American marten

The American pine marten[1] (Martes americana), also known as the American marten, is a species of North American mammal, a member of the family Mustelidae. The species is sometimes referred to as simply the pine marten. The name "pine marten" is derived from the common name of the distinct Eurasian species Martes martes. The American marten differs from the fisher (Pekania pennanti) in that it is smaller in size and lighter in color.

| American marten | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Martes |

| Species: | M. americana |

| Binomial name | |

| Martes americana | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| |

| |

| American marten range (note: map is missing distribution in New England and New York State) | |

Taxonomy

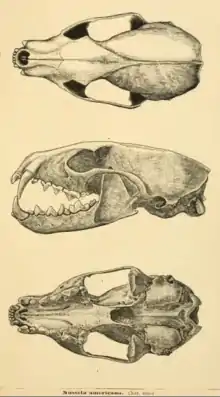

14 subspecies have been recognized. Two subspecies groups have been recognized based on fossil history, cranial analysis, and mitochondrial DNA analysis.[4] None of the subspecies are separable based on morphology and subspecies taxonomy is usually ignored except with regards to conservation issues centered around subspecies rather than ranges.[5] The Martes americana caurina subspecies group is increasingly being considered as its own species, the Pacific marten (Martes caurina)[6][7].

Martes americana americana subspecies group:

- M. a. abieticola (Preble)

- M. a. abietinoides (Gray)

- M. a. actuosa (Osgood)

- M. a. americana (Turton)

- M. a. atrata (Bangs)

- M. a. brumalis (Bangs)

- M. a. kenaiensis (Elliot)

Martes americana caurina subspecies group:

- M. a. caurina (Merriam)

- M. a. humboldtensis (Grinnell and Dixon)

- M. a. nesophila (Osgood)

- M. a. origenes (Rhoads)

- M. a. sierrae (Grinnell and Storer)

- M. a. vancouverensis (Grinnell and Dixon)

- M. a. vulpina (Rafinesque)

Distribution and habitat

The American marten is broadly distributed in northern North America. From north to south its range extends from the northern limit of treeline in arctic Alaska and Canada to northern New Mexico. From east to west its distribution extends from Newfoundland and south west to Humboldt County, California. In Canada and Alaska, American marten distribution is vast and continuous. In the western United States, American marten distribution is limited to mountain ranges that provide preferred habitat. Over time, the distribution of American marten has contracted and expanded regionally, with local extirpations and successful recolonizations occurring in the Great Lakes region and some parts of the Northeast.[8] The American marten has been reintroduced in several areas where extinction occurred.[9]

Martens were once thought to live only in old conifer (evergreen) forests but further study shows that martens live in both old and young deciduous (leafy) and conifer forests[10] as well as mixed forests, including in Alaska and Canada, the Pacific Northwest of the United States[11] and south into northern New England[12][13][14]and the Adirondacks in New York[15] and through the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada. Groups of martens also live in the Midwest in Wisconsin and much of Minnesota.[10] Trapping and destruction of forest habitat have reduced its numbers, but it is still much more abundant than the larger fisher. The Newfoundland subspecies of this animal (Martes americana atrata) is considered to be threatened. The Pacific Northwest subspecies, the Humboldt marten, is even more so, with only a few hundred individuals remaining.[16]

Home range

Compared to other carnivores, American marten population density is low for their body size. One review reports population densities ranging from 0.4 to 2.5 individuals/km2.[8] Population density may vary annually[17] or seasonally.[18] Low population densities have been associated with low abundance of prey species.[8]

Home range size of the American marten is extremely variable, with differences attributable to sex,[19][20][21][22] year, geographic area,[8] prey availability,[8][23] cover type, quality or availability,[8][23] habitat fragmentation,[24] reproductive status, resident status, predation,[25] and population density.[23] Home range size does not appear to be related to body size for either sex.[19] Home range size ranged from 0.04 sq mi (0.1 km2) in Maine to 6.1 sq mi (15.7 km2) in Minnesota for males, and 0.04 sq mi (0.1 km2) in Maine to 3.0 sq mi (7.7 km2) in Wisconsin for females.[23]

Males generally exhibit larger home ranges than females,[19][20][21][22] which some authors suggest is due to more specific habitat requirements of females (e.g., denning or prey requirements) that limit their ability to shift home range.[20] However, unusually large home ranges were observed for 4 females in two studies (Alaska[26] and Quebec[17]). Males and females in northeastern California appeared to have approximately equal home range size.[27]

Home ranges are indicated by scent-marking. American marten male pelts often show signs of scarring on the head and shoulders, suggesting intrasexual aggression that may be related to home range maintenance.[23] Home range overlap is generally minimal or nonexistent between adult males[18][21][28] but may occur between males and females,[18][21] adult males and juveniles,[21][29] and between females.[30]

Several authors have reported that home range boundaries appear to coincide with topographical or geographical features. In northeastern California, movements and home range boundaries were influenced by cover, topography (forest-meadow edges, open ridgetop, lakeshores), and other American marten.[27] In south-central Alaska, home range boundaries included creeks and a major river.[21] In an area burned 8 years previously in interior Alaska, home range boundaries coincided with transition areas between riparian and nonriparian habitats.[30] In northwestern Montana, home range boundaries appeared to coincide with the edge of large open meadows and burned areas; the authors suggested that open areas represent a "psychological rather than physical barriers".[31]

Description

The American marten is a long, slender-bodied weasel about the size of a mink with relatively large rounded ears, short limbs, and a bushy tail. American marten have a roughly triangular head and sharp nose. Their long, silky fur ranges in color from pale yellowish buff to tawny brown to almost black. Their head is usually lighter than the rest of their body, while the tail and legs are darker. American marten usually have a characteristic throat and chest bib ranging in color from pale straw to vivid orange.[9] Sexual dimorphism is pronounced, with males averaging about 15% larger than females in length and as much as 65% larger in body weight.[9]

Total length ranges from 1.5 to 2.2 feet (0.5–0.7 m),[32][8] with tail length of 5.4 to 6.4 inches (135–160 mm),[32] Adult weight ranges from 1.1 to 3.1 pounds (0.5–1.4 kg)[32][8] and varies by age and location. Other than size, sexes are similar in appearance.[8] American marten have limited body-fat reserves, experience high mass-specific heat loss, and have a limited fasting endurance. In winter, individuals may go into shallow torpor daily to reduce heat loss.[33]

Behavior

American marten activity patterns vary by region,[23] though in general, activity is greater in summer than in winter.[9][33] American marten may be active as much as 60% of the day in summer but as little as 16% of the day in winter[33] In north-central Ontario individuals were active about 10 to 16 hours a day in all seasons except late winter, when activity was reduced to about 5 hours a day. In south-central Alaska, American marten were more active in autumn (66% active) than in late winter and early spring (43% active).[21] In northeastern California, more time was spent traveling and hunting in summer than in winter, suggesting that reduced winter activity may be related to thermal and food stress or may be the result of larger prey consumption and consequent decrease in time spent foraging.[34]

American marten may be nocturnal or diurnal. Variability in daily activity patterns has been linked to activity of major prey species,[23][34] foraging efficiency,[21] gender, reducing exposure to extreme temperatures,[21][23][30] season,[28][33][34] and timber harvest. In northeastern California, activity in the snow-free season (May–December) was diurnal, while winter activity was largely nocturnal.[34] In south-central Alaska, American marten were nocturnal in autumn, with strong individual variability in diel activity in late winter. Activity occurred throughout the day in late winter and early spring.[21]

Daily distance traveled may vary by age,[26] gender, habitat quality, season,[28] prey availability, traveling conditions, weather, and physiological condition of the individual. Year-round daily movements in Grand Teton National Park ranged from 0 to 2.83 miles (0–4.57 km), averaging 0.6-mile (0.9 km, observations of 88 individuals).[28] One marten in south-central Alaska repeatedly traveled 7 to 9 miles (11–14 km) overnight to move between 2 areas of home range focal activity.[21] One individual in central Idaho moved as much as 9 miles (14 km) a day in winter, but movements were largely confined to a 1,280-acre (518 ha) area. Juvenile American marten in east-central Alaska traveled significantly farther each day than adults (1.4 miles (2.2 km) vs. 0.9-mile (1.4 km)).[26]

Weather factors

Weather may impact American marten activity, resting site use, and prey availability. Individuals may become inactive during storms or extreme cold.[23][35] In interior Alaska, a decrease in above-the-snow activity occurred when ambient temperatures fell below −4 °F (−20 °C).[30] In southeastern Wyoming, temperature influenced resting site location. Above-snow sites were used during the warmest weather, while subnivean sites were used during the coldest weather, particularly when temperatures were low and winds were high following storms. High mortality may occur if American marten become wet in cold weather, as when unusual winter rains occur during live trapping.[9] In Yosemite National Park, drought conditions increased the diversity of prey items; American marten consumed fish and small mammal species made more accessible by low snow conditions in a drought year.[35]

A snowy habitat in many parts of the range of the American marten provides thermal protection[29] and opportunities for foraging and resting.[28] American marten may travel extensively under the snowpack. Subnivean travel routes of >98 feet (30 m) were documented in northeastern Oregon,[36] >33 feet (10 m) on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan,[36] and up to 66 feet (20 m) in Wyoming.[28]

American marten are well adapted to snow. On the Kenai Peninsula, individuals navigated through deep snow regardless of depth, with tracks rarely sinking >2 inches (5 cm) into the snow pack. Snowfall pattern may affect distribution, with the presence of American marten linked to deep snow areas.[29]

Adaptations to deep snow are particularly important in areas where the American marten is sympatric with the fisher, which may compete with and/or prey on American marten. In California, American marten were closely associated with areas of deep snow (>9 inches (23 cm)/winter month), while fishers were more associated with shallow snow (<5 inches (13 cm)/winter month). Overlap zones were areas with intermediate snow levels. Age and recruitment ratios suggested that there were few reproductive American marten where snow was shallow and few reproductive fishers where snow was deep.[37]

Where deep snow accumulates, American marten prefer cover types that prevent snow from packing hard and have structures near the ground that provide access to sub nivean sites.[38] While American marten select habitats with deep snow, they may concentrate activity in patches with relatively shallow snow. In north-central Idaho, American marten activity was highest in areas where snow depths were <12 inches (30 cm). This was attributed to easier burrowing for food and more shrub and log cover.[39]

Reproduction

Breeding

American marten reach sexual maturity by 1 year of age, but effective breeding may not occur before 2 years of age.[33] In captivity, 15-year-old females bred successfully.[9][40] In the wild, 12-year-old females were reproductive.[40]

Adult American marten are generally solitary except during the breeding season.[9] They are polygamous, and females may have multiple periods of heat.[40] Females enter estrus in July or August,[33] with courtship lasting about 15 days.[9] Embryonic implantation is delayed until late winter, with active gestation lasting approximately two months.[10] Females give birth in late March or April to a litter ranging from 1 to 5 kits.[33] Annual reproductive output is low according to predictions based on body size. Fecundity varies by age and year and may be related to food abundance.[8]

Denning behavior

Females use dens to give birth and to shelter kits. Dens are classified as either natal dens, where parturition takes place, or maternal dens, where females move their kits after birth.[8] American marten females use a variety of structures for natal and maternal denning, including the branches, cavities or broken tops of live trees, snags,[28] stumps, logs,[28] woody debris piles, rock piles, and red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) nests or middens. Females prepare a natal den by lining a cavity with grass, moss, and leaves.[23] They frequently move kits to new maternal dens once kits are 7–13 weeks old. Most females spend more than 50% of their time attending dens in both pre-weaning and weaning periods, with less time spent at dens as kits aged. Paternal care has not been documented.[8]

Development of young

Weaning occurs at 42 days. Young emerge from dens at about 50 days but may be moved by their mother before this.[8] In northwestern Maine, kits were active but poorly coordinated at 7 to 8 weeks, gaining coordination by 12 to 15 weeks. Young reach adult body weight around 3 months.[33]

Kits generally stay in the company of their mother through the end of their first summer, and most disperse in the fall.[8] The timing of juvenile dispersal is not consistent throughout American marten's distribution, ranging from early August to October.[8] In south-central Yukon, young-of-the-year dispersed from mid-July to mid-September, coinciding with the onset of female estrus.[18] Observations from Oregon[25] and Yukon[18] suggest that juveniles may disperse in early spring. Of 9 juvenile American marten that dispersed in spring in northeastern Oregon, 3 dispersed a mean of 20.7 miles (33.3 km) (range: 17.4–26.8 miles (28.0–43.2 km)) and established home ranges outside of the study area. Three were killed after dispersing distances ranging from 5.3 to 14.6 miles (8.6–23.6 km), and 3 dispersed a mean of 5.0 miles (8.1 km) (range: 3.7–6.0 miles (6.0–9.6 km)) but returned and established home ranges in the area of their original capture. Spring dispersal ended between June and early August, after which individuals remained in the same area and established a home range.[25]

Food habits

American marten are opportunistic predators, influenced by local and seasonal abundance and availability of potential prey.[33] They require about 80 cal/day while at rest, the equivalent of about 3 voles (Microtus, Myodes, and Phenacomys spp.).[23] Voles dominate diets throughout the American marten's geographic range,[33] though larger prey—particularly snowshoe hares—may be important, particularly in winter.[29] Red-backed voles (Myodes spp.) are generally taken in proportion to their availability, while meadow voles (Microtus' spp.) are taken in excess of their availability in most areas. Deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) and shrews (Soricidae) are generally eaten less than expected, but may be important food items in areas lacking alternative prey species.[8] Birds were the most important prey item in terms of frequency and volume on the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. Fish may be important in coastal areas.[41]

American marten diet may shift seasonally[21][27][29][34][39] or annually.[21][35] In general, diet is more diverse in summer than winter, with summer diets containing more fruit, other vegetation, and insects. Diet is generally more diverse in the eastern and southern parts of American marten's distribution compared to the western part,[33] though there is high diversity in the Pacific states. American marten exhibit the least diet diversity in the subarctic, though diversity may also be low in areas where the diet is dominated by large prey species (e.g., snowshoe hares or red squirrels).[42]

American marten may be important seed dispersers; seeds generally pass through the animal intact, and seeds are likely germinable. One study from Chichagof Island, southeast Alaska, found that Alaska blueberry (Vaccinium alaskensis) and ovalleaf huckleberry (V. ovalifolium) seeds had higher germination rates after passing through the gut of American marten compared to seeds that dropped from the parent plant. Analyses of American marten movement and seed passage rates suggested that American marten could disperse seeds long distances: 54% of the distances analyzed were >0.3-mile (0.5 km).[43]

Mortality

Life span

American marten in captivity may live for 15 years. The oldest individual documented in the wild was 14.5 years old. Survival rates vary by geographic region, exposure to trapping, habitat quality, and age. In an unharvested population in northeastern Oregon, the probability of survival of American marten ≥9 months old was 0.55 for 1 year, 0.37 for 2 years, 0.22 for 3 years, and 0.15 for 4 years. The mean annual probability of survival was 0.63 for 4 years.[44] In a harvested population in east-central Alaska, annual adult survival rates ranged from 0.51 to 0.83 over 3 years of study. Juvenile survival rates were lower, ranging from 0.26 to 0.50.[26] In Newfoundland, annual adult survival was 0.83. Survival of juveniles from October to April was 0.76 in a protected population, but 0.51 in areas open to snaring and trapping.[24] In western Quebec, natural mortality rates were higher in clearcut areas than in unlogged areas.[45]

Predators

American marten are vulnerable to predation from raptors and other carnivores. The threat of predation may be an important factor shaping American marten habitat preferences, a hypothesis inferred from their avoidance of open areas and from behavioral observations of the European pine marten (Martes martes).[8] Specific predators vary by geographic region. In Newfoundland, red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) were the most frequent predator, though coyote (Canis latrans) and other American marten were also responsible for some deaths.[24] In deciduous forests in northeastern British Columbia, most predation was attributed to raptors.[22] Of 18 American marten killed by predators in northeastern Oregon, 8 were killed by bobcats (Lynx rufus), 4 by raptors, 4 by other American marten, and 2 by coyotes. Throughout the distribution of American marten, other predators include the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), Canada lynx (L. canadensis), mountain lion (Puma concolor),[9][40] fisher (M. pennanti), wolverine (Gulo gulo), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis), American black bear (U. americanus), and grey wolf (C. lupus).[30] In northeastern Oregon, most predation (67%) occurred between May and August, and no predation occurred between December and February.[44]

Hunting

The fur of the American marten is shiny and luxuriant, resembling that of the closely related sable. At the turn of the twentieth century, the American marten population was depleted due to the fur trade. The Hudson's Bay Company traded in pelts from this species among others. Numerous protection measures and reintroduction efforts have allowed the population to increase, but deforestation is still a problem for the marten in much of its habitat. American marten are trapped for their fur in all but a few states and provinces where they occur.[33] The highest annual take in North America was 272,000 animals in 1820.[23]

Trapping is a major source of American marten mortality in some populations[26][45] and may account for up to 90% of all deaths in some areas.[8] Overharvesting has contributed to local extirpations.[46] Trapping may impact population density, sex ratios and age structure.[8][23][33] Juveniles are more vulnerable to trapping than adults,[24][46] and males are more vulnerable than females.[8][24] American marten are particularly vulnerable to trapping mortality in industrial forests.[33]

Other

Other sources of mortality include drowning,[36] starvation,[47] exposure,[44] choking, and infections associated with injury.[24] During live trapping, high mortality may occur if individuals become wet in cold weather.[9]

American marten host several internal and external parasites, including helminths, fleas (Siphonaptera), and ticks (Ixodida).[23] American marten in central Ontario carried both toxoplasmosis and Aleutian disease, but neither affliction was suspected to cause significant mortality.[40] High American marten mortality in Newfoundland was caused by encephalitis.[47]

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document: "Martes americana".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document: "Martes americana".

- Helgen, K. & Reid, F. (2016). Martes americana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41648A45212861.en

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). "Martes americana". Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Martes americana, MSW3

- Stone, Katharine. (2010). "Martes americana, American marten". In: Fire Effects Information System. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Retrieved on 2018-11-11.

- Chapman, Joseph A.; Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce C. (2003). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. p. 635. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5

- https://www.fws.gov/arcata/es/mammals/HumboldtMarten/documents/2018%2012%20Month%20Finding/20180709_Coastal_Marten_SSA_v2.0.pdf

- https://bioone.org/journals/northwest-science/volume-93/issue-2/046.093.0204/Status-of-Pacific-Martens-Martes-caurina-on-the-Olympic-Peninsula/10.3955/046.093.0204.full

- Buskirk, Steven W.; Ruggiero, Leonard F. (1994). "American marten}, pp. 7–37 in Ruggiero, Leonard F.; Aubry, Keith B.; Buskirk, Steven W.; Lyon, L. Jack; Zielinski, William J., tech. eds. The scientific basis for conserving carnivores: American marten, fisher, lynx, and wolverine. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-254. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

- Clark, Tim W.; Anderson, Elaine; Douglas, Carman; Strickland, Marjorie (1987). "Martes americana" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 289 (289): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3503918. JSTOR 3503918. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- "American marten". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Larrison, Patrick and Larrison, Earl J. (1976). Mammals of the Northwest ISBN 0-914516-04-3

- List of Vermont's Wild Mammals Archived 20 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF) Retrieved on 2011-05-28.

- List of Wild Mammals in Maine. Maine Dept of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Retrieved on 2011-05-28.

- List of New Hampshire Wildlife Archived 3 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Wildlife.state.nh.us. Retrieved on 2011-05-28.

- https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/45531.html

- "Protections urged for Humboldt Martens". Curry Coastal Pilot. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Godbout, Guillaume; Ouellet, Jean-Pierre (2008). "Habitat selection of American marten in a logged landscape at the southern fringe of the boreal forest" (PDF). Ecoscience. 15 (3): 332–342. doi:10.2980/15-3-3091. S2CID 56313524.

- Archibald, W. R.; Jessup, R. H. (1984). "Population dynamics of the pine marten (Martes americana) in the Yukon Territory", pp. 81–97 in Olson, Rod; Hastings, Ross; Geddes, Frank, eds. Northern ecology and resource management: Memorial essays honouring Don Gill. Edmonton, Alberta: The University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0888640471.

- Smith, Adam C; Schaefer, James A (2002). "Home-range size and habitat selection by American marten (Martes americana) in Labrador". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 80 (9): 1602–1609. doi:10.1139/z02-166.

- Phillips, David M.; Harrison, Daniel J.; Payer, David C (1998). "Seasonal changes in home-range area and fidelity of martens". Journal of Mammalogy. 79 (1): 180–190. doi:10.2307/1382853. JSTOR 1382853.

- Buskirk, Steven William. (1983). The ecology of marten in southcentral Alaska. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska. Dissertation

- Poole, Kim G.; Porter, Aswea D.; Vries, Andrew de; Maundrell, Chris; Grindal, Scott D.; St. Clair, Colleen Cassady (2004). "Suitability of a young deciduous-dominated forest for American marten and the effects of forest removal". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (3): 423–435. doi:10.1139/z04-006.

- Strickland, Marjorie A.; Douglas, Carman W. (1987), "Marten", pp. 531–546 in Novak, Milan; Baker, James A.; Obbard, Martyn E.; Malloch, Bruce, eds. Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. North Bay, ON: Ontario Trappers Association. ISBN 0774393653.

- Hearn, Brian J. (2007). Factors affecting habitat selection and population characteristics of American marten (Martes americana atrata) in Newfoundland. Orono, ME: The University of Maine. PhD Thesis.

- Bull, Evelyn L.; Heater, Thad W (2001). "Home range and dispersal of the American marten in northeastern Oregon". Northwestern Naturalist. 82 (1): 7–11. doi:10.2307/3536641. JSTOR 3536641.

- Shults, Bradley Scott. (2001). Abundance and ecology of martens (Martes americana) in interior Alaska. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska. Thesis

- Simon, Terri Lee. (1980). An ecological study of the marten in the Tahoe National Forest, California. Sacramento, CA: California State University. Thesis

- Hauptman, Tedd N. (1979). Spatial and temporal distribution and feeding ecology of the pine marten. Pocatello, ID: Idaho State University. Thesis

- Schumacher, Thomas V.; Bailey, Theodore N.; Portner, Mary F.; Bangs, Edward E.; Larned, William W. (1989). Marten ecology and distribution on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska. Draft manuscript. Soldotna, AK: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Lab, Missoula, MT; FEIS files

- Vernam, Donald J. (1987). Marten habitat use in the Bear Creek burn, Alaska. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska. MsC Thesis

- Hawley, Vernon D.; Newby, Fletcher E (1957). "Marten home ranges and population fluctuations". Journal of Mammalogy. 38 (2): 174–184. doi:10.2307/1376307. JSTOR 1376307.

- Martes americana (American Marten). Idaho State University

- Powell, Roger A.; Buskirk, Steven W.; Zielinski, William J. (2003). "Fisher and marten: Martes pennanti and Martes americana", pp. 635–649 in Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, Bruce C.; Chapman, Joseph A., eds. Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, and conservation. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7416-1

- Zielinski, William J.; Spencer, Wayne D.; Barrett, Reginald H (1983). "Relationship between food habits and activity patterns of pine martens". Journal of Mammalogy. 64 (3): 387–396. doi:10.2307/1380351. JSTOR 1380351.

- Hargis, Christina Devin. (1981). Winter habitat utilization and food habits of the pine marten (Martes americana) in Yosemite National Park. Berkeley, CA: University of California. Thesis

- Thomasma, Linda Ebel. (1996). Winter habitat selection and interspecific interactions of American martens (Martes americana) and fishers (Martes pennanti) in the McCormick Wilderness and surrounding area. Houghton, MI: Michigan Technological University. Dissertation

- Krohn, W B; Elowe, K D; Boone, R B (1995). "Relations among fishers, snow, and martens: development and evaluation of two hypotheses". Forestry Chronicle. 71 (1): 97–105. doi:10.5558/tfc71097-1.

- Buskirk, Steven W.; Powell, Roger A. "Habitat ecology of fishers and American martens". in Buskirk, pp. 283–296

- Koehler, Gary M.; Hornocker, Maurice G (1977). "Fire effects on marten habitat in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness". Journal of Wildlife Management. 41 (3): 500–505. doi:10.2307/3800522. JSTOR 3800522.

- Strickland, Marjorie A.; Douglas, Carman W.; Novak, Milan; Hunziger, Nadine P. (1982). "Marten: Martes americana". In: Chapman, Joseph A.; Feldhamer, George A., eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 599–612. ISBN 0-8018-2353-6

- Nagorsen, David W.; Campbell, R. Wayne; Giannico, Guillermo R. (1991). "Winter food habits of marten, Martes americana, on the Queen Charlotte Islands". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 105 (1): 55–59.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Martin, Sandra K. (1994). "Feeding ecology of American martens and fishers", in Buskirk, pp. 297–315

- Hickey, Jena R. (1997). The dispersal of seeds of understory shrubs by American martens, Martes americana, on Chichagof Island, Alaska. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming. Thesis

- Bull, Evelyn L.; Heater, Thad W (2001). "Survival, causes of mortality, and reproduction in the American marten in northeastern Oregon" (PDF). Northwestern Naturalist. 82 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3536640. JSTOR 3536640.

- Potvin, Francois; Breton, Laurier. (1995). "Short-term effects of clearcutting on martens and their prey in the boreal forest of western Quebec", pp. 452–474 in Proulx, Gilbert; Bryant, Harold N.; Woodard, Paul M., eds. Martes: taxonomy, ecology, techniques, and management: Proceedings of the 2nd international Martes symposium; 1995 August 12–16; Edmonton, AB. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Press

- Berg, William E.; Kuehn, David W. "Demography and range of fishers and American martens in a changing Minnesota landscape", in Buskirk, pp. 262–271

- Fredrickson, Richard John. (1990). The effects of disease, prey fluctuation, and clear cutting on American marten in Newfoundland. Logan, UT: Utah State University. Thesis.

Bibliography

- Buskirk, Steven W.; Harestad, Alton S.; Raphael, Martin G.; Powell, Roger A., eds. (1994). Martens, sables, and fishers: Biology and conservation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2894-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martes americana. |