Yamnaya culture

The Yamnaya culture, also known as the Yamnaya Horizon,[2] Yamna culture, Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic steppe), dating to 3300–2600 BC.[3] Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: Ямная (romanization: yamnaya) is a Russian adjective that means 'related to pits (yama)', and these people used to bury their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers. "Yamna" is the name that is derived from the same word in Ukrainian (ямна, romanization: yamna).

| |

| Alternative names |

|

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Eurasia |

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 3300–2600 BC |

| Preceded by | Samara culture, Khvalynsk culture, Dnieper–Donets culture, Sredny Stog culture, Repin culture, Maykop culture |

| Followed by |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The people of the Yamnaya culture were likely the result of a genetic admixture between the descendants of Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers[lower-alpha 1] and people related to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus.[4] People with this ancestral component are known as Western Steppe Herders.[5] Their material culture was very similar to the Afanasevo culture, and the populations of both cultures are genetically indistinguishable.[1] They lived primarily as nomads, with a chiefdom system and wheeled carts that allowed them to manage large herds.

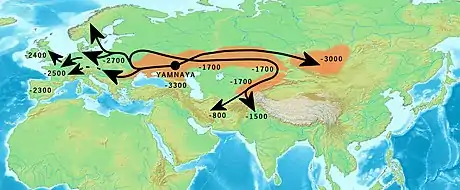

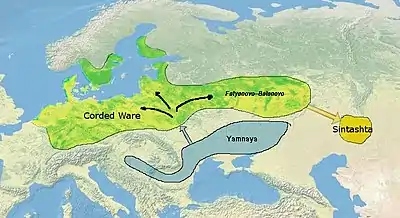

They are also closely connected to Final Neolithic cultures, which later spread throughout Europe and Central Asia, especially the Corded Ware people and the Bell Beaker culture, as well as the peoples of the Sintashta, Andronovo, and Srubnaya cultures. Back migration from Corded Ware also contributed to Sintashta and Andronovo.[6] In these groups, several aspects of the Yamnaya culture are present.[lower-alpha 2] Genetic studies have also indicated that these populations derived large parts of their ancestry from the steppes.[1][7][8][9]

The Yamnaya culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans, and is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language.

Origins

| Origins of Yamnaya culture |

|---|

Sredny Stog culture (v.4500-3500 BCE) |

Usatovo culture (c. 3500–3000 BCE) |

Khvalynsk culture (c. 4900–3500 BCE) |

Location of early Yamnaya culture (3400 BCE), according to Anthony (2007) |

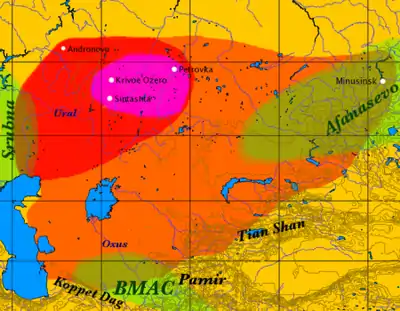

According to Mallory (1999), "The origin of the Yamnaya culture is still a topic of debate," with proposals for its origins pointing to both Khvalynsk and Sredny Stog.[13] The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE)[14] (middle Volga) and the Don-based Repin culture (ca.3950–3300 BCE)[15] in the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe, and the closely related Sredny Stog culture (c. 4500–3500 BCE) in the western Pontic-Caspian steppe, preceded the Yamnaya culture (3300–2500 BCE).[16][17]

According to Anthony (2007), the Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BCE) originated in the Don–Volga area at ca. 3400 BCE,[18][3] preceded by the middle Volga-based Khvalynsk culture and the Don-based Repin culture (c. 3950–3300 BC),[15][3] arguing that late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamnaya pottery.[19] Earlier continuity from eneolithic but largely hunter-gatherer Samara culture and influences from the more agricultural Dnieper–Donets II are apparent.

Alternatively, Parpola (2015) relates both the Corded ware culture and the Yamnaya culture to the late Tripolye culture.[20] He hypothesizes that "the Tripolye culture was taken over by PIE speakers by c. 4000 BCE,"[21] and that in its final phase the Tripolye culture expanded to the steppes, morphing into various regional cultures which fused with the late Sredny Stog pastoralist cultures. This gave rise to the Yamnaya culture.[22]

According to Anthony (2007), the early Yamnaya horizon spread quickly across the Pontic–Caspian steppes between c. 3400 and 3200 BC:[18]

The spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic–Caspian steppes.[23]

[...] The Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes.[24]

According to Pavel Dolukhanov (1996) the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various local Bronze Age cultures, representing "an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures", which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.[25]

In its western range, it was succeeded by the Catacomb culture (2800–2200 BC); in the east, by the Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BC) at the middle Volga. These two cultures were followed by the Srubnaya culture (18th–12th century BC).

Characteristics

Proto-Indo-European

The Yamnaya culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas. It is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, along with the preceding Sredny Stog culture, now that archaeological evidence of the culture and its migrations has been closely tied to the evidence from linguistics[26] and genetics.[7][27] Significantly, there were animal grave offerings,[lower-alpha 3] a feature associated with Proto-Indo-Europeans.[28] The culture was predominantly nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers and a few hillforts.[29] Characteristic for the culture are the burials in pit graves under kurgans (tumuli). The dead bodies were placed in a supine position with bent knees and covered in ochre. Multiple graves have been found in these kurgans, often as later insertions. The earliest remains in Ukraine of a wheeled cart were found in the "Storozhova mohyla" kurgan[lower-alpha 4] associated with the Yamnaya culture.

Recent studies indicate that the Yamnaya people played a role in the domestication of the modern horse.[30]

Archaeogenetics

According to Jones et al. (2015) and Haak et al. (2015), autosomic tests indicate that the Yamnaya people were the result of a genetic admixture between two different hunter-gatherer populations: distinctive "Eastern European hunter-gatherers" (also known as "Eastern Hunter-Gatherers" or "EHG") with high affinity to the Mal'ta–Buret' culture or other, closely related people from Siberia[7] and a population of "Caucasus hunter-gatherers" (CHG) who probably arrived from the Caucasus.[31][4] Each of those two populations contributed about half the Yamnaya DNA.[8][4] According to co-author Andrea Manica of the University of Cambridge:

The question of where the Yamnaya come from has been something of a mystery up to now ... we can now answer that, as we've found that their genetic make-up is a mix of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and a population from this pocket of Caucasus hunter-gatherers who weathered much of the last Ice Age in apparent isolation.[4]

Several genetic studies performed since 2015 have given support to the Kurgan theory of Marija Gimbutas regarding the Proto-Indo-European homeland – that Indo-European languages spread throughout Europe from the Eurasian steppes and that the Yamnaya culture were Proto-Indo-Europeans. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia), would have expanded from the Pontic–Caspian steppes, along with the Indo-European languages. They also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, presumably along with North-Western Indo-European dialects in the Bronze Age.[1][7][8]

Recent studies display genetic continuity between the paternal lineages of the Dnieper-Donets culture and the Yamnaya culture, as the males of both cultures have been found to have been mostly carriers of R1b, and to a lesser extent I2. While the mtDNA of the Dnieper-Donets people is exclusively types of U, which is associated with the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) of Eastern Europe and the Western Hunter Gatherers (WHGs) of Western Europe, the mtDNA of the Yamnaya also includes types frequent among Caucasian Hunter-Gatherers (CHGs) and Early European Farmers (EEFs). This admixture is referred to as Western Steppe Herder (WSH), and has earlier been found among the Sredny Stog culture and the Khvalynsk culture, who preceded the Yamnaya culture on the Pontic–Caspian steppe. Unlike their Khvalynsk predecessors, however, the Y-DNA of the Yamnaya is exclusively of EHG and WHG origin. This suggests that the leading clans of the Yamnaya were of EHG and WHG paternal origin.[32] Admixture between EHGs and CHGs is believed to have occurred on the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe starting around 5,000 BC, while admixture with EEFs happened in the southern parts of the Pontic-Caspian steppe sometime later. As Yamnaya Y-DNA is exclusively of the EHG and WHG type, the admixture appears to have occurred predominately between EHG males, and CHG and EEF females. According to David W. Anthony, this implies that the Indo-European languages were the result of "a dominant language spoken by EHGs that absorbed Caucasus-like elements in phonology, morphology, and lexicon." (spoken by CHGs)[33]

Eastern European hunter-gatherers

According to Haak et al. (2015), "Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers" (EHG) in today's Russia had a high genetic affinity to a c. 24,000-year-old Siberian from Mal'ta–Buret' culture, which in turn resembles other remains of Siberia,[34] such as the Afontova Gora.[7][4] Remains of the "Eastern European hunter-gatherers" have been found in Mesolithic or early Neolithic sites in Karelia and Samara Oblast, Russia, and put under analysis. Three such hunter-gathering individuals of the male sex have had their DNA results published. Each was found to belong to a different Y-DNA haplogroup: R1a, R1b, and J.[8]

Near East population

The Near East population were most likely hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG),[31] though one study suggested that farmers with a CHG component dated to the Chalcolithic era in what is now Iran may be a better fit for the Yamnaya's Near Eastern descent.[35]

Jones et al. (2015) analyzed genomes from males from western Georgia, in the Caucasus, from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (13,300 years old) and the Mesolithic (9,700 years old). These two males carried Y-DNA haplogroup: J* and J2a. The researchers found that these Caucasus hunters were probably the source of the Near Eastern DNA in the Yamnaya.[4] Their genomes showed that a continued mixture of the Caucasians with Middle Eastern took place up to 25,000 years ago, when the coldest period in the last Ice Age started.[4]

An analysis carried out by Gallego-Llorente et al. (2016), concludes that Iranian populations are not a likelier source of the 'southern' component in the Yamnaya than Caucasus hunter-gatherers.[36]

Genetic relationship with the Catacomb culture

A genetic study published in August 2014 examined the DNA of the remains of a number of individuals from the Yamnaya culture and the Catacomb culture, who succeeded the Yamnaya culture as the dominant force on the Pontic steppe. Catacomb people were found to have much higher frequencies of the maternal haplogroups U5 and U4 than people of the Yamnaya culture. Haplogroups U5 and U4 are typical of Western Hunter-Gatherers and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers. A generic similarity between Catacomb people and northern hunter-gatherers, particularly the people of the Pitted Ware culture of southern Scandinavia, was detected. It was suggested that the Catacomb people and the Yamnaya people were not as genetically admixed as previously believed. Interestingly, the modern population of Ukraine was found to be more closely related to people of the Yamnaya culture than people of the Catacomb culture.[37]

Haplogroups

Haplogroup R1b is the most common Y-DNA haplogroup found among both the Yamnaya and modern-day Western Europeans.[1][7]

Mathieson (2015) analyzed twelve individuals ascribed to the Yamna culture. Eleven belonged to haplogroup R1b, specifically to the R1b-L23 subclade, while one belonged to haplogroup I2a2a1b1b.[8]

Mathieson (2018) analysed a Yamnaya male in Bulgaria. He carried haplogroup I2a2a1b1b.[38]

Wang (2019) analyzed four Yamnaya individuals from the Caucasus. One male carried the paternal R1b1a1a2. With regards to mtDNA, three carried U5a1 or subclades of it, while one carried T2a1.[39]

Physical characteristics

Examination of physical remains of the Yamnaya people has determined that they were Europoid, tall, and massively built. Their cephalic index varies depending on the region, with brachycephaly being prevalent in its southern and southeastern areas, and dolichocephaly being prevalent in its northeastern areas.[lower-alpha 5]

The genetic basis of a number of physical features of the Yamnaya people were ascertained by the ancient DNA (aDNA) studies conducted by Haak et al. (2015), Wilde et al. (2014) and Mathieson et al. (2015): They were genetically tall (phenotypic height is determined by both genetics and environmental factors), overwhelmingly dark-eyed (brown), dark-haired and had a skin colour that was moderately light, though somewhat darker than that of the average modern European.[8][41] Despite their pastoral lifestyle, there was little evidence of lactase persistence.[7]

Yamnaya-related migrations

Western Europe

* 3000 BC: Initial eastward migration initiating the Afanasievo culture, possibly Proto-Tocharian.

* 2900 BC: North-westward migrations carrying Corded Ware culture, transforming into Bell Beaker; according to Anthony, westward migration west of Carpatians into Hungary as Yamnaya, transforming into Bell Beaker, possibly ancestral to Italo-Celtic (disputed).

* 2700 BC: Second eastward migration starting east of Carpatian mountains as Corded Ware, transforming into Fatyanovo-Balanova (2800 BCE) → Abashevo (2200 BCE) → Sintashta (2100–1900 BCE) → Andronovo (1900–1700 BCE) → Indo-Aryans.

Haak et al. (2015) conducted a genome-wide study of 69 ancient skeletons from Europe and Russia. They concluded that Yamnaya autosomal characteristics are very close to the Corded Ware culture people, with an estimated 73% ancestral contribution from the Yamnaya DNA in the DNA of Corded Ware skeletons from Germany. The same study estimated a (38.8–50.4 %) ancestral contribution of the Yamnaya in the DNA of modern Central, and Northern Europeans, and an 18.5–32.6 % contribution in modern Southern Europeans; this contribution is found to a lesser extent in Sardinians (2.4–7.1 %) and Sicilians (5.9–11.6 %).[44][27][9] Haak et al. also note that their results state that haplogroup R-M269 spread into Europe from the East after 3000 BC.[45] Studies that analysed ancient human remains in Ireland and Portugal support the thesis that R-M269 was introduced in these places along with autosomal DNA from the Eastern European steppes.[46][47]

Autosomal tests also indicate that the Yamnaya are the most likely vector for "Ancient North Eurasian" admixture into Europe.[7] "Ancient North Eurasian" is the name given in literature to a genetic component that represents descent from the people of the Mal'ta–Buret' culture[7] or a population closely related to them. That genetic component is visible in tests of the Yamnaya people[7] as well as modern-day Europeans, but not of Europeans predating the Bronze Age.[48]

Eastern Europe and Finland

In the Baltic, Jones et al. (2017) found that the Neolithic transition – the passage from a hunter-gatherer economy to a farming-based economy – coincided with the arrival en masse of individuals with Yamnaya-like ancestry. This is different from what happened in Western and Southern Europe, where the Neolithic transition was caused by a population that came from the Near East, with Pontic steppe ancestry being detected from only the late Neolithic onward.[49]

Per Haak et al. (2015), the Yamnaya contribution in the modern populations of Eastern Europe ranges from 46.8% among Russians to 42.8% in Ukrainians. Finland has one of the highest Yamnaya contributions in all of Europe (50.4%).[50][lower-alpha 6]

Central and South Asia

Studies also point to the strong presence of Yamnaya descent in the current nations of South Asia, especially in groups that are referred to as Indo-Aryans.[43][51]

According to Pathak et al. (2018), the "North-Western Indian & Pakistani" populations (PNWI) showed significant Middle-Late Bronze Age Steppe (Steppe_MLBA) ancestry along with Yamnaya Early-Middle Bronze Age (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry, but the Indo-Europeans of Gangetic Plains and Dravidian people only showed significant Yamnaya (Steppe_EMBA) ancestry and no Steppe_MLBA. The study also noted that ancient south Asian samples had significantly higher Steppe_MLBA than Steppe_EMBA (or Yamnaya). The study infers, "The Rors stand out in South Asia as the population with the highest proportion of Steppe ancestry".[51]

Lazaridis et al. (2016) notes "The demographic impact of steppe related populations on South Asia was substantial, as the Mala, a south Indian population with minimal ANI (Ancestral North Indian) along the 'Indian Cline' of such ancestry is inferred to have a minimum~ 18 % steppe-related ancestry, while the Kalash of Pakistan are inferred to have ~ 50 % steppe-related ancestry."[52] Lazaridis et al.'s 2016 study estimated (6.5–50.2 %) steppe related admixture in South Asians.[53][lower-alpha 7]

Lazaridis et al. (2016) further notes that "A useful direction of future research is a more comprehensive sampling of ancient DNA from steppe populations, as well as populations of central Asia (east of Iran and south of the steppe), which may reveal more proximate sources of the ANI than the ones considered here, and of South Asia to determine the trajectory of population change in the area directly."[53]

According to Unterländer et al. (2017), Iron Age Scythians from the southern Ural region, East Kazakhstan and Tuva can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian component, the latter occurring at only trace levels – if at all – among earlier steppe inhabitants.[54]

According to Narasimhan et al. (2019), the Yamnaya-related ancestry, termed Western_Steppe_EMBA, that reached central and south Asia was not the initial expansion from the steppe to the east, but a secondary expansion that involved a group possessing ~67% Western_Steppe_EMBA ancestry and ~33% ancestry from the European cline. This group included people similar to that of Corded Ware, Srubnaya, Petrovka, and Sintashta. Moving further east in the central steppe, it acquired ~9% ancestry from a group of people that possessed West Siberian Hunter Gatherer ancestry, thus forming the Central Steppe MLBA cluster, which is the primary source of steppe ancestry in South Asia, contributing up to 30% of the ancestry of the modern groups in the region.[43]

Artifacts

- From the Hermitage Museum collections

Corded ware pot

Corded ware pot

See also

Notes

- The Eastern European hunter-gatherers were themselves mostly descended from ancient North Eurasians, related to the palaeolithic Mal'ta–Buret' culture.

- Yamnayan cultural aspects, for example, were horse-riding, burial styles, and to some extent the pastoralist economy.

- The animal grave offerings made were cattle, sheep, goats and horses.

- The "Storozhova mohyla" site is near Dnipro, Ukraine, and was excavated by A.I. Trenozhkin.

- "[M]assive broad-faced proto-Europoid type is a trait of post-Mariupol’ cultures, Sredniy Stog, as well as the Pit-grave culture of the Dnieper’s left bank, the Donets, and Don. The features of this type are somewhat moderated in the western part of the steppe ... The Pit-grave culture population of the northeastern part of the Pontic steppes had long heads and narrow faces ... On the Volga and in the Caspian region there is a brachycephalic type of which there are no traces in the Ukraine. All the anthropological types of the Pit-grave culture population have indigenous roots ... The heir of the Neolithic Dnieper-Donets and Sredniy Stog cultures was the Pit-grave culture. Its population possessed distinct Europoid features, was tall, with massive skulls. The second component were the descendants of those buried in the Eneolithic cemetery of Khvalynsk. They are less robust."[40]

- Per Haak et al. (2015), adding a north-Siberian people as a fourth reference population improves residuals for northeastern European populations. This accounts for the higher than expected Yamnaya contribution and brings it down to expected levels (67.8–50.4 % in Finns, 64.9–46.8 % in Russians).

- Lazaridis et al. (2016) Supplementary Information, Table S9.1: "Kalash – 50.2 %, Tiwari Brahmins – 44.1 %, Gujarati (four samples) – 46.1 % to 27.5 %, Pathan – 44.6 %, Burusho – 42.5 %, Sindhi – 37.7 %, Punjabi – 32.6 %, Balochi – 32.4 %, Brahui – 30.2 %, Lodhi – 29.3 %, Bengali – 24.6 %, Vishwabhramin – 20.4 %, Makrani – 19.2 %, Mala – 18.4 %, Kusunda – 8.9 %, Kharia – 6.5 %."

References

- Allentoft 2015.

- Anthony 2007, p. 307.

- Morgunova & Khokhlova 2013.

- "Europe's fourth ancestral 'tribe' uncovered". BBC. 16 November 2015.

- Jeong et al. 2019.

- Novembre 2015, "evidence to support theories of a back-migration from Corded Ware-related populations that contributed to the origins of the Sintashta culture in the Urals and their descendants, the Andronovo."

- Haak et al. 2015.

- Mathieson, et al. 2015.

- Gibbons, Ann (10 June 2015). "Nomadic herders left a strong genetic mark on Europeans and Asians". Science. AAAS.

- Anthony 2007, p. 300-370.

- Nordgvist & Heyd 2020.

- Mallory 1999.

- Mallory 1999, p. 215.

- Anthony 2007, p. 182.

- Anthony 2007, p. 275.

- Anthony 2007, p. 300.

- Mallory 1999, p. 210-211.

- Anthony 2007, p. 321.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 274–277, 317–320.

- Parpola 2015, p. 49.

- Parpola 2015, p. 45.

- Parpola 2015, p. 47.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 301–302.

- Anthony 2007, p. 303.

- Dolukhanov 1996, p. 94.

- Anthony 2007, p. .

- Zimmer, Carl (10 June 2015). "DNA Deciphers Roots of Modern Europeans". New York Times. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- Fortson 2004, p. 43.

- Mallory 1997.

- New research shows how Indo-European languages spread across Asia. Science Daily.

- Jones et al. 2015.

- Anthony 2019b, p. 36.

- Anthony 2019a, p. 1-19.

- Dolukhanov, Pavel M. (2003). "Archaeology and Languages in Prehistoric Northern Eurasia" (PDF). Japan Review. 15: 175–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-09.

- Lazaridis et al. 2016, p. 8.

- Gallego-Llorente et al. 2016.

- Pashnick 2014, p. 33.

- Mathieson, et al. 2018.

- Wang 2019.

- Kuzmina 2007, pp. 383-385.

- Wilde et al. 2014.

- Anthony 2017.

- Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- Haak et al. 2015, pp. 121–124.

- Haak et al. 2015, p. 5.

- Cassidy et al. 2016.

- Martiniano, et al. 2017.

- Lazaridis et al. 2014.

- Jones et al. 2017.

- Haak et al. 2015, pp. 121–122.

- Pathak et al. 2018.

- Lazaridis et al. (2016), pp. 123.

- Lazaridis et al. (2016).

- Unterländer et al. 2017.

Notes

- See also Eurogenes Blog (December 18, 2017), Corded Ware as an offshoot of Hungarian Yamnaya (Anthony 2017)

Sources

- Allentoft, Morten E.; et al. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691058870.

- Anthony, David (2017). "Archaeology and Language: Why Archaeologists Care About the Indo-European Problem". In Crabtree, P.J.; Bogucki, P. (eds.). European Archaeology as Anthropology: Essays in Memory of Bernard Wailes.

- Anthony, David (Spring–Summer 2019a). "Archaeology, Genetics, and Language in the Steppes: A Comment on Bomhard". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 47 (1–2). Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- Anthony, David W. (2019b). "Ancient DNA, Mating Networks, and the Anatolian Split". In Serangeli, Matilde; Olander, Thomas (eds.). Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Stages of Indo-European. BRILL. pp. 21–54. ISBN 978-9004416192.

- Cassidy LM, Martiniano R, Murphy EM, Teasdale MD, Mallory J, Hartwell B, Bradley DG (2016). "Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome". PNAS. 113 (2): 368–373. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..368C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518445113. PMC 4720318. PMID 26712024.

- Dolukhanov, Pavel M. (1996), The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus, New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-23627-4

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing

- Gallego-Llorente M, Connell S, Jones ER, Merrett DC, Jeon Y, Eriksson A, et al. (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Scientific Reports. 6: 31326. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631326G. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

- Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Jeong, Choongwon; Balanovsky, Oleg; Lukianova, Elena; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; et al. (29 April 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia languages in Europe". Nature Ecology and Evolution. Nature Research. 3 (6): 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. hdl:10871/36562. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- Jones, Eppie R.; Gonzalez-Fortes, Gloria; Connell, Sarah; Siska, Veronika; et al. (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. 6: 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- Jones ER, Zarina G, Moiseyev V, Lightfoot E, Nigst PR, Manica A, Pinhasi R, Bradley DG (2017). "The Neolithic transition in the Baltic was not driven by admixture with early European farmers". Current Biology. 27 (4): 576–582. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.060. PMC 5321670. PMID 28162894.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Mittnik, Alissa; Renaud, Gabriel; et al. (2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Lazaridis I, Nadel D, Rollefson G, Merrett DC, Rohland N, Mallick S, et al. (16 June 2016). "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers". bioRxiv 10.1101/059311, Supplementary Information

Lazaridis I, Nadel D, Rollefson G, Merrett DC, Rohland N, Mallick S, et al. (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature (published August 2016). 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054. - Mallory, J. P. (1997), "Yamna Culture", Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn

- Mallory, J.P. (1999), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth (reprint ed.), London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7

- Martiniano, R, et al. (2017). "The population genomics of archaeological transition in west Iberia: Investigation of ancient substructure using imputation and haplotype-based methods". PLOS Genet. 13 (7): e1006852. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006852. PMC 5531429. PMID 28749934.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (10 October 2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/016477.

Mathieson, Iain; et al. (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature (published 24 December 2015). 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274. - Mathieson, Iain; et al. (21 February 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Morgunova, Nina; Khokhlova, Olga (2013). "Chronology and Periodization of the Pit-Grave Culture in the Area Between the Volga and Ural Rivers Based on 14C Dating and Paleopedological Research". Radiocarbon. 55 (2–3): 1286–1296. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16087. ISSN 0033-8222.

- Narasimhan VM, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Rohland N, et al. (2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Nordgvist, Kerkko; Heyd, Volker (2020). "The Forgotten Child of the Wider Corded Ware Family: Russian Fatyanovo Culture in Context". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 86: 65–93. doi:10.1017/ppr.2020.9. hdl:10138/321831. S2CID 228923806.

- Novembre, John (11 June 2015). "Ancient DNA steps into the language debate" (PDF). Nature. 522 (7555): 164–165. doi:10.1038/522164a. PMID 26062506. S2CID 205085294.

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism, Oxford University Press

- Pashnick, Jeff (August 2014). Genetic Analysis of Ancient Human Remains from the Early Bronze Age Cultures of the North PonticSteppe Region. Masters Theses (MS thesis). 737. Grand Valley State University. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- Pathak AK, Kadian A, Kushniarevich A, Montinaro F, Mondal M, Ongaro L, et al. (6 December 2018). "The Genetic Ancestry of Modern Indus Valley Populations from Northwest India". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (6): 918–929. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.022. PMC 6288199. PMID 30526867.

- Unterländer, Martina; Palstra, Friso; Lazaridis, Iosif; Pilipenko, Aleksandr; Hofmanová, Zuzana; Groß, Melanie; et al. (2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao (4 February 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions Eurasia". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 10 (1): 590. bioRxiv 10.1101/322347. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

- Wilde S, Timpson A, Kirsanow K, Kaiser E, Kayser M, Unterländer M, et al. (2014). "Direct evidence for positive selection of skin, hair, and eye pigmentation in Europeans during the last 5,000 y". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (13): 4832–4837. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4832W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316513111. PMC 3977302. PMID 24616518.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yamna culture. |

- "Genetic study revives debate on origin and expansion of Indo-European Languages". Science Daily. March 2015.