Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was an engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fleet led by Admiral Franklin Buchanan and three forts that guarded the entrance to Mobile Bay. Farragut's order of "Damn the torpedoes! Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!" became famous in paraphrase, as "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!"

| Battle of Mobile Bay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

.jpg.webp) Battle of Mobile Bay, by Louis Prang. At left foreground is the CSS Tennessee; at the right the USN Tecumseh is sinking. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The battle was marked by Farragut's seemingly rash but successful run through a minefield that had just claimed one of his ironclad monitors, enabling his fleet to get beyond the range of the shore-based guns. This was followed by a reduction of the Confederate fleet to a single vessel, ironclad CSS Tennessee.

Tennessee did not then retire, but engaged the entire Northern fleet. Tennessee's armor enabled her to inflict more injury than she received, but she could not overcome the imbalance in numbers. She was eventually reduced to a motionless hulk and surrendered, ending the battle. With no Navy to support them, the three forts also surrendered within days. Complete control of lower Mobile Bay thus passed to the Union forces.

Mobile had been the last important port on the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi River remaining in Confederate possession, so its closure was the final step in completing the blockade in that region.

This Union victory, together with the capture of Atlanta, was extensively covered by Union newspapers and was a significant boost for Abraham Lincoln's bid for re-election three months after the battle.

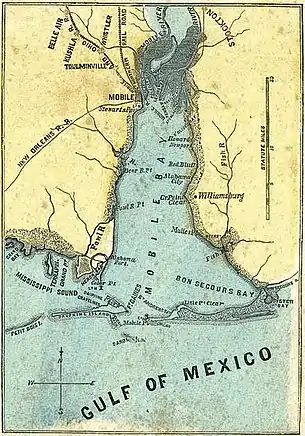

Mobile and Mobile Bay

The city of Mobile is situated near the head of Mobile Bay, where a natural harbor is formed by the meeting of the Mobile and Tensaw rivers. The bay is about 33 mi (53 km) long; the lower bay is about 23 mi (37 km) at its greatest width. It is deep enough to accommodate ocean-going vessels in the lower half without dredging; above the mouth of Dog River the water becomes shoal, preventing deep-draft vessels from approaching the city.

The mouth of the bay is marked on the east by a long narrow peninsula of sand, Mobile Point, that separates Bon Secour Bay, where the Bon Secour River enters the larger bay, from the gulf. The point ends at the main channel into Mobile Bay, and here the United States government erected a pre-war fort to shield Mobile from enemy fleets.

Across the entrance, the line of the peninsula is continued in a series of barrier islands, beginning with Dauphin[lower-alpha 2] Island. Northwest of Dauphin Island is Little Dauphin Island, then a series of minor islands that are interrupted by a secondary entrance to the bay, Grant's Pass.[lower-alpha 3] A few other small islands and shoals lie to the south of Dauphin Island, defining the main channel for as much as 10 mi (16 km) south of the entrance.[2]

Rather early in the war, the Confederate government decided not to defend its entire coastline, but rather to concentrate its efforts on a few of its most important ports and harbors.[3] Following the loss of New Orleans in April 1862, Mobile became the only major port in the eastern Gulf of Mexico that needed to be defended.[lower-alpha 4]

The city subsequently became the center for blockade running on the gulf. Most of the trade between the Confederacy, Havana, and other Caribbean ports passed through Mobile.[4] A few attempts were mounted to break the blockade, but they were not large enough to have lasting impact.[5] Among the most embarrassing episodes of the war for the U.S. Navy was the passage of the raider CSS Florida through the blockade into Mobile Bay on September 4, 1862; this was followed by her later escape through the same blockade on January 15, 1863.[6]

Although the orders given to Flag Officer David G. Farragut when he was assigned to command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron had included instructions to capture Mobile as well as New Orleans, the early diversion of the squadron into the campaign for the lower Mississippi meant that the city and its harbor would not receive full attention until after the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863.

Given respite by the Union strategy, the Confederate Army improved the defenses of Mobile Bay by strengthening Fort Morgan and Fort Gaines at the entrance to the bay. In addition, they set up Fort Powell, a smaller work that guarded the Grant's Pass channel.[7] Grant's Pass was also obstructed by a set of piles and other impediments, which had the effect of diverting the tidal flow to Heron Pass.[8] [lower-alpha 5]

Confederate defenses

Land

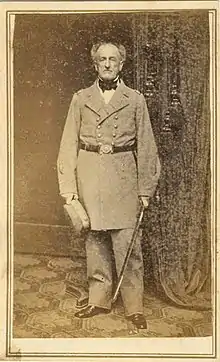

Mobile and Mobile Bay were within the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, led by Major General Dabney H. Maury. Although Mobile was the site of the department headquarters, Maury did not exercise immediate command of the forts at the entrance to the bay, and he was not present during the battle and ensuing siege. Local command was entrusted to Brigadier General Richard L. Page.

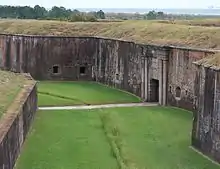

The primary contribution of the Confederate Army to the defense of Mobile Bay was the three forts. Fort Morgan was a masonry structure dating from 1834.[10] The fort mounted 46 guns, of which 11 were rifled. Its garrison numbered about 600.[11]

Across the main channel from Fort Morgan on Dauphin Island was Fort Gaines, containing 26 guns, and with a garrison of about 600. When Page was not present, command of the fort fell to Colonel Charles D. Anderson.[lower-alpha 6]

At the western end of the bay was Fort Powell, smallest of the three, with 18 guns and about 140 men. It was commanded in Page's absence by Lieutenant Colonel James M. Williams.[12] All three forts were flawed in that their guns were unprotected against fire from the rear; in addition, forts Powell and Gaines lacked adequate traverses.[13]

The raw numbers of troops available do not indicate how effectively they would fight. The war was already winding down, and assertions were made that the morale of the soldiers was bad. The judgment is hard to quantify, but it would explain at least in part the poor performance of the defenders.[14]

The Confederate Torpedo Bureau, directed by Major General Gabriel J. Rains, contributed a passive weapon to the defense. Men of the bureau had planted 67 "torpedoes" (naval mines) across the entrance, leaving a gap on the eastern side of the channel so blockade runners and other friendly vessels could enter or leave the harbor.[15] The minefield was well marked by buoys, which Farragut knew well.[16] Its purpose was not necessarily to sink enemy vessels trying to enter, but rather to force them to steer close to Fort Morgan and its guns.

Sea

The Confederate Navy likewise used the time they were given to improve the defense. Three small sidewheel gunboats of traditional type were stationed in the bay: CSS Selma, carrying four guns; Morgan, with six guns; and Gaines, also with six guns. In addition to these was the ironclad ram CSS Tennessee, which, though carrying only six guns, was a far more impressive fighting machine by virtue of her armor.[17]

Tennessee had been built on the Alabama River near the town of Selma. Her guns were prepared under the direction of Commander Catesby ap Roger Jones, who had commanded CSS Virginia (ex-USS Merrimack) in her famous duel with USS Monitor on March 9, 1862, the second day of the Battle of Hampton Roads.[18] Jones succeeded to command of Virginia after her original commander, Franklin Buchanan, was wounded the previous day. Buchanan had been promoted to the rank of admiral for his exploits that day, the first admiral in the Confederacy. Admiral Buchanan was now in command of the small Confederate flotilla at Mobile.[19][lower-alpha 7]

Launched before her machinery and guns were in place, Tennessee was towed down to Mobile Bay for completion. Once that was done she had to cross the Dog River Bar to get into the lower bay. Tennessee drew 13 ft (4.0 m), but the bar had only 9 ft (2.7 m) of water at high tide. To get her across, workers had to build a set of caissons, called "camels" by shipbuilders. These were fitted to her sides and pumped out, and barely lifted the ship enough to clear the bar. On May 18, 1864, she finally entered the lower bay.[21]

Tennessee was the only armored vessel that the Confederate Navy put into lower Mobile Bay,[lower-alpha 8] but there were plans for others. Buchanan hoped that he would have as many as eight, including a pair of floating batteries, with which he could challenge the Union blockade, attack Pensacola and perhaps even recapture New Orleans.[23] The manufacturing and transportation facilities of the South were not capable of this ambitious program, however. Some of the projected fleet were completed in time to defend Mobile after the lower bay had been lost, but they were not there when most needed. Nevertheless, they imparted some urgency to Farragut's plans to maintain the blockade.[24]

The United States

Union Navy

The man who led the Union fleet at Mobile Bay was Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, no longer Flag Officer Farragut. The U.S. Navy had undergone an organizational change in the second year of the war, one feature of which was the creation of the rank of Rear Admiral. The new rank implied that the ships of the navy would be employed as members of a fleet, not simply as collections of vessels with a common purpose.

The ships that made up his attacking fleet were of several distinct types, including some that had not even existed when the war began. Of the 18 vessels selected, eight were conventional wooden-hulled ships carrying large numbers of guns that fired broadside. Four of these had been with the West Gulf Blockading Squadron from the start (flagship Hartford, Brooklyn, Richmond, and Oneida) and had fought in its battles on the Mississippi. Two smaller gunboats had likewise been with Farragut since the capture of New Orleans: Kennebec and Itasca.[25]

Galena was now very much like the others, but she had begun life as an experimental ironclad. Her armor had been found to be more hindrance than help, so it was removed.[26] Three were double-enders (Octorara, Metacomet, and Port Royal), a type of warship that had been developed during the war to navigate the tortuous channels of the interior rivers. Finally, four were representatives of the New Navy: ironclad monitors. Of these, Manhattan and Tecumseh were improved versions of the original Monitor, featuring two large guns in a single turret. The Chickasaw and Winnebago were twin-turreted river monitors of light draft; each mounted four guns that were smaller than those carried by the other two.[27]

Union Army

Army cooperation was needed to take and hold the enemy forts. The commander of the Military Division of West Mississippi was Major General Edward Richard Sprigg Canby, a career soldier with whom Farragut worked in planning the attack on Mobile. He calculated that 5,000 soldiers could be taken from other responsibilities in the division, enough to effect a landing behind Fort Morgan and cut it off from communication with Mobile. Their plans were undercut, however, when General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant made an urgent call for troops to be sent to the Virginia theater, then entering its critical phase.

Canby then believed that he could spare no more than 2,000, not enough to invest the largest fort but enough to take Dauphin Island and thereby secure contact between the fleet inside the bay and their support in the gulf. Canby and Farragut recognized that they would not be able to threaten Mobile, but possession of the lower bay would be of great enough use to the blockading fleet that the projected attack should not be canceled.[28]

Communication would be necessary between the fleet and the landing force, so Canby suggested that a contingent of his signal corpsmen be distributed among the major ships of Farragut's attacking force. Farragut accepted the offer. This almost casual mingling of the services was found quite useful during the battle.[29]

On August 3, 1864, 1,500 men were landed approximately 15 miles west of the fort in preparation for the Siege of Fort Gaines, while under protection from one of Farragut's flotillas. The troops consisted of infantry detachments from the 77th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 34th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 96th Ohio Infantry, and 3rd Maryland Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, with General Gordon Granger as commander. The troops then marched toward Fort Gaines. On the evening of August 4, they entrenched and formed their skirmish line less than a half mile away.[30]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle and siege

The army landing force under Granger was ready to launch the attack on August 3, but Farragut wanted to wait for his fourth monitor USS Tecumseh, expected at any moment but delayed at Pensacola. The admiral almost decided to proceed with only three monitors, and the army went ashore on Dauphin Island, acting under a misapprehension of naval intentions. The fleet was not ready to move yet, so the defenders were able to rush additional forces to Fort Gaines. After the battle, Farragut concluded that the delay had actually worked to the advantage of the Federal forces, as the reinforcements were not great enough to have any effect on the battle, but they were included in the surrender.[31]

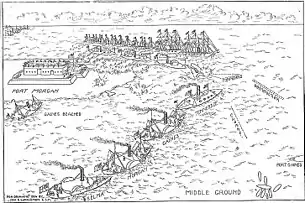

While the army was going ashore, Tecumseh made her belated appearance and Farragut made his final dispositions for the fleet. The 14 wooden-hulled vessels would be lashed together in pairs, in a reprise of a tactic that the admiral had used earlier at the Battle of Port Hudson at Port Hudson, Louisiana.[lower-alpha 9] The intent was that, if a ship were to be disabled by battle damage to her engines, her partner would be able to keep her moving.

The monitors would form a column and lead the way into the bay, moving in close to Fort Morgan on the right side of the channel as they went in. The other ships would form a separate double column and pass on the port side of the monitors, so that the armored ships would shield their wooden sisters from the guns of the fort. When the Confederate fleet made its expected appearance, the monitors would move to attack the armored Tennessee, while the rest of the fleet would fight the faster gunboats.[33]

Passing the forts

At dawn on August 5, conditions were nearly ideal for the attack. The tide was running in, so Farragut had his ships reduce steam pressure in order to minimize damage if their boilers were hit; he relied on the current to give them speed. The southwest breeze that sprang up would carry smoke from the guns away from the fleet and into the faces of the artillerymen in Fort Morgan.

The fleet approached the fort with Tecumseh, Manhattan, Winnebago, and Chickasaw in order leading the way. The second column was led by Brooklyn lashed to Octorara. Brooklyn had the lead because she carried four chase guns that could fire forward, while the other large ships had only two. She was also fitted with a device for removing mines, referred to as a "cowcatcher" by Farragut in his reports.[34] Following were Hartford and Metacomet, Richmond and Port Royal, Lackawanna and Seminole, Monongahela and Kennebec, Ossipee and Itasca, and Oneida and Galena.[35]

The Confederate ships were ready for the attack, and they moved into position to intercept the Union fleet just beyond the minefield. At 6:47 a.m., Tecumseh fired the first shot, the forts replied, and the action became general.[36] The ships in the second column (except for Brooklyn) could not reply to the guns of the Confederate vessels, so they had to concentrate on the fort. Much of the damage done to the Federal fleet was caused by the enemy ships, perhaps because the fire from the fort was suppressed.[37][lower-alpha 10]

.jpg.webp)

Shortly after the start of the action, monitor Tecumseh moved past the fort and toward Tennessee, apparently in obedience to that part of her orders. Commander Tunis A. M. Craven either disregarded or forgot the instruction to stay to the east of the minefield, so he took his ship directly across. Almost immediately, a torpedo went off under her hull, and she filled with water and sank in two or three minutes. Only 21 of her crew of 114 were saved. Craven was among those lost, so he could not explain his decisions.[lower-alpha 11]

Captain James Alden of Brooklyn was apparently confused by conflicting orders, to stay on the port side of the monitors and to stay to the right of the minefield, so he stopped his ship and signaled Farragut for instructions. Farragut would not stop the flagship; he ordered Captain Percival Drayton to send Hartford around Brooklyn and into the lead of the column. This took the ship into the torpedoes that had just sunk Tecumseh, but Farragut was confident that most of them had been submerged too long to be effective. His gamble paid off, and the entire column of 14 warships passed through unharmed.[39]

Tennessee lacked the speed needed to ram the Union vessels as they passed, allowing Farragut to order some of his small, faster gunboats to attack the three Confederate gunboats. Metacomet, unleashed from Hartford, captured Selma. Fire from the gunboats holed Gaines, and she would have sunk had she not been beached; she was then burned by her crew. Morgan put up no resistance, but fled to the protection of the guns of Fort Morgan; next night she crept through the anchored Union fleet and escaped to Mobile.[40]

Clash with CSS Tennessee

_(1899)_(14780685394).jpg.webp)

Farragut expected Tennessee to take shelter under the guns of Fort Morgan while he rested his ships and assessed battle damage in the middle of the bay, but Buchanan instead decided to take on the entire Federal fleet single-handed. Possibly he hoped to repeat the ramming tactics that had been so successful at Hampton Roads two years earlier; Buchanan did not explain his reasoning.

This time, the ships that he was facing were in motion, and he had to contend with three monitors, not one. Tennessee was so slow that she became the target of ramming rather than her opponents. Several of the Federal sloops managed to ram, including Monongahela, which had been fitted with an iron shield on her bow just for this purpose. None of the collisions harmed the ironclad; in every case, the ramming vessel suffered more. Shots from Farragut's fleet bounced off Tennessee's armor, but Tennessee's fire was ineffective due to inferior powder and multiple misfires.[41]

The balance was tilted finally when two monitors arrived. Tennessee was already almost motionless, her smokestack shot away and so unable to build up boiler pressure. Her rudder chains were parted so that she could not steer. Furthermore, some of the shutters on her gun ports were jammed, rendering the guns behind them useless. Chickasaw took up position at her stern, and Manhattan began to pummel the ram with her 15 in (380 mm) guns. The heavy shot bent in the iron shield and shattered its oak backing.

Fragments killed or wounded some of the crew; one of the casualties was Admiral Buchanan himself, who suffered a badly broken leg. No longer able to fight, Commander James D. Johnston, captain of Tennessee, requested and received permission from the wounded admiral to surrender.[42] A little more than three hours had elapsed since Tecumseh had fired the first shot.

Forts Powell and Gaines

With the fleet no longer facing opposition from the Confederate Navy, Farragut could pay some attention to the forts. He dispatched monitor Chickasaw to throw a few shells at Fort Powell and then to assist the troops ashore at Fort Gaines. Although neither fort suffered significant casualties or damage, the bombardment was sufficient to reveal the vulnerability of each to fire from the rear.

At Fort Powell, Lt. Col. Williams asked for instructions from Brig. Gen. Page. Page responded with ambiguous orders that may have been appropriate for spirited troops, but were disastrous when issued to men as seemingly demoralized as those at Fort Powell: "When no longer tenable, save your garrison. Hold out as long as you can." Williams was convinced that resistance was futile, so he spiked his guns and blew up his magazines; then he and his garrison waded to the mainland and made their way to Mobile.[43]

Col. Anderson at Fort Gaines held out longer, although he faced a more formidable foe. Granger's soldiers vastly outnumbered his own, no matter whose figures for the garrison are accepted. The Union troops could bring their artillery up to close range with impunity, being shielded behind the sand dunes of Dauphin Island. In position, they were able to take in reverse two guns that fired on Farragut's fleet when it was entering the bay.

In the judgment of an engineering officer who inspected the fort after the Union army had taken possession, "It was utterly weak and inefficient against our attack (land and naval), which would have taken all its fronts in front, enfilade, and reverse."[44] Recognizing that his situation was hopeless, Anderson opened communication with Granger and Farragut under a flag of truce; ignoring orders from Page forbidding him to do so (and eventually removing him from command), he surrendered the fort on August 8.[45]

Siege of Fort Morgan

As soon as the surrender of Fort Gaines was completed, Granger moved his force from Dauphin Island to the narrow strip of mainland behind Fort Morgan, where they were landed without opposition about 4 mi (6.4 km) away, well out of range of its guns. The fort was thus immediately invested, cut off from all communication with Mobile.

Granger set about taking the fort by regular approaches — that is, establishing a sequence of trenches or other protective lines drawn ever closer to the objective, until finally its walls could be breached and it could be taken by assault. His first line was a gift, a line of trenches 1,400 yd (1,300 m) from the fort that had been prepared by the garrison of the fort and then for some reason abandoned. It was a little farther than he would have liked, but it served quite well. Additional parallels were built with little interference, as the laborers could work behind the sand dunes.

While this was going on, monitors Winnebago, Chickasaw, and Manhattan were engaging in occasional bombardment. They were later joined by the former CSS Tennessee, captured on August 5, since repaired, and now renamed USS Tennessee. The most serious hindrance to the advance in this period was the weather; a storm on August 20 halted work for a while, and left standing water in low places. The fort was subjected to a day-long bombardment on August 22 from 16 siege mortars, 18 guns of various sizes, and the fleet, the monitors and Tennessee at short range and the rest of the ships at long range.[46]

Inside the fort, Brig. Gen. Page feared that the bombardment would endanger his magazines, which contained 80,000 lb (36,000 kg) of powder. To avoid the risk, he had the powder brought out and flooded. That night, the magazines were indeed threatened when the woodwork of the citadel caught fire. The fire brought an increase in the rate of bombardment, and was extinguished only with great effort.

Feeling now that further resistance was useless, on August 23 Page ordered his remaining guns spiked or otherwise destroyed as far as possible. At 6 AM, he ordered the white flag raised, and the siege was over.[47]

Incidents of the battle

Farragut lashed to the rigging

An anecdote of the battle that has some dramatic interest has it that Farragut was lashed to the mast during the passage of Fort Morgan. The image that it brings to mind is of absolute resolve: if his ship were to be sunk in the battle, he would go down with her. The truth, however, is more prosaic. He was indeed lashed to the rigging of the mainmast, but it was a precautionary move rather than an act of defiance. It came about after the battle had opened and smoke from the guns had clouded the air. In order to get a better view of the action, Farragut climbed into Hartford's rigging and soon was high enough that a fall would certainly incapacitate him and could have killed him. Seeing this, Captain Drayton sent a seaman aloft with a piece of line to secure the admiral. He demurred, saying, "Never mind, I am all right," but the sailor obeyed his captain's orders, tying one end of the line to a forward shroud, then around the admiral and to the after shroud.[48]

Later, when CSS Tennessee made her unsupported attack on the Federal fleet, Farragut climbed into the mizzen rigging. Still concerned for his safety, Captain Drayton had Flag Lieutenant J. Crittenden Watson tie him to the rigging again.[49] Thus, the admiral had been tied to the rigging twice in the course of the battle.

"Damn the torpedoes"

Most popular accounts of the battle relate that Brooklyn slowed when Tecumseh crossed her path, and Farragut asked why she was not moving ahead. The reply came back that naval mines (then called "torpedoes") were in her path—to which he allegedly replied, "Damn the torpedoes." The story did not appear in print until several years later, and some historians question whether it happened at all.[50]

Some forms of the story are highly unlikely; the most widespread is that he shouted to Brooklyn, "Damn the torpedoes! Go ahead!" Men present at the battle doubted that any such verbal communication could be heard above the din of the guns. More likely, if it happened, is that he said to the captain of Hartford, "Damn the torpedoes. Four bells,[lower-alpha 12][51] Captain Drayton." Then he shouted to the commander of Metacomet, lashed to Hartford's side, "Go ahead, Jouett, full speed." The words have been altered in time to the more familiar, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!"[52]

Army signals

Prior to the battle, the Army and Navy used completely different signals. The Navy used a cumbersome system of colored flags that would impart messages that had to be decoded, whereas the Army was experimenting with a far simpler wigwag[lower-alpha 13] system, recently developed by Col. Albert J. Myer. In order to communicate with Army forces ashore after the fleet was safely inside Mobile Bay, several members of the fledgling Signal Corps were put on the major ships of Farragut's fleet.[53] They were expected to stay out of the way until they were needed; those on Hartford, for example, were assigned to assist the surgeon, so they were stationed below decks.

When Brooklyn encountered her difficulties with Tecumseh and the minefield, Captain Avery of Brooklyn wanted clarification of his orders more rapidly than could be done with navy signals, so he asked his army representatives to relay his question to the flagship. In order to read the message, the signal corpsmen on Hartford were brought up from below, and they stayed up through the rest of the fight.[54] Their contribution was acknowledged by Farragut.[55]

Court martial of Page

After General Page surrendered Fort Morgan, the victors found that all of the fort's guns had been spiked, and gun carriages and other supplies destroyed. Some believed that much of the damage had been done while the white flag was flying, in violation of the rules of war as they were then understood. The belief was so strong that Canby made a formal accusation, and Page was tried in New Orleans by a three-man council of war to consider the charges. After reviewing the evidence, the court found him not guilty of the charges.[56]

Aftermath

The Battle of Mobile Bay was not bloody by standards set by the armies of the Civil War, but it was by naval standards. It was only marginally, if at all, less bloody than the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip and the Battle of Hampton Roads. The Federal fleet had lost 150 men killed and 170 wounded; on the Confederate ships, only 12 were dead and 19 wounded.[57] Union Army losses were very light; in the siege of Fort Morgan, only one man was killed and seven wounded.[58] Confederate losses, though not stated explicitly, seem to have been only slightly greater.[59]

The continued presence of a Union Army force near Mobile constrained the Confederate Army in its last desperate campaigns. Maury realized that the numbers opposite him were inadequate for an attack, but the loss of Mobile would have been such a severe blow to the public mood that he would not send his guns or spare troops to support other missions.[60]

This was particularly important to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, who was at that time engaged in the Atlanta campaign. Because Mobile remained unconquered the significance of Farragut's victory initially had little effect on Northern public opinion. As time passed and a sequence of other Union victories seemed to show that the war was winding down, the battle began to loom larger.

When Atlanta fell, in the words of historian James M. McPherson, "In retrospect the victory at Mobile Bay suddenly took on new importance as the first blow of a lethal one-two punch."[61] The dispersal of Northern gloom assured President Abraham Lincoln's re-election in what was regarded as a referendum on continuation of the war.

With the capture of Fort Morgan, the campaign for the lower Mobile Bay was complete. Canby and Farragut had already decided before the first landings on Dauphin Island that the army could not provide enough men to attack Mobile itself; furthermore, the Dog River Bar that had impeded bringing Tennessee down now prevented Farragut's fleet from going up. Mobile did come under combined army-navy attack, but only in March and April 1865, after Farragut had been replaced by Rear Adm. Henry K. Thatcher. The city finally fell in the last days of the war.[62]

A number of Civil War-era shipwrecks from the battle and its aftermath remain in the bay into the present, including American Diver, CSS Gaines, CSS Huntsville, USS Philippi, CSS Phoenix, USS Rodolph, USS Tecumseh, and CSS Tuscaloosa.[63]

See also

References

- Anderson, Bern, By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War. Alfred A. Knopf, 1962; reprint, Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80367-4

- Calore, Paul, Naval Campaigns of the Civil War. Jefferson, N. C.: McFarland, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7864-1217-4

- Duffy, James P., Lincoln's Admiral: The Civil War Campaigns of David Farragut. Wiley, 1997. ISBN 0-471-04208-0

- Faust, Patricia L., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Harper and Rowe, 1986. ISBN 0-06-181261-7

- Friend, Jack, West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1-59114-292-8

- Johnson, Robert Underwood and Clarence Clough Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Century, c. 1894. Reprint ed., Castle, n.d.

- Johnston, James D., "The Ram 'Tennessee' at Mobile Bay." Vol. 4, pp. 401–406.

- Kinney, John Coddington, "Farragut at Mobile Bay." Vol. 4, pp. 379–400.

- Marston, Joseph, "The lashing of Admiral Farragut in the rigging." Vol. 4, pp. 407–408.

- Page, Richard L., "The Defense of Fort Morgan." Vol. 4, pp. 408–410.

- Watson, J. Crittenden, "The lashing of Admiral Farragut in the rigging." Vol. 4, pp. 406–407.

- Levin, Kevin M., "Mobile Bay", Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Luraghi, Raimondo, A History of the Confederate Navy. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996. ISBN 1-55750-527-6

- McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom. Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0

- Musicant, Ivan, Divided Waters: the Naval History of the Civil War. HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 0-06-016482-4

- Scharf, J. Thomas, History of the Confederate States Navy From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel; etc. New York, Rogers & Sherwood, 1887; reprint, Gramercy, 1996.

- Simson, Jay W., Naval Strategies of the Civil War: Confederate Innovations and Federal Opportunism. Nashville, Tenn.: Cumberland House, 2001. ISBN 1-58182-195-6

- Still, William N. Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Vanderbilt University Press, 1971. Reprint, University of South Carolina Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87249-454-3

- Tucker, Spencer, Blue & Gray Navies: The Civil War Afloat. Naval Institute Press, 2006. ISBN 1-59114-882-0

- United States. Naval History Division, Civil War Naval Chronology, 1861–1865. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1961–65.

- Wise, Stephen R., Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War. University of South Carolina Press, 1988. ISBN 0-87249-554-X

Notes

Abbreviations used in these notes:

- ORA (Official records, armies): The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

- ORN (Official records, navies): Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 402.

- Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, p. 20. Kinney, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 384, map.

- Luraghi, History of the Confederate Navy, p. 187. ORA I, v. 6, pp. 398, 826, 835.

- Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, pp, 168–180; appendices 11–14.

- Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy, pp. 537–549.

- Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy, pp. 790–791.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 51. Kinney, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 385.

- ORN I, v. 21, p. 528.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 189.

- Faust, Encyclopedia of the Civil War, entry for Fort Morgan.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, pp. 419–420.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 441.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 74–75, 120–122. ORA I, v. 39/1, pp. 410, 411.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 57–58. ORN I, v. 21, p. 364. ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 414.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 137–139. ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 433.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 67, 125. ORN I, v. 21, p. 373.

- Opposing forces (Confederate), Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 400.

- Johnston, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 401. But see Still, Iron Afloat, p. 196.

- Still, Iron Afloat,, p. 190.

- Still, p. 94.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 202.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 80–81, 192.

- Cahore, Naval campaigns of the Civil War, p. 187.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 190–196.

- Battles and Leaders, v. 2, p. 74.

- Tucker, Blue and Gray Navies, p. 37.

- Opposing forces (Union), Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 400

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 76. ORN I, v. 21, pp. 380, 388.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 76. Kinney, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 381.

- Parker, The Battle of Mobile Bay, pp. 17-18.

- ORN I, v. 21, p. 416.

- Anderson, By Sea and by River, p. 145.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 154. ORN I, v. 21, pp. 416–417.

- ORN I, v. 21, p. 403.

- Calore, Naval Campaigns of the Civil War, p. 189.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 166. ORN I, v. 21, p. 415–418.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 168. ORN I, v. 21, p. 418.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 178.

- Duffy, Lincoln's Admiral, pp. 240–248.

- Anderson, By Sea and by River, pp. 242–243.

- ORN I, v. 21, p. 418.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 219–221. ORN I, v. 21, p. 419.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 228–229. ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 436.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 410.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 236. ORA I, v. 39/1, pp. 417–418.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 239. ORA I, v. 39/1, pp. 411–414.

- Page, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, pp. 408–410. Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 239–240.

- Duffy, Lincoln's Admiral, p. 243.

- Watson, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 407.

- Anderson, By Sea and by River,, p. 242.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 187.

- Duffy, Lincoln's admiral, pp. 247–248.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 124, 178. ORN I, v. 21, p. 525.

- Kinney, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, pp. 379–400. Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, pp. 123–124, 170, 217–218.

- ORN I, v. 21, p. 518.

- Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 251. ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 405.

- Musicant, Divided Waters, p. 324.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 404.

- Page, Battles and Leaders, v. 4, p. 410.

- ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 428.

- McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 775.

- Faust, Encyclopedia of the Civil War, entry "Mobile, Siege of."

- Gaines, W. Craig (2008). Encyclopedia of Civil War Shipwrecks. LSU Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-8071-3274-6.

- The start date is formal; it is the day the landing force went aboard their transports. The first day of contact between opposing forces was August 4.

- Sometimes spelled Dauphine in contemporary accounts.

- Grant Pass in present-day nomenclature.

- The only other remaining port was St. Marks, Florida, which was too small for most steamships, and furthermore lacked rail connections with the interior. See Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, pp. 80–81.

- The piles also thwarted early CS Navy plans for cooperation between the defenses of Mobile and New Orleans.[9]

- Maury's report, ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 417. Canby asserted in his report (ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 403) that 818 enlisted men and 46 officers were captured with the surrender of Fort Gaines; this number is quoted by Friend, West Wind, Flood Tide, p. 156. The discrepancy may be caused by the failure of Maury to include in his accounting reinforcements he rushed to the fort when he thought that the invaders could be repulsed (ORA I, v. 39/1, p. 417). On the other hand, all such numbers in the Civil War are unreliable.

- Chief Naval Constructor John L. Porter was active in the design of both Tennessee and Virginia. This is not surprising, as most Confederate ironclads were prepared from Porter's basic designs.[20]

- Early in the war, Alabama had acquired steamer Baltic and converted her into an ironclad ram, to serve in and near Mobile Bay. She was never effective, however, and her armor was removed to be used on another vessel, CSS Nashville.[22]

- Farragut had tried to pass the Confederate works at Port Hudson on March 14, 1863, in support of the Vicksburg campaign. Only two of his seven ships got through, but the attempt was regarded as a success nonetheless.[32]

- The disposition of the Confederate ships was in what came to be known as "crossing the T."

- In an early account of the battle, Rear Admiral Foxhall A. Parker speculated that the poor steering of his monitor forced Craven's hand.[38]

- "Four bells" was a signal to the engine room calling for full power.

- Akin to but not the same as semaphore.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Mobile Bay. |

- Battle of Mobile Bay Page: Battle maps, photos, history articles, and battlefield news (CWPT)

- Paintings of the battle

- "Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Battle of Mobile Bay in the Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Mobile Bay order of battle

.svg.png.webp)