Parliament of Tuvalu

The Parliament of Tuvalu (called Fale i Fono in Tuvaluan, or Palamene o Tuvalu) is the unicameral national legislature of Tuvalu.

Parliament of Tuvalu Fale i Fono | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

Prime Minister | Kausea Natano since 19 September 2019 |

Speaker | Samuelu Teo since 20 September 2019 |

| Structure | |

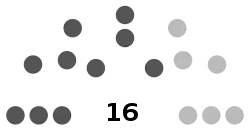

| Seats | 16 |

| |

Political groups | Government (10) |

| Elections | |

| Plurality voting | |

Last election | 2019 |

Next election | 2023 |

| Website | |

| https://tuvaluparadise.tv | |

| Footnotes | |

| * all candidates for Parliament officially stand as independents. | |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Tuvalu |

|

|

History

In 1886, an Anglo-German agreement partitioned the “unclaimed” central Pacific, leaving Nauru in the German sphere of influence, while Ocean Island and the future Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony (GEIC) wound up in the British sphere of influence. The Ellice Islands came under Britain's sphere of influence in the late 19th century, when they were declared a British protectorate by Captain Gibson R.N. of HMS Curacoa, between 9 and 16 October 1892 and joined with the Gilbert Islands. The Ellice Islands were administered as a British protectorate by a Resident Commissioner from 1892 to 1916 as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT), and from 1916 to 1974 as part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony (GEIC).

With the creation in 1970 of a Legislative Council where only 4 members were from Ellice Islands constituencies, the idea of a separation between the two archipelagoes became stronger. In 1974, the Ellicean voted by referendum for separate British dependency status. As a consequence Tuvalu separated from the Gilbert Islands which later became Kiribati.[1] Tuvalu became fully independent within the Commonwealth on 1 October 1978. On 5 September 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations.

The way in which legislation was created changed as Tuvalu evolved from a being a British protectorate to a British colony until it eventually became an independent country:[2]

- British protectorate of Gilbert and Ellice Islands – legislation was promulgated by High Commissioner of the Western Pacific;

- British colony of Gilbert and Ellice Islands - legislation was promulgated by the Resident Commissioner (later Governor) of Gilbert and Ellice Islands;

- British colony of Tuvalu - legislation was promulgated by the Governor of Tuvalu; and

- Tuvalu – when it became an independent state and a parliamentary democracy – legislation is enacted by the Fale i Fono, Parliament of Tuvalu, and becomes law following signature by the Governor-General of Tuvalu.

During the time of the British colony of Tuvalu until independence the parliament of Tuvalu was called the House of the Assembly or Fale i Fono. The parliament was first established when Tuvalu separated from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in 1976. Following independence in October 1978 the House of the Assembly was renamed officially the Fale i Fono (unofficially translated by Palamene o Tuvalu).[3]

The elections to the parliament — then called the House of the Assembly — immediately before independence was the 1977 Tuvaluan general election; with Toaripi Lauti being appointed as prime minister on 1 October 1977 with a Grandfather clause. The parliament was dissolved in July 1978 and thereafter the government of Toaripi Lauti was acting in a caretaker capacity only until the 1981 Tuvaluan general election was held.[3]

At the date of independence there were 12 members of the Parliament of Tuvalu.[4] The Electoral Act was amended in December 1999 to increase the membership of parliament from 12 to 15 MPs.[5] In August 2007 the Constitution was changed to increase the number of ministers from 5 to 7.[5][6]

Constitution

The Constitution of Tuvalu states that it is “the supreme law of Tuvalu” and that “all other laws shall be interpreted and applied subject to this Constitution”. It sets out the Principles of the Bill of Rights and the Protection of the Fundamental Rights and Freedoms.[7][8] In 1986, the Constitution adoption of independence was amended in order to give attention to Tuvaluan custom and tradition as well as the aspirations and values of the Tuvaluan people.[9][10] The changes placed greater emphasis on Tuvaluan community values rather than Western concepts of individual entitlement.[9]

Section 4 of the Laws of Tuvalu Act 1987 describes the Law of Tuvalu as being derived from: the Constitution, the law enacted by the Parliament of Tuvalu, customary law, the common law of Tuvalu and every applied law. ‘Applied law’ is defined in Section 7 of that Act as “imperial enactments which have effect as part of the law of Tuvalu”.[10]

Political culture

Summoning

The summoning of Parliament is covered by Section 116 of the Constitution, which states that “subject to this section, Parliament shall meet at such places in Tuvalu, and at such times, as the Head of State, acting in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet, appoints.” The question as to whether the Governor General has the power to summon Parliament without, or in disregard of the advice of Cabinet and, if so, the circumstances which could allow the use of that power, was considered in Amasone v Attorney General.[11]

The exercise of political judgment in the calling of by-elections and the summoning of parliament was again tested in 2013. Prime minister Willy Telavi delayed calling a by-election following the death of a member from Nukufetau until the opposition took legal action, which resulted in the High Court ordering the prime minister to issue a notice to hold the by-election.[12][13] The 2013 Nukufetau by-election was won by the opposition candidate. The Tuvaluan constitutional crisis continued until August 2013. The governor-general Iakoba Italeli then proceeded to exercise his reserve powers to order Mr Telavi's removal and appoint Enele Sopoaga as interim prime minister.[14][15] The Governor General also ordered that Parliament sit on Friday 2 August to allow a vote of no-confidence in Mr Telavi and his government.[16]

Member responsibilities

The role of the member of the Parliament of Tuvalu in the parliamentary democracy by established in the Constitution, and the ability of a Falekaupule (the traditional assembly of elders of each island) to direct an MP as to their conduct as a member, was considered in Nukufetau v Metia. The Falekaupule of Nukufetau directed Lotoala Metia, the elected member of parliament, as to which group of members he should join and when this directive was not followed the Falekaupule ordered Metia to resign as a member of parliament. When Falekaupule attempted to enforce these directives through legal action, the High Court determined that the Constitution is structured around the concept of a parliamentary democracy;[17] and that “[o]ne of the most fundamental aspects of parliamentary democracy is that, whilst a person is elected to represent the people of the district from which he is elected, he is not bound to act in accordance with the directives of the electorate either individually or as a body. He is elected because a majority of the voters regard him as the candidate best equipped to represent them and their interests in the government of their country. He is bound by the rules of parliament and answerable to parliament for the manner in which he acts. Should he lose the confidence of the electorate, he cannot be obliged to resign and he can only be removed for one of the reasons set out in sections 96 to 99 of the Constitution.”[18]

No parties

There are no formal parties in Tuvalu. The political system is based on personal alliances and loyalties derived from clan and family connections.[3][5][19] The Parliament of Tuvalu is rare among national legislatures in that it is non-partisan in nature. It does tend to have both a distinct government and a distinct opposition, but members often cross the floor between the two groups, resulting in a number of mid-term changes of government in recent years, such as followed the 2010 Tuvaluan general election.[5][19] Maatia Toafa was elected prime minister soon after the election, however on 24 December 2010, he lost office after a motion of no confidence, carried by eight votes to seven,[20] which had the result that a new ministry was formed by Willy Telavi.[21] Telavi retained a majority support in parliament following the 2011 Nui by-election, however the 2013 Nukufetau by-election was won by the opposition candidate, which resulted in the loss of his majority.[22] A constitutional crisis developed when Telavi took the position that, under the Constitution of Tuvalu, he was only required to convene parliament once a year, and was thus under no obligation to summon it until December 2013.[23] However he was forced to call parliament following the intervention of the governor-general. On 2 August 2013 Willy Tevali faced a motion of no confidence in the parliament.[24] On 4 August the parliament elected Enele Sopoaga as prime minister.[24][25] In 2015 the parliament was dissolved with a general election set down for March.[26]

Composition

A candidate for parliament must be a citizen of Tuvalu of a minimum age of 21 years. Voting in Tuvalu is not compulsory. At 18 years of age, Tuvaluans are eligible to be added to the electoral rolls.[3] The parliament has 15 members, each of whom serve a four-year term.[27] Each member is elected by popular vote in one of eight island-based constituencies: seven islands elect 2 members each, while Nukulaelae is represented by 1 member. The residents of Niulakita, the smallest island, are included in the electoral roll for Niutao.

The parliament is responsible for the selection the Prime Minister of Tuvalu from among their ranks and also the Speaker of Parliament by secret ballot. The Speaker presides over the parliament. The ministers that form the Cabinet are appointed by the governor-general on the advice of the prime minister. The Attorney-General sits in parliament, but does not vote: the parliamentary role of the Attorney-General is purely advisory.[3] The current Attorney-General is Eselealofa Apinelu.

Any member of parliament may introduce legislation into parliament, but in practice, as in most partisan systems, this occurs mainly at the behest of the governing Cabinet. Legislation undergoes first, second and third readings before being presented to the Governor-General of Tuvalu for assent, as in other Westminster systems. One notable variation, however, is that legislation is constitutionally required to be presented to local governments (falekaupules) for review after the first reading; they may then propose amendments through their local member of parliament.[5]

The under-representation of women in the Tuvalu parliament was considered in a report commissioned by the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat in 2005,[28] In May 2010, a consultation entitled “Promoting Women in Decision Making” was held in Funafuti, as parliament at that time had no women MPs. The outcome was a recommendation for the introduction of two new seats, to be reserved for women.[29] This followed the example of Papua New Guinea, which had only one female MP at that time, and whose Parliament was considering a bill to introduce 22 seats reserved for women. The Tuvaluan Ministry for Home Affairs, which has responsibility for women’s affairs, stated that steps would be taken to consider the recommendation.[30]

Throughout the history of the parliament three women have been elected: Naama Maheu Latasi, from 1989 to 1997; Pelenike Isaia from 2011 to 2015; and Dr Puakena Boreham from 2015. Pelenike Isaia was elected in a by-election in the Nui constituency in 2011 that followed the death of her husband Isaia Italeli, who was a member of parliament.[31] Pelenike Isaia was not re-elected in the 2015 general election. Dr Puakena Boreham was elected to represent Nui in the 2015 general election.[32][33]

Elections

The most recent general election was held on 9 September 2019.[34] In the Nukufetau electorate the caretaker prime minister, Enele Sopoaga, was returned to parliament, however Satini Manuella, Taukelina Finikaso and Maatia Toafa, who were ministers, were not returned. Seven new members of Parliament were elected.[34]

Following the 2019 Tuvaluan general election, on 19 September 2019, the members of parliament elected Kausea Natano from Funafuti as prime minister with a 10-6 majority.[35][36] Samuelu Teo was elected as Speaker of the Parliament of Tuvalu.[37]

Elected members

| Constituency | Members | Faction |

|---|---|---|

| Funafuti | Kausea Natano | Government |

| Simon Kofe | Government | |

| Nanumaga | Monise Lafai | Opposition |

| Minute Alapati Taupo | Government | |

| Nanumea | Ampelosa Manoa Tehulu | Government |

| Timi Melei | Government | |

| Niutao | Katepu Laoi | Government |

| Samuelu Teo | Government | |

| Nui | Puakena Boreham | Opposition |

| Mackenzie Kiritome | Opposition | |

| Nukufetau | Enele Sopoaga | Opposition |

| Fatoga Talama | Opposition | |

| Nukulaelae | Seve Paeniu | Government |

| Namoliki Sualiki | Opposition | |

| Vaitupu | Isaia Vaipuna Taape | Government |

| Nielu Meisake | Government |

See also

References

- McIntyre, W. David (2012). "The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands" (PDF). 7 (1) Island Studies Journal. pp. 135–146.

- "PACLII". Government of Tuvalu. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- "Palamene o Tuvalu (Parliament of Tuvalu)" (PDF). Inter-Parliamentary Union. 1981. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Palamene o Tuvalu (Parliament of Tuvalu)". Inter-Parliamentary Union. 1998. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Paulson Panapa & Jon Fraenkel (2008). "The Loneliness of the Pro-Government Backbencher and the Precariousness of Simple Majority Rule in Tuvalu" (PDF). Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Palamene o Tuvalu (Parliament of Tuvalu)". Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2002. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "The Constitution of Tuvalu". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- "The Constitution of Tuvalu". Tuvalu Online. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Levine, Stephen (1992). "Constitutional Change in Tuvalu". Australian Journal of Political Science. 27 (3): 492–509. doi:10.1080/00323269208402211.

- Farran, Sue (2006). "Obstacle to Human Rights? Considerations from the South Pacific" (PDF). Journal of Legal Pluralism: 77–105. doi:10.1080/07329113.2006.10756592. S2CID 143975144.

- "Amasone v Attorney General [2003] TVHC 4; Case No 24 of 2003 (6 August 2003)". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "Attorney General, In re Application under Section 131(1) of the Constitution of Tuvalu [2014] TVHC 15; Civil Case 1.2013 (24 May 2013)". PACLII. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Matau, Robert (June 2013). "Tuvalu's high court orders by-election to be held". Island Business. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21.

- Matau, Robert (1 August 2013). "GG appoints Sopoaga as Tuvalu's caretaker PM". Island Business. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- AFP, Report (2 August 2013). "Dismissal crisis rocks Tuvalu". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Cooney, Campbell (1 August 2013). "Tuvalu government faces constitutional crisis". Australia News Network. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Nukufetau v Metia [2012] TVHC 8; Civil Case 2.2011 (11 July 2012)". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "Nukufetau v Metia [2012] TVHC 8; [30]". PACLII. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hassall, Graham (2006). "The Tuvalu General Election 2006". Democracy and Elections project, Governance Program, University of the South Pacific. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Nominations open for new Tuvalu PM". Radio New Zealand International. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Willie Telavi the new prime minister in Tuvalu". Radio New Zealand International. 24 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Matau, Robert (5 August 2013). "Tuvalu's Opposition waiting to hear from GG". Islands Business. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Parliament needs one yearly meeting only says defiant Tuvalu PM", Radio New Zealand International, 2 July 2013

- Cooney, Campbell (4 August 2013). "Tuvalu parliament elects new prime minister". Australia News Network. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Cooney, Campbell (5 August 2013). "Sopoaga elected new PM in Tuvalu". Radio Australia. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Two unopposed seats for Tuvalu election". Radio New Zealand. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- "Palamene o Tuvalu (Parliament of Tuvalu)". Inter-Parliamentary Union. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Susie Saitala Kofe and Fakavae Taomia (2005). "Advancing Women's Political Participation in Tuvalu" (PDF). A Research Project Commissioned by the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS). Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Women Need Support to Overcome Barriers Entering Parliament", Solomon Times, 11 May 2010

- "Support for introducing reserved seats into Tuvalu Parliament" Archived 2014-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, May 13, 2010

- "Tuvalu PM to remain in power", ABC Radio Australia (audio), 25 August 2011

- "Cabinet position could await new Tuvalu MP". Radio New Zealand. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- Pua Pedro & Semi Malaki (1 April 2015). "One female candidate make it through the National General Election" (PDF). Fenui News. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Tahana, Jamie (10 September 2019). "Tuvalu elections: large turnover for new parliament". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Tuvalu has elected a new Prime Minister - Hon. Kausea Natano". 19 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "10 MPs will vote on Thursday to oust the caretaker government in Tuvalu". 16 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Kausea Natano new PM of Tuvalu; Sopoaga ousted". 19 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.