Noripterus

Noripterus (meaning "lake wing" from Mongolian nuur, "lake" and Greek pteron, "wing") is a genus of dsungaripterid pterodactyloid pterosaur from Lower Cretaceous-age Lianmuqin Formation in the Junggar Basin of Xinjiang, China. It was first named by Yang Zhongjian (also known as C.C. Young in older sources) in 1973. Additional fossil remains have been recovered from Tsagaantsav Svita, Mongolia.

| Noripterus | |

|---|---|

| |

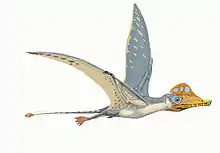

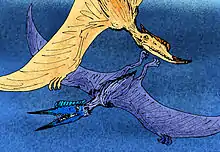

| Artist's impression, with Dsungaripterus weii (top) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Dsungaripteridae |

| Genus: | †Noripterus Young, 1973 |

| Type species | |

| †Noripterus complicidens Young, 1973 | |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The first, holotype specimen of Noripterus (IVPP V.4062, type locality IVPP 64045) preserved the front part of the skull and lower jaws, vertebrae, and partial limbs and pelvis. Noripterus was quite similar to the contemporaneous Dsungaripterus, though it was estimated to be a third shorter. It has long narrow neck vertebrae and, like Dsungaripterus, a crest and no teeth in the front of the lower jaw. The teeth that are present are well-developed and spaced fairly far apart. The sharp snout is straight and not pointed upwards as with Dsungaripterus.[1]

Classification

Because of its similarity to Dsungaripterus, Noripterus has been assigned to the family Dsungaripteridae.[2]

The genus Phobetor, was in 1982 originally described by Natasha Bakhurina as a species of Dsungaripterus (D. parvus), based on a single lower leg bone, PIN 3953. The discovery of more remains later, among which an almost complete skull, GIN 100/31, was reason for Bakhurina to name D. parvus in 1986 as a separate genus, and the species name became Phobetor parvus. However, the genus name Phobetor was already being used as a junior synonym of a species of sculpin, namely, the arctic staghorn sculpin, Gymnocanthus tricuspis (synonym "Phobetor tricuspis" Krøyer, 1844) and thus unavailable. In 2009, Lü and colleagues re-examined much of the known dsungaripterid fossil material, and found that "Phobetor" was indistinguishable from Noripterus, causing them to refer to it as a junior synonym.[3]

Assigning the "Phobetor" material to Noripterus increases the known size of the latter as it indicates a maximum wingspan of 4 metres (13.1 ft).[4]

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic placement of Noripterus within Neoazhdarchia from Andres and Myers (2013).[5]

| Neoazhdarchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology and ecology

Dsungaripterids like Noripterus are interpreted as adapted for feeding on shellfish or other hard foodstuffs, with long narrow toothless beak tips for probing and picking up suitable prey, and robust teeth farther back for cracking shells. The skulls of these animals are more robust than those of other pterosaurs, as well as their limbs and vertebrae.[6]

Noripterus lived in the same time and place as the larger Dsungaripterus, in formations that indicate the presence of extensive inland lake systems. Because Noripterus had a more lightly built skull with weaker, more slender teeth than its larger contemporary, it is likely that the two pterosaurs occupied separate ecological niches.[3]

Like most dsungaripteroids, Noripterus was well adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle, bearing thick bone walls and stouty bodily proportions.[7]

References

- Yang, Zhongjian (1973). "Reports of Paleontological Expedition to Sinkiang (II): Pterosaurian Fauna from Wuerho, Sinkiang". Memoirs of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Academia Sinica (in Chinese). 11: 18–35.

- Unwin, David M. (2003) "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs", in Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs, 139-190.

- Lü, J., Azuma, Y., Dong, Z., Barsbold, R., Kobayashi, Y., and Lee, Y.-N. (2009), "New material of dsungaripterid pterosaurs (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from western Mongolia and its palaeoecological implications." Geological Magazine, 146(5): 690-700.

- D.M. Unwin & N.N. Bakhurina (2003), "Pterosaurs from Russia, Middle Asia and Mongolia", p. 426 In: Michael J. Benton e.a. (ed.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia, Cambridge University Press

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-13-146308-0.

- Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0691150611.