Megaraptor

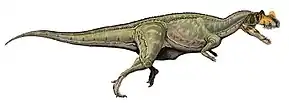

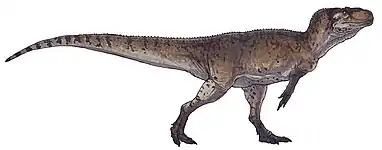

Megaraptor ("giant thief") is a genus of large theropod dinosaur that lived in the Turonian to Coniacian ages of the Late Cretaceous.[2][3] Its fossils have been discovered in the Patagonian Portezuelo Formation of Argentina. Initially thought to have been a giant dromaeosaur-like coelurosaur, it was classified as a neovenatorid allosauroid in previous phylogenies, but more recent phylogeny and discoveries of related megaraptoran genera has placed it as either a basal tyrannosauroid or a basal coelurosaur.[4]

| Megaraptor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed hand | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Megaraptora |

| Family: | †Megaraptoridae |

| Genus: | †Megaraptor Novas 1998 |

| Species: | †M. namunhuaiquii |

| Binomial name | |

| †Megaraptor namunhuaiquii Novas 1998 | |

Description

Megaraptor was initially described as a giant dromaeosaur, known primarily from a single claw (about 30 cm long) that resembled the sickle-shaped foot claw of dromaeosaurids.[2] The discovery of a complete front limb, however, showed that this giant claw actually came from the first finger of the hand. In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated its length at 8 metres (26 ft), its weight at 1 tonne (2,200 lb).[5] The hands were unusually elongated, bearing sickle-shaped claws even more recurved than those of spinosaurids.[6]

Classification

The hand is quite distinct from other basal tetanurans, so it was not initially clear whether Megaraptor was an allosaurid, a carcharodontosaurid, a spinosauroid, or something else entirely.[3] Subsequent studies, as well as the identification of close relatives with similar large claws on the forelimbs (see below), helped identify Megaraptor as a highly advanced and lightly built allosauroid, and a member of the family Neovenatoridae.[7] More recent studies have proposed that Megaraptor and its kin are actually tyrannosauroids[8] or spinosauroids[9] as opposed to allosauroids.[8] A juvenile specimen described in 2014 has provided more evidence towards Megaraptor being a primitive tyrannosauroid.[10] The discovery of Gualicho indicates that Megaraptor may not be a tyrannosauroid, but either an allosauroid or basal coelurosaur.[11]

When first discovered and prior to publication, the spinosaurid Baryonyx was also reported to be a dromaeosaurid, and the allosauroid Chilantaisaurus was reported to be a possible spinosaurid, both based on the large hand claws.

The cladogram shown below follows an analysis by Porfiri et al., 2014.[12]

| Megaraptora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Novas, F.E. (1998). "Megaraptor namunhuaiquii, gen. et sp. nov., a large-clawed, Late Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18: 4–9. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011030.

- Calvo, J. O.; Porfiri, J.D.; Veralli, C.; Novas, F.E.; Poblete, F. (2004). "Phylogenetic status of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii Novas based on a new specimen from Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 41: 565–575.

- "Just out | A new megaraptoran theropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Bajo de la Carpa Formation of northwestern Patagonia @ Cretaceous Research".

- Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 99

- Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D., González-Riga, B.J., and Kellner, A.W. (2007) "A new Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem from Gondwana with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 79(3): 529-41.

- Benson, R.B.J.; Carrano, M.T; Brusatte, S.L. (2010). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...71B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771.

- F. E. Novas; F. L. Agnolín; M. D. Ezcurra; J. I. Canale; J. D. Porfiri (2012). "Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana". Ameghiniana. 49 (Suppl): R33.

- Holtz, T.R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House Books for Young Readers. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- Porfiri, J. D., Novas, F. E., Calvo, J. O., Agnolín, F. L., Ezcurra, M. D. & Cerda, I. A.; Novas; Calvo; Agnolín; Ezcurra; Cerda (2014). "Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation". Cretaceous Research. 51: 35–55. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.04.007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Apesteguía, Sebastián; Smith, Nathan D.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén; Makovicky, Peter J. (2016). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.

- Juan D. Porfiri; Fernando E. Novas; Jorge O. Calvo; Federico L. Agnolín; Martín D. Ezcurra; Ignacio A. Cerda (2014). "Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation". Cretaceous Research. 51: 35–55. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.04.007.