Appalachiosaurus

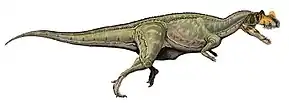

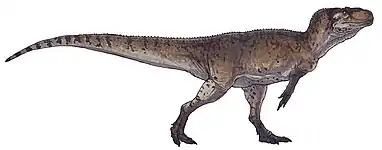

Appalachiosaurus (/ˌæpəˌleɪtʃioʊˈsɔːrəs/ ap-ə-LAY-chee-o-SAWR-əs; "Appalachian lizard") is a genus of tyrannosauroid theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of eastern North America. Like almost all theropods, it was a bipedal predator. Only a juvenile skeleton has been found, representing an animal over 7 meters (23 ft) long and weighing over 600 kilograms (1300 lb), which indicates an adult would have been even larger. It is the most completely known theropod from the eastern part of North America.

| Appalachiosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Eutyrannosauria |

| Genus: | †Appalachiosaurus Carr et al., 2005 |

| Species: | †A. montgomeriensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Appalachiosaurus montgomeriensis Carr et al., 2005 | |

Fossils of Appalachiosaurus were found in central Alabama, from the Demopolis Chalk Formation. This formation dates to the middle of the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, or around 77 million years ago.[1] Fossil material assigned to A. montegomeriensis is also known from the Donoho Creek and Tar Heel-Coachman formations of North and South Carolina.[2]

Discovery and naming

The type specimen was found by Auburn University geologist David King in eastern North America in July 1982.[3] This dinosaur was named after the region of the eastern United States known as Appalachia, which also gave its name to the ancient island continent on which Appalachiosaurus lived. Both are named after the Appalachian Mountains. The generic name also includes the Greek word sauros ("lizard"), the most common suffix used in dinosaur names. There is one known species, A. montgomeriensis, which is named after Montgomery County in the U.S. state of Alabama. Both genus and species were named in 2005 by paleontologists Thomas Carr, Thomas Williamson, and David Schwimmer.

Description

Appalachiosaurus is so far known from only partial remains, including parts of the skull and mandible (lower jaw), as well as several vertebrae, parts of the pelvis, and most of both hindlimbs. These remains are housed at the McWane Science Center in Birmingham, Alabama. There are several open sutures between bones of the skull, indicating that the animal was not an adult. Several elements are crushed, but the specimen is still informative and shows many unique characteristics, or apomorphies. Several of these apomorphies have been identified in the skull, and the claws of the feet show an unusual protrusion on the end closest to the body. A row of six low crests lines the top of the snout, similar to the Asian Alioramus, although most tyrannosaur species exhibit ornamentation to varying degrees on top of the snout. The only remains found are from a juvenile, meaning that the size and weight of the adult is not known. Appalachiosaurus is significantly different and more derived than another early tyrannosaur from eastern North America, Dryptosaurus.

The forelimbs of Appalachiosaurus are poorly known. Large tyrannosaurids are characterized by proportionally small forelimbs and hands with two functional digits each; except some reports of a humerus ascribed to Appalachiosaurus, no forelimb material are known.[4] Early reconstructions gave it long arms with three fingers, but they are now thought to have been much shorter, with only two fingers. Museum mounts have been corrected accordingly.[5] Appalachiosaurus had a bite force of around 32,500 newtons, or 7,193 pounds per square inch. [6]

Classification

The only known specimen Appalachiosaurus was complete enough to be included in phylogenetic analyses using cladistics. The first was performed before the animal had even been named, and found Appalachiosaurus to be a member of the albertosaurine subfamily of Tyrannosauridae, which also includes Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus.[7] The original description also included a cladistic analysis, finding A. montgomeriensis to be a basal tyrannosauroid outside of Tyrannosauridae.[1] However, Asian tyrannosaurs like Alioramus, and Alectrosaurus were excluded, as was Eotyrannus from England. Earlier tyrannosaurs such as Dilong and Guanlong had not been described at the time this analysis was performed. These exclusions may have a significant effect on the phylogeny.

Below is a cladogram published in 2013 by Loewen et al..[8]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Possible pathology

Two vertebrae of the tail were found to be fused together, possibly a result of new bone growth following some sort of injury.[1]

See also

References

- Carr, T.D.; Williamson, T.E.; Schwimmer, D.R. (2005). "A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 119–143. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0119:ANGASO]2.0.CO;2.

- Brownstein, Chase D. (2018-02-08). "The biogeography and ecology of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaurs of Appalachia". Palaeontologia Electronica. 21 (1): 1–56. doi:10.26879/801. ISSN 1094-8074.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2014-01-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jovanelly, T.J.; Lane, L. (2012). "Comparison of the Functional Morphology of Appalachiosaurus and Albertosaurus" (PDF). The Open Geology Journal. 6: 65–71. doi:10.2174/1874262901206010065. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-31.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2013-04-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jovanelly, Tamie J.; Lane, Lesley (September 2012). "Comparison of the Functional Morphology of Appalachiosaurus and Albertosaurus". The Open Geology Journal. 6 (1): 65–71. doi:10.2174/1874262901206010065.

- Holtz, T.R. (2004). "Tyrannosauroidea." In: Weishampel, D.A., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 111–136.

- Loewen, M.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, David C (ed.). "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79420. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420. PMC 3819173. PMID 24223179.