Dsungaripteridae

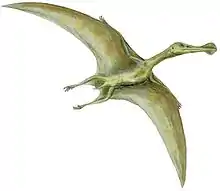

Dsungaripteridae is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea.[4] They were robust pterosaurs with good terrestrial abilities and flight honed for inland settings.[5]

| Dsungaripterids | |

|---|---|

| |

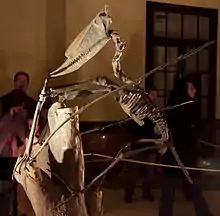

| Restored skeleton of Dsungaripterus weii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Dsungaripteromorpha |

| Family: | †Dsungaripteridae Young, 1964 |

| Type species | |

| †Dsungaripterus weii Young, 1964 | |

| Genera | |

Classification

In 1964 Young created a family to place the recently found Chinese genus Dsungaripterus. Later on, also Noripterus (then now with the name "Phobetor" which was already occupied, therefore the quotation marks) were assigned to the family.

In 2003, Alexander Kellner gave the exact definition as a clade:[6] the group was composed out of the latest common ancestor of Dsungaripterus, Noripterus and “Phobetor”, and all its descendants. As synapomorphies he gave the next six characteristics: a relatively small eye-socket, which is placed high up the skull; an opening below the eye-socket; a high ridge across the snout, which starts in front of the nasal opening and ends behind the eye-sockets; the maxilla reaches out down- and backwards; the absence of teeth in the first part of the jaws; the teeth in the back of the upper jaw are the biggest; the teeth have a wide oval basis. Kellner pointed out all members of the group, except for Dsungaripterus itself, were known from fragmentary remains, so only the last characteristic could be established for sure in all members.[6]

Also Domeykodactylus and Lonchognathosaurus were assigned to the group. They are medium-sized forms, adapted to eating hard-shelled creatures, which they grind with their flat teeth.

In the same year, David Unwin gave a slightly different definition: the last common ancestor of Dsungaripterus weii and Noripterus complicidens, and all its descendants.[7]

The known Dsungaripteridae range from the Late Jurassic to the Cretaceous (Hauterivian). The group belongs to the Dsungaripteroidea sensu Unwin and is presumably relatively closely related to the Azhdarchoidea. According to Unwin, Germanodactylus is the sister taxon to the group, but his analyses have this outcome as the only ones. According to an analysis by Brian Andres from 2008, the Dsungaripteridae are closely related to the Tapejaridae, what would actually make them members of the Azhdarchoidea.[8]

The earliest known fossils attributed to this group are from the Early Cretaceous of Chile, belonging to the species Domeykodactylus ceciliae.[9] The last known dsungaripteroid species is Lonchognathosaurus acutirostris, from the Albian-age Lower Cretaceous Lianmuqin Formation of Xinjiang, China, about 112 million years ago.[10]

Recent examinations of Dsungaripterus' palate confirm an azhdarchoid interpretation.[11]

Family tree

Below is a cladogram showing the results of a phylogenetic analysis presented by Andres and colleagues in 2014. They recovered Dsungaripteridae within the Dsungaripteromorpha (a subgroup within the Azhdarchoidea), sister taxon to the subfamily Thalassodrominae. The found Dsungaripteridae to consist of two subfamilies called Dsungaripterinae and Noripterinae (which consists only of Noripterus species). Their cladogram is shown below.[12]

| Dsungaripteromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2019, a different topology, this time by Kellner and colleagues, was published. In this study, Dsungaripteridae was recovered outside the Azhdarchoidea, within the larger group Tapejaroidea. The cladogram of the analysis is shown below.[13]

| Tapejaroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Unwin, David M.; Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter (1999). "On a pterosaur jaw from the Upper Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)". Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe. 2: 121–134.

- Jaime A. Headden and Hebert B.N. Campos (2014). "An unusual edentulous pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation of Brazil". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. in press (7): 1–12. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.904302.

- Bonaparte, J.F., and Sanchez, T.M. (1975). Restos de un pterosaurio Puntanipterus globosus de la formación La Cruz provincia San Luis, Argentina. Actas Primo Congresso Argentino de Paleontologia e Biostratigraphica 2:105-113. [Spanish]

- Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0691150611.

- Kellner, A.W.A., 2003. Pterosaur phylogeny and comments on the evolutionary history of the AN group. In: Buffetaut, E., Mazin, J.M. (Eds.), Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 217, 105–137.

- Unwin, D. M., (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs." Pp. 139-190. in Buffetaut, E. & Mazin, J.-M., (eds.) (2003). Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 217, London, 1-347.

- Andres, B.; Ji, Q. (2008). "A new pterosaur from the Liaoning Province of China, the phylogeny of the Pterodactyloidea, and convergence in their cervical vertebrae". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 453–469. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00761.x.

- D. M. Martill, E. Frey, G. C. Diaz and C. M. Bell. 2000. Reinterpretation of a Chilean pterosaur and the occurrence of Dsungaripteridae in South America. Geological Magazine 137(1):19-25.

- Maisch, M.W.; Matzke, A.T.; Sun, Ge (2004). "A new dsungaripteroid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of the southern Junggar Basin, north-west China". Cretaceous Research. 25 (5): 625–634. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2004.06.002.

- Chen, He; Jiang, Shunxing; Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Cheng, Xin; Zhang, Xinjun; Qiu, Rui; Li, Yang; Wang, Xiaolin (April 1, 2020). "New anatomical information on Dsungaripterus weii Young, 1964 with focus on the palatal region". PeerJ. 8: e8741. doi:10.7717/peerj.8741 – via peerj.com.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Weinschütz, Luiz C.; Holgado, Borja; Bantim, Renan A. M.; Sayão, Juliana M. (19 August 2019). "A new toothless pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from Southern Brazil with insights into the paleoecology of a Cretaceous desert". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 91 (suppl 2): e20190768. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201920190768. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 31432888.