Parliament of Singapore

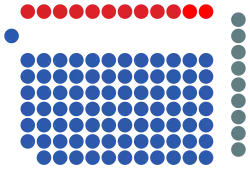

The Parliament of the Republic of Singapore and the President jointly make up the legislature of Singapore. Largely based from the Westminster system, the Parliament is unicameral and is made up of Members of Parliament (MPs) who are elected, as well as Non-constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs) and Nominated Members of Parliament (NMPs) who are appointed. Following the 2020 general election, 93 MPs and two NCMPs were elected to the 14th Parliament. Nine NMPs will usually be appointed.

| 14th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Established | 9 August 1965 |

| Preceded by | Legislative Assembly of Singapore |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 104 seats 93 MPs 2 NCMPs 9 NMPs |

| |

Political groups |

|

Length of term | Maximum of 5 years |

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post (with general tickets in GRCs) | |

Last election | 10 July 2020 |

Next election | By 24 November 2025 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Parliament House Downtown Core, Singapore | |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Singapore |

|

|

The Speaker of Parliament has overall charge of the administration of Parliament and its secretariat, and presides over parliamentary sittings. The Leader of the House is an MP appointed by the Prime Minister to arrange government business and the legislative programme of Parliament, while the Leader of the Opposition is the MP who leads the largest political party not in the government. Some of Parliament's work is carried out by select committees made up of small numbers of MPs. Standing select committees are permanently constituted to fulfil certain duties, and ad hoc select committees are established from time to time to deal with matters such studying the details of bills. In addition, selected backbenchers of the ruling People's Action Party sit on Government Parliamentary Committees that examine the policies, programmes and proposed legislation of government ministries.

The main functions of Parliament are lawmaking, controlling the nation's finances, and ensuring ministerial accountability. Parliament convenes when it is in session. The first session of a particular Parliament commences when Parliament meets after being formed following a general election. A session ends when Parliament is prorogued (temporarily suspended) or dissolved. The maximum term of each Parliament is five years, after which Parliament automatically dissolves. A general election must then be held within three months.

The quorum for a Parliamentary sitting is one quarter of the total number of MPs, not including the Speaker. An MP begins a debate by moving a motion and delivering an opening speech explaining the reasons for the motion. The Speaker (or chairman, if Parliament is in committee) then puts the motion in the form of a question, following which other MPs may debate the motion. After that, the mover may exercise a right of reply. When the debate is closed, the Speaker puts the question on the motion to the House and calls for a vote. Voting is generally done verbally, and whether the motion is carried depends on the Speaker's personal assessment of whether more MPs have voted for than against the motion. MPs' votes are only formally counted if an MP claims a division.

Parliament convened at the Old Parliament House between 1955 and 1999, before moving into a newly constructed Parliament House on 6 September 1999.

Terminology

The term Parliament is used in a number of different senses. First, it refers to the institution made up of a group of people (Members of Parliament or MPs) who are elected to discuss matters of state. Secondly, it can mean each group of MPs voted into office following a general election. In this sense, the First Parliament of the independent Republic of Singapore sat from 8 December 1965 to 8 February 1968. The current Parliament, which started on 24 August 2020, is the fourteenth.[1][2]

Parliament is sometimes used loosely to refer to Parliament House, which is the seat of the Parliament of Singapore.

History

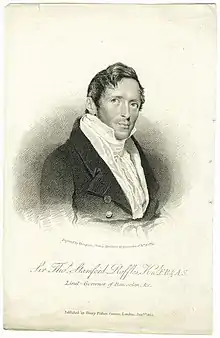

On 6 February 1819, Sultan Hussein Shah and the Temenggung of Johor, Abdul Rahman Sri Maharajah, entered into an agreement with Sir Stamford Raffles for the British East India Company (EIC) to establish a "factory" or trading post on the island of Singapore. Raffles, who was Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu, Indonesia), placed Singapore under Bencoolen's jurisdiction.[3] As Bencoolen was itself a factory subordinate to the Bengal Presidency in British India,[4] only the Governor-General in Council in Bengal was authorized to enact laws for Singapore. On 24 June 1824 Singapore was removed from Bencoolen's control and, together with Malacca, formally transferred to the EIC.[5] This made them subordinate to Fort William in Calcutta (now Kolkata), the capital of the Bengal Presidency.[6] By a treaty of 19 November 1824, the Sultan and Temenggung of Johor ceded Singapore to the EIC. In 1826, the company constituted Malacca, Prince of Wales Island (now Penang) and Singapore into the Presidency of the Straits Settlements[7] with Penang as the capital.[8] The general power to make laws for the Straits Settlements remained with the Supreme Government in India and the Parliament of the United Kingdom; Penang's legislative power was limited to making rules and regulations relating to duties and taxes that the Settlement was empowered to levy.[9][10]

On 20 June 1830, as a cost-cutting measure, the Straits Settlements ceased to be a separate presidency and were placed under the Bengal Presidency's control by the EIC. In 1833, the Government of India Act[11] passed by the British Parliament created a local government for the whole of India made up of the Governor-General and his counsellors. They were collectively known as the Governor-General of India in Council and had the sole power to pass laws for the Straits Settlements. However, India's slow response to problems in the Settlements such as the ineffective court system and the lack of Straits representation in the Indian legislative council prompted merchants and other prominent people to call for the Settlements to be governed directly by the Colonial Office in the United Kingdom. Finally, on 1 April 1867 the Straits Settlements were separated from the Government of India and became a Crown colony.[12]

Under letters patent dated 4 February 1867, the Straits Settlements were granted a colonial constitution in the usual form. The Governor of the Straits Settlements ruled with the help of an executive council and a legislative council. The executive council was made up of the governor, the commanding officer of the troops in the Straits, and six senior officials (including the colonial secretary, lieutenant-governor of Penang, attorney-general and colonial engineer). The legislative council, in which legislative authority was vested, consisted of the executive council and the chief justice (together known as the official members) and four unofficial members nominated by the governor. As the unofficial members were outnumbered by the official members, they and the governor (who had a casting vote) had effective control of the council. Legislation was generally initiated by the Governor, and he had the power to assent to or veto bills. During legislative debates, official members were required to support the governor, but the unofficials could speak and vote as they wished. In 1924, the system was changed such that two unofficial members of the legislative council were nominated by the governor to sit on the Executive Council. In addition, the number of members of the legislative council was increased to 26, with equal numbers of officials and unofficials. The governor retained his casting vote. The Penang and European chambers of commerce each nominated one unofficial, while the governor nominated the others on an ethnic basis: five Europeans, including one each from Penang and Malacca, three Chinese British subjects, one Malay, one Indian and one Eurasian. This system remained in place until Singapore fell to the Japanese in 1942 during World War II.[13]

Following the Second World War, the Straits Settlements were disbanded and Singapore became a Crown colony in its own right.[14] The reconstituted Legislative Council consisted of four ex officio members from the Executive Council, seven official members, between two and four unofficial members, and nine elected members. The Governor continued to hold a veto and certain reserved powers over legislation. As there was a majority of official members in the council, the constitution was criticized for not allowing locals to play an effective role in public affairs. Governor Franklin Charles Gimson therefore formed a Reconstitution Committee that proposed, among other things, recommended that the council should be made up of four ex officio members; five officials; four nominated unofficials; three representatives nominated by the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and the Indian Chamber of Commerce to represent European, Chinese and Indian economic interests; and six members to be elected by universal suffrage. For the first time, non-officials held a majority in the legislature. A new constitution embodying these arrangements came into force on 1 March 1948[15] and Singapore's first democratic elections were held on 20 March that year. Three out of the six elected seats were won by the Progressive Party.[16]

In 1951 three more elected seats were created in the council.[17] In February 1954, the Rendel Constitutional Commission under the chairmanship of Sir George William Rendel, which had been appointed to comprehensively review the constitution of the Colony of Singapore, rendered its report. Among other things, it recommended that the Legislative Council be transformed into a legislative assembly of 32 members made up of three ex officio official members holding ministerial posts, four nominated unofficial members, and 25 elected unofficial members. In addition, a Council of Ministers would be created, composed of the three ex officio members and six elected members appointed by the Governor on the recommendation of the Leader of the House, who would be the leader of the largest political party or coalition of parties having majority support in the legislature. The recommendation was implemented in 1955.[18] In the general election held that year, the Labour Front took a majority of the seats in the Assembly, and David Saul Marshall became the first Chief Minister of Singapore. Major problems with the Rendel Constitution were that the Chief Minister and Ministers' powers were ill-defined, and that the official members retained control of the finance, administration, and internal security and law portfolios. This led to confrontation between Marshall, who saw himself as a Prime Minister governing the country, and the Governor, Sir John Fearns Nicoll, who felt that important decisions and policies should remain with himself and the officials.[19][20]

In 1956, members of the Legislative Assembly held constitutional talks with the Colonial Office in London. The talks broke down as Marshall did not agree to the British Government's proposal for the casting vote on a proposed Defence Council to be held by the British High Commissioner to Singapore, who would only exercise it in an emergency. Marshall resigned as Chief Minister in June 1956, and was replaced by Lim Yew Hock. The following year, Lim led another delegation to the UK for further talks on self-government. This time, agreement was reached on the composition of an Internal Security Council. Other constitutional arrangements were swiftly settled in 1958, and on 1 August the United Kingdom Parliament passed the State of Singapore Act 1958,[21] granting the colony full internal self-government. Under Singapore's new constitution, which came into force on 3 June 1959,[22] the Legislative Assembly consisted of 51 elected members and the Governor was replaced by the Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State), who had power to appoint as Prime Minister the person most likely to command the authority of the Legislative Assembly, and other Ministers of the Cabinet on the Prime Minister's advice.[23] In the 1959 general elections, the People's Action Party swept to power with 43 out of the 51 seats in the Assembly, and Lee Kuan Yew became the first Prime Minister of Singapore.[24]

In 1963, Singapore gained independence from Britain through merger with Malaysia. In the federal legislature, Singapore was allocated 15 out of 127 seats. Under its new State Constitution,[25] Singapore kept its own executive government and legislative assembly. However, with effect from 9 August 1965, Singapore left Malaysia and became a fully independent republic. On separation from Malaysia, the Singapore Government retained its legislative powers, and the Parliament of Malaysia gave up all power to make laws for Singapore.[26] Similarly, the Republic of Singapore Independence Act 1965,[27] passed on 22 December 1965 and made retrospective to 9 August, declared that the legislative powers of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (Supreme Head of the Federation) and Parliament of Malaysia ceased and vested in the president and the Parliament of Singapore respectively.[28]

Composition

Members of Parliament

The Parliament of Singapore is unicameral – all Members of Parliament (MPs) make up a single chamber, and there is no senate or upper house. At present, the effect of the Constitution of Singapore and other legislation is that there can be a maximum of 105 MPs. Ninety-three are elected by the people while up to 12 Non-constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs)[29] and up to nine Nominated Members of Parliament (NMPs) may be appointed.[30] After the 2020 general election, 93 MPs were elected[31] and two NCMPs were appointed (or, in the terms of the Parliamentary Elections Act,[32] declared elected) to Parliament.[33]

Elected Members

As of the 2020 general election, for the purpose of parliamentary elections, Singapore was divided into 31 electoral divisions (also known as constituencies).[34][35] The names and boundaries of the divisions are specified by the Prime Minister by notification in the Government Gazette.[36] Fourteen of these divisions are Single Member Constituencies (SMCs) and 17 are Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs). GRCs were introduced in 1991 for the purpose of ensuring representation of the Malay, Indian and other minority communities in Parliament.[37] In a GRC, all the candidates must either be members of the same political party or independent candidates standing as a group,[38] and at least one of the candidates must be a person belonging to the Malay, Indian or some other minority community.[39] The president, at Cabinet's direction, declares the electoral divisions that are to be GRCs; the number of candidates (not less than three but not more than six) to stand for Parliament in each GRC; and whether the minority candidates in each GRC are to be from the Malay, Indian, or other minority communities.[40] At all times there must be at least eight divisions that are not GRCs,[41] and the number of Members of Parliament (MPs) to be returned by all GRCs cannot be less than a quarter of the total number of MPs to be returned at a general election.[42]

Each electoral division returns one MP, or if it is a GRC the number of MPs designated for the constituency by the president, to serve in Parliament.[43] A GRC can have a minimum of three and a maximum of six MPs.[44] In other words, a successful voter's single vote in an SMC sends to Parliament one MP, and in a GRC sends a slate of between three and six MPs depending on how many have been designated for that GRC. At present, SMCs return to Parliament 14 MPs and GRCs 79 MPs. All elected MPs are selected on a simple plurality voting ("first past the post") basis.[45] A person is not permitted to be an MP for more than one constituency at the same time.[46]

In the last general election in 2020, the incumbent People's Action Party (PAP) won 83 of the 93 seats, but lost Hougang SMC, Aljunied GRC, and the newly created Sengkang GRC to the Workers' Party of Singapore (WP). This was the first time more than one GRC had been won by an opposition party. With the Workers' Party securing ten elected seats in Parliament, this was the best opposition parliamentary result since the nation's independence. Out of the current 93 elected MPs, 26 (about 27.96%) are female.[47] This was an increase from the figure of about 22.47% for the 13th Parliament (before the resignation of Halimah Yacob), in which 20 of the 89 elected MPs were women.[48]

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People's Action Party | 1,527,491 | 61.23 | 83 | 0 | |

| Workers' Party | 279,922 | 11.22 | 10 | +4 | |

| Progress Singapore Party | 253,996 | 10.18 | 0 | New | |

| Singapore Democratic Party | 111,054 | 4.45 | 0 | 0 | |

| National Solidarity Party | 93,653 | 3.75 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peoples Voice | 59,183 | 2.37 | 0 | New | |

| Reform Party | 54,599 | 2.19 | 0 | 0 | |

| Singapore People's Party | 37,998 | 1.52 | 0 | 0 | |

| Singapore Democratic Alliance | 37,237 | 1.49 | 0 | 0 | |

| Red Dot United | 31,260 | 1.25 | 0 | New | |

| People's Power Party | 7,489 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | |

| Independents | 655 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2,494,537 | 100.00 | 93 | +4 | |

| Valid votes | 2,494,537 | 98.20 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 45,822 | 1.80 | |||

| Total votes | 2,540,359 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 2,651,435 | 95.81 | |||

| Source: Singapore Elections | |||||

Non-constituency Members of Parliament

Non-constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs) were introduced in 1984 to ensure the representation in Parliament of a minimum number of MPs from a political party or parties not forming the Government.[49] The number of NCMPs in Parliament is 12 less the number of opposition MPs elected.[50]

To be eligible to become an NCMP, a candidate must have polled not less than 15% of the total number of valid votes in the electoral division contested by him or her.[51] The unelected opposition candidate who receives the highest percentage of votes is entitled to be declared the first NCMP, followed by other opposition candidates in descending order according to the percentages of votes polled by them.[52] If any candidates have an equal percentage of votes and the number of such candidates exceeds the number of NCMPs to be declared elected, the NCMPs are determined as follows:[53]

- If all the candidates are from the same group of candidates nominated in a GRC, the Returning Officer overseeing the election in the relevant electoral division will inform the group of the number of candidates in the group to be declared elected as NCMPs. The members of the group must determine among themselves who shall be elected and inform the Returning Officer within seven days.

- In other cases, or if the Returning Officer is not notified of a decision by the group of candidates referred to in the preceding paragraph, the Returning Officer will determine the NCMPs to be deemed elected by drawing lots.

Following the 2020 general election, since ten opposition MPs were elected to Parliament, the law provides for up to two NCMPs to be declared elected. The seats were taken up by Hazel Poa and Leong Mun Wai of the Progress Singapore Party, who were part of the team that contested in West Coast GRC in the election and were the best performing opposition candidates that did not win in their constituency.[33][54]

Nominated Members of Parliament

In 1990, the Constitution was amended to provide for the appointment of up to nine Nominated Members of Parliament (NMPs) to Parliament.[55] The change was prompted by the impression that the existing two Opposition MPs had not adequately expressed significant alternative views held outside Parliament, and that the scheme would allow the Government to take advantage of the expertise of Singaporeans who were not able or prepared to take part in elections and look after constituencies.[56]

Formerly, within six months after Parliament first met after any general election, it had to decide whether there would be any NMPs during the term of that Parliament.[57] With effect from 1 July 2010,[58] such a decision became unnecessary as NMPs were made a permanent feature in Parliament.[59][60] A special select committee of Parliament chaired by the Speaker of Parliament is established, and invites the general public to submit names of persons who may be considered for nomination by the Committee.[61] From these names, the special select committee then nominates not more than nine persons for appointment by the president as NMPs.[62] The persons to be nominated must have rendered distinguished public service, or have brought honour to Singapore, or have distinguished themselves in the field of arts and letters, culture, the sciences, business, industry, the professions, social or community service or the labour movement; and in making any nomination, the special select committee must have regard to the need for NMPs to reflect as wide a range of independent and non-partisan views as possible.[63] Subject to rules on the tenure of MPs in general, NMPs serve for a term of two and a half years.[64] The first two NMPs sworn in on 20 December 1990 were cardiologist Professor Maurice Choo and company executive Leong Chee Whye.[65]

NMPs can participate in all parliamentary debates, but cannot vote on any motion relating to:[66]

- bills to amend the Constitution;

- Supply Bills, Supplementary Supply Bills or Final Supply Bills, which authorize the spending of public funds by the Government;

- Money Bills, which deal with various finance-related matters;[67]

- votes of no confidence in the Government; and

- removal of the president from office.

Qualifications

Persons are qualified to be elected or appointed as Members of Parliament if:[68]

- they are Singapore citizens;

- they are 21 years of age or above on the day of nomination for election;

- their names appear in a current register of electors;

- they are resident in Singapore at the date of nomination and have been so resident for an aggregate period of not less than ten years before that date;

- they are able, with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable them to take an active part in Parliamentary proceedings, to speak and, unless incapacitated by blindness or some other physical cause, to read and write at least one of the following languages: English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil; and

- they are not otherwise disqualified from being MPs under Article 45 of the Constitution.

Article 45 provides that persons are not qualified to be MPs if:[69]

- they are and have been found or declared to be of unsound mind;

- they are undischarged bankrupts;

- they hold offices of profit;

- having been nominated for election to Parliament or the office of President or having acted as election agent to a person so nominated, they have failed to lodge any return of election expenses required by law within the time and in the manner required;

- they have been convicted of an offence by a court of law in Singapore or Malaysia and sentenced to imprisonment for a term of not less than one year or to a fine of not less than S$2,000 and have not received a free pardon;[70]

- they have voluntarily acquired the citizenship of, or exercised rights of citizenship in, a foreign country or has made a declaration of allegiance to a foreign country;[71] or

- they are disqualified under any law relating to offences in connection with elections to Parliament or the office of President by reason of having been convicted of such an offence or having in proceedings relating to such an election been proved guilty of an act constituting such an offence.

A person's disqualification for having failed to properly lodge a return of election expenses or having been convicted of an offence[72] may be removed by the president. If the president has not done so, the disqualification ceases at the end of five years from the date when the return was required to be lodged or, as the case may be, the date when the person convicted was released from custody or the date when the fine was imposed. In addition, a person is not disqualified for acquiring or exercising rights of foreign citizenship or declared allegiance to a foreign country if he or she did so before becoming a Singapore citizen.[73]

Tenure of office

If an MP becomes subject to any disqualification specified in paragraph 1, 2, 5 or 7 above[74] and it is open to the Member to appeal against the decision, the Member immediately ceases to be entitled to sit or vote in Parliament or any committee of it. However, he or she is not required to vacate his or her seat until the end of 180 days beginning with the date of the adjudication, declaration or conviction, as the case may be.[75] After that period, the MP must vacate his or her seat if he or she continues to be subject to one of the previously mentioned disqualifications.[76] Otherwise, the MP is entitled to resume sitting or voting in Parliament immediately after ceasing to be disqualified.[77]

The above rules do not operate to extend the term of service of an NMP beyond two and a half years.[78]

MPs also cease to hold office when Parliament is dissolved, or before that if their seats become vacant for one of the following reasons:[79]

- if they cease to be Singapore citizens;

- if they cease to be members of, or are expelled or resign from, the political parties they stood for in the election;

- if they resign their seats by writing to the Speaker;

- if they have been absent without the Speaker's permission from all sittings of Parliament or any Parliamentary committee to which they have been appointed for two consecutive months in which the sittings are held;

- if they become subject to any of the disqualifications in Article 45;

- if Parliament exercises its power of expulsion on them; or

- if, being NMPs, their terms of service expire.

On 14 February 2012, Yaw Shin Leong, then MP for Hougang Single Member Constituency, was expelled from the Workers' Party for refusing to explain allegations of marital infidelity against him. After he notified the Clerk of Parliament that he did not intend to challenge his ouster, the Speaker stated that his Parliamentary seat had been vacated with effect from the date of expulsion, and that a formal announcement would be made in Parliament on the matter on 28 February.[80]

NMPs must vacate their Parliamentary seats if they stand as candidates for any political party in an election or if they are elected as MPs for any constituencies.[81] A person whose seat in Parliament has become vacant may, if qualified, again be elected or appointed as a Member of Parliament from time to time.[82] Any person who sits or votes in Parliament, knowing or having reasonable ground for knowing they are not entitled to do so, is liable to a penalty not exceeding $200 for each day that they sit or vote.[83]

Decisions on disqualification questions

Any question whether any MP has vacated his or her seat, or, in the case of a person elected as Speaker or Deputy Speaker from among non-MPs, he or she ceases to be a citizen of Singapore or becomes subject to any of the disqualifications specified in Article 45,[84] is to be determined by Parliament, the decision of which on the matter is final.[85]

This does not mean that an MP retains his or her Parliamentary seat despite being under some disqualification until Parliament has made a formal decision on the matter. On 10 November 1986, the MP for Anson, Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam of the Workers' Party of Singapore, lost an appeal against a conviction for making a false statement in a declaration and was sentenced to one month's imprisonment and a fine of $5,000. Further applications and appeals in the criminal proceedings to the High Court, Court of Appeal and the Privy Council (then Singapore's highest court) were dismissed.[86] On 9 December, the Speaker of Parliament made a statement in the House that Jeyaretnam had ceased to be an MP with effect from 10 November by virtue of having been convicted of an offence and sentenced to a fine of not less than $2,000. Jeyaretnam did not object to the statement at the time. Under Article 45(2) of the Constitution, he was disqualified to be an MP until five years had elapsed from the date the fine was imposed. Jeyaretnam subsequently applied to court for a declaration that, among other things, he had not ceased to be an MP in 1986 and that the Speaker's statement had been ineffective because Parliament itself had not determined that he had vacated his seat. On 9 July 1990, the High Court ruled that Jeyaretnam had ceased to be an MP by operation of law and that no separate determination by Parliament had been necessary.[87]

Remuneration and pensions

MPs receive a monthly allowance,[88] a non-pensionable annual allowance (commonly known as the 13th month pay), and an annual variable component that is paid in July and December each year.[89] The monthly allowance is 56% of the salary of an Administrative Service officer at the SR9 grade – the entry grade for Singapore's top civil servants – which is itself benchmarked at the salary of the 15th person aged 32 years from six professions: banking, law, engineering, accountancy, multinational companies and local manufacturers. In 1995, the monthly allowance was S$8,375 ($100,500 per year).[90] The allowance was revised in 2000 to $11,900 ($142,800 per year).[91]

In 2007, it was announced that civil service salaries had lagged behind those in the private sector and required revision. MPs' salaries were therefore increased in phases. In 2007, the monthly allowance was revised to $13,200, raising the annual sum to $158,400. A gross domestic product (GDP) bonus payable to civil servants was also extended to MPs to link their annual remuneration to the state of the economy. They would receive no bonus if GDP growth was 2% or less, one month's bonus if the GDP grew at 5%, and up to two months' bonus if the GDP growth reached or exceeded 8%. MPs' allowances to engage legislative and secretarial assistants were also increased from $1,000 to $1,300 and from $350 to $500 respectively.[90] With effect from January 2008, each MP received another increase of his or her allowance package to $13,710 a month, bringing it to $225,000 per year.[92] Subsequently, in 2012, MP's allowances were reduced to $192,500 per annum.[93]

Persons who have reached the age of 50 years and retired as MPs and who have served in this capacity for not less than nine years may be granted a pension for the rest of their lives. The annual amount payable is 1⁄30 of the person's highest annual salary for every completed year of service and 1⁄360 for every uncompleted year, up to a ceiling of two-thirds of the Member's annual salary.[94] No person has an absolute right to compensation for past services or to any pension or gratuity, and the president may reduce or withhold pensions and gratuities upon an MP's conviction for corruption.[95]

Speaker of Parliament

The Speaker has overall charge of the administration of Parliament and its secretariat. His or her official role is to preside over parliamentary sittings,[96] moderating debates and making decisions based on the Standing Orders of Parliament for the proper conduct of parliamentary business. The Speaker does not participate in debates, but can abstain or vote for or against a motion if he or she is entitled to do so by virtue of being an MP. The Speaker also acts as the representative of Parliament in its external relations, welcoming visiting dignitaries and representing Parliament at national events and overseas visits.[97]

The Speaker must be elected when Parliament first meets after any general election, before it proceeds to deal with any other business. Similarly, whenever the office of Speaker is vacant for some reason other than a dissolution of Parliament, no business must be transacted other than the election of a person to fill that office.[98] The Speaker may be elected from among the MPs who are not Ministers or Parliamentary Secretaries, but even a person who is not an MP can be chosen. Nonetheless, a candidate who is not an MP must possess the qualifications to stand for election as an MP.[99] The Speaker's salary may not be reduced while he is in office.[100]

The Speaker may at any time resign his or her office by writing to the Clerk of Parliament. The Speaker must vacate his or her office

- when Parliament first meets after a general election;

- in the case of a Speaker who is also an MP, if he ceases to be an MP for a reason other than a dissolution of Parliament, or if he or she is appointed to be a Minister or a Parliamentary Secretary; or

- in the case of a Speaker elected from among persons who are not MPs, if he or she ceases to be a Singapore citizen or becomes subject to any of the disqualifications stated in Article 45.[84]

Parliament shall from time to time elect two Deputy Speakers. Whenever the office of a Deputy Speaker is vacant for a reason other than a dissolution of Parliament, Parliament shall, as soon as is convenient, elect another person to that office.[101] As with the Speaker, a Deputy Speaker may be elected either from among the MPs who are neither Ministers nor Parliamentary Secretaries or from among persons who are not MPs, but those in the latter category must have the qualifications to be elected an MP.[102] Deputy Speakers may resign their office in the same way as the Speaker, and must vacate their office in the same circumstances.[103]

If there is no one holding the office of Speaker, or if the Speaker is absent from a sitting of Parliament or is otherwise unable to perform the functions conferred by the Constitution, these functions may be performed by a Deputy Speaker. If there is no Deputy Speaker or he or she is likewise absent or unable to perform the functions, they may be carried out by some other person elected by Parliament for the purpose.[104]

The current Speaker of Parliament is Tan Chuan-Jin, who was last appointed Minister for Social and Family Development, with effect from 11 September 2017.[105]

Leader of the House

The Leader of the House is an MP appointed by the Prime Minister to arrange government business and the legislative programme of Parliament. He or she initiates motions concerning the business of the House during sittings, such as actions to be taken on procedural matters and extending sitting times.[106]

The current Leader of the House is Indranee Rajah[107] who has assumed this office on 14 August 2020. She is assisted by Deputy Leader Zaqy Mohammed.

Leader of the Opposition

In parliamentary systems of government on the Westminster model, the Leader of the Opposition is the MP who is the leader of the largest opposition party able and prepared to assume office if the Government resigns. This political party often forms a Shadow Cabinet, the members of which serve as opposition spokespersons on key areas of government.[108] This is taken into consideration by the Speaker when seats in Parliament are allocated, and during a debate the MP is often given the privilege of being one of the first non-Government MPs to speak.[109]

Singapore presently does not have a shadow cabinet in Parliament as the People's Action Party (PAP) has held an overwhelming majority of the seats in the House since it came to power in 1959. However, at the 1991 general election four opposition politicians were elected to Parliament: Chiam See Tong, Cheo Chai Chen and Ling How Doong from the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP), and Low Thia Khiang from the Workers' Party of Singapore (WP).[110] On 6 January 1992 during a Parliamentary debate on the election of the Speaker of Parliament, the Leader of the House Wong Kan Seng said that he proposed to treat Chiam, then the SDP's secretary-general, as the "unofficial Leader of the Opposition" and that the House should give him "due courtesy and precedence among Opposition MPs". He likened the situation to that in the Legislative Assembly of Singapore in 1955 when the PAP won three out of four contested seats, and Lee Kuan Yew was de facto Leader of the Opposition.[111] After Chiam was replaced by Ling as secretary-general of the SDP in 1993, the latter was referred to as the unofficial Leader of the Opposition.[112]

In the 2006 general election, Chiam and Low retained their seats, and Sylvia Lim from the WP was appointed an NCMP. The prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, referred to Low, who is the WP's secretary-general, as Leader of the Opposition during a debate in the House on 13 November 2006.[113] However, following the 2011 general election, Low announced he would not be accepting the title. He said: "Either you have a leader of the opposition, or you do not have it. There's no need to have an unofficial leader of the opposition." He also noted that the title appeared "derogatory" to him because it implied that "you only qualify as unofficial".[109] Pritam Singh took over as the Leader of Opposition upon being elected as WP's new secretary-general on 8 April 2018.

Following the 2020 general election, at which the Workers' Party won ten seats, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that party leader Pritam Singh would be designated as the official Leader of the Opposition and "will be provided with appropriate staff support and resources to perform his duties".[114]

Party whip

The primary role of a party whip in Parliament is to enforce party discipline and ensure that sufficient numbers of MPs from his or her political parties attend sittings of the House and vote along party lines. From time to time, a whip may "lift the whip" and allow MPs to vote according to their consciences.[115] In March 2009, the whip was lifted for PAP MPs during debates on amendments to the Human Organ Transplant Act[116] that would permit financial compensation to be paid to organ donors.[117] A whip also schedules the MPs that will speak for each item of Parliamentary business.

The present government whip is Janil Puthucheary, assisted by deputy government whip, Sim Ann.[118] The party whip for the Workers' Party is Pritam Singh, and the deputy party whip is Sylvia Lim.

Committees

Select committees

A select committee is a committee made up of a small number of MPs appointed to deal with particular areas or issues. Standing select committees (that is, permanently constituted committees) are either chaired by the Speaker of Parliament or an MP appointed to the position, and its members are usually up to seven MPs appointed by Parliament in a manner that ensures that, so far as is possible, the balance between the Government benches and the Opposition benches in Parliament is reflected in the Committee. Parliament may also appoint ad hoc select committees to deal with other matters, such as to study the details of bills that are before Parliament.[119] In addition, if Parliament resolves that NMPs will be appointed during its term, a special select committee on nominations for appointment as NMP is established to consider suggestions for nominees submitted by members of the public.[120]

A standing select committee continues for the duration of a Parliament unless Parliament otherwise provides,[121] while other select committees last until they have presented their final reports.[122] A prorogation of Parliament (see below) does not cause the business and proceedings before select committees to lapse; these are proceeded with in the next session of the same Parliament.[121][122]

| Name | Function | Chairman | Members |

|---|---|---|---|

| Committee of Selection | In charge of selecting MPs to sit on other committees.[123] | Speaker | 7 MPs |

| Committee of Privileges | Looks into complaints of breaches of Parliamentary privilege and any matters that appear to affect the powers and privileges of Parliament (see below).[124] | Speaker | 7 MPs |

| Estimates Committee | Examines the Government's estimates of expenditure, reports what economies consistent with the policy implied in the estimates might be effected, and, subject to the provisions of the law,[125] suggests the form in which the estimates might be presented.[126] | Appointed by Speaker | Not more than 7 MPs |

| House Committee | Considers and advises the Speaker on all matters connected with the comfort and convenience of MPs.[127] | Speaker | 7 MPs |

| Public Accounts Committee | Examines the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and other accounts laid before Parliament as the Committee thinks fit.[128] | Appointed by Speaker | Not more than 7 MPs |

| Public Petitions Committee | Considers all public petitions referred to it and conveys to Parliament all requisite information about their contents.[129] | Speaker | 7 MPs |

| Standing Orders Committee | Considers and reports on all matters relating to the Standing Orders of Parliament referred to it by Parliament.[130] | Speaker | Deputy Speakers and 7 MPs |

Government Parliamentary Committees

Government Parliamentary Committees (GPCs) were established by the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) in 1987. GPCs are Party organs, and were not set up because they are required by any provision of the Constitution or constitutional convention.[131] Each GPC examines the policies, programmes and proposed legislation of a particular government ministry,[131][132] provides the ministry with feedback and suggestions, and is consulted by the ministry on issues of public interest.[133]

The members of GPCs are PAP backbenchers, and each GPC is backed by a resource panel that members of the public are invited to join. When GPCs were introduced, Goh Chok Tong, then First Deputy Prime Minister, said that the three main reasons for establishing GPCs were to increase the participation of MPs in policymaking, to give the public a say in government policies through sitting on resource panels, and to strengthen democratic institutions in the country.[131] It was envisaged that GPC members would act as a sort of proxy opposition in Parliament, challenging the views of Cabinet members. However, in the 1991 general election the PAP lost four seats to opposition parties and suffered a 2.2% drop in popular votes compared to the 1988 election. Goh, who had become Prime Minister in 1990, said in a post-election press conference that GPCs would be abolished as the increased number of Opposition MPs meant they were no longer needed. The PAP would return to the old system of having internal party committees meeting in private. A few weeks later, he said that GPCs would continue to exist, but their members would no longer take an adversarial stance in Parliament.[133]

As of 24 August 2020 there are 12 GPCs dealing with the following matters:[134]

Parliament Secretariat

The administration of Parliament is managed by its secretariat. Among other things, the secretariat organizes the business of Parliament and its committees, managing tasks such as the simultaneous interpretation of debates in the House and the preparation of Hansard (the official reports of Parliamentary debates). The secretariat also assists with the work of the Presidential Council for Minority Rights and the ASEAN Inter-Parliamentary Assembly(AIPA).[135]

The Clerk of Parliament is the chief executive of the secretariat. As of 2009, the clerk is Ms. Ng Sheau Jiuan.[136] She is the principal adviser to the House on parliamentary procedures and practices.[135] When Parliament is sitting, she is stationed at the Clerk's Table below the Speaker's chair, and reads the orders of the day.[137] The clerk is appointed by the president after consultation with the Speaker and the Public Service Commission.[138] She is supported by a deputy clerk, principal assistant clerks and assistant clerks.[135] The independence of the clerk and her staff are protected to some extent by the Constitution. The clerk can only be removed from office on the grounds of inability to discharge the functions of the office (whether arising from an infirmity of body or mind or any other cause) or for misbehaviour, and a parliamentary resolution that has received the affirmative votes of not less than two-thirds of all MPs is required.[139] Further, the staff of Parliament are not eligible for promotion or transfer to any other office in the public service without the Speaker's consent.[140]

Serjeant-at-Arms

The Serjeant-at-Arms is the officer of Parliament who has the duty of maintaining order in the precincts of the House. For instance, if the conduct of any MP is grossly disorderly during a sitting of Parliament, the Speaker or a committee chairman may order him or her to withdraw immediately from Parliament for the rest of the day's sitting, and the Speaker or chairman may instruct the Serjeant to enforce the order.[141] The Speaker may also direct an MP to withdraw when Parliament has voted to suspend him or her for committing the offence of disregarding the authority of the chair or of persistently and wilfully obstructing the business of Parliament. If the MP refuses to obey this direction despite having been summoned several times to do so by the Serjeant acting under the Speaker's orders, the Serjeant may use force to compel the MP's obedience to the direction.[142]

The Serjeant-at-Arms is also the custodian of the Mace of Parliament, and bears the Mace into and out of the chamber of the House – the room where Parliamentary debates take place – during sittings (see below).[143]

Functions

Lawmaking

The legislative power of Singapore is vested in the Legislature of Singapore, which consists of the president and Parliament.[144] One of the Legislature's major functions is lawmaking. As Singapore is an independent and sovereign republic, Parliament has plenary power to pass laws regulating the rights and liabilities of persons in the country and elsewhere.[145] The power of the Legislature to make laws is exercised by Parliament passing bills and the president assenting to them.[146] The president's role in the exercise of legislative power is nominal. He may address Parliament and may send messages to it,[147] and must assent to most bills, which then become law.[148]

A bill is a draft law. In Singapore, most bills are government bills; they are introduced in Parliament by ministers on behalf of the Cabinet. However, any MP can introduce a bill. A bill introduced by an MP who is not a minister is known as a private member's bill. Because the Government currently holds a majority of the seats in Parliament, a private member's bill will not be passed unless it gains the Government's support. Three private members' bills have been introduced since 1965. The first was the Roman Catholic Archbishop Bill, a private bill that was introduced by P. Selvadurai and Chiang Hai Ding in 1974 and passed the following year.[149][150] The first public law that originated from a private member's bill is the Maintenance of Parents Act,[151] which entitles parents at least 60 years old and unable to maintain themselves adequately to apply to a tribunal for their children to be ordered to pay maintenance to them. The bill was introduced on 23 May 1994 by Walter Woon, who was then an NMP, and eventually passed on 2 November 1995.[152] In that year, the first woman NMP, Dr. Kanwaljit Soin, also introduced a Family Violence Bill but it did not pass.[153]

Passage of bills through Parliament

All bills must go through three readings in Parliament and receive the president's assent to become an Act of Parliament. The first reading is a mere formality, during which a bill is introduced without a debate. The bill is considered as having been read after the MP introducing it has read aloud its long title and laid a copy of it on the Table of the House, and the Clerk of Parliament has read out its short title. Copies of the bill are then distributed to MPs, and it is published in the Government Gazette for the public's information. The bill is then scheduled for its second reading.[154]

During the second reading, MPs debate the general principles of the bill. If Parliament opposes the bill, it may vote to reject it.[155] If the bill goes through its second reading, it proceeds to the committee stage where the details of the drafting of the proposed law are examined. Where a bill is relatively uncontroversial, it is referred to a committee of the whole Parliament; in other words, all the MPs present at the sitting form a committee[156] and discuss the bill clause by clause. At this stage, MPs who support the bill in principle but do not agree with certain clauses can propose amendments to those clauses.[157] Bills that are more controversial, or for which it is desired to obtain views from interested groups or the public, are often referred to a select committee.[158] This is a committee made up of MPs who invite interested persons to submit representations on a bill. Public hearings to hear submissions on the bill may also be held. Where the Speaker of Parliament is of the opinion that a bill appears to prejudicially affect individual rights or interests (such a bill is known as a hybrid bill) it must be referred to a select committee, and the committee must hear any affected party who has presented a petition to Parliament.[159] The select committee then reports its findings, together with any suggested amendments to the bill, to Parliament.

Following the committee stage, the bill goes through its third reading. During this stage the principles behind the bill can no longer be questioned, and only minor amendments will be allowed.[160] The bill is then voted upon. In most cases, a simple majority of all the MPs present and voting is all that is needed for the bill to be approved.[161] However, bills seeking to amend the Constitution must be carried by a special majority: not less than two-thirds of all MPs on the second and third readings.[162]

A minister may lay on the Table of the House a certificate of urgency that the president has signed for a proposed bill or a bill that has already been introduced. Once this is done, provided that copies of the bill are provided to MPs, the bill may be proceeded with throughout all its stages until it has been read the third time.[163]

Scrutiny of bills by the Presidential Council for Minority Rights

Most bills passed by Parliament are scrutinized by a non-elected advisory body called the Presidential Council for Minority Rights (PCMR), which reports to the Speaker of Parliament whether there is any clause in a bill that contains a "differentiating measure", that is, one which discriminates against any racial or religious community.[164] When the council makes a favourable report or no report within 30 days of the bill being sent to it (in which case the bill is conclusively presumed not to contain any differentiating measures), the bill is presented to the President for assent.[165]

If the PCMR submits an adverse report, Parliament can either make amendments to the bill and resubmit it to the council for approval, or decide to present the bill for the president's assent nonetheless provided that a Parliamentary motion for such action has been passed by at least two-thirds of all MPs.[166] The PCMR has not rendered any adverse reports since it was set up in 1970.

Three types of bills need not be submitted to the PCMR:[167]

- Money Bills.[168]

- Bills certified by the Prime Minister as affecting the defence or security of Singapore or that relate to public safety, peace, or good order in Singapore.

- Bills that the Prime Minister certifies as so urgent that it is not in the public interest to delay enactment.

Assent to bills by the President

Before a bill officially becomes law, the president must assent to it.[148] The president exercises this constitutional function in accordance with Cabinet's advice and does not act in his personal discretion;[169] thus, except in certain instances described below, he may not refuse to assent to bills that have been validly passed by Parliament. The words of enactment in Singapore statutes are: "Be it enacted by the President with the advice and consent of the Parliament of Singapore, as follows:".[170]

The president may act in his discretion in withholding assent to any of the following types of bills passed by Parliament:[171]

- A bill seeking to amend the Constitution that provides, directly or indirectly, for the circumvention or curtailment of the discretionary powers conferred upon the president by the Constitution.[172]

- A bill not seeking to amend the Constitution that provides, directly or indirectly, for the circumvention or curtailment of the discretionary powers conferred upon the president by the Constitution.[173]

- A bill that provides, directly or indirectly, for varying, changing or increasing the powers of the Central Provident Fund Board to invest the moneys belonging to the Central Provident Fund.[174]

- A bill providing, directly or indirectly, for the borrowing of money, the giving of any guarantee or the raising of any loan by the Government if, in the opinion of the president, the bill is likely to draw on the reserves of the Government which were not accumulated by the Government during its current term of office.[175]

- A Supply Bill, Supplementary Supply Bill or Final Supply Bill (see below) for any financial year if, in the president's opinion, the estimates of revenue and expenditure for that year, the supplementary estimates or the statement of excess, as the case may be, are likely to lead to a drawing on the reserves which were not accumulated by the Government during its current term of office.[176]

As regards a bill mentioned in paragraph 1, the president, acting in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet, may refer to a Constitutional Tribunal the question of whether the bill circumvents or curtails the discretionary powers conferred on him or her by the Constitution. If the Tribunal is of the opinion that the bill does not have this effect, the president is deemed to have assented to the bill on the day after the day when the Tribunal's opinion is pronounced in open court. On the other hand, if the Tribunal feels that the bill does have the circumventing or curtailing effect, and the president either has withheld or withholds his assent to the bill, the Prime Minister may direct that the bill be submitted to the electors for a national referendum. In that case, the bill will only become law if it is supported by not less than two-thirds of the total number of votes cast at the referendum. If 30 days have expired after a bill has been presented to the President for assent and he or she has neither signified the withholding of assent nor referred the Bill to a Constitutional Tribunal, the bill is deemed to have been assented to on the day following the expiry of the 30-day period.[177] The procedure is similar for a bill mentioned in paragraph 2, except that if the Constitutional Tribunal rules that the bill has a circumventing or curtailing effect, the Prime Minister has no power to put the bill to a referendum.[178] This ensures that changes to the president's discretionary powers can only be made by way of constitutional amendments and not ordinary statutes.

If the president withholds his assent to any Supply Bill, Supplementary Supply Bill or Final Supply Bill referred to in paragraph 5 contrary to the recommendation of the Council of Presidential Advisers, Parliament may by resolution passed by not less than two-thirds of the total number of elected MPs overrule the decision of the president.[179] If Parliament does not do so within 30 days of the withholding of assent, it may authorize expenditure or supplementary expenditure, from the Consolidated Fund and Development Fund during the relevant financial year,[180] provided that:[181]

- where the president withholds his assent to a Supply Bill, the expenditure so authorized for any service or purpose for that financial year cannot exceed the total amount appropriated for that service or purpose in the preceding financial year;[182] or

- where the president withholds his assent to a Supplementary Supply Bill or Final Supply Bill, the expenditure so authorized for any service or purpose shall not exceed the amount necessary to replace an amount advanced from any Contingencies Fund under Article 148C(1) of the Constitution for that service or purpose.

If 30 days have passed after a Supply Bill, Supplementary Supply Bill or Final Supply Bill has been presented to the President for assent and her or she has not signified the withholding of assent, the president is deemed to have assented to the bill on the day immediately following the expiration of the 30-day period.[183]

Upon receiving presidential assent, a bill becomes law and is known as an Act of Parliament. However, the Act only comes into force on the date of its publication in the Government Gazette, or on such other date that is stipulated by the Act or another law, or a notification made under a law.[184]

Financial control

All revenues of Singapore that are not allocated to specific purposes by law are paid into a Consolidated Fund.[185] In addition, there exists a Development Fund,[186] which is used for purposes relating to matters such as:[187]

- the construction, improvement, extension, enlargement and replacement of buildings and works and the provision, acquisition, improvement and replacement of other capital assets (including vehicles, vessels, aircraft, rolling-stock, machinery, instruments and equipment) required in respect of or in connection with the economic development or general welfare of Singapore;[188]

- the acquisition of land and the use of any invention;[189]

- the carrying of on any survey, research or investigation before the undertaking of any purpose referred to in paragraph 1, or the formation of any plan or scheme for the development, improvement, conservation or exploitation of the resources of Singapore;[190] and

- capital contributions for investment by way of capital injection in any statutory corporation.[191]

The Government may only withdraw money from the Consolidated Fund and Development Fund if authorized by a Supply law, Supplementary Supply law or Final Supply law passed by Parliament.[192] In this way, Parliament exerts a degree of financial control over the Government as the latter's budget must be approved each year following a debate in the House. However, at present it is virtually certain that the Government's budgets will be approved as it holds a majority of seats in Parliament, and MPs are required by party discipline to vote according to the party line.

The annual budget approval process begins with the Minister for Finance presenting a Budget Statement in Parliament. This usually takes place in late February or early March before the start of the financial year on 1 April. The Budget Statement assesses the performance of Singapore's economy in the previous year and provides information about the Government's financial policy for the coming financial year, including details about tax changes or incentives to be introduced. The Budget Book is presented together with the Budget Statement. This sets out estimates of how each Government ministry proposes to use the public funds allocated to it in the budget in the next financial year.[193][194] Following the Minister's budget speech, Parliament stands adjourned for not less than seven clear days.[195]

When Parliament resumes sitting, two days are allotted for a debate on the Budget Statement,[196] after which Parliament votes on a motion to approve the Government's financial policy as set out in the Statement.[194] Parliament then constitutes itself as the Committee of Supply[197] and debates the estimates of expenditure. During the debates, MPs are entitled to question Ministers on their ministries' policies after giving notice of their intention to move amendments to reduce by token sums of S$100 the total amounts provisionally allocated to particular heads of expenditure.[198] The Committee of Supply debates usually last between seven and ten days,[199] and upon their conclusion a Supply Bill is passed. The enacted law is called a Supply Act.[193]

If the Government wishes to spend public money in addition to what was provided for in the budget, it must submit supplementary estimates to Parliament for approval. If the financial year has not yet ended, such supplementary estimates are passed in the form of a Supplementary Supply Act. As soon as possible after the end of each financial year, the Minister for Finance must introduce into Parliament a Final Supply Bill containing any sums which have not yet been included in any Supply Bill. This is enacted by Parliament as a Final Supply Act.[200][201]

Ministerial accountability

A crucial reason why governmental powers are separated among three branches of government – the Executive, Legislature and Judiciary – is so that the exercise of power by one branch may be checked by the other two branches. In addition to approving the Government's expenditure of public funds, Parliament exercises a check over the Cabinet through the power of MPs to question the Prime Minister and other Ministers regarding the Government's policies and decisions. MPs may put questions to Ministers relating to affairs within their official functions, or bills, motions or other public matters connected with the business of Parliament for which they are responsible. Questions may also be put to other MPs relating to matters that they are responsible for.[202] However, this is a weak check when most of the MPs are members of the political party in power, as they are constrained by party discipline to adhere to the policies it espouses.[203]

Unless a question is urgent and relates to a matter of public importance or to the arrangement of public business and the Speaker's permission has been obtained to ask it, to pose a question an MP must give not later than seven clear days' written notice before the sitting day on which the answer is required.[204] An MP may ask up to five questions at any one time, not more than three of which may be for oral answer.[205] Detailed rules govern the contents of questions. For instance, questions must not contain statements which the MP is not prepared to substantiate;[206] or arguments, inferences, opinions, imputations, epithets or tendentious, ironical or offensive expressions;[207] and a question must not be asked to obtain an expression of opinion, the solution of an abstract legal case or the answer to a hypothetical proposition.[208]

MPs' questions requiring oral answers are raised during Question Time, which is usually one and a half hours from the commencement of each Parliamentary sitting.[209] Written answers are sent to the MP and to the Clerk of Parliament, who circulates the answer to all MPs and arranges for it to be printed in Hansard.[210]

Parliamentary procedure

Parliament regulates and ensure the orderly conduct of its own proceedings and the dispatch of business through the Standing Orders of Parliament, which it is entitled to make, amend and revoke.[211] If there is any matter not provided for by the Standing Orders, or any question relating to the interpretation or application of any Standing Order, the Speaker of Parliament decides how it should be dealt with. He/she may have regard to the practice of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, but is not bound to follow it.[212]

Sessions

Parliament convenes when it is in session. The first session of a particular Parliament commences when Parliament meets after being formed following a general election.[213] Each year there must be at least one session, and not more than six months must intervene between the last sitting of Parliament in any session and the first sitting in the next session.[214] Each Parliament generally has two sessions, although the Seventh Parliament had three sessions: 9 January 1989 to 2 April 1990, 7 June 1990 to 29 January 1991, and 22 February to 14 August 1991.[215] A session usually opens with an address by the president drafted by the Cabinet, which sets out the Government's agenda for the session.[216]

A Parliamentary session concludes in one of two ways. First, the president, on Cabinet's advice, may prorogue Parliament by proclamation in the Government Gazette.[217][218] Prorogation has the effect of suspending the sitting of Parliament, but MPs retain their seats and it is not necessary for an election to be held. Uncompleted Parliamentary business is not affected by a prorogation, and is carried over from one session to the next.[219] For instance, Standing Order 88(1) of the Standing Orders of Parliament states: "A Bill before Parliament shall not lapse upon the prorogation of Parliament and all business and proceedings connected therewith shall be carried over to the next session of the same Parliament and continue from the stage that it had reached in the preceding session." The period between sessions is called a recess.[220]

Secondly, a session terminates when Parliament is dissolved.[221] A dissolution puts an end to a particular Parliament, and all unfinished business is expunged. Dissolution occurs in the following circumstances:

- When five years have elapsed from the date of its first sitting, Parliament is automatically dissolved.[222] The first sitting of the 14th Parliament took place on 24 August 2020,[1] and thus it will be automatically dissolved on 24 August 2025 unless it is dissolved earlier by one of methods stated below.

- If at any time the office of prime minister is vacant, the president may wait a reasonable period to see if there is any other MP likely to command the confidence of a majority of MPs, and who may therefore be appointed prime minister. If there is no such person, the president must dissolve Parliament by proclamation in the Gazette.[223]

- The president may also dissolve Parliament by proclamation if advised by the prime minister to do so, although he/she is not obliged to so act unless he/she is satisfied that the prime minister commands the confidence of a majority of MPs.[224] The president will usually be asked to dissolve Parliament in this manner if the prime minister wishes to call a general election.

The president is not permitted to dissolve Parliament following the giving of a notice of motion in Parliament proposing an inquiry into his conduct unless (1) a resolution is not passed pursuant to the notice of motion; (2) where a resolution has been passed, the tribunal appointed to inquire into the allegations against the president determines that he/she has not become permanently incapable of discharging the functions of his office or that he/she is not guilty of any other allegations; (3) following a tribunal report that is unfavourable to the president, parliament does not successfully pass a resolution for the president's removal from office; or (4) Parliament by resolution requests him/her to dissolve Parliament.[225]

A general election must be held within three months after every dissolution of Parliament.[226] The Prime Minister and other Ministers who make up the Cabinet do not vacate their offices upon a dissolution of Parliament, but continue in their posts until the first sitting of the next Parliament following a general election.[227]

Speaker's procession and the Mace

Unless otherwise notified by the Speaker, a Parliamentary sitting begins at 1:30 pm.[228] It begins with the Speaker's procession, during which the Serjeant-at-Arms enters the chamber of the House bearing the Mace of Parliament on his right shoulder ahead of the Speaker, the Clerk of Parliament, and the Clerk's assistants.[229] Members of Parliament rise in their places upon the entry of the Speaker and bow to him, and he reciprocates. The mace is an ornamented staff that represents the Speaker's authority and is the Serjeant's emblem of office. When Parliament's predecessor, the Legislative Assembly, acquired the Mace in 1958, the Speaker, Sir George Oehlers, invited members to "accept that the Mace is an essential part of the equipment of this Assembly and that this Assembly cannot, in future, be considered to be properly constituted unless the Mace be first brought into the House and laid on the Table".[230] The Mace is placed on the Table of the House, which is a table in the centre of the debating chamber between the front benches.[231] There are two sets of brackets on the Table, and when the Speaker is in his chair the Mace is placed on the upper brackets. The Mace is removed to the lower brackets when the House sits as a committee, and is not brought into the chamber when the president addresses Parliament.[229]

Debates

The quorum for a Parliamentary sitting is one quarter of the total number of MPs, not including the Speaker or someone presiding on his behalf. If any MP contends that there are insufficient MPs attending to form a quorum, the Speaker waits two minutes, then conducts a count of the MPs. If there is still no quorum, he must adjourn Parliament without putting any question.[232]

MPs must occupy the seats in the debating chamber allocated to them by the Speaker.[233] The front benches (those nearest the Table of the House) on the Speaker's right are occupied by Government Ministers, and those on the left by Opposition MPs or by backbenchers.[234] MPs may use any one of the four official languages of Singapore – Malay, English, Mandarin or Tamil – during debates and discussions.[235] Simultaneous oral interpretation of speeches in Malay, Mandarin and Tamil into English and vice versa is provided by the Parliament Secretariat's Language Service Department.[236]

At an ordinary sitting, the order of business in Parliament is as follows:[237]

- Announcements by the Speaker.

- Tributes.

- Obituary speeches.

- Presentation of papers.

- Petitions.

- Questions to Ministers and other MPs.

- Ministerial statements.

- Requests for leave to move the adjournment of Parliament on matters of urgent public importance.

- Personal explanations.

- Introduction of Government Bills.

- Business motions moved by Ministers.

- Motions for leave to bring in bills by private Members.

- Motions, with or without notice, complaining of a breach of privilege or affecting the powers and privileges of Parliament or relating to a report of the Committee of Privileges.

- Public business.

Each debate in Parliament begins with a motion, which is a formal proposal that a certain course of action be taken by the House. The MP who moves a motion has not more than one hour for his or her opening speech explaining the reasons for the motion, but Parliament may vote to extend this time by 15 minutes.[238] The Speaker (or chairman, if Parliament is in committee) then proposes the motion in the form of a question, following which other MPs may debate the motion. MPs who wish to speak must rise in their places and catch the eye of the Speaker. They may speak only if called upon by the Speaker. MPs must speak from the rostrum unless they are front benchers, in which case they may speak at the Table of the House if they wish.[239] Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries may speak for up to one hour, while other MPs may speak for up to 30 minutes (15 minutes if addressing a Committee of the whole Parliament).[240] In general, MPs may only speak once to any question, though they may be heard again to clarify their speeches if misunderstood or to seek a clarification of another MP's speech. If they do so, they are not allowed to introduce new matters.[241] After MPs have spoken, the mover may exercise a right of reply for up to one hour; again, Parliament may grant an extension of up to 15 minutes.[238][242]

During debates, MPs must direct their observations to the Chair of the House occupied by the Speaker or a committee chairman, and not directly to another Member;[243] the phrase "Madam Speaker" or "Mr. Speaker, Sir" is often used for this purpose. Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries are addressed by the offices held by them (for example, "the Honourable Minister for Trade and Industry"), while other MPs are referred to by the constituencies they represent ("the Honourable Member for Holland–Bukit Timah GRC") or by their names.[244] The use of the honorific "the Honourable" is not required by the Standing Orders of Parliament, but during a 1988 parliamentary debate the Leader of the House, Wong Kan Seng, said it would be polite for MPs to refer to their colleagues using the terms "Mr.", "Honourable Mr." or "Honourable Minister" depending on their choice.[245]

MPs must confine their observations to the subject being discussed and may not talk about irrelevant matters, and will be ruled out of order if they use offensive and insulting language about other MPs.[246] They are also not permitted to impute improper motives to other MPs, or to refer to the conduct or character of any MP or public servant other than that person's conduct as an MP or public servant.[247] There are restrictions on discussing the conduct of the president or a Judge or Judicial Commissioner of the Supreme Court;[248] and referring to matters that are sub judice (pending before a court), though when a bill is being considered such cases can be discussed in a way that does not prejudice the parties to the case.[249]

To bring a debate to a close, an MP may move "that the question be now put".[250] The debate ends if the motion is carried (that is, a majority of MPs vote to support the motion). The Speaker then puts the question[251] on the original motion to the House and calls for a vote. To determine whether this motion is carried, the Speaker will "collect the voices" by saying, "As many as are of that opinion say 'Aye'", and MPs supporting the motion will respond "Aye". The Speaker then says "To the contrary say 'No'", and MPs opposing the motion will say "No". Following this, the Speaker assesses the number of votes and says, "I think the Ayes (or Noes) have it".[252] At this point, an MP may challenge the Speaker's decision by claiming a division. If at least five other MPs rise in their places to support the challenge, the Speaker will direct that the division bells be rung for at least a minute. After that, the Speaker orders the Serjeant-at-Arms to lock the doors of the chamber. The Speaker then puts the question a second time. If a division is again claimed, the Speaker asks each MP to vote "Aye" or "No", or to indicate that he or she is abstaining from voting. MPs must vote in the same way as they did when voices were taken collectively. Votes and abstentions are recorded using an electronic system. If it appears that a quorum is not present, the division is invalid and the matter is postponed till the next sitting. Otherwise, the Speaker states the numbers of MPs voting "Aye" and "No" and declares the results of the division. The Serjeant then unlocks the doors.[253]

A Minister may make a statement in Parliament on a matter of public importance. MPs are allowed to seek clarification on the statement but no debate is allowed on it.[254]

Suspension and adjournment

If Parliament decides, a sitting may be suspended at any time after 3:15 pm, and if so suspended resumes at 3:45 pm. The Speaker may also direct that the sitting be suspended at other times. At 7:00 pm the "moment of interruption" is reached. At that point, the proceedings on any business being considered are interrupted and deferred, together with the remaining items of business that have not yet been dealt with, to the next sitting day unless the MPs in charge of the items of business name alternative sitting days for the deferred business to be taken up again.[255] When proceedings have been interrupted or if all items of business have been completed, a Minister must move "That Parliament do now adjourn". Upon that motion, a debate may take place during which any matter that Cabinet is responsible for may be raised by an MP who has obtained the right to raise such a matter for 20 minutes. Each sitting day, only one MP is allotted the right to raise a matter on the motion for the adjournment of Parliament.[256]

An MP can ask for leave to move the adjournment of Parliament for the purpose of discussing a definite matter of urgent public importance. If the MP obtains the general assent of Parliament or at least eight MPs rise in their places to support the motion, the motion stands adjourned until 5:30 pm on the same day. At that time, any proceedings on which Parliament is engaged are suspended so that the urgent matter may be raised. Proceedings on the motion for adjournment may continue until the moment of interruption, whereupon if they have not been completed the motion lapses. The postponed proceedings are resumed either on the disposal or the lapse of the motion for adjournment. Not more than one such motion for adjournment may be made at any one sitting.[257]

Broadcasting of parliamentary proceedings

Key parliamentary proceedings such as the opening of Parliament and the annual budget statement are broadcast live on both free-to-air TV and online. Parliamentary highlights are hosted by Mediacorp's subsidiary CNA through a microsite for six months. Complaints brought by CNA for copyright infringement in relation to a video of parliamentary proceedings hosted on The Online Citizen's Facebook page, resulted in the video being taken down. The Government subsequently clarified that it owns the copyright in such videos.[258]

Privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament

The Constitution provides that the Legislature may by law determine and regulate the privileges, immunities or powers of Parliament.[259] The first such law was enacted in 1962 prior to Singapore's independence by the Legislative Assembly.[260] The current version of that statute is the Parliament (Privileges, Immunities and Powers) Act.[261]