Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Belgrade, capital of Yugoslavia, was the host of the First Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in early September 1961. City hosted the Ninth Summit as well in September 1989.

Non-alignment and active participation in the movement was the corner-stone of the Cold War period foreign policy and ideology of the Yugoslav federation.[1] As the only European socialist state beyond the Eastern Bloc and a country economically linked to Western Europe Yugoslavia championed balancing and cautious equidistance[2] towards United States, Soviet Union and China in which Non-alignment was perceived as a collective guarantee of country's political independence.[3] In addition Non-alignment opened further maneuver space in status quo Cold War Europe compared to neutral countries whose foreign policy was often limited by great powers, most notably in the case of Finlandization.[4]

The end of the Cold War and subsequent breakup of Yugoslavia, one of the founding and core members, seemed to bring into question the very existence of the Movement which was preserved only by politically pragmatic chairmanship of Indonesia.[5]

History

Origins

During the World War II Yugoslav Partisans liberated their country with only minimal help from the Soviet Red Army and western allies which led the new communist authorities to the belief that contrary to other countries in Eastern Europe they are entitled to follow a more independent socialist course. Contrary to other communist parties in the region, Communist Party of Yugoslavia was able to rely on local army, police and relatively high legitimacy among diverse Yugoslav demographic groups. Yugoslavia did not perceive itself as a client but as a partner of the USSR and in many respect pursued its own domestic and foreign policy which sometimes was more assertive than Moscow's policy. This was the case in over the issue of Free Territory of Trieste, Balkan Federation, Greek Civil War, Austro-Slovene conflict in Carinthia and infiltration and relations with the Albanian National Liberation Movement. Belgrade's independent policies raised tensions with Moscow and escalated in 1948 Tito–Stalin split Yugoslavia when found itself isolated from the rest of the Eastern Bloc countries and in need to redefine its foreign policy.

The country initially oriented itself towards the Western Bloc and signed the 1953 Balkan Pact with NATO member states of Kingdom of Greece and Turkey. After the death of Stalin, Yugoslav relations with the USSR improved with the country's verbal support for the Soviet intervention in Hungary (contrary to the 1968 one in Czechoslovakia). 1955 Belgrade declaration decreased reliance on the 1953 Balkan Pact which subsequently discontinued its activities. As the country still wanted to preserve its newly gained independence it developed relations with European neutral countries such as Finland. It also avoided joining the Warsaw Pact established in May 1955. Yet in order to avoid isolation in deeply divided Europe, Yugoslavia looked for new allies among former colonies and mandate territories.[6] Yugoslavia supported Egypt during the Suez Crisis, a country which became one of the founding members of the Non-aligned movement. Yugoslavia developed its relations with India, another founding member, from the time of their concurrent mandate at the UN Security Council from the end of 1949 onward.[7]

A year later, during the 1950 United Nations General Assembly session prominent Yugoslav politician and at the time Minister of Foreign Affairs Edvard Kardelj stated that "Yugoslavia cannot accept that mankind must choose between domination by one or other power".[2] On 22 December 1954 meeting in New Delhi Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito signed a joint statement stipulating that "the policy of non-alignment adopted and pursued by their respective countries is not ‘neutrality’ or ‘neutralism’ and therefore passivity, as sometimes alleged, but is a positive, active and constructive policy seeking to lead to collective peace".[7]

From 1956 Brijuni Meeting until the 1961 Belgrade Conference

Meeting between Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President of Egypt Gamal Abdel Nasser took place on the Brijuni Islands in the Yugoslav constituent Socialist Republic of Croatia on 19 July 1956.[8] Three leaders signed a document expressing that: "Peace cannot be achieved via division, but via striving for collective security on the global scale. Achieved by the expansion of the area of freedom, as well as through the ending of domination of one country over another."[8]

In late 1958 and early 1959 president Tito and the rest of Yugoslav delegation initiated 3 months long international boat trip on a board of the Yugoslav training ship Galeb.[9] During the trip delegation visited Indonesia, India, Burma, Ceylon, Ethiopia, Sudan, Egypt and Syria.[9] Indonesian president Sukarno called Tito a world citizen while Tito referred to the Bandung Conference by saying "Bandung is the place from which a new spirit originated which permeate humanity".[9] During his stay in Bandung president Tito received honorary doctorate in law.[9]

The 1961 Non-Aligned Conference in Belgrade

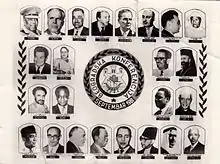

The 1961 Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement was the first official conference of the Non-Aligned Movement.[10] Major contributing factor to the organization of the conference was the process of decolonization of a number of African countries in the 1960s.[10] Some therefore called it the ″Third World’s Yalta″ in reference to 1945 Yalta Conference.[10] 25 countries in total participated in Belgrade Conference including Afghanistan, Algeria, Burma, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Yemen, Yugoslavia, Cambodia, Cyprus, Tunisia, United Arab Republic, Ceylon, while 3 countries, Bolivia, Brazil and Ecuador, were observers.[11] The preparatory meeting of Non-Aligned Countries took place earlier that year in Cairo between 5–12 June 1961.[12] One of the issues was division of the newly independent countries over the Congo Crisis which led to rift and creation of conservative and anti-radical Brazzaville Group and radical nationalist Casablanca Group.[10] All members of the Casablanca Group attended the conference, including Algeria, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Morocco and the United Arab Republic, while none of the Brazzaville Group was present.[10]

President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah and President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito arrive at the Conference

President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah and President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito arrive at the Conference Leaders' group photo

Leaders' group photo The venue of the Conference

The venue of the Conference

The 1989 Non-Aligned Conference in Belgrade

In an effort to rebuild internal cohesion via success in foreign policies post-Tito Yugoslavia tried to participate in a number of multilateral initiatives and to host prominent events. One of them was successful bid to host the 1989 Non-Aligned Conference in Belgrade after the city hosted the first conference in 1961. The initiative was pushed by the new Yugoslav foreign minister from the Socialist Republic of Croatia and future 1993-1996 UN Secretary General's Special Advisor on the NAM Budimir Lončar.[9] It was expected that the new host will come from Latin America but at the time Nicaragua, which was the only Latin American country strongly lobbying to host the event, was not preferred choice among significant number of the member states.[9]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

At the time of Breakup of Yugoslavia in early 1990s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was at the end of its 1989-1992 chairmanship of the movement and was about to transfer its chairmanship to Indonesia. At the time, the rotation of the NAM chairpersons following the 1989 Belgrade Conference was the most dynamic in the history of the movement with 5 chairpersons in total. Yugoslav crisis created logistical and legal issues in the smooth transfer to Indonesian chairmanship. At the time of 1–6 September 1992 conference in Jakarta Yugoslav Wars already started, former Yugoslav republics of Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia-Herzegovina already joined the United Nations as new member states while UN imposed sanctions against Yugoslavia. At the time the new state the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (constisting of Serbia and Montenegro) claimed to be the sole legal successor of the Socialist Yugoslavia which was rejected in the United Nations Security Council Resolution 777 a couple of days following the Jakarta conference. The Yugoslav Crisis created unprecedented situation in which the chairperson of the movement (Dobrica Ćosić who was in London at the time) was absent from the conference to transfer the chairmanship to Indonesia.[9] Yugoslav delegation which was without clear instructions from Belgrade was led by Montenegrin diplomat Branko Lukovac.[9] In the absence of clear instruction Yugoslav delegation agreed that the new post-Yugoslav states can participate in the meeting in the status of observers despite the facts that Belgrade did not recognize them at the time.[9] In the partially chaotic circumstances Yugoslav delegation (de facto Serbian and Montenegrin one) managed to achieve results which the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Egypt Amr Moussa described as good for Yugoslavia and better than what should be expected from the United Nations.[9] The movement decided not to expel Yugoslavia from the movement but to instead leave the empty chair and the Yugoslav nametag which was kept until the beginning of the XXI century when after the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević Federal Republic of Yugoslavia dropped its claim on sole succession of the Socialist Yugoslavia.[9] Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was not to be invited to conferences except if Yugoslav issues were discussed.[9] The last Yugoslav delegation was even faced with logistical issue of how to return home due to sanctions in place.[9] They were able to fly to Budapest from where they needed to take bus to return to Yugoslavia, the country which was never again present at the NAM conference.[9]

Ideology

Movement's Core Members

Yugoslavia was the proponent of the equidistance towards both blocs during the Cold War and implicitly questioned non-alignment of some of the movement's members. Belgrade feared that close Soviet ally Cuba, together with other self-described progressive members such as Vietnam, South Yemen, Ethiopia and Angola are trying to link the movement to Eastern Bloc on the basis of Lenin's thesis of the natural identity of interest between Soviet socialism and colonial people of Africa and Asia independence struggle.[13] In late 1970' it was the time for Latin America to host the Conference for the first time after it was already organized once in Europe, once in Asia and three times in Africa.[13] Peru is said to be the first tentative choice for the meeting but this idea was canceled after the overthrow of the president Velasco Alvarado.[13] Yugoslavia, together with India, proposed large number of amendments in an successful effort to change what they saw as unacceptably one-sided pro-Soviet draft of the final declaration of the Havana Conference.[13] Cuba, Iran and Iraq, all of which were perceived to belong to the more radical wing of the movement, were absent from the 1989 Belgrade Conference which led to adoption of more equidistant final document.[5]

European and Mediterranean Element of the Non-Alignment

25 delegations participated at the First Non-Aligned Summit in Belgrade which included Yugoslavia, Cyprus, Algeria, United Arab Republic, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia from Europe or Mediterranean region. Yugoslav diplomacy showed certain mistrust of exclusive Asian–African and Tricontinental initiatives which Belgrade perceived as the effort by Soviets and self-described progressive nations to undermine and obscure Yugoslav and Mediterranean place within the movement of non-Bloc nations.

Yugoslavia cooperated with other non-aligned and with neutral countries in Europe within the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in trying to preserve results of the Helsinki Accords.[1] In this framework Yugoslavia cooperated with Austria and Finland on mediation between blocs, organized second CSCE summit in 1977 in Belgrade and proposed drafts on national minorities protection which are still valid and integral part of OSCE provisions on minority rights.[6] Yugoslav foreign minister Miloš Minić stated that "Yugoslavia is a European, Mediterranean, non-aligned and developing country".[14] During his international trips to other non-aligned countries president Tito underlined the need for the Mediterranean to become a zone of peace.[15]

Due to its perceived Eurocentrism Yugoslavia was sometimes criticized of excessively cautious support to decolonization liberation movements with Belgrade's provision of significant material and logistic support only in the case of the National Liberation Front of Algeria.[2] With the exception of Algeria Yugoslavia focused its support on activities on the Special Committee on Decolonization where it was one of 17 original members and where its representative Miša Pavićević urged the committee to make a recommendation to the General Assembly that would push United Kingdom to give priority in granting independence to its colonies.[2] The country argued that its own historical experiences of foreign domination by Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empire, challenges in development and complex multi-ethnic federalist structure are akin to experiences of newly independent post-colonial countries.

Cultural and scientific cooperation

Non-Aligned News Agencies Pool, predecessor of the NAM News Network, was established in January 1975 when the Yugoslav Agency Tanjug initiated publication of stories from other countries in English, French and Spanish.[2]

Economic cooperation

List of notable Yugoslav projects in Non-Aligned countries

- Babylon Rotana Baghdad Hotel (Baghdad,

Iraq) (1969–1982)[16]

Iraq) (1969–1982)[16] - Entebbe International Airport (Entebbe,

Uganda) (1975)[16]

Uganda) (1975)[16] - FINDECO House (Lusaka,

Zambia)[16]

Zambia)[16] - International Conference Center at Serena Hotel (Kampala,

Uganda) (1975)[16]

Uganda) (1975)[16] - Lagos International Trade Fair (Lagos,

Nigeria) (1974–1977)[16]

Nigeria) (1974–1977)[16] - Ministry of Works and Communications of Ethiopia employed Branko Petrović as the lead architect for its headquarters. (Addis Ababa,

Ethiopia)[17]

Ethiopia)[17] - Kwame Nkrumah University campus employed Miro Marasović as the lead architect. (Kabwe,

Zambia)[17]

Zambia)[17] - National Museum of Aleppo (Aleppo,

Syria)[17]

Syria)[17] - Partially implement General urbanisation plan of Conakry (Conakry,

Guinea) (1961-1963)[17]

Guinea) (1961-1963)[17] - Military Navy Port and residential area (Al-Khums,

Libya)[17]

Libya)[17]

Post-Cold War Developments

After the end of the Cold War and Yugoslav Wars during the Breakup of Yugoslavia six former federal republics of Yugoslavia and its shared successor states showed various levels of interest in participation in Non-Aligned Movement. Yugoslav membership in the movement, which was claimed by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) but disputed in its exclusivity by UNSCR 777, was suspended in 1992 without official removal from membership.[18] In 2001 at the Coordination Bureau and subsequent Ministerial Meeting that same year Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) was recognized as an observer state of NAM.[18] Out of six former Yugoslav republics four (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia) central Serbo-Croatian speaking ones are all observer states within the NAM. Neither of them is a full member state of NAM with Bosnia and Herzegovina's application being refused in 1995. As of 2020 Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Slovenia are all member states of NATO, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a recognized candidate while Serbia is military neutral state. All of them are either member states or aspiring member states of European Union. Earlier European NAM member states left the group once they joined EU (Cyprus and Malta). In addition to six Yugoslav republics, since 2008 province of Kosovo declared unilateral independence. As of 2020 the vast majority of NAM member states did not recognize Kosovo including some of the largest member states such as India, Indonesia, Cuba, South Africa, etc. yet there is no common stance within the NAM on the Kosovo independence precedent.

.jpg.webp)

Serbia: In 2010, for the first time after the end of Yugoslav Wars, Serbia initiated a scholarship program called "World in Serbia - 100 Scholarships for Students from Non-Aligned Movement Member States".[18] On 5–6 September 2011 the Non-Aligned Movement celebrated its 50th anniversary in Belgrade in the House of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia which hosted the first NAM conference.[19][20] 106 delegations confirmed their participation in the 2011 Belgrade NAM Conference.[19] United Nations Secretary-General's message to Additional Commemorative Meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement was delivered by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.[20] The idea for meeting was proposed by the President of Serbia Boris Tadić during his participation at 15th conference in Sharm el-Sheikh.[21] Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dačić participated in 17th Conference on the Margarita Island in Venezuela.[20] Ivica Dačić had also participated in the 2018 ministerial conference in Azerbaijan, where he stated that the Non-Aligned Movement is of the highest importance for Serbia given the cherished legacy of the former Yugoslavia and its President Tito. Dačić expressed regret that his country was only an observer state but at the same time was hopeful for more significant engagement in the future.[22]

Serbia: In 2010, for the first time after the end of Yugoslav Wars, Serbia initiated a scholarship program called "World in Serbia - 100 Scholarships for Students from Non-Aligned Movement Member States".[18] On 5–6 September 2011 the Non-Aligned Movement celebrated its 50th anniversary in Belgrade in the House of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia which hosted the first NAM conference.[19][20] 106 delegations confirmed their participation in the 2011 Belgrade NAM Conference.[19] United Nations Secretary-General's message to Additional Commemorative Meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement was delivered by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.[20] The idea for meeting was proposed by the President of Serbia Boris Tadić during his participation at 15th conference in Sharm el-Sheikh.[21] Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dačić participated in 17th Conference on the Margarita Island in Venezuela.[20] Ivica Dačić had also participated in the 2018 ministerial conference in Azerbaijan, where he stated that the Non-Aligned Movement is of the highest importance for Serbia given the cherished legacy of the former Yugoslavia and its President Tito. Dačić expressed regret that his country was only an observer state but at the same time was hopeful for more significant engagement in the future.[22] Croatia: Croatian president Stjepan Mesić participated in NAM conferences in Havana in 2006 and Sharm el-Sheikh in 2009.[23] President's Office cooperation with NAM member states was facilitated by Budimir Lončar, diplomat with extensive experience from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Yugoslavia.[23] Croatian election to the Eastern European Spot for non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council in 2008-2009 (in open competition with Czech Republic which was member state both of EU and NATO) was ascribed to president's and Croatian Ministry's successful lobbying within the Non-Aligned Movement.[24]

Croatia: Croatian president Stjepan Mesić participated in NAM conferences in Havana in 2006 and Sharm el-Sheikh in 2009.[23] President's Office cooperation with NAM member states was facilitated by Budimir Lončar, diplomat with extensive experience from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Yugoslavia.[23] Croatian election to the Eastern European Spot for non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council in 2008-2009 (in open competition with Czech Republic which was member state both of EU and NATO) was ascribed to president's and Croatian Ministry's successful lobbying within the Non-Aligned Movement.[24]

See also

- Yugoslavia and the United Nations

- Yugoslavia and the European Economic Community

- India and the Non-Aligned Movement

- Egypt and the Non-Aligned Movement

- Informbiro period

- Titoism

- World War II in Yugoslavia

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Yugoslavia)

- Museum of Yugoslavia

- Museum of African Art, Belgrade

- Archives of Yugoslavia

- Diplomatic Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia

- Park of Friendship, New Belgrade

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- Institute of International Politics and Economics

- Foreign relations of Serbia

- Foreign relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Foreign relations of Croatia

- Foreign relations of Montenegro

- Foreign relations of North Macedonia

- Foreign relations of Slovenia

Further reading

Books

- Alvin Z. Rubinstein (1970). Yugoslavia and the Nonaligned World. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Kardelj, Edvard (1975). Istorijski koreni nesvrstavanja. (in Serbo-Croatian) [English: The Historical Roots of Non-Alignment]. Belgrade: Komunist.

- Jakovina, Tvrtko (2011). Treća strana Hladnog rata. (in Croatian) [English: The Third Side of the Cold War]. Zaprešić: Fraktura.[25]

- Kullaa, Rinna (2012). Non-alignment and Its Origins in Cold War Europe: Yugoslavia, Finland and the Soviet Challenge. London; New York, N.Y.: I.B. Tauris.

- Videkanić, Bojana (2020). Nonaligned Modernism: Socialist Postcolonial Aesthetics in Yugoslavia 1945–1985. Montreal: McGill–Queen's University Press.[26]

Web materials

- Stubbs, Paul. Socialist Yugoslavia and the Antinomies of the Non-Aligned Movement. Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières.

References

- Martinović, S. (1983). "Foreign Policy of Yugoslavia". Pakistan Horizon. 36 (1): 28–31. JSTOR 41394717.

- Iheanacho, Vitalis Akujiobi (1987). Nonalignment: Cuba and Yugoslavia in the Nonaligned Movement 1979-1986 (Master's Thesis). North Texas State University. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "'Yugocentrism': Belgrade's Balancing Actas Friend of East, West and Nations In Between". New York Times: 12. 28 December 1964.

- Kullaa, Rinna (2012). Non-alignment and Its Origins in Cold War Europe: Yugoslavia, Finland and the Soviet Challenge. I.B. Tauris.

- Schiavone, Giuseppe (2008). International Organizations: A dictionary and directory (Seventh ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-230-57322-2.

- Trültzsch, Arno. "An Almost Forgotten Legacy: Non-Aligned Yugoslavia in the United Nations and in the Making of Contemporary International Law".

- Mišković, Nataša (2009). "The Pre-history of the Non-Aligned Movement: India's First Contacts with the Communist Yugoslavia, 1948–50" (PDF). India Quarterly. 65 (2): 185–200. doi:10.1177/097492840906500206. S2CID 154101021.

- Krajcar, Dražem. "Tito, Nehru i Naser na Brijunima dogovorili osnivanje Pokreta nesvrstanih – 1956". Povijest.hr.

- Jakovina, Tvrtko (2011). Treća strana Hladnog rata. Fraktura. ISBN 978-953-266-203-0.

- Ancic, Ivana (17 August 2017). "Belgrade, The 1961 Non-Aligned Conference". Global South Studies. University of Virginia.

- Pantelic, Nada (2011). "The First Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries (in Serbian and English)". Exhibition Catalog. Archives of Yugoslavia. ISBN 978-86-80099-35-4.

- "2011.- "The first conference of the Heads of state or Government of Non-aligned countries, Belgrade 1961"". Archives of Yugoslavia. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Cviic, K. F. (1979). "Note of the Month". The World Today. 35 (10): 387–390. JSTOR 40395078.

- Singleton, F. B. (1980). "Yugoslavia without Tito". The World Today. 36 (6): 204–208. JSTOR 40395190.

- Hasan, Sabiha (1981). "Yugoslavia's Foreign Policy Under Tito (1945-1980) - II". Pakistan Horizon. 34 (4): 62–103. JSTOR 41394138.

- Niebyl, Donald (29 March 2020). "10 Works of Yugoslav Modernist Architecture in Africa & the Middle East". The Spomenik Database. The Spomenik Database. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Pulig, Srećko (16 December 2020). "Kako smo gradili Treći svijet". Novosti (Croatia). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "Republika Srbija u Pokretu Nesvrstanih Zemalja (PNZ)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Serbia). Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Serbia, RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of. "Nesvrstani ponovo u Beogradu". Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "Secretary-General's Message to Additional Commemorative Meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement – United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon". 5 September 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "Tadić: Nesvrstani ponovo u Beogradu 2011". Radio Television of Vojvodina. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Milinković, Danijelal (6 April 2018). "Nesvrstani su uvek uz nas". Večernje novosti. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Nesvrstanima hrvatski zbogom nakon ulaska u EU". Slobodna Dalmacija. 7 March 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Avdović, Erol (17 October 2007). "Hrvatska izabrana u Vijeće sigurnosti UN-a kao nestalna članica". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "The Third Side of the Cold War: Movement of the Non-aligned States, Yugoslavia and the World". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Nonaligned Modernism: Socialist Postcolonial Aesthetics in Yugoslavia 1945–1985". McGill–Queen's University Press. Retrieved 24 October 2020.