European pine marten

The European pine marten (Martes martes), also known as the pine marten or the european marten, is a mustelid native to and widespread in Northern Europe. It is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[1] It is less commonly also known as baum marten,[2] or sweet marten.[3]

| European pine marten | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Martes |

| Species: | M. martes |

| Binomial name | |

| Martes martes | |

| |

| European pine marten range (green – native, red – introduced) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Mustela martes Linnaeus, 1758 | |

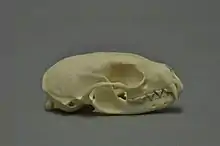

Description

The European pine marten's fur is usually light to dark brown. It is short and coarse in the summer, growing longer and silkier during the winter. It has a cream- to yellow-coloured "bib" marking on its throat. Its body is up to 53 cm (21 in) long, with a bushy tail of about 25 cm (10 in). Males are slightly larger than females; typically, it weighs around 1.5–1.7 kg (3.3–3.7 lb). It has excellent senses of sight, smell, and hearing.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The European pine marten inhabits well-wooded areas.

Great Britain and Ireland

In Great Britain, the species was for many years common only in northwestern Scotland.[5] A study in 2012 found that martens have spread from their Scottish Highlands stronghold, north into Sutherland and Caithness and southeastwards from the Great Glen into Moray, Aberdeenshire, Perthshire, Tayside, and Stirlingshire, with some in the Central Belt, on the Kintyre and Cowal peninsulas and on Skye and Mull. The expansion in the Galloway Forest has been limited compared with that in the core marten range. Martens were reintroduced to the Glen Trool Forest in the early 1980s and only restricted spread has occurred from there.[6] This may be due to ongoing persecution and trapping by local gamekeepers.

In England, pine martens are extremely rare, and long considered probably extinct. A scat found at Kidland Forest in Northumberland in June 2010 may represent either a recolonisation from Scotland, or a relict population that has escaped notice previously.[7] There have been numerous reported sightings of pine martens in Cumbria, however, it was not until 2011 that concrete proof – some scat that was DNA-tested – was found.[8] In July 2015, the first confirmed sighting of a pine marten in England for over a century was recorded by an amateur photographer in woodland in Shropshire.[9] Sightings have continued in this area, and juveniles were recorded in 2019, indicating a breeding population.[10] In July 2017, footage of a live pine marten was captured by a camera trap in the North York Moors in Yorkshire.[11][12] In March 2018 the first ever footage of a pine marten in Northumberland was captured by the Back from the Brink pine marten project.[13]

There is a small population of pine martens in Wales. Scat found in Cwm Rheidol forest in 2007 was confirmed by DNA testing to be from a pine marten. A male was found in 2012 as road kill near Newtown, Powys. This was the first confirmation in Wales of the species, living or dead, since 1971.[14] The Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT) has begun a reinforcement of these mammals in the mid-Wales area. During autumn 2015, 20 pine martens were captured in Scotland, in areas where a healthy pine marten population occurs, under licence from Scottish Natural Heritage. These animals were translocated and released in an area of mid-Wales. All of the martens were fitted with radio collars and are being tracked daily to monitor their movements and find out where they have set up territories. During autumn 2016, the VWT planned to capture and release another 20 pine martens in the hope of creating a self-sustaining population.[15]

The marten is still quite rare in Ireland, but the population is recovering and spreading; its traditional strongholds are in the west and south, especially the Burren and Killarney National Park, but the population in the Midlands has significantly increased in recent years.[16] A study managed by academics at Queens University Belfast, using cameras and citizen scientists, published in 2015, showed that pine martens were distributed across all counties of Northern Ireland.[17]

Behaviour and ecology

Martens are the only mustelids with semiretractable claws. This enables them to lead more arboreal lifestyles, such as climbing or running on tree branches, although they are also relatively quick runners on the ground. They are mainly active at night and dusk. They have small, rounded, highly sensitive ears and sharp teeth adapted for eating small mammals, birds, insects, frogs, and carrion. They have also been known to eat berries, birds' eggs, nuts, and honey. European pine martens are territorial animals that mark their range by depositing feces (called scats) in prominent locations. These scats are black and twisted and can be confused with those of the fox, except that they reputedly have a floral odour.[5] Pine Martens usually make their own dens in hollow trees or scrub-covered fields.

The diet of the pine marten includes small mammals, carrion, birds, insects, and fruits.[18]

The recovery of the European pine marten has been credited with reducing the population of invasive grey squirrels in the UK and Ireland.[19][20] Where the range of the expanding European pine marten population meets that of the grey squirrel, the population of the grey squirrels quickly retreats and the red squirrel population recovers. Because the grey squirrel spends more time on the ground than the red squirrel, which co-evolved with the pine marten, they are thought to be far more likely to come in contact with this predator.[21]

Lifespan

The European pine marten has lived to 18 years in captivity, but in the wild the maximum age attained is only 11 years, with a mere 3–4 years being more typical. They reach sexual maturity at 2–3 years of age. Copulation usually occurs on the ground and can last more than 1 hour.[22] Mating occurs in July and August but the fertilized egg does not enter the uterus for about 7 months. The young are usually born in late March or early April after a 1-month-long gestation period that happens after the implantation of the fertilized egg, in litters of one to five.[4] Young European pine martens weigh around 30 grams at birth. The young begin to emerge from their dens around 7–8 weeks after birth and are able to disperse from the den around 12–16 weeks after their birth.

Threats

Although they are preyed upon occasionally by golden eagles, red foxes, wolves, and wildcats, humans are the largest threat to pine martens. They are vulnerable from conflict with humans, arising from predator control for other species, or following predation of livestock and the use of inhabited buildings for denning. Martens may also be affected by woodland loss.[6] Persecution (illegal poisoning and shooting), loss of habitat leading to fragmentation, and other human disturbances have caused a considerable decline in the pine marten population. They are also prized for their very fine fur in some areas. In the United Kingdom, European pine martens and their dens are offered full protection under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Environmental Protection Act 1990.[23]

References

- Herrero, J.; Kranz, A.; Skumatov, D.; Abramov, A.V.; Maran, T. & Monakhov, V.G. (2016). "Martes martes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T12848A45199169.

- "definition of 'baum marten'". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Definition of 'sweet marten'". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- “Pine Marten (Martes Martes).” Trees for Life, treesforlife.org.uk/forest/pine-marten/.

- "Pine marten". The Vincent Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Scottish Natural Heritage; The Vincent Wildlife Trust (2013). Expansion zone survey of pine marten (Martes martes) distribution in Scotland (Project no: 13645) (PDF) (Commissioned Report). 520. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Found at last! pine marten rediscovered in Northumberland". Northumberland Wildlife Trust. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Pine Marten rediscovered in Cumbria after 10 years!". Wild Travel Magazine. May 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-10-14.

- "Shropshire pine marten sighting is the first in a century". BBC News. 16 July 2015.

- "Shropshire Pine Marten Project". Shropshire Wildlife Trust.

- "Rare pine marten captured on camera in Yorkshire". BBC News. 2017.

- "First ever images of pine marten in Yorkshire". NatureSpy.org. 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- O'Connell, B. (2018). "Rare pine marten captured on camera in Northumberland". Northumberland Gazette. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- McCarthy, M. (2012). "'Extinct' animal turns up in Wales as roadside carcass proves elusive pine martens still exist". The Independent.

- "The pine marten in Wales". The Vincent Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Kelleher, Lynn (4 March 2013). "Red squirrels make comeback as pine martens prey on greys". Irish Independent.

- Macauley, C. (2015). "QUB study shows pine martens are more common in NI than thought". BBC News.

- "Tufty's saviour to the rescue". The Scotsman. 2007.

- Monbiot, G. (2015). "How to eradicate grey squirrels without firing a shot". The Guardian.

- Sheehy, E.; Lawton, C. (2014). "Population crash in an invasive species following the recovery of a native predator: the case of the American grey squirrel and the European pine marten in Ireland". Biodiversity and Conservation. 23 (3): 753–774. doi:10.1007/s10531-014-0632-7.(subscription required)

- "The Pine Marten: FAQs". Pine Marten Recovery Project. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Forder, V. (2006). "Mating behaviour in captive pine martens Martes martes" (PDF). Wildwood Trust. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Pine marten (Martes martes)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2010-03-24. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

External links

- "Pine Marten". Wilderness Classroom.