Cycnorhamphus

Cycnorhamphus (meaning "swan beak") is a genus of gallodactylid ctenochasmatoid pterosaur from the Late Jurassic period of France and Germany, about 152 million years ago.[1] It is probably synonymous with the genus Gallodactylus.

| Cycnorhamphus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Juvenile specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Ctenochasmatoidea |

| Family: | †Gallodactylidae |

| Genus: | †Cycnorhamphus Seeley, 1870 |

| Species: | †C. suevicus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Cycnorhamphus suevicus (Quenstedt, 1855) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

History

In 1855, a fossil in a plate of shale from the Kimmeridgian, found near Nusplingen in Württemberg, holotype GPIT "Orig. Quenstedt 1855, Taf. 1", was named Pterodactylus suevicus by Friedrich August Quenstedt.[2][3] In 1870, Harry Govier Seeley assigned it to a new genus: Cycnorhamphus.[4] In 1907 however, Felix Plieninger rejected this split, an opinion then shared by most paleontologists. In 1974, Jacques Fabre, when concluding that a new species found and named by him, Gallodactylus canjuersensis, was the same genus as P. suevicus, did not revive Cycnorhamphus, but judged that the latter name was unavailable because of mistakes in the diagnosis by Seeley. P. suevicus thus became Gallodactylus suevicus. However, in 1996, Christopher Bennett pointed out that such mistakes do not invalidate a name and that therefore Cycnorhamphus has priority, making Gallodactylus canjuersensis C. canjuersensis.[3] In 2010 and 2012, Bennett published further re-studies of the fossils, concluding that the differences between the two species could be explained by age, sex or individual variation, and formally synonymized C. canjuersensis and C. suevicus.[5]

Description

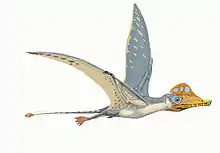

Cycnorhamphus had historically been assumed to have had long jaws with teeth at the very tip, akin to those of Pterodactylus antiquus. However, recent work on a specimen nicknamed "The Painten Pelican"[5] has revealed that the animal possesses a very unusual jaw anatomy, with peg-like teeth at the jaw tips - blunter and stouter in older individuals -, jaw curvatures behind said teeth that form angled arcs away from the biting surface, forming thus an opening, and two poorly understood soft tissue structures occupying this opening from the upper jaw, showing mineralization. The purpose of these adaptations is unknown,[6] but they are more obvious and well developed in adult animals. It has been speculated that the jaws functioned similar to those of openbill storks, allowing the animal to hold hard invertebrates like mollusks and either crush or bisect them.[7]

Classification

As illustrated below, the results of a topology are based on a phylogenetic analysis made by Longrich, Martill, and Andres in 2018. They placed the Cycnorhamphus within the clade Euctenochasmatia, more precisely within the family Gallodactylidae, sister taxon to Normannognathus.[8]

| Archaeopterodactyloidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- F. A. Quenstedt. 1856. Sonst und Jetzt. Populäre Vorträge über Geologie [Other and Now. Popular Lectures on Geology] viii-288

- Bennett, S. Christopher (1996). "On the taxonomic status of Cycnorhamphus and Gallodactylus (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea)". Journal of Paleontology. 70 (2): 335–338.

- H. G. Seeley. 1870. The Ornithosauria: an elementary study of the bones of pterodactyles, made from fossil remains found in the Cambridge Upper Greensand, and arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge, Deighton, Bell & Co, Cambridge

- Bennett, S. C. (2013). "The morphology and taxonomy of the pterosaur Cycnorhamphus". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 267: 23–41. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2012/0295.

- Frey and Tischlinger (2010)

- Witton, Mark P. (2013), Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy

- Longrich, N.R.; Martill, D.M.; Andres, B. (2018). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLoS Biology. 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. PMC 5849296. PMID 29534059.