Althing

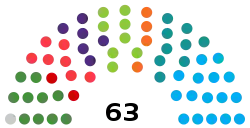

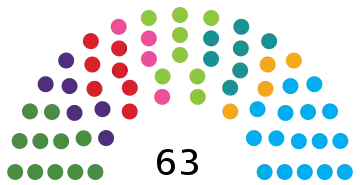

The Alþingi (Parliament in Icelandic, anglicised as Althingi or Althing) is the national parliament of Iceland. It is the oldest surviving parliament in the world.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] The Althing was founded in 930 at Þingvellir ("thing fields" or "assembly fields"), situated approximately 45 kilometres (28 mi) east of what later became the country's capital, Reykjavík. Even after Iceland's union with Norway in 1262, the Althing still held its sessions at Þingvellir until 1800, when it was discontinued. It was restored in 1844 and moved to Reykjavík, where it has resided ever since.[4] The present parliament building, the Alþingishús, was built in 1881, made of hewn Icelandic stone.[5] The unicameral parliament has 63 members, and is elected every four years based on party-list proportional representation.[6] The current speaker of the Althing is Steingrímur J. Sigfússon.

Icelandic Parliament Alþingi Íslendinga | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 63 |

| |

Political groups | Coalition government (33)

Opposition parties (30)

|

| Elections | |

| Party-list proportional representation | |

Last election | 28 October 2017 |

Next election | On or before 23 October 2021 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Alþingishúsið Austurvöllur 150 Reykjavík Iceland | |

| Website | |

| www | |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Iceland |

|

|

The constitution of Iceland provides for six electoral constituencies with the possibility of an increase to seven. The constituency boundaries and the number of seats allocated to each constituency are fixed by legislation. No constituency can be represented by fewer than six seats. Furthermore, each party with more than 5% of the national vote is allocated seats based on its proportion of the national vote in order that the number of members in parliament for each political party should be more or less proportional to its overall electoral support. If the number of voters represented by each member of the Althing in one constituency would be less than half of the comparable ratio in another constituency, the Icelandic National Electoral Commission is tasked with altering the allocation of seats to reduce that difference.[7]

Historical background

Foundation

The Althing claims to be the longest running parliament in the world.[1][2] Its establishment as an outdoor assembly or thing held on the plains of Þingvellir ('Thing Fields' or 'Assembly Fields') from about 930, laid the foundation for an independent national existence in Iceland. To begin with, the Althing was a general assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth, where the country's most powerful leaders (goðar) met to decide on legislation and dispense justice. All free men could attend the assemblies, which were usually the main social event of the year and drew large crowds of farmers and their families, parties involved in legal disputes, traders, craftsmen, storytellers and travellers. Those attending the assembly lived in temporary camps (búðir) during the session. The centre of the gathering was the Lögberg, or Law Rock, a rocky outcrop on which the Lawspeaker (lögsögumaður) took his seat as the presiding official of the assembly.[8] His responsibilities included reciting aloud the laws in effect at the time. It was his duty to proclaim the procedural law of the Althing to those attending the assembly each year.[9]

The Gulathing Law was adopted in 930 at the first Althing, introduced by Úlfljótr who had spent three years in Norway studying their laws. The Icelandic laws conferred a privileged status on the Danes, Swedes and Norwegians.[10]

According to Njáls saga, the Althing in 1000 declared Christianity as the official religion.[10] By the summer of 1000 the leaders of Iceland had agreed that prosecuting relatives for blaspheming the old gods was obligatory. Iceland was in the midst of unrest from the spread of Christianity that was introduced by travelers and missionaries sent by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason.[11] The outbreak of warfare in Denmark and Norway prompted Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi, a pagan and chieftain of the Althing, to propose "one law and one religion" to rule over the whole of Iceland, making baptism and conversion to Christianity required by law.[10]

Lögrétta

Public addresses on matters of importance were delivered at the Law Rock and there the assembly was called to order and dissolved. The Lögrétta, the legislative section of the assembly, was its most powerful institution. It comprised the 39 district Chieftains (goðar) plus nine additional members and the Lawspeaker. As the legislative section of the Althing, the Lögrétta took a stand on legal conflicts, adopted new laws and granted exemptions to existing laws. The Althing of old also performed a judicial function and heard legal disputes in addition to the spring assemblies held in each district. After the country had been divided into four-quarters around 965, a court of 36 judges (fjórðungsdómur) was established for each of them at the Althing. Another court (fimmtardómur) was established early in the 11th century. It served as a supreme court of sorts, and assumed the function of hearing cases left unsettled by the other courts. It comprised 48 judges appointed by the goðar of Lögrétta.[8]

Monarchy until 1800

When the Icelanders submitted to the authority of the Norwegian king under the terms of the "Old Covenant" (Gamli sáttmáli) in 1262, the function of the Althing changed. The organization of the Commonwealth came to an end and the rule of the country by goðar ceased. Executive power now rested with the king and his officials, the Royal Commissioners (hirðstjórar) and District Commissioners (sýslumenn). As before, the Lögrétta, now comprising 36 members, continued to be its principal institution and shared formal legislative power with the king. Laws adopted by the Lögrétta were subject to royal assent and, conversely, if the king initiated legislation, the Althing had to give its consent. The Lawspeaker was replaced by two legal administrators, called lögmenn.

Towards the end of the 14th century, royal succession brought both Norway and Iceland under the control of the Danish monarchy. With the introduction of absolute monarchy in Denmark, the Icelanders relinquished their autonomy to the Crown, including the right to initiate and consent to legislation. After that, the Althing served almost exclusively as a court of law until the year 1800.[8]

High Court: 1800–1845

The Althing was disbanded by royal decree in 1800. A new High Court, established by this same decree and located in Reykjavík, took over the functions of Lögrétta. The three appointed judges first convened in Hólavallarskóli on 10 August 1801. The High Court was to hold regular sessions and function as the court of highest instance in the country. It operated until 1920, when the Supreme Court of Iceland was established.[8]

Consultative assembly: 1845–1874

A royal decree providing for the establishment of a new Althing was issued on 8 March 1843. Elections were held the following year and the assembly finally met on 1 July 1845 in Reykjavík. Some Icelandic nationalists (the Fjölnir group) did not want Reykjavík as the location for the newly established Althing due to the perception that the city was too influenced by Danes. Jón Sigurðsson claimed that the situating of the Althing in Reykjavík would help make the city Icelandic.[12][8]

It comprised 26 members sitting in a single chamber. One member was elected in each of 20 electoral districts and six "royally nominated Members" were appointed by the king. Suffrage was, following the Danish model, limited to males of substantial means and at least 25 years of age, which to begin with meant only about 5% of the population. A regular session lasted four weeks and could be extended if necessary. During this period, the Althing acted merely as a consultative body for the Crown. It examined proposed legislation and individual members could raise questions for discussion. Draft legislation submitted by the government was given two readings, an introductory one and a final one. Proposals which were adopted were called petitions. The new Althing made a number of improvements to legislation and to the administration of the country.[8]

Legislative assembly from 1874

The Constitution of 1874 granted to the Althing joint legislative power with the Crown in matters of exclusive Icelandic concern. At the same time the National Treasury acquired powers of taxation and financial allocation. The king retained the right to veto legislation and often, on the advice of his ministers, refused to consent to legislation adopted by the Althing. The number of members of the Althing was increased to 36, 30 of them elected in general elections in eight single-member constituencies and 11 double-member constituencies, the other six appointed by the Crown as before. The Althing was now divided into an upper chamber, known as the Efri deild and a lower chamber, known as the Nedri deild.[13] Six elected members and the six appointed ones sat in the upper chamber, which meant that the latter could prevent legislation from being passed by acting as a bloc. Twenty-four elected representatives sat in the lower chamber. From 1874 until 1915 ad hoc committees were appointed. After 1915 seven standing committees were elected by each of the chambers. Regular sessions of the Althing convened every other year. A supplementary session was first held in 1886, and these became more frequent in the 20th century. The Althing met from 1881 in the newly built Parliament House. The Governor-General (landshöfðingi) was the highest representative of the government in Iceland and was responsible to the Advisor for Iceland (Íslandsráðgjafi) in Copenhagen.[8]

Home rule

A constitutional amendment, confirmed on 3 October 1903, granted the Icelanders home rule and parliamentary government. Hannes Hafstein was appointed as the Icelandic minister on 1 February 1904 who was answerable to parliament. The minister had to have the support of the majority of members of the Althing; in the case of a vote of no confidence, he would have to step down. Under the constitutional amendment of 1903, the number of members was increased by four, to a total of forty. Elections to the Althing had traditionally been public – voters declared aloud which of the candidates they supported. In 1908 the secret ballot was adopted, with ballot papers on which the names of the candidates were printed. A single election day for the entire country was at the same time made mandatory. When the Constitution was amended in 1915, the royally nominated members of the Althing were replaced by six national representatives elected by proportional representation for the entire country.[8]

Personal union

The Act of Union which took effect on 1 December 1918 made Iceland a state in personal union with the king of Denmark. It was set to expire after 25 years, when either state could choose to leave the union. The Althing was granted unrestricted legislative power. In 1920 the number of members of the Althing was increased to 42. Since 1945, the Althing has customarily assembled in the autumn. With the Constitutional Act of 1934 the number of members was increased by seven and the system of national representatives abolished in favour of one providing for eleven seats used to equalize discrepancies between the parties' popular vote and the number of seats they received in the Althing, raising the number of members of the Althing to 49. In 1934, the voting age was also lowered to 21. Further changes in 1942 provided for an additional three members and introduced proportional representation in the double-member constituencies. The constituencies were then 28 in number: 21 single-member constituencies; six double-member constituencies; and Reykjavík, which elected eight members. With the additional eleven equalization seats, the total number of members was thus 52.[8]

Republic

When Denmark was occupied by Germany on 9 April 1940 the union with Iceland was effectively severed. On the following day, the Althing passed two resolutions, investing the Icelandic cabinet with the power of Head of State and declaring that Iceland would accept full responsibility for both foreign policy and coastal surveillance. A year later the Althing adopted a law creating the position of Regent to represent the Crown. This position continued until the Act of Union was repealed, and the Republic of Iceland established, at a session of the Althing held at Þingvellir on 17 June 1944.

In 1959 the system of electoral districts was changed completely. The country was divided into eight constituencies with proportional representation in each, in addition to the previous eleven equalization seats. The total number of members elected was 60. In 1968, the Althing approved the lowering of the voting age to 20 years. A further amendment to the Constitution in 1984 increased the number of members to 63 and reduced the voting age to 18 years. By a constitutional amendment of June 1999, implemented in May 2003, the constituency system was again changed. The number of constituencies was cut from eight to six; constituency boundaries were to be fixed by law. Further major changes were introduced in the Althing in May 1991: the assembly now sits as a unicameral legislature. There are currently twelve standing committees.[8]

The Black Cone, Monument to Civil Disobedience

The Black Cone, Monument to Civil Disobedience is a memorial stone in Reykjavik, which is located opposite of the Icelandic Parliament building and was erected in 2012 to commemorate the third anniversary of the protests (“Pan Revolution”) during the crisis of 2008–2011. The monument is a stone almost two meters (six feet) high, split in half black cone. On the stone there is a plate with a quote in two languages (Icelandic and English) from the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (not from the original 1789, but from the expanded version of 1793 [1]), which is the most important document of the Great French Revolution and the history of the protection of human rights in general :

"When the government violates the rights of the people, an uprising is for every part of the people the most sacred of rights and the most necessary of duties." [8]

Recent elections

While elections may be held every four years, they can be held more frequently due to extenuating circumstances.

Results of 2017 general election

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independence Party | D | 49,543 | 25.2 | 16 | –5 | |||||

| Left-Green Movement | V | 33,155 | 16.9 | 11 | +1 | |||||

| Social Democratic Alliance | S | 23,652 | 12.1 | 7 | +4 | |||||

| Centre Party | M | 21,335 | 10.9 | 7 | New | |||||

| Progressive Party | B | 21,016 | 10.7 | 8 | 0 | |||||

| Pirate Party | P | 18,051 | 9.2 | 6 | –4 | |||||

| People's Party | F | 13,502 | 6.9 | 4 | +4 | |||||

| Reform Party | C | 13,122 | 6.7 | 4 | –3 | |||||

| Bright Future | A | 2,394 | 1.2 | 0 | –4 | |||||

| People's Front of Iceland | R | 375 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Dawn | T | 101 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 5,531 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Total | 201,777 | 100 | 63 | 0 | ||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 248,502 | 81.2 | – | – | ||||||

| Source: Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic) Iceland Monitor (in English) | ||||||||||

Members (1980s–present)

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 1983–1987

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 1987–1991

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 1991–1995

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 1995–99

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 1999–2003

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2003–07

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2007–09

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2009–13

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2013–16

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2016–17

- List of members of the parliament of Iceland, 2017–present

See also

- List of Speakers of the Althing

- List of Speakers of the Lower House of the Althing (until 1991 when the Althing became unicameral)

- List of Speakers of the Upper House of the Althing (until 1991 when the Althing became unicameral)

- List of parliaments of Iceland

- Constituencies of Iceland

Notes

References

- "A short history of Alþingi – the oldest parliament in the world". europa.eu. The European Union. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Meredith, Sam (28 October 2016). "World's oldest parliament poised for radical Pirates to takeover". CNBC. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- The High Court of Tynwald, The High Court of Tynwald (www.tynwald.org.im), retrieved 14 November 2011

- Sigurðardóttir, Heiða María; Emilsson, Páll Emil. "Hvenær var Alþingi stofnað?". visindavefur.is. Vísindavefurinn. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "ALÞINGISHÚSIÐ – ÁGRIP AF BYGGINGARSÖGU ÞESS". Morgunblaðið. 24 April 1949. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Álvarez-Rivera, Manuel. "Election Resources on the Internet: Elections to the Icelandic Althing (Parliament)". electionresources.org. Election Resources. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Stjórnarskipunarlög um breytingu á stjórnarskrá lýðveldisins Íslands, nr. 33/1944, með síðari breytingum". althingi.is. Alþingi Íslands. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Alþingi" (PDF). Althing. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Lögberg – the law rock". Þjóðgarðurinn á Þingvöllum. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Orfield, Lester B. (1953). The Growth of Scandinavian Law. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781584771807.

- Jochens, Jenny (1998). Women in Old Norse Society. Cornell University Press. p. 18.

- Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). The History of Iceland. pp. 206.

- Clements' Encyclopedia of World Governments. 8. John Clements Political Research, Inc. 1989. p. 162.

External links

| Look up Althing in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Althingi's English website

Media related to Alþingi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alþingi at Wikimedia Commons