24 Hours of Daytona

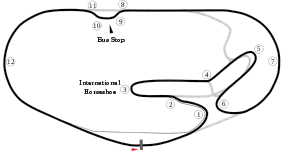

The 24 Hours of Daytona, currently known as the Rolex 24 At Daytona for sponsorship reasons, is a 24-hour sports car endurance race held annually at Daytona International Speedway in Daytona Beach, Florida. It is run on a 3.56-mile (5.73 km) combined road course, utilizing portions of the NASCAR tri-oval and an infield road course. Since its inception, it has been held on the last weekend of January or first weekend of February as part of Speedweeks, and it is the first major automobile race of the year in the United States. It is also the first race of the season for the WeatherTech SportsCar Championship.

| |

| |

| WeatherTech SportsCar Championship | |

|---|---|

| Venue | Daytona International Speedway |

| Corporate sponsor | Rolex |

| First race | 1962 |

| Duration | 24 hours |

| Previous names | Daytona 3 Hour Continental (1962–1963) Daytona 2000 (1964–1965) 24 Hours of Daytona (1966–1971, 1973, 1975–1977) 6 Hours of Daytona (1972) 24 Hour Pepsi Challenge (1978–1983) SunBank 24 at Daytona (1984–1991) Rolex 24 At Daytona (1992–) |

| Most wins (driver) | Hurley Haywood (5) Scott Pruett (5) |

| Most wins (team) | Chip Ganassi Racing (6) |

| Most wins (manufacturer) | Porsche (18) |

The race has had several names over the years. Since 1992, the Rolex Watch Company is the title sponsor of the race under a naming rights arrangement, replacing Sunbank (now SunTrust) which in turn replaced Pepsi in 1984. Winning drivers of all classes receive a steel Rolex Daytona watch.

In 2006, the race moved one week earlier into January to prevent a clash with the Super Bowl, which had in turn moved one week later into February a few years earlier.

The race has been known historically as a leg of the informal Triple Crown of endurance racing,[1] although it suffers from an increasing isolation from international Sports Car racing regulations, which have been eased in recent years (Prototypes include P2 Prototypes and an IMSA-spec open engine class with aero kits, and the two Grand Touring classes are now divided between ACO GTE, and FIA/SRO Group GT3 classes).

Beginnings

Shortly after the track opened, on April 5, 1959, a six-hour/1000 kilometer USAC-FIA sports car race was held on the road course. Count Antonio Von Dory and Roberto Mieres won the race in a Porsche, shortened to 560.07 miles due to darkness.[2] The race utilized a 3.81-mile layout, running counter-clockwise.[3]

In 1962, a few years after the track was built, a 3-hour sports car race was introduced. Known as the Daytona Continental, it counted towards the FIA's new International Championship for GT Manufacturers. The first Continental was won by Dan Gurney, driving a 2.7L Coventry Climax-powered Lotus 19.[1] Gurney was a factory Porsche driver at the time, but the 1600-cc Porsche 718 was considered too small and slow for what amounted to a sprint race on a very fast course.

In 1964, the event was expanded to 2,000 km (1,240 mi), doubling the classic 1000 km distance of races at Nürburgring, Spa and Monza. The distance amounted to roughly half of the distance the 24 Hours of Le Mans winners covered at the time, and was similar in length to the 12 Hours of Sebring, which was also held in Florida in March. Starting in 1966, the Daytona race was extended to the same 24-hour length as Le Mans.

24-hour history

Unlike the Le Mans event, the Daytona race is conducted entirely over a closed course within the speedway arena without the use of any public streets. Most parts of the steep banking are included, interrupted with a chicane on the back straight and a sweeping, fast infield section which includes two hairpins. Unlike Le Mans, the race is held in wintertime, when nights are at their longest. There are lights installed around the circuit for night racing, although the infield section is still not as well-lit as the main oval. However, the stadium lights are turned on only to a level of 20%, similar to the stadium lighting setup at Le Mans, with brighter lights around the pit straight, and decent lighting similar to street lights around the circuit.[4]

In the past, a car had to cross the finish line after 24 hours to be classified, which led to dramatic scenes where damaged cars waited in the pits or on the edge of the track close to the finish line for hours, then restarted their engines and crawled across the finish line one last time in order to finish after the 24 hours and be listed with a finishing distance, rather than dismissed with DNF (Did Not Finish). This was the case in the initial 1962 Daytona Continental (then 3 hours), in which Dan Gurney's Lotus 19 had established a lengthy lead when the engine failed with just minutes remaining. Gurney stopped the car at the top of the banking, just short of the finish line. When the three hours had elapsed, Gurney simply cranked the steering wheel to the left (toward the bottom of the banking) and let gravity pull the car across the line, to not only salvage a finishing position, but actually win the race.[1] This led to the international rule requiring a car to cross the line under its own power in order to be classified.

The first 24 Hour event in 1966 was won by Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby driving a Ford Mk. II. Motor Sport reported: "For their first 24-hour race the basic organization was good, but the various officials in many cases were out of touch, childish and lacked the professional touch which one now finds at Watkins Glen."[5] After having lost in 1966 at Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans to the Fords, the Ferrari P series prototypes staged a 1–2–3 side-by-side parade finish at the banked finish line in 1967.[6] The Ferrari 365 GTB/4 road car was given the unofficial name Ferrari Daytona in celebration of this victory.[7]

1966 also saw Suzy Dietrich enter the 24 Hours event, driving a Sunbeam Alpine with Janet Guthrie and Donna Mae Mims. The trio finished 32nd and, along with another women's team in the race, became the first women's teams to finish an international-standard 24-hour race.[8]

Porsche repeated this show in their 1–2–3 win in the 1968 24 Hours. After the car of Gerhard Mitter had a big crash caused by tire failure in the banking, his teammate Rolf Stommelen supported the car of Vic Elford and Jochen Neerpasch. When the car of the longtime leaders Jo Siffert and Hans Herrmann dropped to second due to a technical problem, these two also joined the new leaders while continuing with their car. So Porsche managed to put 5 of 8 drivers on the center of the podium, plus Jo Schlesser and Joe Buzzetta finishing in third place, with only Mitter being left out.[9]

Lola finished 1–2 in the 1969 24 Hours of Daytona. The winning car was the Penske Lola T70-Chevrolet of Mark Donohue and Chuck Parsons.[10] Few spectators witnessed the achievement as Motor Sport reported: "The Daytona 24-Hour race draws a very small crowd, as can be seen from the empty stands in the background."[11]

1970 saw the race with drivers strapped into their cars, and at the start, drove away. Since 1971, races begin with rolling starts.

In 1972, due to the energy crisis, the race was shortened to 6 hours, while for 1974 the race was cancelled altogether.[12] The Sports Car Club of America sanctioning was replaced by the International Motor Sports Association in 1975.[13]

In 1982, following near-continuous inclusion on the World Sportscar Championship, the race was dropped as the series attempted to cut costs by both keeping teams in Europe and running shorter races. The race continued on as part of the IMSA GT Championship.

The regular teams were expanded to three drivers in the 1970s. Nowadays, four drivers compete typically because of the longer night driving. In the ACO LMP2 and SRO Group GT3-based classes, many of these additional drivers are known as "amateur drivers," under current FIA specifications. Amateur drivers are sportsman drivers that have built a career in a non-motorsport related occupation. These type of drivers are typically eligible for IMSA's Jim Trueman and Bob Akin awards, awarded to the top driver who is not a professional at the end of season. These amateur drivers or overage professional drivers (FIA Silver or Bronze are typically for amateur drivers but professional drivers over 55 are automatically classified at this level) are required in the car for a specific number of hours. In the professional-based DPi Prototype and ACO GTE classes, all four drivers are usually professionals. Most often, the fourth driver in all classes is a Daytona-only professional driver of renown that most often has won a major professional championship, such as Scott Dixon, Jeff Gordon, Fernando Alonso, Shane van Gisbergen and Kyle Busch.

Grand American and Daytona Prototypes

After several ownership changes at IMSA which changed the direction the organization followed, it was decided by the 1990s that the Daytona event would align with the Grand-Am series, a competitor of the American Le Mans Series, which, as its name implies, uses the same regulations as the Le Mans Series and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The Grand Am series, though, is instead closely linked to NASCAR and the original ideas of IMSA and focused on controlled costs and close competition.

In order to make sports car racing less expensive than elsewhere, new rules were introduced in 2002. The dedicated Daytona Prototypes (DP) use less expensive materials and technologies and the car's simple aerodynamics reduce the development and testing costs. The DPs began racing in 2003 with six cars in the race.[14]

Specialist chassis makers like Riley, Dallara, and Lola provide the DP cars for the teams and the engines are branded under the names of major car companies like Pontiac, Lexus, Ford, BMW, and Porsche.

Daytona GTs

The Gran Turismo class cars at Daytona are closer to the road versions, similar to the GT3 class elsewhere. For example, the more standard Cup version of the Porsche 996 is used, instead of the usual RS/RSR racing versions. Recent Daytona entries also include BMW M3s and M6s, Porsche 911s, Chevy Camaros and Corvettes, Mazda RX-8s, Pontiac GTO.Rs, and Ferrari F430 Challenges. The Audi R8 and the Ferrari 458 Italia debuted in the 50th anniversary of the race in 2012.

From the era of the IMSA GTO and GTU until the 2015 rule changes, spaceframe cars clad in lookalike body panels to compete in GT (the new BMW M6, Chevrolet Camaro, and Mazda RX-8). These rules are similar to the old GTO specification, but with more restrictions. The intent of spaceframe cars is to allow teams to save money, especially after crashes, where teams can rebuild the cars for the next race at a much lower cost, or even redevelop cars, instead of having to write off an entire car after a crash or at the end of a year.

Starting in 2014 the GT Daytona class was restricted exclusively to Group GT3 cars. Group GT3 is not used at Le Mans.

GX Class

The 2013 race was the first and only year for the GX class. Six cars started in the event. The class consisted of purpose built production Porsche Cayman S and Mazda 6 racecars. Mazda debuted their first diesel racecar there which is the first time a diesel fuel racecar ever started at the Daytona 24. Throughout the race the Caymans were dominant, while all three Mazdas suffered premature engine failure and retired from the race. By a 9 lap lead, the #16 Napleton Porsche Cayman, driven by David Donohue, was the GX winner.

Statistics

Manufacturers

Porsche has the most overall victories of any manufacturer with 22, scored by various models, including the road based 911, 935 and 996. Porsche also won a record 11 consecutive races from 1977 to 1987 and won 18 out of 23 races from 1968 to 1991.

| Rank | Constructor | Wins | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 1968, 1970–71, 1973, 1975, 1977–83, 1985–87, 1989, 1991, 2003 | |

| 2 | 10 | 2005–13, 2015 | |

| 3 | 5 | 1963–64, 1967, 1972, 1998 | |

| 5 | 4 | 2017–20 | |

| 6 | 3 | 1996–97, 1999 | |

| 7 | 2 | 1965–66 | |

| 1988, 1990 | |||

| 1992, 1994 | |||

| 9 | 1 | 1962 | |

| 1969 | |||

| 1976 | |||

| 1984 | |||

| 1993 | |||

| 1995 | |||

| 2000 | |||

| 2001 | |||

| 2002 | |||

| 2004 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2016 | |||

| 2021 |

Engine manufacturers

In addition to their 18 wins as both car and engine manufacturers, Porsche has four wins solely as an engine manufacturer, in 1984, 1995, and two in the Daytona Prototype era in 2009 and 2010.

| Rank | Engine manufacturer | Wins | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 1968, 1970–71, 1973, 1975, 1977–87, 1989, 1991, 1995, 2003, 2009–10 | |

| 2 | 6 | 1965–66, 1997, 1999, 2012, 2015 | |

| 3 | 5 | 1963–64, 1967, 1972, 1998 | |

| 4 | 4 | 2017–20 | |

| 5 | 3 | 1976, 2011, 2013 | |

| 1969, 2001, 2014 | |||

| 2006–08 | |||

| 8 | 2 | 1988, 1990 | |

| 1992, 1994 | |||

| 2004–05 | |||

| 11 | 1 | 1962 | |

| 1993 | |||

| 1996 | |||

| 2000 | |||

| 2002 | |||

| 2016 | |||

| 2021 |

Drivers with the most overall wins

| Rank | Driver | Wins | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 1973, 1975, 1977, 1979, 1991 | |

| 1994, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2013 | |||

| 3 | 4 | 1963, 1964, 1970, 1971 | |

| 1983, 1985, 1989, 1991 | |||

| 1973, 1975, 1976, 1978 | |||

| 1968, 1978, 1980, 1982 | |||

| 7 | 3 | 1970, 1976, 1981 | |

| 1990, 1997, 1999 | |||

| 1994, 1997, 1999 | |||

| 1986, 1987, 1989 | |||

| 2007, 2008, 2013 | |||

| 2008, 2011, 2013 | |||

| 2004, 2014, 2018 | |||

| 2010, 2014, 2018 | |||

| 2006, 2015, 2020 | |||

| 16 | 2 | 1965, 1966 | |

| 1965, 1966 | |||

| 1983, 1985 | |||

| 1986, 1987 | |||

| 1986, 1987 | |||

| 1988, 1990 | |||

| 1982, 1997 | |||

| 1997, 1999 | |||

| 1998, 2002 | |||

| 1998, 2002 | |||

| 1996, 2005 | |||

| 2004, 2010 | |||

| 1996, 2016 | |||

| 2005, 2017 | |||

| 2017, 2019 | |||

| 2019, 2020 | |||

| 2019, 2020 | |||

| 2017, 2021 | |||

| 2018, 2021 |

Overall winners

3-hour duration

| Year | Date | Drivers | Team | Car | Tire | Car # | Distance | Championship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | February 11 | Lotus 19B-Coventry Climax | G | 96 | 312.420 mi (502.791 km) | International Championship for GT Manufacturers | ||

| 1963 | February 17 | Ferrari 250 GTO | G | 18 | 307.300 mi (494.551 km) | International Championship for GT Manufacturers |

2000 km distance

| Year | Date | Drivers | Team | Car | Tire | Car # | Championship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | February 16 | Ferrari 250 GTO | G | 30 | International Championship for GT Manufacturers | ||

| 1965 | February 28 | Ford GT [15] | G | 73 | International Championship for GT Manufacturers |

24-hour duration (1966–1971)

6-hour duration

| Year | Date | Drivers | Team | Car | Tire | Car # | Distance | Championship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | February 6 | Ferrari 312 PB | F | 2 | 739.140 mi (1,189.531 km) | World Championship for Makes |

24-hour duration (1973 and since 1975)

Notes:

References

- Posey, Sam (February 2012). "24 Hours of Daytona: A short history of a long race". Road & Track. 63 (6): 73–77. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Porsche Wins Daytona Race". St. Petersburg Times. 1959-04-06. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- Cadou Jr., Jep (April 3, 1959). "Jep Cadou Jr Calls 'Em". The Indianapolis Star. p. 20. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved July 19, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Race Profile – 24 Hours of Daytona". Sports Car Digest. January 23, 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- Motor Sport, March 1966, Pages 196–197. See also cover photograph and centre spread.

- Motor Sport, March 1967, Pages 180–181. See also cover photograph and centre spread.

- "Focus on 365 GTB4". Official Ferrari website. Ferrari. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- Kelley, Arthur (February 13, 1966). "Porsches and Women Surprise at Daytona". The Boston Globe. Boston. p. 59 – via Newspapers.com.

- Motor Sport, March 1968, Pages 171–172. See also cover photograph and center spread.

- Motor Sport, March 1969, Pages 236, 244.

- Motor Sport, March 1969, Page 201. See also cover photograph.

- "This Day in Autoweek History". Autoweek: 8. February 16, 2015.

- 1975 – The First 24 Hours of Daytona Sanctioned by IMSA - International Motor Racing Research Center

- "Daytona 24 Through The Years". Autoweek. 62 (4): 59–60. February 20, 2012.

- Entries for the fourth annual Daytona Continental, 1965 Daytona Speedweeks Program No 2, 15-28 February 1965, www.racingsportscars.com Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 8 June 2015

- "Official Race Results" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association. 2018-02-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Daytona – List of Races". Racing Sports Cars. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 24 Hours of Daytona. |