Partisan Ranger Act

The Partisan Ranger Act was passed on April 21, 1861 by the Confederate Congress. It was intended as a stimulus for recruitment of irregulars for service into the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. The Confederate leadership, like the Union leadership, later opposed the use of irregular warfare out of fear that the lack of discipline among rival guerrilla groups could spiral out of control. On February 17, 1864, the law was repealed after pressure from General Robert E. Lee and other Confederate regulars.

.jpg.webp)

Only two partisan rangers groups were exempt and allowed to continue to operate to the very end of the war: Mosby's Raiders and McNeill's Rangers. Both independent partisan rangers operated in the western counties of Virginia and were known to exercise military discipline when they conducted raids.

Background

Initially, Confederate President Jefferson Davis did not approve of irregular warfare since the guerillas were too hard to control and because it reduced the number of able men eligible to serve in the regular army. However, after conventional Confederate forces were driven out of western Virginia in the summer and early fall of 1861, pro-Confederate unconventional combatants remained active in the region. Virginia Governor John Letcher issued a proclamation calling to "raise such a force as would enable General Floyd to recover Western Virginia from the dominion of the invader."[1] On March 27, 1862, Virginia Legislature passed an Act to Authorize the Organization of ten or more Companies of Rangers, which became known as the Virginia Ranger Act.[2]

On April 8, 1862, a bill was introduced to the 1st Confederate States Congress by a member of the Confederate Congress from Virginia to allow raising a force of partisan rangers with a five dollar bounty for every Union soldier killed. The Confederate Senate Congressional Military Committee removed the bounty provision and instead proposed permitting future partisan rangers to receive the same pay as regular Confederate soldiers on conditions that they were to become subjects to near all Confederate States Army regulations. In one exception partisan rangers were authorised to sell captured arms and munitions to Confederate Quartermaster-General's Department.[3]

The result was the Confederate Congress passed the Partisan Ranger Act on April 21, 1862.

Content

There were two purposes of the Partisan Ranger Act. One was to take control over guerilla warfare and employ it for the Confederate States advantage. The other purpose was to promote the use of guerilla warfare in the areas that were beyond the reach for the Confederate Army.

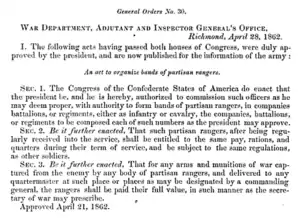

According to Document 94 of the Congress of the Confederate States, the Partisan Ranger Act[4][5] reads as follows:

Section 1. The congress of the Confederate States of America do enact, That the president be, and he is hereby authorized to commission such officers as he may deem proper with authority to form bands of Partisan rangers, in companies, battalions, or regiments, to be composed of such members as the President may approve.

Section 2. Be it further enacted, that such partisan rangers, after being regularly received in the service, shall be entitled to the same pay, rations, and quarters during the term of service, and be subject to the same regulations as other soldiers.

Section 3. Be its further enacted, That for any arms and munitions of war captured from the enemy by any body of partisan rangers and delivered to any quartermaster at such place or places may be designated by a commanding general, the rangers shall be paid their full value in such manner as the Secretary of War may prescribe.

The Partisan Ranger Act led to the recruitment of irregular soldiers into the Confederate Army. Partisan rangers thus had the same rules, supplies, and pay as the regular soldiers of the army, but they would be acting independently and would be detached from the rest of the army. The partisan rangers were to gather intelligence and take supplies away from the Union Army. Anything they brought back would be given to the quartermaster, a military officer who was in charge of providing food, clothing, and other necessities; in return, they would get paid.

The Partisan Ranger Act drew many Southern men who were reluctant to serve in a regular army but were eager to enroll in a partisan corps with the same pay as conventional soldiers.[6] The unintended consequences of the Partisan Ranger Act were beliefs that all forms of guerilla warfare were now approved, including violence towards civilians as a fighting method.[7]

Outcome

By early 1864, after 22 months, the Partisan Ranger Act had completely fallen off track due to Confederate guerilla violent activity. It was repealed on February 17, 1864, after Robert E. Lee persuaded the Confederate Congress to do so. That did not mean the end of guerilla warfare entirely, but it meant the end of the Confederate government trying it out as new military strategy. An experiment to make guerilla warfare a significant benefit for the South had failed,

The Partisan Ranger Act was meant to channel unrestrained and unconventional violence from the amorphous unproductive form outside the purview of government control into a form that, Confederate leaders hoped, would rationally advance the Confederacy’s war goals. ... When partisan rangers’ military failures no longer rationally advanced the Confederacy’s war goals, the Confederate leadership reverted to the prevailing orthodox position that unconventional combatants were not soldiers under the laws of war.[3]

Legacy

The Partisan Ranger Act may have failed in the very end, but it played a certain role in the American Civil War. Multiple partisan rangers groups and units proved to be useful in staging independent raids and collecting information about movements of the Union Army, as well as conducting reconnaissance and skirmishes during the battles. Altogether, the partisan rangers were able to somewhat distract and hamper the Union Army operations throughout the war until it developed successful counter-strategies in 1864.[8]

References

- Message of the Governor of Virginia, and Accompanying Documents by Virginia Governor, 1860-1864, Document No. 7.—Governor's Communication Relative to the States Troops, p. 3.

- Chap. 26.—An Act to Authorize the Organization of ten or more Companies of Rangers, Virginia. General Assembly. Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: 1862

- Rutherfurd, Winthrop. The Partisan Ranger Act: The Confederacy and the Laws of War, Louisiana Law Review, Volume 79, Number 3, Spring 2019, p. 809.

- Frank Moore, The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, with Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, Etc, Volume 8 New York: G. P. Putnam, 1865 p. 422

- The Statutes at Large of the Confederate States of America, Commencing with the First Session of the First Congress; 1862. Public Laws of the Confederate States of America, Passed at the First Session of the First Congress; 1862. Private Laws of the Confederate States of America, Passed at the First Session of the First Congress; 1862.

- Kara E. Kozikowski. Guerrilla Warfare: Hometown heroes and villains, American Battlefield Trust

- Nosworthy, Brent. The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War. Carroll & Graf, 2003.

- Taran, Nicholas. United States Army counter partisan operations in northern Virginia during the American Civil War. Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Command and General Staff College, 2016.

Further reading

- Johnson, Adam Rankin, and William J. Davis. The Partisan Rangers of the Confederate States Army. Louisville, Ky.: G. G. Fetter Company, 1904.

- Raiford, Neil Hunter. "The 4th North Carolina Cavalry in the Civil War." McFarland & Company, 2003, p. 5. ISBN 0-7864-1468-5

- Mackey, Robert R. "The UnCivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865." University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8061-3736-0.

- Inc Ebrary. "Modern Insurgencies and Counter-Insurgencies: Guerrillas and their Opponents Since 1750". Routledge (UK), 2001. ISBN 0-415-23934-6

- McKnight, Brian D., and Barton A. Myers, eds. "The Guerrilla Hunters: Irregular Conflicts During the Civil War," 2017.