.

- ^ MacDonald, D.; Barrett, P. (1993). Mammals of Britain and Europe. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-00-219779-0.

- ^ Milenković, M.; M. Pavnović; H. Abel; H. J. Griffiths (2000). "The marbled polecat, Vormela peregusna (Güldenstaedt 1770) in FR Yugoslavia and elsewhere". In H. J. Griffiths (ed.). Mustelids in a modern world: management and conservation aspects of small carnivore and human interactions. Leiden, Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers. pp. 321–329.

- ^ Novikov, G.A. (1962). Carnivorous mammals of the fauna of the USSR. Jerusalem: Israeli Program of Scientific Translation. ISBN 0-7065-0169-1.

- ^ Özkurt, Ş.; M. Sözen; N. Yiğit & E. Çolak (1999). "A Study on Vormela peregusna Guldenstaedt, 1770 (Mammalia: Carnivora) in Turkey" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Zoology. 23: 141–144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2006-04-08.

- ^ Qumsiyeh, M. B.; Z. S. Amr & D. M. Shafei (1993). "Status and conservation of carnivores in Jordan". Mammalia. 57: 55–62. doi:10.1515/mamm.1993.57.1.55. S2CID 85376882.

- ^ Rifai, L. B.; D. M. Al Shafee; W. N. Al Melhim & Z. S. Amr (1999). "Status of the marbled polecat, Vormela peregusna (Gueldenstaedt, 1770) in Jordan". Zoology in the Middle East. 17: 5–8. doi:10.1080/09397140.1999.10637764.

- ^ Roberts, T.J. (1977). The mammals of Pakistan. England: Ernest Benn Limited. ISBN 0-19-579568-7.

- ^ Saleh, M. A. & M. Basuony (1998). "A contribution to the mammalogy of the Sinai Peninsula". Mammalia. 62 (4): 557–575. doi:10.1515/mamm.1998.62.4.557. S2CID 84960581.

- ^ Schreiber, A.; Wirth, R.; Riffel, M.; van Rompaey, H. (1989). Weasels, civets, mongooses and their relatives: an action plan for the conservation of mustelids and viverrids. Broadview, Illinois: Kelvyn Press, Inc.

- ^ Stroganov, S.U. (1969). Carnivorous mammals of Siberia. Jerusalem, Israel: Israeli Program of Scientific Translation. ISBN 0-7065-0645-6.

- ^ Tikhonov, A., Cavallini, P., Maran, T., Krantz, A., Herrero, J., Giannatos, G., Stubbe, M., Conroy, J., Kryštufek, B., Abramov, A. & Wozencraft, C. 2008. Vormela peregusna. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 16 February 2011.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Vormela peregusna. |