Cimoliopterus

Cimoliopterus is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Cretaceous of England, United Kingdom and Texas, United States.[1]

| Cimoliopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype snout tip of C. cuvieri (specimen NHMUK PV 39409) shown from the right side and below | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Lanceodontia |

| Clade: | †Ornithocheirae |

| Clade: | †Targaryendraconia |

| Family: | †Cimoliopteridae |

| Genus: | †Cimoliopterus Rodrigues & Kellner, 2013 |

| Type species | |

| †Pterodactylus cuvieri Bowerbank, 1851 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Synonyms of C. cuvieri

| |

The type species, Cimoliopterus cuvieri, was previously considered parts of several different genera depending on author, but received its own genus in 2013.[2]

History of discovery

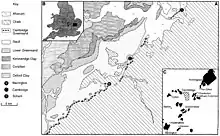

In 1851, the British naturalist James Scott Bowerbank described a large pterosaur snout he had obtained, which was found in a pit in the Chalk Formation at Burham, Kent, in South East England. Pterosaur fossils had earlier been discovered in the same pit, including the front part of some jaws Bowerbank had used as the basis for the species Pterodactylus giganteus in 1846, as well as other bones. Based on the new snout, Bowebank named the new species Pterodactylus cuvieri; the specific name honours the French palaeontologist Georges Cuvier. He believed some large bones in three other collections may either have belonged to the same species, to P. giganteus, or to a third possible species.[3]

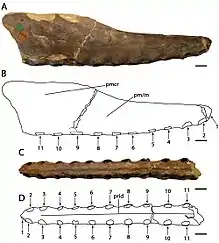

The holotype snout, today catalogued as NHMUK PV 39409 at the Natural History Museum in London, consists of the front 18 cm (7 in) of a partial upper jaw, including a crest located on the premaxilla, the frontmost bone of the upper jaw. Eleven alveoli (tooth sockets) are preserved on each side. It was originally reported to preserve a single tooth in the right first alveolus (tooth socket at the front of the snout), but this had disappeared when the holotype was examined in 2007 and 2009. Two complete teeth were also originally reported to be preserved in the same block of chalk as the snout.[2][4][3]

In 1869, Harry Govier Seeley renamed the species into Ptenodactylus cuvieri,[5] at the same time disclaiming the name which makes it invalid by modern standards. In 1870, Seeley had realised that the generic name Ptenodactylus had been preoccupied and renamed the species into Ornithocheirus cuvieri.[6] In 1874, Richard Owen renamed it into Coloborhynchus cuvieri;[7] in 2001, David Unwin considered it as a species of Anhanguera: A. cuvieri.[8]

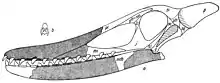

In 1919 and 1922, the Austrian naturalist Gustav von Arthaber lamented that the scientific literature had accepted the many Ornithocheirus names that had only been mentioned in a catalogue made by Seeley for the benefit of students. In his opinion names were worthless without an illustration of the specimens they were based on, or better still a complete restoration of the relevant skeleton. For this reason, he provided a drawing of the skull of Ornithocheirus cuvieri, one of the few species for which the known jaw material proved its validity.[9]

In 2013, Taissa Rodrigues and Alexander Wilhelm Armin Kellner created a separate genus: Cimoliopterus. The generic name combines Κιμωλία, Kimolia, the white clay of the island Kimolos (kimolia means "chalk" in New Greek) with a Latinised Greek πτερόν, pteron, "wing". The type species remains Pterodactylus cuvieri, the resulting combinatio nova, new combination name, is Cimiliopterus cuvieri.[2]

Ornithocheirus brachyrhinus Seeley 1870 and Pterodactylus fittoni Owen 1859 share several features with C. cuvieri, and it can therefore not be excluded that they are the same taxon. However, they are too incomplete to be definitely referred to C. cuvieri, so were by Rodrigues and Kellner considered nomina dubia.[2]

In 2015, a new species was described: Cimoliopterus dunni, which was discovered in the Britton Formation on the north-central Texas, United States, and its fossil remains date to the Cenomanian stage, of the early Late Cretaceous. The holotype specimen consists in a partial rostrum with the 26 preserved alveoli and bears a thin premaxillary crest that begins over the fourth alveoli, the tip of the snout is blunt and the rostrum have an angle of 45° respect to the anterior part of the palate. This find extends the distribution of the genus to North America and shows that the pterosaur faunas from Europe and North America still had contact during the middle Cretaceous. The phylogenetic analysis included in the description of this species indicates that Cimoliopterus is a basal pteranodontoid closely related with Aetodactylus, which has also been found in Cenomanian strata from Texas.[1]

Description

Bowerbank, extrapolating from the remains of P. giganteus, estimated a wingspan for P. cuvieri of about 5.029 metres (16.50 ft), making it the largest flying animal, extinct or extant, known in 1851.[3] This claim at the time was met with considerable scepticism, though today, larger pterosaurs are known to have existed.[10] Currently, the only known remains of Cimoliopterus are fragments of the skull.[11]

The holotype of the species Cimoliopterus cuvieri consists of an incomplete upper jaw, which is narrow in the preserved portion. The crest of C. cuvieri is, on the premaxilla (the frontmost cranial bone), placed far back, at the level of the seventh tooth pair. However, it begins before the nasoantorbital fenestra, which is the skull opening where the antorbital fenestra and the bony nostril are combined. In the anterior (front) part of the jaw of C. cuvieri there are three alveoli (tooth sockets) per 3 centimetres (1.2 in) of jaw margin, and two alveoli per 3 centimetres (1.2 in) of jaw margin at the back of the jaw. The front portion of the ridge on the midline of the palate (upper part of the mouth) reaches the level of the third tooth pair, the palate itself is curved upwards and there is no expansion of the jaw at the front. The second tooth pair is about the same size as the third, and both of them are larger than the fourth tooth pair. To the rear part of the jaw, the distance between the teeth gradually increases.[2]

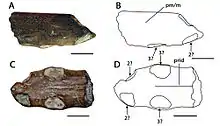

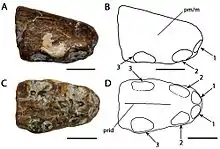

The holotype of C. dunni, SMU 76892, is composed of 18.5 centimetres (7.3 in) of the anterior portion of the rostrum (snout), and comprises both the premaxilla and the maxilla, which appear to have been broken until the thirteeth pair of alveoli. Both C. dunni and C. cuvieri do not show the pronounced lateral expansion of the rostral tip, this feature is a key characteristic of a lot of other toothed pteranodontoids. In both species, this lateral rostral expansion is developed so weakly that it had even been considered to be absent once, and in comparison to the pronounced rostral expansions of other pterosaurs such as those of Anhanguera, Coloborhynchus, and Ornithocheirus, the rostral expansions seen in both C. cuvieri and C. dunni bear so little resemblance to them.[1] This is also why C. cuvieri can be distinguished from the three former genera; it has a low rostrum compared to the genus Ornithocheirus, it also possess a forward-facing first pair of alveoli, unlike Ornithocheirus; C. cuvieri can furthermore be distinguished from the genus Anhanguera because it does not possess an anterior expansion of the rostrum, as mentioned before, which is seen in members of the family Anhangueridae, it also does not have the fourth and fifth alveoli at a smaller size than the third and sixth, which is a key feature in Anhanguera. Due to the more posteriorly positioned premaxillary crest of Cimoliopterus cuvieri, unlike the premaxillary crests seen in anhanguerids, it may perhaps indicate that the crests that C. cuvieri bore had evolved in a separate way.[2][11]

In C. dunni, the premaxillary crest begins just above the fourth alveoli, and it slightly curves upward, this forms a front edge that is concave. The upper edge of the crest seems to descend moderately just before a broken portion, this suggests that the premaxillary crest of C. dunni was, in a lateral view, symmetrical. Supposing that the pterosaur's crest was symmetrical in shape, the complete crest of it would have had a length that was approximately 15 to 16 centimetres (5.9 to 6.3 in). The maximum height of the premaxillary crest of C. dunni is 38 millimetres (1.5 in), the region of the crest where this height is reached is located above the ninth and tenth alveoli. The cortical bone (the hard outer layer of bones) is well-preserved in C. dunni, however, on the left side of the crest, the conjoinment between premaxilla and maxilla is not visible, and on the right side there are several regions where cortical bone is either damaged or missing.[1]

An upward angle of 8 degrees relative to the flat area of the posterior palate can be assumed based on the anterior portion of the palate being dorsally reflected, and an inflection point (the point where a curve changes from convex to concave) close to the level of the eighth alveoli can also be seen. At less than 1 millimetre (0.039 in) high, a narrow palatal ridge extends anteriorly from the broken portion on posterior end of the premaxillary crest. In palatal view of the palate, the anterior end of the rostrum of C. dunni posteriorly expands to a maximum width of 1.6 centimetres (0.63 in) above the third alveoli, narrowing to a minimum width of 1.5 centimetres (0.59 in) at the level of the fourth alveoli. The width of the rostrum continues to increase afterwards, until it reaches a maximum of 1.8 to 1.9 centimetres (0.71 to 0.75 in) at the broken part of the posterior edge of the crest. The spaces between the alveoli of C. dunni gradually increase backward along the row of teeth of the pterosaur, the minimum between the spaces measuring 1.6 millimetres (0.063 in), and the maximum measuring 11.5 millimetres (0.45 in). In total, there are thirteen pairs of alveoli, this is indicates a minimum of twenty-six teeth in the upper jaw.[1]

Classification

Cimoliopterus was by Rodrigues and Kellner (and Myers in 2015) assigned to the Pteranodontoidea, in an uncertain position (incertae sedis). Cladistic analyses indicated a position in the evolutionary tree above Istiodactylus but below a polytomy formed by more derived forms.[2]

In 2018, Jacobs et al. performed a phylogenetic analysis where they placed Cimoliopterus within the family Ornithocheiridae, as the sister taxon of Camposipterus. They published their analysis in 2019.[13] In the same year however, Pêgas et al. reassigned Cimoliopterus to the clade Targaryendraconia, more specifically to its own family, the Cimoliopteridae, and sister taxon to both Aetodactylus and Camposipterus.[11]

|

Topology 1: Jacobs et al. (2019).[13]

|

Topology 2: Pêgas et al. (2019).[11]

|

Palaeoenvironment

The holotype of C. cuvieri, NHMUK PV 39409, had been found in the Grey Chalk Subgroup dating from the Cenomanian-Turonian.[2][1]

References

- Myers, Timothy S. (2015). "First North American occurrence of the toothed pteranodontoid pterosaur Cimoliopterus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35: e1014904. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1014904.

- Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys. 308: 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139. PMID 23794925.

- Bowerbank, J. S. (1851). "On the pterodactyles of the Chalk Formation". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 19: 14–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1851.tb01125.x.

- Owen, R. (1849–1884). A History of British Fossil Reptiles. 1. London: Cassell & Company Limited. pp. 242–244. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7529.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Seeley, H.G., 1869, Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Deighton, Bell and Co., Cambridge, xxiii + 143 pp

- Seeley, H.G., 1870, The Ornithosauria: an elementary study of the bones of pterodactyls, made from fossil remains found in the Cambridge Upper Greensand, and arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Deighton, Bell, and Co., Cambridge, xii + 135 pp

- Owen, R. 1874, Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic Formations. Palaeontographical Society, London, 14 pp

- Unwin, D. M. (2001). "An overview of the pterosaur assemblage from the Cambridge Greensand (Cretaceous) of Eastern England". Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe. 4: 189–221. doi:10.1002/mmng.4860040112.

- Von Arthaber, G. (1922). "Über Entwicklung, Ausbildung und Absterben der Flugsaurier". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 4: 1–47.

- Witton, M.P., Martill, D.M. and Loveridge, R.F. (2010). "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity". Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 31: 79–81.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Pêgas, R.V.; Holgado, B.; Leal, M.E.C. (2019). "On Targaryendraco wiedenrothi gen. nov. (Pterodactyloidea, Pteranodontoidea, Lanceodontia) and recognition of a new cosmopolitan lineage of Cretaceous toothed pterodactyloids". Historical Biology. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1690482.

- Von Arthaber, G. (1919). "Studien über Flugsaurier auf Grund der Bearbeitung des Wiener Exemplars von Dorygnathus banthensis Theod Sp". Denkschriften der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse. 97: 391–464.

- Jacobs, M.L., Martill, D.M., Ibrahim, N., Longrich, N. (2019). "A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.10.018.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)