Aerosteon

Aerosteon is a genus of megaraptoran dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of Argentina. Its remains were discovered in 1996 in the Plottier Formation, dating to the Santonian stage (about 84 million years ago).[1] They were originally described as coming from the Anacleto Formation.[2] The type and only known species is A. riocoloradense. Its specific name indicates that its remains were found 1 km (0.6 miles) north of the Río Colorado, in Mendoza Province, Argentina.

| Aerosteon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal diagram illustrating air-filled bones | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Megaraptora |

| Family: | †Megaraptoridae |

| Genus: | †Aerosteon Sereno et al. 2009 |

| Type species | |

| †Aerosteon riocoloradense Sereno et al. 2009 | |

They show evidence of a bird-like respiratory system.[2] Aerosteon's name can be translated as air bone and derives from Greek ἀήρ (aer, "air") and ὀστέον (osteon, "bone"). Though the species name was originally published as "riocoloradensis", Greek ὀστέον is neuter gender, so according to the ICZN the species name must be riocoloradense to match.

Discovery

Aerosteon was first described by Sereno et al. in a paper which appeared in the online journal PLoS ONE in September 2008. However, at the time, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature did not recognize online publication of names for new species as valid unless print copies were also produced and distributed to several libraries, and that this action is noted in the paper itself. PLoS ONE initially failed to meet this requirement for Aerosteon. On May 21, 2009, the journal's managing editor coordinated with the ICZN to correct this oversight, publishing a comment to the original paper with an addendum stating that the requirements had been met as of that date. Consequently, though the description appeared in 2008, Aerosteon was not a valid name until 2009.[3]

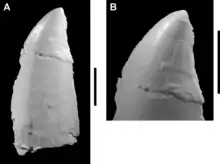

The holotype specimen, MCNA-PV-3137 consists of some cranial bones, a number of partial or complete vertebrae from the neck, back, and sacrum, several cervical and dorsal ribs, gastralia, furcula (wishbone), left scapulocoracoid, left ilium, and left and right pubes. The incomplete fusion of some of its bones indicate that it was not quite fully mature. No dental material is known for this taxon as the isolated tooth initially referred to the holotype[2] was revealed to belong to an abelisaurid theropod.[4]

Description

Aerosteon was approximately 6 meters (20 ft) long and 500 kg (1,100 lbs) according to Gregory S. Paul, whereas Molina-Pérez and Larramendi estimated its length at 7.5 meters (25 ft), its weight at 1 metric ton (2,200 lbs).[5][6]

Classification

Aerosteon did not initially appear to belong to any of the three groups of large theropods that were known to have inhabited the southern continents during this time (namely the Abelisauridae, Carcharodontosauridae or Spinosauridae). Sereno suggested that it might be related to the allosauroid radiation of the Jurassic period, and this was supported in subsequent studies that recognized a clade of late-surviving, lightly built, advanced allosauroids with large hand claws similar to the spinosaurs, called the Megaraptora, within the allosaur family Neovenatoridae.[7] A later analysis has placed Megaraptora, including Aerosteon, within the Tyrannosauroidea.[8] Megaraptorans have since been also considered as non-tyrannosauroid basal coelurosaurs in some analyses.[9][10]

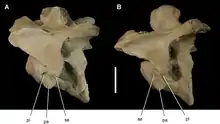

A very close relative of Aerosteon, Murusraptor, was described in 2016 which preserved some bones with a lesser level of pneumaticity. However, the Murusraptor holotype also preserved several teeth which were very dissimilar to the one tooth observed in Aerosteon's holotype. The authors of the description noted that this tooth closely resembled that of abelisaurids and was probably incorrectly referred to Aerosteon. Murusraptor and Aerosteon are practically identical in the structure of their cranial bones and vertebrae, only noticeably differing in the proportions of the ilium, with Aerosteon's ilium being taller than that of Murusraptor.[11]

The cladogram below follows the 2010 analysis by Benson, Carrano and Brusatte, which considered megaraptorans as tetanurans.[7]

| Neovenatoridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cladogram shown below follows an analysis by Porfiri et al., 2014, which recovered megaraptorans as tyrannosauroids.[13]

| Megaraptora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

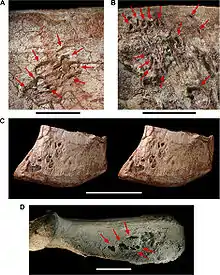

Some of Aerosteon's bones show pneumatization (air-filled spaces), including pneumatic hollowing of the furcula and ilium, and pneumatization of several gastralia, suggesting that it may have had a respiratory air-sac system similar to that of modern birds. These air sacs would have acted like bellows, moving air into and out of the animal's relatively inflexible lungs, instead of the lungs themselves being expanded and contracted as occurs with mammals. See avian respiratory system for more detailed information on this.

Sereno et al. theorize that this respiratory system may have developed to assist with regulating body temperature and was later co-opted for breathing.[2]

References

- Novas, F.E.; Agnolin, F.L.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Porfiri, J.; Canale, J.I. (October 1, 2013). "Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 45: 174–215. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.04.001. ISSN 0195-6671. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Sereno, P.C.; Martinez, R.N.; Wilson, J.A.; Varricchio, D.J.; Alcober, O.A.; Larsson, H.C.E. (2008). Kemp, Tom (ed.). "Evidence for Avian Intrathoracic Air Sacs in a New Predatory Dinosaur from Argentina". PLoS ONE. 3 (9): e3303. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3303S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003303. PMC 2553519. PMID 18825273.

- PLoS ONE Group (2009). "Steps taken to meet the requirements of the ICZN to make new taxonomic names nomenclaturally available." Comment on Original Article: "Evidence for Avian Intrathoracic Air Sacs in a New Predatory Dinosaur from Argentina." PLoS ONE, May 21, 2009.

- Hendrickx, Christophe; Tschopp, Emanuel; Ezcurra, Martín D. (April 1, 2020). "Taxonomic identification of isolated theropod teeth: The case of the shed tooth crown associated with Aerosteon (Theropoda: Megaraptora) and the dentition of Abelisauridae". Cretaceous Research. 108: 104312. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104312. ISSN 0195-6671.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 99.

- Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Spain: Larousse. p. 264.

- Benson R.B.J.; Carrano M.T.; Brusatte S.L. (2010). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...71B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771.

- F. E. Novas; F. L. Agnolín; M. D. Ezcurra; J. I. Canale; J. D. Porfiri (2012). "Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana". Ameghiniana. 49 (Suppl): R33. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- Apesteguía, S; Smith, N.D.; Valieri, R.J.; Makovicky, P.J. (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLoS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.

- Novas, F.E.; Aranciaga Rolando, A.M.; Agnolín, F.L. (2016). "Phylogenetic relationships of the Cretaceous Gondwanan theropods Megaraptor and Australovenator: the evidence afforded by their manual anatomy" (PDF). Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 74: 49–61. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.2016.74.05. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2016.

- Coria, Rodolfo A.; Currie, Philip J. (July 20, 2016). "A New Megaraptoran Dinosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Megaraptoridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157973. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157973C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157973. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4954680. PMID 27439002.

- Zanno, L. E.; Makovicky, P. J. (2013). "Neovenatorid theropods are apex predators in the Late Cretaceous of North America". Nature Communications. 4: 2827. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2827Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms3827. PMID 24264527.

- Juan D. Porfiri; Fernando E. Novas; Jorge O. Calvo; Federico L. Agnolín; Martín D. Ezcurra; Ignacio A. Cerda (2014). "Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation". Cretaceous Research. 51: 35–55. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.04.007.