Turning point of the American Civil War

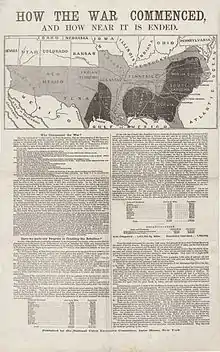

There is widespread disagreement among historians about the turning point of the American Civil War. A turning point in this context is an event that occurred during the conflict after which most modern scholars would agree that the eventual outcome was inevitable. While the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 is the event most widely cited as the military climax of the American Civil War (often in combination with the Siege of Vicksburg, which concluded a day later), there were several other decisive battles and events throughout the war which have been proposed as turning points. These events are presented here in chronological order. Only the positive arguments for each are given.

At the time of an event, the fog of war often makes it impossible to recognize all of the implications of any specific outcome. Only hindsight can fully reveal the endpoint and all of the developments that led up to it. For this reason, contemporary observers may lack confidence in predicting a turning point. Many of the turning points of the Civil War cited here would not have been recognized as such at the time.

Confederate victory at Bull Run (July 1861)

The First Battle of Bull Run, on July 21, 1861, was the first major land battle of the war. Until this time, the North was generally confident about its prospects for quickly crushing the rebellion with an easy, direct strike against the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. The embarrassing rout of Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell's army during the battle made clear the fallacy of this viewpoint. Many Northerners were shocked and realized that the war was going to be much lengthier and bloodier than they had anticipated. It steeled their determination. If Confederates had hoped before this that they could sap Northern willpower and quietly slip away from the Union with a minor military investment, their victory at Bull Run, ironically, destroyed those hopes.[1] Lincoln immediately signed legislation that increased the Union Army by 500,000 men and allowed for their terms of service to last the duration of the war. Congress quickly passed the Confiscation Act of 1861, which declared that if a slave holder used his slaves to support the Confederacy he would forfeit his right to them. While the status of the slaves was unclear at the time (they were held as war contraband until the Emancipation Proclamation), this was the first legislative step toward defining the war as a matter of ending slavery.

.png.webp)

Confederate invasion of Kentucky (September 1861)

By mid-1861, eleven states had seceded, but four more slave-owning "border states" remained in the Union—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. Kentucky was considered the most at risk; the state legislature had declared neutrality in the dispute, which was seen as a moderately pro-Confederate stance. The loss of Kentucky might have been catastrophic because of its control of the strategic Tennessee and Ohio rivers and its position from which the vital state of Ohio could be invaded. Lincoln wrote, "I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game."

On September 3, 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk extended his defensive line north from Tennessee when Gideon Pillow occupied Columbus, Kentucky (in response to Ulysses S. Grant's occupation of Belmont, Missouri, directly across the Mississippi River). Polk followed this by moving through the Cumberland Gap and occupying parts of southeastern Kentucky. This violation of state neutrality enraged many of its citizens; the state legislature, overriding the veto of the governor, requested assistance from the federal government. Kentucky was never again a safe area of operation for Confederate forces. Ironically, Polk's actions were not directed by the Confederate government. Thus, almost by accident, the Confederacy was placed at an enormous strategic disadvantage. Indeed, the early Union successes in the Western Theater (the locale of all their successful large-scale non-naval initiatives until 1864) can be directly tied to Polk's blunder.

Union capture of Forts Henry and Donelson (February 1862)

The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, and the Confederate surrender at the latter, were the first significant Union victories during the war and the start of a mostly successful campaign in the Western Theater. Ulysses S. Grant completed both actions by February 16, 1862, and by doing so, opened the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers as Union supply lines and avenues of invasion to Tennessee, Mississippi, and eventually Georgia. The loss of control of these rivers was a significant strategic defeat for the Confederacy. This was the start of offensive actions by Grant that, with the sole exception of the Battle of Shiloh, would continue for the rest of the war.

Albert Sidney Johnston's death (April 1862)

Albert Sidney Johnston was considered one of the best generals serving in the Western Theater. By 1862, he commanded all Confederate forces between the Cumberland Gap and Arkansas. Before the battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, Johnston had advocated improving the forts' structures as well as deploying additional troops and arms to more adequately defend them. The Confederate government failed to meet these recommendations. Ulysses S. Grant captured the forts in February 1862 and launched a full-scale invasion of Tennessee. The fall of these forts was inaccurately blamed on Johnston, but he continued to serve.

In March 1862, Johnston organized the Army of Mississippi with P.G.T. Beauregard. He launched his attack at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. Johnston's plan was to drive the Union army from its landing point on the Tennessee River into the surrounding swamps. He assigned Beauregard to coordinate the attack. Beauregard disagreed with his strategy and instead planned to drive the enemy back toward the river. He in turn directed reconnaissance at this plan, resulting in the ultimate failure to pinpoint Grant's army. On the first day of battle, Johnston personally led the attack on the enemy. He was a victim of friendly fire, receiving a hit in the knee which severed his popliteal artery. Johnston died within an hour. His death resulted in critical reassignments of his command to less talented generals who failed to repair the virtually doomed Western Theater.

Union capture of New Orleans (April 1862)

Early in the war, Confederate strategists believed the primary threat to New Orleans would come from the north, and made their defensive preparations accordingly. As forces under Grant made gains in the Western Theater, much of the military equipment and manpower in the city's vicinity was sent up the Mississippi River in an attempt to stem the victorious Union tide.[2] When Flag Officer David Farragut was able to force the Union Navy's West Gulf Blockading Squadron past the Confederacy's only two forts below the city in the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, New Orleans had no means to oppose capture. Thus the port, by far the largest Confederate city, fell undamaged into Union hands, tightening its grip on the Mississippi River and fulfilling a key element of the Anaconda Plan for the South's defeat. Although the occupation under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler was detested, he was astute enough to build a base of political support among the poorer classes and create an extensive intelligence and counterespionage capability, nullifying the threat of insurrection. The Confederacy's loss of its greatest port had significant diplomatic consequences. Confederate agents abroad were generally received more coolly, if at all, after news of the city's capture reached London and Paris.

Union victory at Battle of Antietam (September 1862)

The Battle of Antietam, fought September 17, 1862, was the bloodiest single day of conflict in American military history. But it also had two strategic consequences. Although considered a tactical draw between the Army of the Potomac and the much smaller Army of Northern Virginia, it marked the end of Robert E. Lee's invasion of the North. One of his goals was to entice the slave-holding state of Maryland to join the Confederacy, or at least recruit soldiers there. He failed in that objective; he also failed in marshaling Northern fears and opinions to pressure a settlement to the war.[3]

But more strategically, George B. McClellan's victory was just convincing enough that President Lincoln used it as justification for announcing his Emancipation Proclamation. He had been counseled by his cabinet to keep this action confidential until a Union battlefield victory could be announced, lest it appear to be an act of desperation. Along with its immense effect on American history and race relations, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively prevented the British Empire from recognizing the Confederacy as a legitimate government. The British public had strong anti-slavery beliefs and would not have tolerated joining the pro-slavery side of a fight where slavery was now a prominent issue.[4] This greatly diminished the Confederacy's hopes of surviving a lengthy war against the North's suffocating naval blockade. Support from France was still a possibility, but it never came to pass. Antietam and two other coincident failed actions—Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky (sometimes called the "high-water mark of the Confederacy in the Western Theater"[5]) and Earl Van Dorn's advance against Corinth, Mississippi—represented the Confederacy's only attempts at coordinated strategic offensives in multiple theaters of war.[6]

Stonewall Jackson's death (May 1863)

After winning the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Army of Northern Virginia lost Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson to pneumonia following a friendly fire accident. His death was a blow to the morale of the Confederate army, as he was one of its most popular and successful commanders. Two months later, Robert E. Lee had no general with Jackson's audacity available at the Battle of Gettysburg. Many historians argue that Jackson might have succeeded in seizing key battlefield positions (such as Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill at the end of day one) that his replacements were unable or unwilling to take.[7] Lee himself shared this belief and is said to have told his subordinate generals on different occasions that they should have acted like Jackson would have.[8]

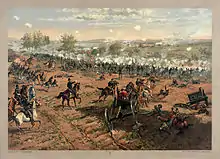

Union capture of Vicksburg and victory at Gettysburg (July 1863)

On July 4, 1863, the most important Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River at Vicksburg, Mississippi surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant. The previous day, Maj. Gen. George Meade had decisively defeated Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. These nearly simultaneous battles are the events most often cited as the ultimate turning points of the entire war.[9]

The loss of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two, denying it any further movement along or across the Mississippi River and preventing supplies from Texas and Arkansas that might sustain the war effort from passing east. As President Lincoln had stated, "See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.... We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy and they can defy us from Vicksburg."

Gettysburg was the first major defeat suffered by Lee. The three-day battle witnessed the Union Army of the Potomac decisively repel his second invasion of the North and inflicted serious casualties on his Army of Northern Virginia. In fact, the National Park Service marks the point at which Pickett's Charge collapsed, a copse of trees on Cemetery Ridge, as the high-water mark of the Confederacy. From this point onward, Lee attempted no more strategic offensives. Although two more years of fighting and a new, more aggressive general-in-chief (Grant) was required to fully subdue the rebellion, the eventual end at Appomattox Court House in 1865 seems inevitable in hindsight.

While Gettysburg was seen by military and civilian observers at the time as a great battle, those in the North had little idea that two more bloody years would be required to finish the war. Lincoln was distraught at Meade's failure to intercept Lee's retreat, believing that to have done so would have ended the conflict.[10] Southern morale was seriously affected by the twin setbacks of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, as they perceived that "the coil was tightening around us".[11]

Some economic historians have pointed to the fact that after the defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the market for Confederate war bonds dropped precipitously. "… European investors gave the Confederacy approximately a 42 percent chance of victory prior to the battle of Gettysburg/Vicksburg. News of the severity of the two rebel defeats led to a sell-off in Confederate bonds. By the end of 1863, the probability of a Southern victory fell to about 15 percent."[12]

Union victory in the Chattanooga Campaign (November 1863)

Military historian J.F.C. Fuller contended that Grant's defeat of Braxton Bragg's army at Chattanooga, Tennessee was the turning point of the war because it reduced the Confederacy to the Atlantic coast and opened the way for William T. Sherman's Atlanta Campaign and March to the Sea.[14][15]

Grant's appointment as Union general-in-chief (March 1864)

Following the victory at Chattanooga, Grant was appointed general-in-chief of all Union armies on March 12, 1864. Leaving Sherman in command of forces in the Western Theater, he moved his headquarters east to Virginia. Previous Union commanders in the critical Eastern Theater had not mounted effective campaigns, or successful pursuits of Confederate forces after gaining rare victories. Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the Confederacy from multiple directions: against Lee and the Confederate capital, Richmond; in the Shenandoah Valley; against Johnston and Atlanta; against railroad supply lines in western Virginia; and against the port of Mobile. In May, Grant launched the Overland Campaign towards Richmond, an attritional campaign that took full advantage of the North's edge in population and resources. Although he suffered a tactical reverse in his first encounter with Lee in the Battle of the Wilderness, Grant pressed forward, putting the Confederates under an unremitting pressure that was maintained until the fall of their capital and the surrender of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Union capture of Atlanta (September 1864)

Some contend that Sherman's successful siege of Atlanta was the turning point, since the heavily fortified city was the most critical remaining stronghold in the South.[16] The capture of Atlanta, following a tedious and frustrating campaign, lifted the spirits of Unionists and came just in time to build the popular support necessary to re-elect Lincoln, in addition to its military result of crippling transportation in the heart of the Confederacy and nearly destroying the city.

Lincoln's reelection (November 1864)

The reelection of Abraham Lincoln in 1864 is beyond the final point at which a positive conclusion for the Confederacy could have been contemplated. His opponent, former general George B. McClellan, ran on a Democratic Party platform that favored a negotiated settlement with the Confederacy. Although McClellan disavowed this platform, the South would have likely seen his election as a strategic victory. Thus, Lincoln's success may have further emboldened belief, on both sides, in the notion that the war would eventually end with the Union's original ambition achieved.

See also

Notes

- Rawley, pp. 49–67.

- McPherson, pp. 418–19; Foote, vol. 1, p. 361

- Rawley, pp. 97–114.

- Rawley, p. 142.

- McPherson (p. 858) considers the Union victory at Perryville in combination with that at Antietam to be the second of the war's four major turning points, one in which the possibility of an imminent Southern victory was quashed.

- Rawley, p. 101.

- "May 2, 1863: Stonewall Jackson Shot by His Own Men at Chancellorsville". learning.blogs.nytimes.com. New York Times. 2012-05-02. Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- Martin, pp. 563–65; Foote, vol. 2, p. 596

- McPherson, p. 665

- Rawley, pp. 156–57; Foote, vol. 2, pp. 626–27; McPherson, pp. 666–67.

- Rawley, p. 145; Rawley, p. 163; Foote, vol. 2, pp. 641–42; McPherson, p. 665.

- Weidenmier, M. D.; Oosterlinck, K. (November 2007). "Victory or Repudiation? The Probability of the Southern Confederacy Winning the Civil War". NBER Working Paper Series (13567). doi:10.3386/w13567.

- McPherson, p. 677, p. 680

- Fuller was inconsistent in naming turning points. In his 1929 work The Generalship of Ulysses S. Grant, he cited three ( p. 46): First Bull Run, which resulted in establishment of unity of command in the Union army; Fort Donelson, after which he considered Vicksburg and Atlanta (and presumably Chattanooga) to be inevitable; and the fall of Wilmington, which he claimed led directly to Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House.

- McPherson (p. 858) lumps this Union victory together with the earlier ones at Vicksburg and Gettysburg as the war's third major turning point.

- McPherson (p. 858) considers the Union capture of Atlanta and its coincident victory in the Shenandoah Valley to be the last of the war's four major turning points, one which overcame the demoralizing effects of the appalling casualties of the Overland Campaign and the apparent stalemate at Petersburg to ensure continued Northern support for pursuit of ultimate victory.

References

- Foote, Shelby (2011). The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 1: Fort Sumter to Perryville. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-74467-8. OCLC 712783750.

- Foote, Shelby (2011). The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-74468-5. OCLC 712783750.

- Foote, Shelby (2011). The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 3: Red River to Appomattox. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-74469-2. OCLC 712783750.

- Fuller, Maj. Gen. J. F. C. (1929). The Generalship of Ulysses S. Grant. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80450-2. OCLC 1523705.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7. OCLC 15550774.

- Martin, David G. (2003). Gettysburg, July 1. Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81240-8. OCLC 44965867.

- Rawley, James A. (1966). Turning Points of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8935-2. OCLC 44957745.

- Unpublished remarks by Gary Gallagher and James M. McPherson, 2005 University of Virginia seminar: Great Battles and Turning Points of the Civil War.