Hooded seal

The hooded seal (Cystophora cristata) is a large phocid found only in the central and western North Atlantic, ranging from Svalbard in the east to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the west. The seals are typically silver-grey or white in color, with black spots that vary in size covering most of the body.[3] Hooded seal pups are known as "blue-backs" because their coats are blue-grey on the back with whitish bellies, though this coat is shed after 14 months of age when the pups molt.[4]

| Hooded seal[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen at Museum Koenig | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipediformes |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Subfamily: | Phocinae |

| Genus: | Cystophora Nilsson, 1820 |

| Species: | C. cristata |

| Binomial name | |

| Cystophora cristata (Erxleben, 1777) | |

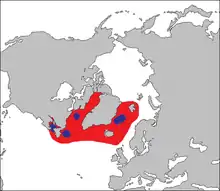

| |

| Distribution of the hooded seal. Breeding grounds indicated in blue. | |

Naming

The generic name Cystophora means "bladder-bearer" in Greek, from the species' unusual sexual ornament – a peculiar inflatable bladder septum on the head of the adult male. This bladder hangs between the eyes and down over the upper lip in the deflated state. In addition, the hooded seal can inflate a large balloon-like sac from one of its nostrils. This is done by shutting one nostril valve and inflating a membrane, which then protrudes from the other nostril.[5]

Size

Adult males are 2.6 meters (8 ft 6 in) long on average, can grow to 3.5 m, and weigh 300–410 kg (660–900 lb). Sexual dimorphism is obvious from birth and females are much smaller: 2.03 meters (6 ft 8 in) long and weighing 145–300 kg (320–661 lb).[6][7] The Color is silvery; the body is scattered with dark, irregular marks. The head is darker than the rest of the body, and without marks.

Distribution and habitat

Hooded seals live primarily on drifting pack ice and in deep water in the Arctic Ocean and North Atlantic. Although some drift away to warmer regions during the year, their best survival rate is in colder climates. They can be found on four distinct areas with pack ice: near Jan Mayen Island (northeast of Iceland); off Labrador and northeastern Newfoundland; the Gulf of St. Lawrence; and the Davis Strait (off midwestern Greenland).[4][6] Males appear to be localized around areas of complex seabed, such as Baffin Bay, Davis Strait, and the Flemish cap, while females concentrate their habitat efforts primarily on shelf areas, such as the Labrador Shelf.[8] Hooded seals are known to be a highly migratory species that often wander long distances, as far west as Alaska and as far south as the Canary Islands and Guadeloupe.[6] Prior to the mid 1990s, hooded seal sightings in Maine and the east Atlantic were rare, but began increasing in the mid 1990s. From January 1997 to December 1999, a total of 84 recorded sightings of hooded seals occurred in the Gulf of Maine, one in France and one in Portugal. From 1996 to 2006, five strandings and sightings were noted near the Spanish coasts in the Mediterranean Sea. There is no scientific explanation for the increase in sightings and range of the hooded seal.[9][10]

Diet

The diet of the hooded seal is composed primarily of various amphipods (crustaceans), euphausiids (krill), and fish, including Atlantic Argentine, capelin, Greenland halibut, cod, herring, and redfish.[4][11] They also are known to eat squid, sea stars, and mussels.[4] Relative to the other species, hooded seals consume 3 times the proportion of redfish; percentages of capelin were similar in relation to closely related species.[11] Capelin is considered a more common choice of sustenance during the winter season. Their diet is considered to be rich in lipids and fatty acids.[12]

Behavior

Hooded seals tend to feed in relatively deep waters ranging from 100–600 m (330–1,970 ft), and dive from 5 to 25 minute durations. However, some dives can go deeper than 1,016 m (3,333 ft) and as long, or longer, than 52 minutes. Diving is rather continuous, with approximately 90% of their time spent submerged during the day and night, although dives during the day are generally deeper and longer. Dives during the winter are also deeper and longer than those in the summer. It is known that the hooded seal is generally a solitary species, except during breeding and molting seasons. During these two periods, they tend to fast as well. The seals mass annually near the Denmark strait around July, at the time of their molting periods, to mate.[13][14] Hooded seals are a relatively unsocial species compared to other seals, and they are typically more aggressive and territorial. They demonstrate aggression by inflating the "hood" (which is explained in the "Nasal Cavity" section below). They frequently migrate and remain alone for most of the year, except during mating season.[4][6]

Nasal cavity

The hooded seal is known for its uniquely elastic nasal cavity located at the top of its head, also known as the hood.[4] Only males possess this display-worthy nasal sac, which they begin to develop around the age of four.[15] The hood begins to inflate as the seal makes its initial breath prior to going underwater. It then begins to repetitively deflate and inflate as the seal is swimming. The purpose of this happening is for acoustic signaling, meaning that it occurs when the seal feels threatened and attempts to ward off hostile species when competing for resources such as food and shelter.[16] It also serves to communicate their health and superior status to both other males and females they are attempting to attract.[15] In sexually mature males, a pinkish balloon-like nasal membrane comes out of the left nostril to further aid it in attracting a mate. This membrane, when shaken, is able to produce various sounds and calls depending on whether the seal is underwater or on land. Most of these acoustic signals are used in acoustic situation (about 79%), while about 12% of the signals are used for sexual purposes.[17]

Breeding and life cycle

There are four major breeding areas for the hooded seal: the Gulf of St. Lawrence; the "Front" east of Newfoundland; Davis Strait (between Greenland and northern Canada); and the West Ice near Jan Mayen. Male hooded seals are known to have several mates in a single mating season, following the hypothesis that they are polygynous. While some males will defend and mate with just one female for long periods of time, others will be more mobile and tend to mate with multiple females for shorter periods of time, generating maximum offspring within the population.[18] Most males reach sexual maturity by 5 years of age.[19]

Throughout all areas, the hooded seals whelp in late March and early April and molt from June to August.[9] The four recognized herds are generally sorted into two distinct populations: a Northeast (NE) Atlantic population and a Northwest (NW) Atlantic population. It is estimated that 90% of the total NW population give birth on the "Front". The NE herd whelping (giving birth) around Jan Mayen generally disperse into the sea after they breed in March. From April through June, after the breeding season, this species travels long distances to feed and then eventually gather together once again. Although some individuals return to the same area of ice in July to undergo moulting, the majority of the herd molt further North. After molting, the species disperses widely again to feed in the late summer and autumn before returning to the breeding areas again in late winter.[20][21][22]

Offspring

Pups are about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) long at birth and weigh about 24 kilograms (53 lb). They are born on the ice from mid-March to early April with a well-developed blubber layer and having shed their pre-natal coat. They are born with a slate blue-grey coat (giving them the name "blueback"), with a pale cream color on the belly, which they will molt after about 14 months. Nursing of the pup lasts for an average of only 4 days, the shortest lactation period of any mammal, during which the pup doubles in size, gaining around 7 kilograms (15 lb)/day. This is possible because the milk that they drink has a fat content of 60%.[23] The female pup will mature between ages 3 and 6, whereas the male pup will mature between ages 5 and 7.

Early development

Researchers find that due to a pup's differing needs in regards to sustaining work and foraging while under water compared to adults, the skeletal and cardiac muscles develop differently. Studies show that cardiac blood flow provides sufficient O2 to sustain lipolytic pathways during dives, remedying their hypoxic challenge. Cardiac tissue is found to be more developed than skeletal muscles at birth and during the weaning period, although neither tissue is fully developed by the end of the weaning period.[24] Pups are born with fully developed hemoglobin stores (found in blood), but their myoglobin levels (found in skeletal tissue) are only 25–30% of adult levels. These observations conclude that pup muscles are less able to sustain both aerobic ATP and anaerobic ATP production during dives than adults are. This is due to the large stores of oxygen, either bound to hemoglobin or myoglobin, which the seals rely on to dive for extended periods of time.[25] This could be a potential explanation for pups’ short weaning period as diving is essential to their living and survival.[24]

Lifespan

The hooded seal can live to about age 30 to 35.[6]

Threats and conservation practices

Prior to the 1940s, adult hooded seals were primarily hunted for their leather and oil deposits. More recently, the main threats are hunting, including subsistence hunting, and bycatch. Seal strandings are not considered a large threat to Hooded Seal populations but are highly researched. Seal pups are hunted for their blue and black pelts and many mothers are killed in the process, attempting to protect their young. Hunting primarily occurs in areas of Greenland, Canada, Russia, and Norway.[4] Overall, northwest Atlantic Hooded Seal populations are stable or increasing whereas the northeast Atlantic populations have declined by 85–90% within the last 60 years.[2]

It was believed by the scientific community that sonar was leading to mass stranding of Hooded Seals. After multiple sonar tests on captive seals, ranging from 1 to 7 kHz, it became evident that it had little effect on the subjects. The first test on each subject yielded differing results, ranging from reduced diving activity and rapid exploratory swimming. A difference was only noted for all subjects on their initial exposure.[26]

Conservation practices, brought about by international cooperation and the formation of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) led to Hooded Seal population increases. It is now required to hold a license to hunt Hooded Seals in international waters and each license is set a quota. Total allowable catch of hooded seals are set at 10,000 annually.[4]

The Hooded Seal is protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.[27]

Mother with pup.

Mother with pup.

See also

References

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kovacs, K. (2016). "Cystophora cristata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6204A45225150.

- Kovacs, Kit. "Hooded Seal". Noerwegian Polar Institute.

- "Hooded Seal (Cystophora cristata)". National Marine Fisheries Service.

- Hooded Seal (Cystophora cristata), a Weird Animal Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine. Drawfluffy.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-16.

- "Hooded Seals, Cystophora cristata". Marinebio. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Hooded seal images Archived 2011-08-30 at the Wayback Machine. arkive.org

- Andersen, J. M.; Wiersma, Y. F.; Stenson, G. B.; Hammill, M. O.; Rosing-Asvid, A.; Skern-Maurizen, M. (2012). "Habitat selection by hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). ICES Journal of Marine Science (free full text). 70: 173–185. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fss133.

- Harris, D. E.; Lelli, B.; Jakush, G.; Early, G. (2001). "Hooded Seal (Cystophora cristata) Records from the Southern Gulf of Maine". Northeastern Naturalist. 8 (4): 427. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2001)008[0427:HSCCRF]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3858446.

- Bellido, J. J.; Castillo, J. J.; Farfán, M. A.; Martín, J. J.; Mons, J. L.; Real, R. (2009). "First records of hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Mediterranean Sea". Marine Biodiversity Records. 1. doi:10.1017/S1755267207007804.

- Tucker, S.; Bowen, W. D.; Iverson, S. J.; Blanchard, W.; Stenson, G. B. (2009). "Sources of variation in diets of harp and hooded seals estimated from quantitative fatty acid signature analysis (QFASA)". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 384: 287–302. doi:10.3354/meps08000.

- Falk-Petersen, S.; Haug, T.; Hop, H.; Nilssen, K. T.; Wold, A. (2009). "Transfer of lipids from plankton to blubber of harp and hooded seals off East Greenland". Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 56 (21–22): 2080. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.11.020.

- Folkow, L. P.; Blix, A. S. (1999). "Diving behaviour of hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Greenland and Norwegian Seas". Polar Biology. 22: 61–74. doi:10.1007/s003000050391.

- "Cystophora cristata Hooded Seal". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Witmer, Lawrence (2001). "A nose for all reasons". Natural History. 110 (5): 65.

- Frank, RJ.; Ronald, K. (1982). "Some underwater observations of hooded seal, Cystophora cristata (Erxleben), behaviour". Aquatic Mammals. 9 (2): 67–68.

- Ballard, K. A.; Kovacs, K. M. (1995). "The acoustic repertoire of hooded seals (Cystophora cristata)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 73 (7): 1362. doi:10.1139/z95-159.

- Kovacs, K. M. (1990). "Mating strategies in male hooded seals (Cystophora cristata)?". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 68 (12): 2499–2502. doi:10.1139/z90-349.

- Miller, Edward H., Ian L. Jones, and Garry B. Stenson. "Baculum and testes of the hooded seal (Cystophora cristata): growth and size-scaling and their relationships to sexual selection." Canadian Journal of zoology 77.3 (1999): 470-479.

- Andersen, J. M.; Wierma, Y. F.; Stenson, G.; Hammill, M. O.; Rosing-Asvid, A. (2009). "Movement Patterns of Hooded Seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean During the Post-Moult and Pre-Breed Seasons" (PDF). Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science. 42: 1–11. doi:10.2960/j.v42.m649. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- Bowen, W. D.; Myers, R. A.; Hay, K. (1987). "Abundance Estimation of a Dispersed, Dynamic Population: Hooded Seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Northwest Atlantic" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 44 (2): 282. doi:10.1139/f87-037. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- Folkow, L. P.; Mårtensson, P. E.; Blix, A. S. (1996). "Annual distribution of hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) in the Greenland and Norwegian seas". Polar Biology. 16 (3): 179. doi:10.1007/BF02329206.

- Iverson, SJ; Oftedal, OT; Bowen, WD; Boness, DJ; Sampugna, J (1995). "Prenatal and postnatal transfer of fatty acids from mother to pup in the hooded seal". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 165 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1007/bf00264680. PMID 7601954.

- Burns, J. M.; Skomp, N; Bishop, N; Lestyk, K; Hammill, M (2010). "Development of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscles from harp and hooded seals". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (5): 740–8. doi:10.1242/jeb.037929. PMID 20154189.

- Geiseler, Samuel J.; Blix, Arnoldus S.; Burns, Jennifer M.; Folkow, Lars P. (2013). "Rapid postnatal development of myoglobin from large liver iron stores in hooded seals". J Exp Biol. 216 (Pt 10): 1793–8. doi:10.1242/jeb.082099. PMID 23348948.

- Kvadsheim, P. H.; Sevaldsen, E. M.; Folkow, L. P.; Blix, A. S. (2010). "Behavioural and Physiological Responses of Hooded Seals (Cystophora cristata) to 1 to 7 kHz Sonar Signals" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 36 (3): 239. doi:10.1578/AM.36.3.2010.239. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- "Marine Mammal Protection Act". NOAA Fisheries. NOAA. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hooded Seal. |