Abortion law

Abortion laws vary considerably between countries and have changed over time. Such laws range from abortion being freely available on request, to regulation or restrictions of various kinds, to outright prohibition in all circumstances.[1]

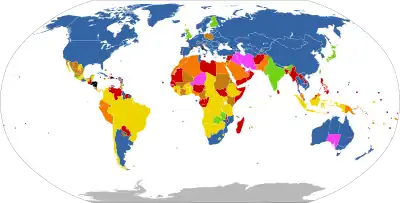

| Legal on request | |

| Legally restricted to cases of: | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape*, fetal impairment*, or socioeconomic factors | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, rape, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life, to her health*, or fetal impairment | |

| Risk to woman's life*, to her health*, or rape | |

| Risk to woman's life or to her health | |

| Risk to woman's life | |

| Illegal with no exceptions | |

| No information | |

| * Does not apply to some countries in that category | |

Abortion continues to be a controversial subject in many societies on religious, moral, ethical, practical, and political grounds. Though it has been banned and otherwise limited by law in many jurisdictions, abortions continue to be common in many areas, even where they are illegal. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), abortion rates are similar in countries where the procedure is legal and in countries where it is not,[2] due to unavailability of modern contraceptives in areas where abortion is illegal.[3]

Also according to the WHO, the number of abortions worldwide is declining due to increased access to contraception.[2] Almost two-thirds of the world's women currently reside in countries where abortion may be obtained on request for a broad range of social, economic, or personal reasons.

History

Abortion has existed since ancient times, with natural abortifacients being found amongst a wide variety of tribal people and in most written sources. The earliest known records of abortion techniques and general reproductive regulation date as far back as 2700 BC in China and 1550 BC in Egypt.[4] Early texts contain no mention of abortion or abortion law. When it does appear, it is entailed in concerns about male property rights, preservation of social order, and the duty to produce fit citizens for the state or community. The harshest penalties were generally reserved for a woman who procured an abortion against her husband's wishes, and for slaves who produced abortion in a woman of high status. Religious texts often contained severe condemnations of abortion, recommending penance but seldom enforcing secular punishment. As a matter of common law in England and the United States, abortion was illegal anytime after quickening—when the movements of the fetus could first be felt by the woman. Under the born alive rule, the fetus was not considered a "reasonable being" in Rerum Natura; and abortion was not treated as murder in English law.

In the 20th century, many Western countries began to codify abortion law or place further restrictions on the practice. Anti-abortion movements, also referred to as Pro-life movements, were led by a combination of groups opposed to abortion on moral grounds, and by medical professionals who were concerned about the danger presented by the procedure and the regular involvement of non-medical personnel in performing abortions. Nevertheless, it became clear that illegal abortions continued to take place in large numbers even where abortions were rigorously restricted. It was difficult to obtain sufficient evidence to prosecute the women and abortion doctors, and judges and juries were often reluctant to convict. For example, Henry Morgentaler, a Canadian pro-choice advocate, was never convicted by a jury. He was acquitted by a jury in the 1973 court case, but the acquittal was overturned by five judges on the Quebec Court of Appeal in 1974. He went to prison, appealed, and was again acquitted. In total, he served 10 months, suffering a heart attack while in solitary confinement. Many were also outraged at the invasion of privacy and the medical problems resulting from abortions taking place illegally in medically dangerous circumstances. Political movements soon coalesced around the legalization of abortion and liberalization of existing laws.

By the mid 20th century, many countries had begun to liberalize abortion laws, at least when performed to protect the life of the woman and in some cases on woman's request. Under Vladimir Lenin, the Soviet Union legalized abortions on request in 1920.[5][6][7][8][9] The Bolsheviks saw abortion as a social evil created by the capitalist system, which left women without the economic means to raise children, forcing them to perform abortions. The Soviet state initially preserved the tsarists ban on abortion, which treated the practice as premeditated murder. However, abortion had been practiced by Russian women for decades and its incidence skyrocketed further as a result of the Russian Civil War, which had left the country economically devastated and made it extremely difficult for many people to have children. The Soviet state recognized that banning abortion would not stop the practice because women would continue using the services of private abortionists. In rural areas, these were often old women who had no medical training, which made their services very dangerous to women's health. In November 1920 the Soviet regime legalized abortion in state hospitals. The state considered abortion as a temporary necessary evil, which would disappear in the future Communist society, which would be able to provide for all the children conceived.[10] In 1936, Joseph Stalin placed prohibitions on abortions, which restricted them to medically recommended cases only, in order to increase population growth after the enormous loss of life in World War I and the Russian Civil War.[11][12][13] In the 1930s, several countries (Poland, Turkey, Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, Mexico) legalized abortion in some special cases (pregnancy from rape, threat to mother's health, fetal malformation). In 1948 abortion was legalized in Japan, 1952 in Yugoslavia (on a limited basis), and 1955 in the Soviet Union (on demand). Some Soviet allies (Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania) legalized abortion in the late 1950s under pressure from the Soviets.[14]

In the United Kingdom, the Abortion Act of 1967 clarified and prescribed abortions as legal up to 28 weeks (later reduced to 24 weeks). Other countries soon followed, including Canada (1969), the United States (1973 in most states, pursuant to Roe v. Wade – the U.S. Supreme Court decision which legalized abortion nationwide), Tunisia (1973), Denmark (1973), Austria (1974), France (1975), Sweden (1975), New Zealand (1977), Italy (1978), the Netherlands (1980), and Belgium (1990). However, these countries vary greatly in the circumstances under which abortion was to be permitted. In 1975, the West German Supreme Court struck down a law legalizing abortion, holding that they contradict the constitution's human rights guarantees. In 1976, a law was adopted which enabled abortions up to 12 weeks. After Germany's reunification, despite the legal status of abortion in former East Germany, a compromise was reached which deemed most abortions up to 12 weeks legal. In jurisdictions governed under sharia law, abortion after the 120th day from conception (19 weeks from LMP) is illegal, especially for those who follow the recommendations of the Hanafi legal school, while most jurists of the Maliki legal school "believe that ensoulment occurs at the moment of conception, and they tend to forbid abortion at any point [similar to the Roman Catholic Church]. The other schools hold intermediate positions. [..] The penalty prescribed for an illegal abortion varies according to particular circumstances involved. According to sharia, it should be limited to a fine that is paid to the father or heirs of the fetus".[15] See also: Islam and abortion.

Timeline of abortion on request

The table below lists in chronological order the UN member states that have legalised abortion on request in at least some initial part of the pregnancy, or that have fully decriminalised abortion.

Notes: Where a country has legalised abortion on request, prohibited it and legalised it again (e.g. former Soviet Union, Romania), only the later year is included. Countries that result from the merger of states where abortion on request was legal at the moment of unification show the year when it became legal across the whole national territory (e.g. Germany, Vietnam). Similarly, countries where not all subnational jurisdictions have legalised abortion on request are not included (e.g. leading to the exclusion of Australia, Mexico and United Kingdom). Countries are counted even if they were not yet independent at the time. The year refers to when the relevant law or judicial decision came into force, which may be different from the year when it was approved.

International law

There are no international or multinational treaties that deal directly with abortion but human rights law and International criminal law touch on the issues.

The Nuremberg Military Tribunal decided the case of United States v Greifelt & others [1948] on the basis that abortion was a crime within its jurisdiction according to the law defining crimes against humanity and thus within its definition of murder and extermination.[23]

The Catholic Church remains highly influential in Latin America, and opposes the legalisation of abortion.[24] The American Convention on Human Rights, which in 2013 had 23 Latin American parties, declares human life as commencing with conception. In Latin America, abortion on request is only legal nationwide in Cuba (1965), Uruguay (2012)[25] and Argentina (2021).[22] It is also legal in Mexico City and in the state of Oaxaca up to the twelfth week of pregnancy (the law on abortion in Mexico varies by state).[26][27] Abortions are completely banned in El Salvador, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic and only allowed in certain restricted circumstances in most other Latin American nations.[24]

In the 2010 case of A, B and C v Ireland, the European Court of Human Rights found that the European Convention on Human Rights did not include a right to an abortion.

In 2005 the United Nations Human Rights Committee ordered Peru to compensate a woman (known as K.L.) for denying her a medically indicated abortion; this was the first time a United Nations Committee had held any country accountable for not ensuring access to safe, legal abortion, and the first time the committee affirmed that abortion is a human right.[28] K.L. received the compensation in 2016.[28] In the 2016 case of Mellet v Ireland, the UN HRC found Ireland's abortion laws violated International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights because Irish law banned abortion in cases of fatal fetal abnormalities.

National laws

While abortions are legal at least under certain conditions in almost all countries, these conditions vary widely. According to a United Nations report with data gathered up to 2019,[29] abortion is allowed in 98% of countries in order to save a woman's life. Other commonly-accepted reasons are preserving physical (72%) or mental health (69%), in cases of rape or incest (61%), and in cases of fetal impairment (61%). Performing an abortion because of economic or social reasons is accepted in 37% of countries. Performing abortion only on the basis of a woman's request is allowed in 34% of countries, including in the United States, Canada, most European countries and China.[29]

The exact scope of each legal ground also varies. For example, the laws of some countries cite health risks and fetal impairment as general grounds for abortion and allow a broad interpretation of such terms in practice, while other countries restrict them to a specific list of medical conditions or subcategories. Many countries also specify different gestational limits for when abortion can be done under each legal ground, for example 12 weeks for abortion on request and no limit to save a woman's life.[29]

In some countries, additional procedures must be followed before the abortion can be carried out even if the basic grounds for it are met. For example, in Finland, where abortions are not granted based merely on a woman's request, approval for each abortion must be obtained from two doctors (or one in special circumstances).[30][31] The vast majority, 90% of abortions in Finland are performed for socio-economic reasons.[32] How strictly all of the procedures dictated in the legislation are followed in practice is another matter. For example, in the United Kingdom, a Care Quality Commission's report in 2012 found that several NHS clinics were circumventing the law, using forms pre-signed by one doctor, thus allowing abortions to patients who only met with one doctor.[33]

Summary tables

| Permitted | |

| Permitted, with complex legality or practice | |

| Varies by subdivision | |

| Prohibited, with complex legality or practice | |

| Prohibited |

Independent countries

The table below summarizes the legal grounds for abortion in all United Nations member states and observer states and some countries with limited recognition. This table is mostly based on data compiled by the United Nations up to 2019,[34] with some updates, additions and clarifications citing other sources.

Autonomous jurisdictions

The table below summarizes the legal grounds for abortion in autonomous jurisdictions not included in the previous table.

Europe

Despite a wide variation in the restrictions under which it is permitted, abortion is legal in most European countries. The exceptions are the mini-state of Malta[134] and the micro-states of Vatican City, San Marino, Liechtenstein and Andorra, where abortion is illegal or severely restricted.[135][136] The other states with existent, but less severe restrictions are Poland and Monaco. All the remaining states make abortion legal on request or for social and economic reasons during the first trimester. When it comes to later-term abortions, there are very few with laws as liberal as those of the United States.[137] Restrictions on abortion are most stringent in a few countries that are strongly observant of the Catholic religion.[135]

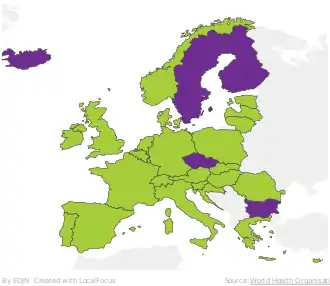

European Union

Most countries in the European Union allow abortion on demand during the first trimester, with Sweden and the Netherlands having more extended time limits.[133] After the first trimester, abortion is generally allowed only under certain circumstances, such as risk to woman's life or health, fetal defects or other specific situations that may be related to the circumstances of the conception or the woman's age. For instance, in Austria, second trimester abortions are allowed only if there is a serious risk to physical health of woman (that cannot be averted by other means); risk to mental health of woman (that cannot be averted by other means); immediate risk to life of woman (that cannot be averted by other means); serious fetal impairment (physical or mental); or if the woman is under 14 years of age. Some countries, such as Denmark, allow abortion after the first trimester for a variety of reasons, including socioeconomic ones, but a woman needs an authorization to have such an abortion.[138] Similarly, in Finland, technically abortions even just up to 12 weeks require authorization from two doctors (unless special circumstances), but in practice the authorization is only a rubber stamp and it is granted if the mother simply does not wish to have a baby.[139]

Access to abortion in much of Europe depends not as much on the letter of the law, but on the prevailing social views which lead to the interpretation of the laws. In much of Europe, laws which allow a second-trimester abortion due to mental health concerns (when it is deemed that the woman's psychological health would suffer from the continuation of the pregnancy) have come to be interpreted very liberally, while in some areas it is difficult to have a legal abortion even in the early stages of pregnancy due to conscientious objection by doctors refusing to perform abortions against their personal moral or religious convictions.[140]

Malta is the only EU country that bans abortion in all cases and does not have an exception for situations where the woman's life is in danger. The law, however, is not strictly enforced in relation to instances where a pregnancy endangers the woman's life.[134]

Abortion in Italy was legalized in 1978.[141] However, the law allows health professionals to refuse to perform an abortion. This conscientious objection has the practical effect of restricting access to abortion.[142]

In Ireland, before December 2018, abortion was illegal except cases where a woman's life was endangered by the continuation of her pregnancy. However, in a 2018 referendum a large majority of Irish citizens voted to repeal the constitutional amendment prohibiting legislation relating to the termination of non-life-threatening pregnancies; and the new law enacted (the Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018) allows abortion on request up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, and in certain circumstances at later stages. Abortion in Northern Ireland was decriminalized on 22 October 2019.[143]

Europe's formerly Communist countries have liberal abortion laws. The only exception is Poland, where abortion is allowed only in cases of risk to the life or health of the woman or when the pregnancy is a result of rape or incest. Abortion in case of fetal defects, which was previously legal, was ruled unconstitutional by the country's Constitutional Tribunal on 22 October 2020.[144] United Nations independent human rights experts criticized the ruling, and called for the Polish authorities to respect the rights of people who were protesting against it.[145] The ruling took effect on 27 January 2021.[74]

Most European countries have laws which stipulate that minor girls need their parents' consent or that the parents must be informed of the abortion. In most of these countries however, this rule can be circumvented if a committee agrees that the girl may be posed at risk if her parents find out about the pregnancy, or that otherwise it is in her best interests to not notify her parents. The interpretation in practice of these laws depends from region to region, as with the other abortion laws.[140] Some countries differentiate between younger pregnant minors and older ones, with the latter not subjected to parental restrictions (for example under or above 16).[146]

In countries where abortion is illegal or restricted, it is common for women to travel to neighboring countries with more liberal laws. It was estimated in 2007 that over 6,000 Irish women travelled to Great Britain to have abortions every year.[140]

United States

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide. It established a minimal period during which abortion must be legal (with more or fewer restrictions throughout the pregnancy). This basic framework, modified in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), is still in effect today. In accordance with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, states cannot place legal restrictions posing an undue burden for "the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus."[147] Although this legal framework established by the Supreme Court is very liberal (particularly with regard to the gestational age), in practice the effective availability of abortion varies significantly from state to state.[148] On June 29, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed abortion rights after striking down a Louisiana law limiting abortion.[149]

Countries with more restrictive laws

According to a report by Women on Waves, approximately 25% of the world's population lives in countries with "highly restrictive abortion laws"—that is, laws which either completely ban abortion, or allow it only to save the mother's life. This category includes several countries in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific region, as well as Malta in Europe.[134][150] The Centre For Reproductive Rights report that 'The inability to access safe and legal abortion care impacts 700 million women of reproductive age' [151]

Latin America is the region with the most restrictive abortion laws. Fewer than 3% of the women in this region live in countries with liberal abortion laws—that is, where abortion is permitted either without restriction as to reason or on socioeconomic grounds.[152] Some of the countries of Central America, notably El Salvador, have also come to international attention due to very forceful enforcement of the laws, including the incarceration of a gang rape victim for homicide when she gave birth to a stillborn son and was accused of attempting an illegal abortion.[153][154][155]

Beginning of pregnancy controversy

Controversy over the beginning of pregnancy occurs in different contexts, particularly in a legal context, and is particularly discussed within the abortion debate from the point of measuring the gestational age of the pregnancy. Pregnancy can be measured from a number of convenient points, including the day of last menstruation, ovulation, fertilization, implantation and chemical detection. A common medical way to calculate gestational age is to measure pregnancy from the first day of the last menstrual cycle.[161] However, not all legal systems use this measure for the purpose of abortion law; for example countries such as Belgium, France, Luxembourg use the term "pregnancy" in the abortion law to refer to the time elapsed from the sexual act that led to conception, which is presumed to be 2 weeks after the end of the last menstrual period.[163]

Exceptions in abortion law

Exceptions in abortion laws occur either in countries where abortion is, as a general rule illegal, or in countries which have abortion on request with gestational limits (for example if a country allows abortion on request until 12 weeks, it may create exceptions to this general gestation limit for later abortions in specific circumstances).[164]

There are a few exceptions commonly found in abortion laws. Legal domains which do not have abortion on demand will often allow it when the health of the mother is at stake. "Health of the mother" may mean something different in different areas: for example, prior to December 2018, the Republic of Ireland allowed abortion only to save the life of the mother, whereas abortion opponents in the United States argue health exceptions are used so broadly as to render a ban essentially meaningless.[165]

Laws allowing abortion in cases of rape or incest often differ. For example, before Roe v. Wade, thirteen US states allowed abortion in the case of either rape or incest, but only Mississippi permitted abortion of pregnancies due to rape, and no state permitted it for just incest.[166]

Many countries allow for abortion only through the first or second trimester, and some may allow abortion in cases of fetal defects, e.g., Down syndrome or where the pregnancy is the result of a sexual crime.

Other related laws

Laws in some countries with liberal abortion laws protect access to abortion services. Such legislation often seeks to guard abortion clinics against obstruction, vandalism, picketing, and other actions, or to protect patients and employees of such facilities from threats and harassment. Other laws create a perimeter around a facility, known variously as a "buffer zone", "bubble zone", or "access zone". This area is intended to limit how close to these facilities demonstration by those who oppose abortion can approach. Protests and other displays are restricted to a certain distance from the building, which varies depending upon the law, or are prohibited altogether. Similar zones have also been created to protect the homes of abortion providers and clinic staff. Bubble zone laws are divided into "fixed" and "floating" categories. Fixed bubble zone laws apply to the static area around the facility itself, and floating laws to objects in transit, such as people or cars.[167] Because of conflicts between anti-abortion activists on one side and women seeking abortion and medical staff who provides abortion on the other side, some laws are quite strict: in South Africa for instance, any person who prevents the lawful termination of a pregnancy or obstructs access to a facility for the termination of a pregnancy faces up to 10 years in prison (section 10.1 (c) of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act[168]).

On 3 November 2020, an association of 20 Kenyan charities urged the government of Kenya to withdraw from the Geneva Consensus Declaration (GCD), a US-led international accord that sought to limit access to abortion for girls and women around the world. GCD was signed by 33 nations, on 22 October 2020.[169]

Case law

Australia

- R v Davidson (Menhennitt ruling) [1969] VicRp 85, [1969] VR 667, Supreme Court (Vic, Australia).

- R v Sood (No 3) [2006] NSWSC 762, Supreme Court (NSW, Australia)

Canada

- Abortion trial of Emily Stowe (1879)

- Azoulay v. The Queen (1952)

- Morgentaler v. The Queen (1976)

- R. v. Morgentaler (1988)

- Borowski v. Canada (Attorney General) (1989)

- Tremblay v. Daigle (1989)

- R. v. Morgentaler (1993)

Germany

Ireland

- Attorney General v. X (1992)

South Africa

United Kingdom

United States

- Roe v. Wade (1973)

- Doe v. Bolton (1973)

- H. L. v. Matheson (1981)

- City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983)

- Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989)

- Hodgson v. Minnesota (1990)

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992)

- Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic (1993)

- Stenberg v. Carhart (2000)

- McCorvey v. Hill (2004)

- Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of New England (2006)

- Gonzales v. Carhart (2007)

- Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt (2016)

European Court of Human Rights

- A. B. and C. v. Ireland (2009)

See also

- Abortion debate

- Abortion-rights movements

- Anti-abortion movement

- Category:Abortion by country

- Conscientious objection to abortion

- Fetal rights

- Hippocratic Oath

- History of abortion

- Legislation on human reproduction

- Medical law

- Mexico City Policy

- Religion and abortion

- Roe v. Wade

- Support for legal abortion

- Abortion in Nigeria

- Ohio "Heartbeat Bill"

- Sherri Finkbine

Notes

- The law legalising abortion on request was approved in 1978 and came into force in 1979.[18]

- The law legalising abortion on request was approved in 2014 and came into force in 2015.[21]

- The law legalising abortion on request was approved in 2020 and came into force in 2021.[22]

- On 25 January 2021, the National Assembly of Thailand approved a law allowing abortion on request in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. The law is expected to take effect on 12 February 2021.[78]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle.

- Under the Penal Code of 1886, abortion is allowed only to save the woman's life as a general legal principle.[36] A new penal code, to take effect on 9 February 2021, allows abortion in cases of risk to life or health of the woman, rape, and fetal impairment.[37]

- Except in Chaco Province, where a judge ordered the suspension of the law legalising abortion on request. The injuction went into effect after the court notified the provincial government on 29 January 2021.[38] The province appealed this decision on 3 February 2021.[39]

- Including external territories.

- Except in South Australia.

- Applies the laws of Western Australia.[41]

- Applies the laws of Western Australia.[42]

- Applies the laws of the Australian Capital Territory.[43]

- Applies the laws of New South Wales.[44]

- The UN source marks it as a legal ground because the Penal Code explicitly prohibits abortion only if performed without the consent of the woman and of a medical practitioner.[45] However, the decree regulating medical practice prohibits abortion unless the pregnancy threatens the woman's life.[46]

- The UN source does not explicitly mark this legal ground for abortion but says that "menstrual regulation is available on request".

- This ground is established by a regulation implementing a judicial decision, although it is not mentioned in the decision itself or in the law.[47]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision only in the case of anencephaly.

- Mainland China.

- A judicial pardon may be granted to the woman for an abortion on this ground.

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle, allowed by regulation and established by treaty.[48][49]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by treaty, whose application is requested by the Constitutional Court.[48][50]

- The UN source says that abortion is permitted for therapeutic purposes but is unclear whether it means only to save the woman's life or also to preserve her health.

- The UN source says that this ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle. However, other sources say that abortion is not legally allowed under any circumstance in the Dominican Republic.[51]

- Abortion is allowed in case of rape of a woman with a mental disability.

- Including the Åland Islands.[52]

- Including Overseas France.[53]

- A new penal code, published by presidential decree in July 2020, would allow abortion on request in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. The code is set to take effect in July 2022 unless modified by the parliament to be elected in September 2021.[54]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law,[56] but it may be included in other legal grounds if the pregnancy causes unbearable hardship, such as significant harm to mental health or risk of suicide.[57]

- The UN source does not explicitly mark it a social legal ground but says that abortion is permitted "if the woman is under marriage age or over the age of 40", or if "the pregnancy is the result of extramarital relations".

- The UN source marks it as a legal ground but it is only established by treaty, not by law and not implemented as of 2020.[58][59]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle and established by judicial decision.[60][61][62][63]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision.[60][61][62][63]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle.[65]

- The UN source marks it as a legal ground but it is only cited in guidelines for health workers, not by law.[66]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle.[67][68]

- Except in Guanajuato and Querétaro.

- In some states and Mexico City.

- Only in Mexico City, Michoacán, Oaxaca and Yucatán.

- Only in Mexico City and Oaxaca.

- Including the Caribbean Netherlands.[70][71]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision in the southern states.

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision.

- Including Svalbard.[73]

- The UN source does not explicitly mark it a social legal ground but says that the ground for risk to health includes "the pregnant woman's actual or reasonably foreseeable environment".

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision.[75][76]

- Only in Northern Ireland.[79]

- In some states, this ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision.

- The law of Vatican City is primarily based on the canon law of the Catholic Church and applies the Italian penal code in force in 1929 with local modifications.[90] Both sources of law prohibit abortion without explicitly mentioning any exception.[91][92] The penal code lists the general principle of necessity to save one's life, which removes punishment for any crime,[92] but the Church's official interpretation of canon 1398 is more restrictive, allowing in such cases only indirect abortion under the principle of double effect.[93][94]

- The UN source does not explicitly mark it a social legal ground but says that abortion is permitted for risk to health of existing children of the woman.

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle.[100]

- Although illegal, the government does not prosecute abortions performed under rules similar to other countries, including on request.[105]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is accepted as a general legal principle.[109]

- Although the law permits abortions on request, few or no medical providers in the territory perform them except to save the woman's life.[97]

- In Alderney and Sark, this ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law.[112] A judicial decision on an identical law in the parent country clarified that the law always implicitly allowed abortion at least to save the woman's life, and the decision allowed it also to preserve her health.[113] It is unclear whether Alderney and Sark apply only the original legal principle or also the judicial decision.

- Except in Alderney and Sark.[112]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law. A judicial decision on an identical law in the parent country clarified that the law always implicitly allowed abortion at least to save the woman's life, and the decision allowed it also to preserve her health.[113] It is unclear whether the territory applies only the original legal principle or also the judicial decision.

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law, but it is included by regulation in the ground for preserving physical or mental health.[114][115]

- The territory's constitution prohibits abortion "except as provided by law", and the territory has no law about the subject. However, according to an opinion issued by the territory's attorney general, U.S. judicial decisions on abortion apply to the territory, thus allowing abortion on request.[120] Yet, in practice, authorized medical providers in the territory perform abortions only to save the woman's life and possibly in case of rape.[121][97]

- Applies English law in force in 2010 unless locally modified.[122]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law but it is established by judicial decision.[124]

- Applies English law in force on 1 January 2006 unless locally modified, in each part of the territory.[125] Tristan da Cunha explicitly applies the abortion law of the United Kingdom with minor modifications.[126]

- Although illegal, the government does not prosecute abortions performed under rules similar to other countries, including on request.[100]

- This ground is not explicitly mentioned in the law. The judicial handbook says that abortion is permitted for medical reasons but is unclear whether it means only to save the woman's life or also to preserve her health.[129]

References

- Population Division, United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2001). Abortion Policies: A Global Review. United Nations Publications. pp. 46, 126. ISBN 978-92-1-151361-5.

- "Abortion Rates Similar In Countries That Legalize, Prohibit Procedure, Study Says". I.C.M.A. Archived from the original on 2014-03-23. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- Singh, Susheela et al. Adding it Up: The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Family Planning and Newborn Health, pages 17, 19, and 27 (New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund 2009): "Some 215 million women in the developing world as a whole have an unmet need for modern contraceptives…. If the 215 million women with unmet need used modern family planning methods....[that] would result in about 22 million fewer unplanned births; 25 million fewer abortions; and seven million fewer miscarriages....If women's contraceptive needs were addressed (and assuming no changes in abortion laws)...the number of unsafe abortions would decline by 73% from 20 million to 5.5 million." A few of the findings in that report were subsequently changed, and are available at: "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine" (Guttmacher Institute 2010).

- Joffe, Carole (2009), "Abortion and Medicine: A Sociopolitical History", Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–9, doi:10.1002/9781444313031.ch1, ISBN 978-1444313031, S2CID 43673269

- "Women's & LGBT Liberation In Revolutionary Russia". Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "The Communist Women's Movement". isreview.org. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- Smith, Sharon (2015). Women and Socialism: Essays on Women's Liberation. Haymarket Books. pp. 12, 199. ISBN 978-1608461806.

- "Abstract – Abortion in Russia". South African Medical Journal. 1935.

- "Women's liberation and socialism". Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- Overy, Richard (2004). Women, the State and Revolution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life, 1917-1936. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521458160.

- Overy, Richard (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0141912240.

- Heer, David (1965). "Abortion, Contraception, and Population Policy in the Soviet Union". Demography. 2: 531–39. doi:10.2307/2060137. JSTOR 2060137. S2CID 46960030.

- Alexandre Avdeev, Alain Blum, and Irina Troitskaya. "The History of Abortion Statistics in Russia and the USSR from 1900 to 1991." Population (English Edition) 7, (1995), 42.

- M., Akrivopoulou, Christina (2015). Protecting the Genetic Self from Biometric Threats: Autonomy, Identity, and Genetic Privacy: Autonomy, Identity, and Genetic Privacy. IGI Global. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4666-8154-5.

- Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- "Abortion law in North Korea". Women on Waves.

- "The Right to Abortion in Tunisia after the Revolution in 2011". Health and Human Rights Journal. 9 December 2019.

- Law on interruption of pregnancy (abortion law), Lovdata. "amendment law of 16 June 1978 no. 66 from 1 January 1979 according to resolution of 1 December 1978" (in Norwegian)

- "Abortion law in Mongolia". Women on Waves.

- "World Abortion Map – Liberalization of Abortion Laws since ICPD" (PDF). Center for Reproductive Rights.

- Law of revision of the Penal Code, Gazette of the Republic of Mozambique, 31 December 2014. "The present law enters into force one hundred and eighty days after its publication." (in Portuguese)

- Law 27.610, Access to voluntary interruption of pregnancy, Ministry of Health of Argentina, 15 January 2021 (in Spanish).

- Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals – Selected and prepared by the United Nations War Crimes Commission https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/Law-Reports_Vol-13.pdf}

- Argentina abortion: Senate approves legalisation in historic decision, BBC News, 30 December 2020.

- "En Uruguay, le Parlement vote la dépénalisation de l'avortement". 17 October 2012 – via Le Monde.

- David Agren (29 September 2019). "'We have made history': Mexico's Oaxaca state decriminalises abortion". Retrieved 30 September 2019 – via The Guardian.

- World Abortion Policies 2013 (Note 26) (archived from the original on 2016-04-15)

- "United Nations Committee Affirms Abortion as a Human Right". The Huffington Post. 25 January 2016.

- World Population Policies 2017: Abortion Laws and Policies, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020.

- "Abortion Act 1967". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- "Laki raskauden keskeyttämisestä 24.3.1970/239". Finlex. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Tiitinen, Aila. "Raskauden keskeytys". Terveyskirjasto. Duodecim. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Findings of termination of pregnancy inspections published". Care Quality Commission. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Table 2: Countries by legal grounds for abortion (recoded), United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Policies 2017: Abortion laws and policies.

- Medical Experts Decry Abkhazia's "Rash" Abortion Ban, Institute for War and Peace Reporting, 8 March 2016.

- World Abortion Policies 2013, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- Law that approves the Angolan Penal Code, Journal of the Republic of Angola, 11 November 2020 (in Portuguese).

- Injunction against the law of access to voluntary interruption of pregnancy, College of Lawyers of Morón, 1 February 2021 (in Spanish).

- Chaco appealed the suspension of the law of voluntary interruption of pregnancy, Página 12, 3 February 2021 (in Spanish).

- Australian abortion law and practice, Children by Choice, 17 June 2020.

- Christmas Island Act 1958, Federal Register of Legislation.

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955, Federal Register of Legislation.

- Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915, Federal Register of Legislation.

- Norfolk Island Act 1979, Federal Register of Legislation.

- Bahrain Penal Code, 1976, Global Abortion Policies Database, World Health Organization.

- Legislative decree no. 7 for 1989 on the practice of human medicine and dentistry, Ministry of Health of Bahrain, Global Abortion Policies Database, World Health Organization.

- Technical procedure for the provision of health services in the framework of the Plurinational Constitutional Sentence 0206/2014, Ministry of Health of Bolivia, 2015. (in Spanish)

- Is the abortion of a rape victim permitted in Congolese law?, Leganews.cd, 29 October 2019. (in French)

- Ordinance 70-158 of 30 April 1970 determining the rules of medical deontology, Leganet.cd. (in French)

- Memorandum no. 04/SPCSM/CFLS/EER/2018 of 6 April 2018 regarding the execution of the provisions of article 14 of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, Official Journal of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 5 June 2008. (in French)

- The total criminalization of abortion in the Dominican Republic, Human Rights Watch, 19 November 2018.

- Act on the autonomy of Åland, Finlex, May 2014.

- Law no. 2001-588 of 4 July 2011 regarding voluntary interruption of pregnancy and contraception, Légifrance. (in French)

- Toward a decriminalisation of abortion in Haiti, Le Figaro, 16 July 2020 (in French).

- Honduras ratifies a reform that prohibits abortion and same-sex marriage, El Periódico Extremadura, 29 January 2021 (in Spanish).

- Abortion in Iranian Legal System, Mahmoud Abbasi, Ehsan Shamsi Gooshki, and Neda Allahbedashti, Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, vol. 13, no. 1, February 2014.

- Abortion, in case of disgrace and unbearable hardship, Islam Quest, 17 Farvardin 1394 (6 April 2015) (in Persian).

- Ivory Coast: advocacy for medical abortions as in the case of rapes, Abidjan.net, 19 July 2020. (in French)

- Law no. 2019-574 carrying the Penal Code, Official Journal of the Republic of Ivory Coast, 10 July 2019. (in French)

- Offences Against the Person Act, Ministry of Justice of Jamaica, 7 April 2014.

- Abortion Policy Review Advisory Group Final Report, Ministry of Health of Jamaica, 19 February 2007.

- Abortion 'right'?, The Gleaner, 25 August 2013.

- Abortion attitudes, training, and experience among medical students in Jamaica, West Indies, Glenmarie Matthews, Jessica Atrio, Horace Fletcher, Nathalie Medley, Leo Walker, and Nerys Benfield, Contraceptive and Reproductive Medicine, 1 May 2020.

- Abortion in Kosovo, an almost impossible mission, Kosovox, 1 July 2017. (in French)

- Penal Code, Lao Official Gazette, 17 May 2017. (in Lao)

- Situation of abortion in the Lao People's Democratic Republic, World Health Organization, 2017.

- Malta does allow for abortions in case of life or death situations, The Malta Independent, 5 May 2013.

- Abortions carried out in certain circumstances in Malta, The Malta Independent, 16 December 2018.

- Aborto legal, Andar. (in Spanish)

- Abortion permit for hospital in Bonaire, Dutch Caribbean Legal Portal, 16 June 2012.

- Termination of pregnancy law, Government of the Netherlands, 19 March 2020. (in Dutch)

- Abortion legislation: information for health practitioners, Ministry of Health of New Zealand, 26 June 2020.

- Regulation on interruption of pregnancy (abortion regulation), Lovdata, 10 May 2013. (in Norwegian)

- Poland puts new restrictions on abortion into effect, resulting in a near-total ban on terminations, CNN, January 28, 2021.

- South Korean court strikes down decades-old abortion ban, National Public Radio, 12 April 2019.

- From Poland to South Korea: 9 abortion rights hotspots in 2021, Thomson Reuters, 31 December 2020.

- Genetic Health Act, Laws and Regulations Database of the Republic of China, 8 July 2009.

- Senators approve amendments to abortion law, The Nation, 26 January 2021.

- Abortion in Northern Ireland: recent changes to the legal framework, House of Commons Library, 26 June 2020.

- Abortion policy in the absence of Roe, Guttmacher Institute, 15 October 2020.

- SB149, Arkansas General Assembly, 2019.

- S1385, Idaho Legislature, 2020.

- HB148, Kentucky General Assembly, 2019.

- Human Life Protection Act, RS 40:1061, Louisiana State Legislature.

- HB126, Missouri General Assembly, 2019.

- HB 1466, North Dakota Legislative Assembly, 2007.

- Chapter 187, South Dakota Legislature, 2005.

- SB1257, Tennessee General Assembly, 2019.

- SB174, Utah State Legislature, 2020.

- Law on the sources of law, Acta Apostolicae Sedis, Supplement for the laws and provisions of Vatican City State, 1 October 2008. (in Italian)

- Title VI. Delicts against human life and freedom, Code of Canon Law, Holy See.

- Penal code for the Kingdom of Italy, 1889, University of Brescia College of Law. (in Italian)

- Abortion and the Catholic Church, Pro-Life Activist's Encyclopedia, American Life League.

- Under Vatican ruling, abortion triggers automatic excommunication, National Catholic Reporter, 17 January 2003.

- Abortion Ordinance, Sovereign Base Areas Gazette, 21 October 1974.

- 46.3903 Authorized abortions, Annotated Code of American Samoa, American Samoa Bar Association.

- Abortions are legal in Guam, but doctors won't perform them, Associated Press, 7 June 2019. "The other U.S. territories in the Pacific – American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands – both prohibit abortions except in very limited circumstances."

- Criminal Code of Anguilla, Government of Anguilla, 15 December 2014.

- Criminal Code of Aruba, Government of Aruba, 3 July 2020. (in Dutch)

- Safe illegal abortion: an inter-island study in the northeast Caribbean, Gail Pheterson and Yamila Azize, c. 2005.

- Criminal Code Act 1907, Bermuda Laws Online, 30 August 2020.

- Criminal Code of the Virgin Islands, Government of the British Virgin Islands, 1997.

- Penal Code, Government of the Cayman Islands, 2019.

- Criminal Code, Government of Curaçao, 2019. (in Dutch)

- Much-needed abortion law is missing, Antilliaans Dagblad, 17 February 2015. (in Dutch)

- Crimes Ordinance 2014, Falkland Islands Government, 2019.

- Why 'restrictive' abortion laws still exist in the Faroe Islands, Nordpolitik, 23 November 2019.

- Crimes Act 2011, Government of Gibraltar, 2019.

- Gibraltar divided ahead of abortion referendum, France 24, 5 March 2020.

- Offenses against the family, Compiler of Laws of Guam, 2018.

- Abortion (Guernsey) Law, 1997, Guernsey Legal Resources.

- Law on abortion, Guernsey Legal Resources, 1910. (in French)

- Rex v. Bourne, Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, 18–19 July 1938.

- Unplanned pregnancy, Family Planning Association of Hong Kong.

- Termination of pregnancy regulations, Hong Kong e-Legislation, 15 February 2017.

- Island's progressive abortion reforms in operation from today, Isle of Man Government, 24 May 2019.

- Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law 1997, Jersey Legal Information Board, 2019.

- Decree-Law no. 59/95/M, Official Press of Macau, 2004. (in Portuguese)

- "Penal Code" (PDF). Government of Montserrat. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2018.

- Attorney General Opinion, Commonwealth Law Revision Commission, 10 March 1995.

- Health clinics performing abortions?, Saipan Tribune, 25 May 2000.

- Pitcairn laws, Government of the Pitcairn Islands.

- Penal Code of Puerto Rico of 2012, with amendments up to 4 August 2020, Government of Puerto Rico. (in Spanish)

- El Pueblo de Puerto Rico v. Pablo Duarte Mendoza, Decisiones de Puerto Rico, 17 April 1980. (in Spanish)

- General Introduction to Legislation, Saint Helena Government.

- Abortion Act (UK) (Tristan da Cunha) Ordinance, 1967, Saint Helena Government, 2017.

- Criminal Code, Government of Sint Maarten, 2013. (in Dutch)

- Crimes, Procedure and Evidence Rules 2003, Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute, 2016.

- Handbook for the Law Commissioners of Tokelau, Government of Tokelau, August 2008.

- Offences Against the Person Ordinance, Government of the Turks and Caicos Islands, 31 March 2018.

- Abortion, 2019 US Virgin Islands Code, Title 14 § 151.

- Network, European Data Journalism. "Even where abortion is legal, access is not granted".

- "Malta now only EU country without life-saving abortion law". The Malta Independent. July 14, 2013.

- In Malta abortions are de facto allowed to save the mother's life through observance of the principle of double effect.[133]

- Ostergren, Robert C.; Le Bossé, Mathias (7 March 2011). The Europeans: A Geography of People, Culture, and Environment. Guilford Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-59385-384-6. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- Kelly, Jon (2016-04-08). "Why are Northern Ireland's abortion laws different to the rest of the UK?". BBC News.

- Jenkins, Philip (11 May 2007). God's continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe's religious crisis. Oxford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-19-531395-6. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- "1973 Danish abortion law Lovitidende for Kongeriget Danmark". Harvard Law. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- Rämö, Aurora (28 May 2018). "Suomessa abortin saa helposti, vaikka laki on yksi Euroopan tiukimmista". Suomen Kuvalehti. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Abortion legislation in Europe" (PDF). International Planned Parenthood Federation. January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "Law 194" (PDF). Columbia. Italian legislation. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- Tamma, Paola (24 May 2018). "Even where abortion is legal, access is not granted". VoxEurop/EDJNet. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Page, Chris. "Northern Ireland abortion and same-sex marriage laws change". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- "Poland abortion: Top court bans almost all terminations". BBC. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Poland 'slammed the door shut' on legal and safe abortions: Human rights experts". UN News. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Worrell, Marc. "Serbia: abortion law". Women on Waves.

- Casey, 505 U.S. at 877.

- Alesha Doan (2007). Opposition and Intimidation: The Abortion Wars and Strategies of Political Harassment. University of Michigan Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780472069750.

- Liptak, Adam (June 29, 2002). "Supreme Court Strikes Down Louisiana Abortion Law, With Roberts the Deciding Vote". The New York times.

- Worrell, Marc. "Abortion Laws Worldwide". Women on Waves.

- "The World's Abortion Laws | Center for Reproductive Rights". reproductiverights.org. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- "Abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean". 10 May 2016.

- Reuters (2019-09-06). "El Salvador will seek third trial of woman accused of 'murdering' stillborn". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- "El Salvador: Rape survivor sentenced to 30 years in jail under extreme anti-abortion law". www.amnesty.org.

- "Jailed for a miscarriage". BBC News.

- "How Doctors Date Pregnancies, Explained". Rewire.

- Choices, NHS. "Abortion". www.nhs.uk.

- "Pregnancy—first day of the last menstrual period". meteor.aihw.gov.au.

- "Estimated Date of Delivery (EDD) Pregnancy Calculator". reference.medscape.com.

- "gestational age".

- Some examples of gestational age calculated from the first day of the last menstrual cycle:[156][157][158][159]}[160]

- "Loi du 17 décembre 2014 portant modification 1) du Code pénal et 2) de la loi du 15 novembre 1978 relative à l'information sexuelle, à la prévention de l'avortement clandestin et à la réglementation de l'interruption volontaire de grossesse". legilux.public.lu.

- For example Luxembourg abortion law states: "Avant la fin de la 12e semaine de grossesse ou avant la fin de la 14e semaine d'aménorrhée[...]" which translates to "Before the end of the 12th week of pregnancy or before the end of the 14th week of amenorrhea".[162]

- helsedepartementet, Sosial–og (18 May 2000). "About the Abortion Act". Government.no.

- "'Health' of the Mother". Newsweek. October 15, 2008.

- "States probe limits of abortion policy". Stateline. June 22, 2006.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. (n.d.). Picketing and Harassment. Retrieved December 14, 2006. Archived November 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1996 [No. 92 of 1996] – G 17602". www.saflii.org.

- "Kenyan charities urge government to quit U.S.-led anti-abortion pact". Reuters. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Abortion Laws of the World. (n.d.). Annual Review of Population Law. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- Appel, JM (2005). "Judicial diagnosis 'conscience' vs. care how refusal clauses are reshaping the rights revolution". Med Health R I. 88 (8): 279–81. PMID 16273974.

- Rahman, Anika; Katzive, Laura; Henshaw, Stanley K (1998). "A Global Review of Laws on Induced Abortion, 1985–1997". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (2): 56–64. doi:10.2307/2991926. JSTOR 2991926. PMID 14627052.

- United Nations Population Division. (2002). Abortion Policies: A Global Review. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- IPPF European Network. (2004). Abortion Legislation in Europe. Retrieved October 27, 2006.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. (2005). law sidebars10.pdf Abortion and the Law: Ten Years of Reform. Retrieved November 22, 2006. (archived from the original on 2009-03-27)

- The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (November 2006). Abortion Laws Around The World. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- Europe's Abortion Laws. (February 12, 2007). BBC News. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- United Nations Population Division. (2007). World Abortion Policies 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- Pollitt, Katha. Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights. Picador, 2015.

External links

- The World's Abortion Laws interactive website of the Center for Reproductive Rights

- The World's Abortion Laws downloadable wallchart, Center for Reproductive Rights

- Pregnant Pause: Summary of Abortion Laws Around the World

- Laws on Abortion in the Second Trimesters, The International Consortium for Medical Abortion (ICMA)

- Abortion: Judicial History and Legislative Response Congressional Research Service

- "Despite overall expansion in the legal grounds for abortion, Policies remain restrictive in many countries" (PDF). Population Facts. Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2014 (1). August 2014.