Ceratosaurus

Ceratosaurus /ˌsɛrətoʊˈsɔːrəs/ (from Greek κέρας/κέρατος, keras/keratos meaning "horn" and σαῦρος sauros meaning "lizard") was a carnivorous theropod dinosaur in the Late Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian). This genus was first described in 1884 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh based on a nearly complete skeleton discovered in Garden Park, Colorado, in rocks belonging to the Morrison Formation. The type species is Ceratosaurus nasicornis.

| Ceratosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

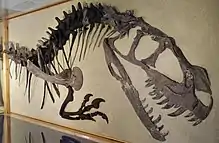

| Cast of a Ceratosaurus from the Cleveland Lloyd Quarry, on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Ceratosauridae |

| Genus: | †Ceratosaurus Marsh, 1884 |

| Type species | |

| †Ceratosaurus nasicornis Marsh, 1884 | |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Garden Park specimen remains the most complete skeleton known from the genus, and only a handful of additional specimens have been described since. Two additional species, Ceratosaurus dentisulcatus and Ceratosaurus magnicornis, have been described in 2000 from two fragmentary skeletons from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry of Utah and from the vicinity of Fruita, Colorado. The validity of these additional species has been questioned, however, and all three skeletons possibly represent different growth stages of the same species. In 1999, the discovery of the first juvenile specimen was reported. Since 2000, a partial specimen was excavated and described from the Lourinhã Formation of Portugal, providing evidence for the presence of the genus outside of North America. Fragmentary remains have also been reported from Tanzania, Uruguay, and Switzerland, although their assignment to Ceratosaurus is currently not accepted by most paleontologists.

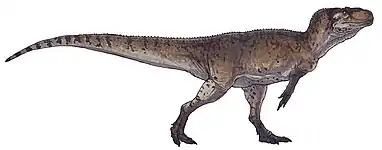

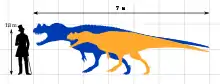

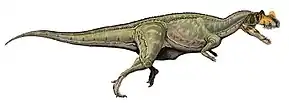

Ceratosaurus was a medium-sized theropod. The original specimen is estimated to be 5.3 m (17 ft) or 5.69 m (18.7 ft) long, while the specimen described as C. dentisulcatus was larger, at around 7 m (23 ft) long. Ceratosaurus was characterized by deep jaws that supported proportionally very long, blade-like teeth, a prominent, ridge-like horn on the midline of the snout, and a pair of horns over the eyes. The forelimbs were very short, but remained fully functional; the hand had four fingers. The tail was deep from top to bottom. A row of small osteoderms (skin bones) was present down the middle of the neck, back, and tail. Additional osteoderms were present at unknown positions on the animal's body.

Ceratosaurus gives its name to the Ceratosauria, a clade of theropod dinosaurs that diverged early from the evolutionary lineage leading to modern birds. Within the Ceratosauria, some paleontologists proposed it to be most closely related to Genyodectes from Argentina, which shares the strongly elongated teeth. The geologically older genus Proceratosaurus from England, although originally described as a presumed antecedent of Ceratosaurus, was later found to be unrelated. Ceratosaurus shared its habitat with other large theropod genera including Torvosaurus and Allosaurus, and it has been suggested that these theropods occupied different ecological niches to reduce competition. Ceratosaurus may have preyed upon plant-eating dinosaurs, although some paleontologists suggested that it hunted aquatic prey such as fish. The nasal horn was probably not used as a weapon as was originally suggested by Marsh, but more likely was used solely for display.

Description

Ceratosaurus followed the body plan typical for large theropod dinosaurs.[1] A biped, it moved on powerful hind legs, while its arms were reduced in size. Specimen USNM 4735, the first discovered skeleton and holotype of Ceratosaurus nasicornis, was an individual 5.3 m (17 ft) or 5.69 m (18.7 ft) in length according to separate sources.[2]:115[3] Whether this animal was fully grown is not clear.[4]:66 Othniel Charles Marsh, in 1884, suggested that this specimen weighed about half as much as the contemporary Allosaurus.[5] In more recent accounts, this was revised to 418 kilograms (922 lb), 524 kg (1,155 lb), or 670 kg (1,480 lb).[6] Three additional skeletons discovered in the latter half of the 20th century were substantially larger. The first of these, UMNH VP 5278, was informally estimated by James Madsen to have been around 8.8 m (29 ft) long,[7] but was later estimated at 7 m (23 ft) in length.[8] Its weight was calculated at 980 kg (2,160 lb), 452 kg (996 lb), and 700 kg (1,540 lb) in separate works.[3][8][9] The second skeleton, MWC 1, was somewhat smaller than UMNH VP 5278 and might have been 275 kg (606 lb) in weight.[9] The third, yet undescribed, specimen BYUVP 12893 was claimed to be the largest yet discovered, although estimates have not been published.[10]:192 Another specimen (ML 352), discovered in Portugal in 2000, was estimated at 6 m (20 ft) in length and 600 kg (1,320 lb) in weight.[8]

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the spine of the Ceratosaurus nasicornis holotype. At least 20 vertebrae formed the neck and back in front of the sacrum. In the middle portion of the neck, the centra (bodies) of the vertebrae were as long as they were tall, while in the front and rear portions of the neck, the centra were shorter than their height. The upwards projecting neural spines were comparatively large, and in the dorsal (back) vertebrae, were as tall as the vertebral centra were long. The sacrum, consisting of six fused sacral vertebrae, was arched upwards, with its vertebral centra strongly reduced in height in its middle portion, as is the case in some other ceratosaurians.[4]:55–58 The tail comprised around 50 caudal vertebrae and was about half of the animal's total length; in the holotype, it was estimated at 2.84 m (9.33 ft).[5][2]:115 The tail was deep from top to bottom due to its high neural spines and elongated chevrons, bones located below the vertebral centra. As in other dinosaurs, it counterbalanced the body and contained the massive caudofemoralis muscle, which was responsible for forward thrust during locomotion, pulling the upper thigh backwards when contracted.[4]:55–58

The scapula (shoulder blade) was fused with the coracoid, forming a single bone without any visible demarcation between the two original elements.[4]:58 The C. nasicornis holotype was found with an articulated left fore limb including an incomplete manus (hand). Although disarticulated during preparation, a cast had been made of the fossil beforehand to document the original relative positions of the bones. Carpal bones were not known from any specimen, leading some authors to suggest that they were lost in the genus. In a 2016 paper, Matthew Carrano and Jonah Choiniere suggested that one or more cartilaginous (not bony) carpals were probably present, as indicated by a gap present between the forearm bones and the metacarpals, as well as by the surface texture within this gap seen in the cast.[11] In contrast to most more-derived theropods, which showed only three digits on each manus (digits I–III), Ceratosaurus retained four digits, with digit IV reduced in size. The first and fourth metacarpals were short, while the second was slightly longer than the third. The metacarpus and especially the first phalanges were proportionally very short, unlike in most other basal theropods. Only the first phalanges of digits II, III, and IV are preserved in the holotype; the total number of phalanges and unguals (claw bones) is unknown. The anatomy of metacarpal I indicates that phalanges had originally been present on this digit, as well. The pes (foot) consisted of three weight-bearing digits, numbered II–IV. Digit I, which in theropods is usually reduced to a dewclaw that does not touch the ground, is not preserved in the holotype. Marsh, in his original 1884 description, assumed that this digit was lost in Ceratosaurus, but Charles Gilmore, in his 1920 monograph, noted an attachment area on the second metatarsal demonstrating the presence of this digit.[2]:112

Uniquely among theropods, Ceratosaurus possessed small, elongated, and irregularly formed osteoderms (skin bones) along the midline of its body. Such osteoderms have been found above the neural spines of cervical vertebrae 4 and 5, as well as caudal vertebrae 4 to 10, and probably formed a continuous row that might have extended from the base of the skull to most of the tail. As suggested by Gilmore in 1920, their position in the rock matrix likely reflects their exact position in the living animal. The osteoderms above the tail were found separated from the neural spines by 25 mm (0.98 in) to 38 mm (1.5 in), possibly accounting for skin and muscles present in between, while those of the neck were much closer to the neural spines. Apart from the body midline, the skin contained additional osteoderms, as indicated by a 58 mm (2.3 in) by 70 mm (2.8 in) large, roughly quadrangular plate found together with the holotype; the position of this plate on the body is unknown.[2]:113–114 Specimen UMNH VP 5278 was also found with a number of osteoderms, which have been described as amorphous in shape. Although most of these ossicles were found at most 5 m apart from the skeleton, they were not directly associated with any vertebrae, unlike in the C. nasicornis holotype, so their original position on the body cannot be inferred from this specimen.[12]:32

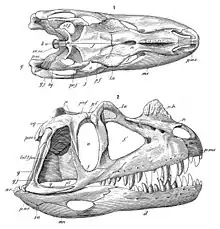

Skull

The skull was quite large in proportion to the rest of its body.[1] It measures 55 cm (22 in) in length in the C. nasicornis holotype, measured from the tip of the snout to the occipital condyle, which connects to the first cervical vertebra.[2]:88 The width of this skull is difficult to reconstruct, as it is heavily distorted, and Gilmore's 1920 reconstruction was later found to be too wide.[13] The fairly complete skull of specimen MWC 1 was estimated to have been 60 cm (24 in) in length and 16 cm (6.3 in) in width; this skull was somewhat more elongated than that of the holotype.[12]:3 The back of the skull was more lightly built than in some other larger theropods due to extensive skull openings, yet the jaws were deep to support the proportionally large teeth.[3]:277 The lacrimal bone formed not only the back margin of the antorbital fenestra, a large opening between eye and bony nostril, but also part of its upper margin, unlike in members of the related Abelisauridae. The quadrate bone, which was connected to the lower jaw at its bottom end to form the jaw joint, was inclined so that the jaw joint was displaced backwards in relation to the occipital condyle. This also led to a broadening of the base of the lateral temporal fenestra, a large opening behind the eyes.[4]:53

The most distinctive feature was a prominent horn situated on the skull midline behind the bony nostrils, which was formed from fused protuberances of the left and right nasal bones.[2]:82 Only the bony horn core is known from fossils—in the living animal, this core would have supported a keratinous sheath. While the base of the horn core was smooth, its upper two-thirds were wrinkled and lined with groves that would have contained blood vessels when alive. In the holotype, the horn core is 13 cm (5.1 in) long and 2 cm (0.79 in) wide at its base, but quickly narrows to only 1.2 cm (0.47 in) further up; it is 7 cm (2.8 in) in height.[2]:82 It is longer and lower in the skull of MWC 1.[12]:3 In the living animal, the horn would likely have been more elongated due to its keratinous sheath.[14] Behind the nasal horn, the nasal bones formed an oval groove; both this groove and the nasal horn serve as features to distinguish Ceratosaurus from related genera.[10]:192 In addition to the large nasal horn, Ceratosaurus possessed smaller, semicircular, bony ridges in front of each eye, similar to those of Allosaurus. These ridges were formed by the lacrimal bones.[9] In juveniles, all three horns were smaller than in adults, and the two halves of the nasal horn core were not yet fused.[15]

The premaxillary bones, which formed the tip of the snout, contained merely three teeth on each side, less than in most other theropods.[4]:52 The maxillary bones of the upper jaw were lined with 15 blade-like teeth on each side in the holotype. The first eight of these teeth were very long and robust, but from the ninth tooth onward they gradually decrease in size. As typical for theropods, they featured finely serrated edges, which in the holotype contained some 10 denticles per 5 mm (0.20 in).[2]:92 Specimen MWC 1 merely showed 11 to 12, and specimen UMNH VP 5278 12 teeth in each maxilla; the teeth were more robust and more recurved in the latter specimen.[12]:3,27 In all specimens, the tooth crowns of the upper jaws were exceptionally long. In specimen UMNH VP 5278, they measured up to 9.3 cm (3.7 in) in length, which is equal to the minimum height of the lower jaw. In the holotype, they are 7 cm (2.8 in) in length, which even surpasses the minimum height of the lower jaw. In other theropods, a comparable tooth length is only known from the possibly closely related Genyodectes.[16] In contrast, several members of the Abelisauridae feature very short tooth crowns.[4]:92 In the holotype, each half of the dentary, the tooth-bearing bone of the mandible, was equipped with 15 teeth, which are, however, poorly preserved. Both specimens MWC 1 and UMNH VP 5278 show only 11 teeth in each dentary, which were, as shown by the latter specimen, slightly straighter and less sturdy than those of the upper jaw.[12]:3,21

History of discovery

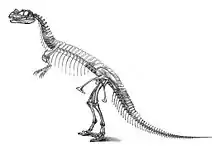

Holotype specimen of C. nasicornis

The first specimen, the holotype USNM 4735, was discovered and excavated by farmer Marshall Parker Felch in 1883 and 1884.[17] Found in articulation, with the bones still connected to each other, it was nearly complete, including the skull. Significant missing parts include an unknown number of vertebrae; all but the last ribs of the trunk; the humeri (upper arm bones); the distal finger bones of both hands; most of the right fore limb; most of the left hind limb; and most of the feet.[2]:77 The specimen was found encased in hard sandstone; the skull and spine had been heavily distorted during fossilization.[2]:2,114 The site of discovery, located in the Garden Park area north of Cañon City, Colorado, and known as the Felch Quarry 1, is regarded as one of the richest fossil sites of the Morrison Formation. Numerous dinosaur fossils had been recovered from this quarry even before the discovery of Ceratosaurus, most notably a nearly complete specimen of Allosaurus (USNM 4734) in 1883 and 1884.[2]:7,114

After excavation, the specimen was shipped to the Peabody Museum of Natural History in New Haven, where it was studied by Marsh, who described it as the new genus and species Ceratosaurus nasicornis in 1884.[5][2]:114 The name Ceratosaurus may be translated as "horn lizard" (from Greek κερας/κερατος, keras/keratos—"horn" and σαυρος/sauros—"lizard"),[7] and nasicornis with "nose horn" (from Latin nasus—"nose" and cornu—"horn").[18] Given the completeness of the specimen, the newly described genus was at the time the best-known theropod discovered in America. In 1898 and 1899, the specimen was transferred to the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, together with many other fossils originally described by Marsh. Only part of this material was fully prepared when it arrived in Washington; subsequent preparation lasted from 1911 to the end of 1918. Packaging and shipment from New Haven to Washington caused some damage to the Ceratosaurus specimen.[2]:2,114 In 1920, Charles Gilmore published an extensive redescription of this and the other theropod specimens received from New Haven, including the nearly complete Allosaurus specimen recovered from the same quarry.[2]:2

In an 1892 paper, Marsh published the first skeletal reconstruction of Ceratosaurus, which depicts the animal at 22 ft (6.7 m) in length and 12 ft (3.7 m) in height.[1] As noted by Gilmore in 1920, the trunk was depicted much too long in this reconstruction, incorporating at least six dorsal vertebrae too many. This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of Charles R. Knight, but not published until 1920. A more accurate life reconstruction, published in 1901, was produced by Joseph M. Gleeson, again under Knight's supervision. The holotype was mounted by Gilmore in 1910 and 1911, and since then was exhibited at the National Museum of Natural History. Most early reconstructions show Ceratosaurus in an upright posture, with the tail dragging on the ground.[2]:115–116 Gilmore's mount of the holotype, in contrast, was ahead of its time:[3]:276 Inspired by the upper thigh bones, which were found angled against the lower leg, he depicted the mount as a running animal with a horizontal rather than upright posture and a tail that did not make contact with the ground. Because of the strong flattening of the fossils, Gilmore mounted the specimen not as a free-standing skeleton, but as a bas-relief within an artificial wall.[2]:114 With the bones being partly embedded in a plaque, scientific access was limited. In the course of the renovation of the museum's dinosaur exhibition between 2014 and 2019, the specimen was dismantled and freed from the encasing plaque.[19][20] In the new exhibition, which is set to open in 2019, the mount is planned to be replaced by a free-standing cast, and the original bones to be stored in the museum collection to allow full access for scientists.[20]

.jpg.webp)

Additional finds in North America

After the discovery of the holotype of C. nasicornis, a significant Ceratosaurus find was not made until the early 1960s, when paleontologist James Madsen and his team unearthed a fragmentary, disarticulated skeleton including the skull (UMNH VP 5278) in the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah. This find represents one of the largest-known Ceratosaurus specimens.[12]:21 A second, articulated specimen including the skull (MWC 1) was discovered in 1976 by Thor Erikson, the son of paleontologist Lance Erikson, near Fruita, Colorado.[7] A fairly complete specimen, it lacks lower jaws, forearms and gastralia. The skull, although reasonably complete, was found disarticulated and is strongly flattened sidewards. Although a large individual, it had not yet reached adult size, as indicated by open sutures between the skull bones.[12]:2–3 Scientifically accurate three-dimensional reconstructions of the skull for use in museum exhibits were produced using a complicated process including molding and casting of the individual original bones, correction of deformities, reconstruction of missing parts, assembly of the bone casts into their proper position, and painting to match the original color of the bones.[21]

Both the Fruita and Cleveland-Lloyd specimens were described by Madsen and Samuel Paul Welles in a 2000 monograph, with the Utah specimen being assigned to the new species C. dentisulcatus and the Colorado specimen to the new species C. magnicornis.[12] The name dentisulcatus refers to the parallel grooves present on the inner sides of the premaxillary teeth and the first three teeth of the lower jaw in that specimen; magnicornis points to the larger nasal horn.[12]:2,21 The validity of both species, however, was questioned in subsequent publications. Brooks Britt and colleagues, in 2000, claimed that the C. nasicornis holotype was in fact a juvenile individual, with the two larger species representing the adult state of a single species.[22] Oliver Rauhut, in 2003, and Matthew Carrano and Scott Sampson, in 2008, considered the anatomical differences cited by Madsen and Welles to support these additional species to represent ontogenetic (age-related) or individual variation.[23][10]:192

A further specimen (BYUVP 12893) was discovered in 1992 in the Agate Basin Quarry southeast of Moore, Utah, but still awaits description. The specimen, considered the largest known from the genus, includes the front half of a skull, seven fragmentary pelvic dorsal vertebrae, and an articulated pelvis and sacrum.[10]:192[12]:36 In 1999, Britt reported the discovery of a Ceratosaurus skeleton belonging to a juvenile individual. Discovered in Bone Cabin Quarry in Wyoming, it is 34% smaller than the C. nasicornis holotype and consists of a complete skull as well as 30% of the remainder of the skeleton including a complete pelvis.[15]

Besides these five skeletal finds, fragmentary Ceratosaurus remains have been reported from various localities from stratigraphic zones 2 and 4-6 of the Morrison Formation,[24] including some of the major fossil sites of the formation. Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, yielded an isolated right premaxilla (specimen number DNM 972); a large shoulder blade (scapulocoracoid) was reported from Como Bluff in Wyoming. Another specimen stems from the Dry Mesa Quarry, Colorado, and includes a left scapulocoracoid, as well as fragments of vertebrae and limb bones. In Mygatt Moore Quarry, Colorado, the genus is known from teeth.[12]:36

Finds outside North America

From 1909 to 1913, German expeditions of the Berlin Museum für Naturkunde uncovered a diverse dinosaur fauna from the Tendaguru Formation in German East Africa, in what is now Tanzania.[25] Although commonly considered the most important African dinosaur locality,[25] large theropod dinosaurs are only known through few and very fragmentary remains.[26] In 1920, German paleontologist Werner Janensch assigned several dorsal vertebrae from the quarry "TL" to Ceratosaurus, as Ceratosaurus sp. (of uncertain species). In 1925, Janensch named a new species of Ceratosaurus, C. roechlingi, based on fragmentary remains from the quarry "Mw" encompassing a quadrate bone, a fibula, fragmentary caudal vertebrae, and other fragments. This specimen stems from an individual substantially larger than the C. nasicornis holotype.[26]

In their 2000 monograph, Madsen and Welles confirmed the assignment of these finds to Ceratosaurus. In addition, they ascribed several teeth to the genus, which had originally been described by Janensch as a possible species of Labrosaurus, Labrosaurus (?) stechowi.[12] Other authors questioned the assignment of any of the Tendaguru finds to Ceratosaurus, noting that none of these specimens displays features diagnostic for that genus.[27][4]:66[10]:192[28] In 2011, Rauhut found both C. roechlingi and Labrosaurus (?) stechowi to be possible ceratosaurids, but found them to be not diagnostic at genus level and therefore designated them as nomina dubia (doubtful names).[28] In 1990, Timothy Rowe and Jacques Gauthier mentioned yet another Ceratosaurus species from Tendaguru, Ceratosaurus ingens, which purportedly was erected by Janensch in 1920 and was based on 25 isolated, very large teeth up to 15 cm (5.9 in) in length.[27][26] However, Janensch assigned this species to Megalosaurus, not to Ceratosaurus; therefore, this name might be a simple copying error.[12]:37[26] Rauhut, in 2011, showed that Megalosaurus ingens was not closely related to either Megalosaurus or Ceratosaurus, but possibly represents a carcharodontosaurid, instead.[28]

In 2000 and 2006, paleontologists led by Octávio Mateus described a find from the Lourinhã Formation in central-west Portugal (ML 352) as a new specimen of Ceratosaurus, consisting of a right femur (upper thigh bone), a left tibia (shin bone), and several isolated teeth recovered from the cliffs of Valmitão beach, between the municipalities Lourinhã and Torres Vedras.[29][30] The bones were found embedded in yellow to brown, fine-grained sandstones, which were deposited by rivers as floodplain deposits and belong to the lower levels of the Porto Novo Member, which is thought to be late Kimmeridgian in age. Additional bones of this individual (SHN (JJS)-65), including a left femur, a right tibia, and a partial left fibula (calf bone), were since exposed due to progressing cliff erosion. Although initially part of a private collection, these additional elements became officially curated after the private collection was donated to the Sociedade de História Natural in Torres Vedras, and were described in detail in 2015.[31] The specimen was ascribed to the species Ceratosaurus dentisulcatus by Mateus and colleagues in 2006.[30] A 2008 review by Carrano and Sampson confirmed the assignment to Ceratosaurus, but concluded that the assignment to any specific species is not possible at present.[10]:192 In 2015, Elisabete Malafaia and colleagues, who questioned the validity of C. dentisulcatus, assigned the specimen to Ceratosaurus aff. Ceratosaurus nasicornis.[31]

Other reports include a single tooth found in Moutier, Switzerland. Originally named by Janensch in 1920 as Labrosaurus meriani, the tooth was later assigned Ceratosaurus sp. (of unknown species) by Madsen and Welles.[12]:35–36 In 2008, Matías Soto and Daniel Perea described teeth from the Tacuarembó Formation in Uruguay, including a presumed premaxillary tooth crown. This shows vertical striations on its inner side and lacks denticles on its front edge; these features are, in this combination, only known from Ceratosaurus. The authors, however, stressed that an assignment to Ceratosaurus is infeasible as the remains are scant, and furthermore note that the assignment of the European and African material to Ceratosaurus has to be viewed with caution.[32] In 2020, Soto and colleagues described additional Ceratosaurus teeth from the same formation that further support their earlier interpretation.[33]

Classification

In his original description of the Ceratosaurus nasicornis holotype and subsequent publications, Marsh noted a number of characteristics that were unknown in all other theropods known at the time.[10]:185 Two of these features, the fused pelvis and fused metatarsus, were known from modern-day birds, and according to Marsh, clearly demonstrate the close relationship between the latter and dinosaurs.[34] To set the genus apart from Allosaurus, Megalosaurus, and coelurosaurs, Marsh made Ceratosaurus the only member of both a new family, the Ceratosauridae, and a new infraorder, the Ceratosauria.[10]:185 This was questioned in 1892 by Edward Drinker Cope, Marsh's rival in the Bone Wars, who argued that distinctive features such as the nasal horn merely showed that C. nasicornis was a distinct species, but were insufficient to justify a distinct genus. Consequently, he assigned C. nasicornis to the genus Megalosaurus, creating the new combination Megalosaurus nasicornis.[35]

Although Ceratosaurus was retained as a distinct genus in all subsequent analyses,[2]:76 its relationships remained controversial during the following century. Both the Ceratosauridae and Ceratosauria were not widely accepted, with only few and poorly known additional members identified. Over the years, separate authors classified Ceratosaurus within the Deinodontidae, the Megalosauridae, the Coelurosauria, the Carnosauria, and the Deinodontoidea.[12]:2 In his 1920 revision, Gilmore argued that the genus was the most basal theropod known from after the Triassic, so not closely related to any other contemporary theropod known at that time; it thus warrants its own family, the Ceratosauridae.[2]:76 It was not until the establishment of cladistic analysis in the 1980s, however, that Marsh's original claim of the Ceratosauria as a distinct group gained ground. In 1985, the newly discovered South American genera Abelisaurus and Carnotaurus were found to be closely related to Ceratosaurus. Gauthier, in 1986, recognized the Coelophysoidea to be closely related to Ceratosaurus, although this clade falls outside of Ceratosauria in most recent analyses. Many additional members of the Ceratosauria have been recognized since.[10]:185

The Ceratosauria split off early from the evolutionary line leading to modern birds, thus is considered basal within theropods.[36] Ceratosauria itself contains a group of derived (nonbasal) members of the families Noasauridae and Abelisauridae, which are bracketed within the clade Abelisauroidea, as well as a number of basal members, such as Elaphrosaurus, Deltadromeus, and Ceratosaurus. The position of Ceratosaurus within basal ceratosaurians is under debate. Some analyses considered Ceratosaurus as the most derived of the basal members, forming the sister taxon of the Abelisauroidea.[10]:187[37] Oliver Rauhut, in 2004, proposed Genyodectes as the sister taxon of Ceratosaurus, as both genera are characterized by exceptionally long teeth in the upper jaw.[16] Rauhut grouped Ceratosaurus and Genyodectes within the family Ceratosauridae,[16] which was followed by several later accounts.[38][39][40][14]

Shuo Wang and colleagues, in 2017, concluded that the Noasauridae were not nested within the Abelisauroidea as was previously assumed, but instead were more basal than Ceratosaurus. Because noasaurids had been used as a fix point to define the clades Abelisauroidea and Abelisauridae, these clades would consequently include many more taxa per definition, including Ceratosaurus. In a subsequent 2018 study, Rafael Delcourt accepted these results, but pointed out that, as a consequence, the Abelisauroidea would need to be replaced by the older synonym Ceratosauroidea, which was hitherto rarely used. For the Abelisauridae, Delcourt proposed a new definition that excludes Ceratosaurus, allowing for using the name its traditional sense. Wang and colleagues furthermore found that Ceratosaurus and Genyodectes form a clade with the Argentinian genus Eoabelisaurus.[40] Delcourt used the name Ceratosauridae to refer to this same clade, and suggested to define the Ceratosauridae as containing all taxa that are more closely related to Ceratosaurus than to the abelisaurid Carnotaurus.[14]

The following cladogram showing the relationships of Ceratosaurus is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Diego Pol and Oliver Rauhut in 2012:[38]

| Ceratosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A skull from the Middle Jurassic of England apparently displays a nasal horn similar to that of Ceratosaurus. In 1926, Friedrich von Huene described this skull as Proceratosaurus (meaning "before Ceratosaurus"), assuming that it was an antecedent of the Late Jurassic Ceratosaurus.[41] Today, Proceratosaurus is considered a basal member of the Tyrannosauroidea, a much more derived clade of theropod dinosaurs;[42] the nasal horn therefore would have had evolved independently in both genera.[10]:185 Oliver Rauhut and colleagues, in 2010, grouped Proceratosaurus within its own family, the Proceratosauridae. These authors also noted that the nasal horn is incompletely preserved, opening the possibility that it represented the foremost portion of a more extensive head crest, as seen in some other proceratosaurids such as Guanlong.[42]

Paleobiology

Ecology and feeding

Within the Morrison Formation, Ceratosaurus fossils are frequently found in association with those of other large theropods, including the megalosaurid Torvosaurus and the allosaurid Allosaurus. The Garden Park locality in Colorado contained, besides Ceratosaurus, fossils attributed to Allosaurus. The Dry Mesa Quarry in Colorado, as well as the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry and the Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, feature, respectively, the remains of at least three large theropods: Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus, and Torvosaurus.[13][43] Likewise, Como Bluff and nearby localities in Wyoming contained remains of Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus, and at least one large megalosaurid.[44] Ceratosaurus was a rare element of the theropod fauna; it is outnumbered by Allosaurus at an average rate of 7.5 to 1 in sites where they co-occur.[45]

Several studies attempted to explain how these sympatric species could have reduced direct competition. Donald Henderson, in 1998, argued that Ceratosaurus co-occurred with two separate potential species of Allosaurus, which he denoted as "morphs": a morph with a shortened snout, a high and wide skull, and short, backwards-projecting teeth, and a morph characterized by a longer snout, lower skull, and long, vertical teeth. Generally speaking, the greater the similarity between sympatric species regarding their morphology, physiology, and behavior, the more intense competition between these species will be. Henderson came to the conclusion that the short-snouted Allosaurus morph occupied a different ecological niche from both the long-snouted morph and Ceratosaurus: The shorter skull in this morph would have reduced bending moments occurring during biting, thus increased bite force, comparable to the condition seen in cats. Ceratosaurus and the other Allosaurus morph, though, had long-snouted skulls, which are better compared to those of dogs: The longer teeth would have been used as fangs to deliver quick, slashing bites, with the bite force concentrated at a smaller area due to the narrower skull. According to Henderson, the great similarities in skull shape between Ceratosaurus and the long-snouted Allosaurus morph indicate that these forms engaged in direct competition with each other. Therefore, Ceratosaurus might had been pushed out of habitats dominated by the long-snouted morph. Indeed, Ceratosaurus is very rare in the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry, which contains the long-snouted Allosaurus morph, but appears to be more common in both Garden Park and the Dry Mesa Quarry, in which it co-occurs with the short-snouted morph.[13]

Furthermore, Henderson suggested that Ceratosaurus could have avoided competition by preferring different prey items; the evolution of its extremely elongated teeth might have been a direct result of the competition with the long-snouted Allosaurus morph. Both species could also have preferred different parts of carcasses when acting as scavengers. The elongated teeth of Ceratosaurus could have served as visual signals facilitating the recognition of members of the same species, or for other social functions. In addition, the large size of these theropods would have tended to decrease competition, as the number of possible prey items increases with size.[13]

Foster and Daniel Chure, in a 2006 study, concurred with Henderson that Ceratosaurus and Allosaurus generally shared the same habitats and preyed upon the same types of prey, thus likely had different feeding strategies to avoid competition. According to these researchers, this is also evidenced by different proportions of the skull, teeth, and fore limb.[45] The distinction between the two Allosaurus morphs, however, was questioned by some later studies. Kenneth Carpenter, in a 2010 study, found that short-snouted individuals of Allosaurus from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry represent cases of extreme individual variation rather than a separate taxon.[46] Furthermore, the skull of USNM 4734 from the Garden Park locality, which formed the basis for Henderson's analysis of the short-snouted morph, was later found to have been reconstructed too short.[47]

In a 2004 study, Robert Bakker and Gary Bir suggested that Ceratosaurus was primarily specialized in aquatic prey such as lungfish, crocodiles, and turtles. As indicated by a statistical analysis of shed teeth from 50 separate localities in and around Como Bluff, teeth of both Ceratosaurus and megalosaurids were most common in habitats in and around water sources such as wet floodplains, lake margins, and swamps. Ceratosaurus also occasionally occurred in terrestrial localities. Allosaurids, however, were equally common in terrestrial and aquatic habitats. From these results, Bakker and Bir concluded that Ceratosaurus and megalosaurids must have predominantly hunted near and within water bodies, with Ceratosaurus also feeding on carcasses of larger dinosaurs on occasion. The researchers furthermore noted the long, low, and flexible body of Ceratosaurus and megalosaurids. Compared to other Morrison theropods, Ceratosaurus showed taller neural spines on the foremost tail vertebrae, which were vertical rather than inclined towards the back. Together with the deep chevron bones on the underside of the tail, they indicate a deep, "crocodile-like" tail possibly adapted for swimming. On the contrary, allosaurids feature a shorter, taller, and stiffer body with longer legs. They would have been adapted for rapid running in open terrain and for preying upon large herbivorous dinosaurs such as sauropods and stegosaurs, but as speculated by Bakker and Bir, seasonally switched to aquatic prey items when the large herbivores were absent.[44] However, this theory was challenged by Yun in 2019, suggesting Ceratosaurus was merely more capable of hunting aquatic prey than other theropods of the Morrison Formation then its contemporaries as opposed to being fully semiaquatic.[48]

In his 1986 popular book The Dinosaur Heresies, Bakker argued that the bones of the upper jaw were only loosely attached to the surrounding skull bones, allowing for some degree of movement within the skull, a condition termed cranial kinesis. Likewise, the bones of the lower jaw would have been able to move against each other, and the quadrate bone to swing outwards, spreading the lower jaw at the jaw joint. Taken together, these features would have allowed the animal to widen its jaws in order to swallow large food items.[49] In a 2008 study, Casey Holliday and Lawrence Witmer re-evaluated similar claims made for other dinosaurs, concluding that the presence of muscle-powered cranial kinesis cannot be proven for any dinosaur species, and was likely absent in most.[50]

Function of the nasal horn and osteoderms

In 1884, Marsh considered the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus to be a "most powerful weapon" for both offensive and defensive purposes, and Gilmore, in 1920, concurred with this interpretation.[5]:331[2]:82 The use of the horn as a weapon is now generally considered unlikely, however.[7] In 1985, David Norman believed that the horn was "probably not for protection against other predators," but might instead have been used for intraspecific combat among male ceratosaurs contending for breeding rights.[51] Gregory S. Paul, in 1988, suggested a similar function, and illustrated two Ceratosaurus engaged in a nonlethal butting contest.[3] In 1990, Rowe and Gauthier went further, suggesting that the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus was "probably used for display purposes alone" and played no role in physical confrontations.[27] If used for display, the horn likely would have been brightly colored.[9] A display function was also proposed for the row of osteoderms running down the body midline.[27]

Forelimb function

The strongly shortened metacarpals and phalanges of Ceratosaurus raise the question whether the manus retained the grasping function assumed for other basal theropods. Within the Ceratosauria, an even more extreme manus reduction can be observed in abelisaurids, where the forelimb lost its original function,[52] and in Limusaurus. In a 2016 paper on the anatomy of the Ceratosaurus manus, Carrano and Jonah Choiniere stressed the great morphological similarity of the manus with those of other basal theropods, suggesting that it still fulfilled its original grasping function, despite its shortening. Although only the first phalanges are preserved, the second phalanges would have been mobile, as indicated by the well-developed articular surfaces, and the digits would likely have allowed a similar degree of motion as in other basal theropods. As in other theropods other than abelisaurids, digit I would have been slightly turned in when flexed.[11]

Brain and senses

_-_AMNH_-_DSC06292.JPG.webp)

A cast of the brain cavity of the holotype was made under Marsh's supervision, probably during preparation of the skull, allowing Marsh to conclude that the brain "was of medium size, but comparatively much larger than in the herbivorous dinosaurs". The skull bones, however, had been cemented together afterwards, so the accuracy of this cast could not be verified by later studies.[5][2]:93

A second, well preserved braincase had been found with specimen MWC 1 in Fruita, Colorado, and was CT-scanned by paleontologists Kent Sanders and David Smith, allowing for reconstructions of the inner ear, gross regions of the brain, and cranial sinuses transporting blood away from the brain. In 2005, the researchers concluded that Ceratosaurus possessed a brain cavity typical for basal theropods, and similar to that of Allosaurus. The impressions for the olfactory bulbs, which house the sense of smell, are well-preserved. While similar to those of Allosaurus, they were smaller than in Tyrannosaurus, which is thought to have been equipped with a very keen sense of smell. The semicircular canals, which are responsible for the sense of balance and therefore allow for inferences on habitual head orientation and locomotion, are similar to those found in other theropods. In theropods, these structures are generally conservative, suggesting that functional requirements during locomotion have been similar across species. The foremost of the semicircular canals was enlarged, a feature generally found in bipedal animals. The orientation of the lateral semicircular canal indicates that the head and neck were held horizontally in neutral position.[53]

Fusion of metatarsals and paleopathology

The holotype of C. nasicornis was found with its left metatarsals II to IV fused together.[54] Marsh, in 1884, dedicated a short article to this at the time unknown feature in dinosaurs, noting the close resemblance to the condition seen in modern birds.[34] The presence of this feature in Ceratosaurus became controversial in 1890, when Georg Baur speculated that the fusion in the holotype was the result of a healed fracture. This claim was repeated in 1892 by Cope, while arguing that C. nasicornis should be classified as a species of Megalosaurus due to insufficient anatomical differences between these genera.[35] However, examples of fused metatarsals in dinosaurs that are not of pathological origin have been described since, including taxa more basal than Ceratosaurus.[54] Osborn, in 1920, explained that no abnormal bone growth is evident, and that the fusion is unusual, but likely not pathological.[2]:112 Ronald Ratkevich, in 1976, argued that this fusion had limited the running ability of the animal, but this claim was rejected by Paul in 1988, who noted that the same feature occurs in many fast-moving animals of today, including ground birds and ungulates.[3] A 1999 analysis by Darren Tanke and Bruce Rothschild suggested that the fusion was indeed pathological, confirming the earlier claim of Baur.[54] Other reports of pathologies include a stress fracture in a foot bone assigned to the genus,[55] as well as a broken tooth of an unidentified species of Ceratosaurus that shows signs of further wear received after the break.[54]

Paleoenvironment and paleobiogeography

All North American Ceratosaurus finds come from the Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sedimentary rocks in the western United States, and the most fertile source for dinosaur bones of the continent. According to radiometric dating, the age of the formation ranges between 156.3 million years old (Mya) at its base,[56] and 146.8 million years old at the top,[57] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. Ceratosaurus is known from Kimmeridgian and Tithonian strata of the formation.[4]:49 The Morrison Formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels, and floodplains.[58] This formation is similar in age to the Lourinhã Formation in Portugal and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania.[59]

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs.[60] Other dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods Koparion, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes, Allosaurus, and Torvosaurus; the sauropods Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus; and the ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Othnielia, Gargoyleosaurus, and Stegosaurus.[61] Allosaurus, which accounted for 70 to 75% of all theropod specimens, was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[43] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles like Dorsetochelys, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans such as Hoplosuchus, and several species of pterosaurs such as Harpactognathus and Mesadactylus. Shells of bivalves and aquatic snails are also common. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns and ferns (gallery forests) to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[62]

A partial Ceratosaurus specimen indicates the presence of the genus in the Portuguese Porto Novo Member of the Lourinhã Formation. Many of the dinosaurs of the Lourinhã Formation are the same genera as those seen in the Morrison Formation, or have a close counterpart.[59] Besides Ceratosaurus, the researchers also noted the presence of Allosaurus and Torvosaurus in the Portuguese rocks are primarily known from the Morrison, while Lourinhanosaurus has so far only been reported from Portugal. Herbivorous dinosaurs from the Porto Novo Member include, among others, the sauropods Dinheirosaurus and Zby, as well as the stegosaur Miragaia.[63][29][30] During the Late Jurassic, Europe had just been separated from North America by the still narrow Atlantic Ocean, and Portugal, as part of the Iberian Peninsula, was still separated from other parts of Europe. According to Mateus and colleagues, the similarity between the Portuguese and North American theropod faunas indicates the presence of a temporary land bridge, allowing for faunal interchange.[29][30] Malafaia and colleagues, however, argued for a more complex scenario, as other groups, such as sauropods, turtles, and crocodiles, show clearly different species compositions in Portugal and North America. Thus, the incipient separation of these faunas could have led to interchange in some but allopatric speciation in other groups.[31]

References

- Marsh, O.C. (1892). "Restorations of Claosaurus and Ceratosaurus". American Journal of Science. 44 (262): 343–349. Bibcode:1892AmJS...44..343M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-44.262.343. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107356040. S2CID 130216318.

- Gilmore, C.W. (1920). "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus" (PDF). Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 110 (110): 1–154. doi:10.5479/si.03629236.110.i. hdl:2027/uiug.30112032536010.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). "Ceratosaurs". Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster. pp. 274–279. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Marsh, O.C. (1884). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part VIII: The order Theropoda" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 27 (160): 329–340. Bibcode:1884AmJS...27..329M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-27.160.329. S2CID 131076004.

- Therrien, F.; Henderson, D.M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours … or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:mtibty]2.0.co;2.

- Glut, D.F. (1997). "Ceratosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. pp. 266–270. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Gargantuan to Minuscule: The Morrison Menagerie, Part II". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 162–242. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- Carrano, M.T.; Sampson, S.D. (2008). "The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 30068953.

- Carrano, M.T.; Choiniere, J. (2016). "New information on the forearm and manus of Ceratosaurus nasicornis Marsh, 1884 (Dinosauria, Theropoda), with implications for theropod forelimb evolution". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (2): –1054497. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1054497. S2CID 88089084.

- Madsen, J.H.; Welles, S.P. (2000). Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda): A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey. pp. 1–80. ISBN 978-1-55791-380-7.

- Henderson, D.M. (1998). "Skull and tooth morphology as indicators of niche partitioning in sympatric Morrison Formation theropods". Gaia (15): 219–226.

- Delcourt, Rafael (2018). "Ceratosaur palaeobiology: new insights on evolution and ecology of the southern rulers". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 9730. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.9730D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28154-x. PMC 6021374. PMID 29950661.

- Britt, B.B.; Miles, C.A.; Cloward, K.C.; Madsen, J.H. (1999). "A juvenile Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from Bone Cabin Quarry West (Upper Jurassic, Morrison Formation), Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (Supplement to No 3): 33A. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011202.

- Rauhut, O.W.M. (2004). "Provenance and anatomy of Genyodectes serus, a large-toothed ceratosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 894–902. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0894:paaogs]2.0.co;2.

- Brinkman, P.D. (2010). The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush. Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-226-07472-6.

- Simpson, D.P. (1979) [1854]. Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. pp. 153, 387. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- Jacqueline, T. (May 3, 2012). "David Koch Donates $35 Million to National Museum of Natural History for Dinosaur Hall". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- "The Good, Bad and Ugly: Dismantling Historic Fossil Displays, Part Two". Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- Tidwell, V. (1996). "Restoring crushed Jurassic dinosaur skulls for display". The Continental Jurassic. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin. 60.

- Britt, B.B.; Chure, D.J.; Holtz, T.R., Jr.; Miles, C.A.; Stadtman, K.L. (2000). "A reanalysis of the phylogenetic affinities of Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Dinosauria) based on new specimens from Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (suppl): 32A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2000.10010765. S2CID 220412294.

- Rauhut, O.W.M. (2003). "The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs". Special Papers in Palaeontology: 25.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- Zils, C.W.; Moritz, A.; Saanane, C. (1995). "Tendaguru, the most famous dinosaur locality of Africa. Review, survey and future prospects". Documenta Naturae. 97: 1–41.

- Janensch, W. (1925). "Die Coelurosaurier und Theropoden der Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas". Palaeontographica (in German). Supplement VIII: 1–100.

- Rowe, T.; Gauthier, J. (1990). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. pp. 151–168. ISBN 978-0-520-06726-4.

- Rauhut, O.W.M. (2011). "Theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 195–239.

- Mateus, O.; Antunes, M.T. (2000). "Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the Late Jurassic of Portugal". 31st International Geological Congress, Abstract Volume. Rio de Janeiro.

- Mateus, O.; Walen, A.; Antunes, M.T. (2006). "The large theropod fauna of the Lourinhã Formation (Portugal) and its similarity to the Morrison Formation, with a description of a new species of Allosaurus". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 36.

- Malafaia, E.; Ortega, F.; Escaso, F.; Silva, B. (October 3, 2015). "New evidence of Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal". Historical Biology. 27 (7): 938–946. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.915820. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 129349509.

- Soto, M.; Perea, D. (2008). "A ceratosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous of Uruguay". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (2): 439–444. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[439:acdtft]2.0.co;2.

- Soto, Matías; Toriño, Pablo; Perea, Daniel (November 1, 2020). "Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Ceratosauria) teeth from the Tacuarembó Formation (Late Jurassic, Uruguay)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 103: 102781. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102781. ISSN 0895-9811.

- Marsh, O.C. (1884). "On the united metatarsal bones of Ceratosaurus". American Journal of Science. 28 (164): 161–162. Bibcode:1884AmJS...28..161M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-28.164.161. S2CID 131737380.

- Cope, E.D. (1892). "On the Skull of the Dinosaurian Lælaps incrassatus Cope". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 30 (138): 240–245. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 983173.

- Hendrickx, C.; Hartman, S.A.; Mateus, O. (2015). "An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 12 (1): 1–73.

- Xu, X.; Clark, J.M.; Mo, J.; Choiniere, J.; Forster, C.A.; Erickson, G.M.; Hone, D.W.; Sullivan, C.; Eberth, D.A.; Nesbitt, S.; Zhao, Q. (2009). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7249): 940–944. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..940X. doi:10.1038/nature08124. PMID 19536256. S2CID 4358448.

- Pol, D.; Rauhut, O.W.M. (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1804): 3170–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660. PMC 3385738. PMID 22628475.

- Delcourt, R. (2017). "Revised morphology of Pycnonemosaurus nevesi Kellner & Campos, 2002 (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) and its phylogenetic relationships". Zootaxa. 4276 (1): 1–45. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4276.1.1. PMID 28610214.

- Wang, S.; Stiegler, J.; Amiot, R.; Wang, X.; Du, G.-H.; Clark, J.M.; Xu, X. (2017). "Extreme ontogenetic changes in a ceratosaurian theropod" (PDF). Current Biology. 27 (1): 144–148. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043. PMID 28017609. S2CID 441498.

- Huene, F.v. (1926). "On several known and unknown reptiles of the order Saurischia from England and France". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Serie 9 (17): 473–489. doi:10.1080/00222932608633437.

- Rauhut, O.W.M.; Milner, A.C.; Moore-Fay, S. (2010). "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic position of the theropod dinosaur Proceratosaurus bradleyi (Woodward, 1910) from the Middle Jurassic of England". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (1): 155–195. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00591.x.

- Foster, J.R. (2003). Paleoecological analysis of the vertebrate fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- Bakker, Robert T.; Bir, Gary (2004). "Dinosaur crime scene investigations: theropod behavior at Como Bluff, Wyoming, and the evolution of birdness". In Currie, P.J.; Koppelhus, E.B.; Shugar, M.A.; Wright, J.L. (eds.). Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 301–342. ISBN 978-0-253-34373-4.

- Foster, J.R.; Chure, D.J. (2006). "Hindlimb allometry in the Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur Allosaurus, with comments on its abundance and distribution". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36: 119–122.

- Carpenter, Kenneth (2010). "Variation in a population of Theropoda (Dinosauria): Allosaurus from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry (Upper Jurassic), Utah, USA". Paleontological Research. 14 (4): 250–259. doi:10.2517/1342-8144-14.4.250. S2CID 84635714.

- Carpenter, Kenneth; Paul, Gregory S. (2015). "Comment on Allosaurus Marsh, 1877 (Dinosauria, Theropoda): proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype for its type species Allosaurus fragilis Marsh, 1877". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 72: 1.

- Changyu Yun (2019). "Comments on the ecology of Jurassic theropod dinosaur Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) with critical reevaluation for supposed semiaquatic lifestyle". Volumina Jurassica. in press. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- Bakker, R.T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. PALAIOS. 2. William Morrow and Company. p. 523. Bibcode:1987Palai...2..523G. doi:10.2307/3514623. ISBN 978-0-688-04287-5. JSTOR 3514623.

- Holliday, C.M.; Witmer, L.M. (December 12, 2008). "Cranial kinesis in dinosaurs: intracranial joints, protractor muscles, and their significance for cranial evolution and function in diapsids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1073–1088. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1073. S2CID 15142387.

- Norman, D.B. (1985). "Carnosaurs". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Salamander Books Ltd. pp. 62–67. ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- Senter, P. (2010). "Vestigial skeletal structures in dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 280 (4): 60–71. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00640.x.

- Sanders, R.K.; Smith, D.K. (2005). "The endocranium of the theropod dinosaur Ceratosaurus studied with computer tomography". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50 (3).

- Molnar, R.E. (2001). "Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 337–363.

- Rothschild, B.; Tanke, D.H.; Ford, T.L. (2001). "Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 331–336.

- Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry – age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- Russell, D.A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- Mateus, O. (2006). "Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): A comparison". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 223–231.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- Chure, D.J.; Litwin, R.; Hasiotis, S.T.; Evanoff, E.; Carpenter, K. (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- Mateus, O.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P. (2014). "Zby atlanticus, a new turiasaurian sauropod (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (3): 618–634. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.822875. S2CID 59387149.

External links

Media related to Ceratosaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ceratosaurus at Wikimedia Commons