Darwinopterus

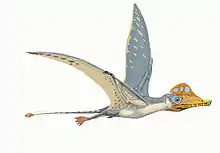

Darwinopterus (meaning "Darwin's wing") is a genus of pterosaur, discovered in China and named after biologist Charles Darwin.[1] Between 30 and 40 fossil specimens have been identified,[2] all collected from the Tiaojishan Formation, which dates to the middle Jurassic period, 160.89–160.25 Ma ago.[3][4] The type species, D. modularis, was described in February 2010.[1] D. modularis was the first known pterosaur to display features of both long-tailed ('rhamphorhynchoid') and short-tailed (pterodactyloid) pterosaurs, and was described as a transitional fossil between the two groups.[5] Two additional species, D. linglongtaensis and D. robustodens, were described from the same fossil beds in December 2010 and June 2011, respectively.[6][7]

| Darwinopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

| D. modularis fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Family: | †Wukongopteridae |

| Genus: | †Darwinopterus Lü et al., 2010 |

| Type species | |

| †Darwinopterus modularis Lü et al., 2010 | |

| Other species | |

| |

Description

Darwinopterus, like its closest relatives, is characterized by its unique combination of basal and derived pterosaurian features. While it had a long tail and other features characteristic of the 'rhamphorhynchoids', it also had distinct pterodactyloid features, such as long vertebrae in the neck and a single skull opening in front of the eyes, the nasoantorbital fenestra (in most 'rhamphorhynchoids', the antorbital fenestra and the nasal opening are separate).[6]

Darwinopterus is distinguished from its close relatives by the greater relative length of the back portion of the skull compared to its jaws, thin nasal bone, and elongated hip bone (illium). The teeth in all species were spaced widely with the longest teeth at the jaw tips. The teeth were spike-like in form, and set into tooth sockets with raised margins. The hand bones were relatively short, even shorter than the femur. The tail was long, with over 20 vertebrae, and was partially stiffened by long, thin bony projections.[7] Unlike other wukongopterids, the head crest found in males was supported by a thin bony extension of the skull, with a serrated top edge. The serrations probably helped anchor an even larger keratin extension.[6]

Specimens of Darwinopterus have been divided into three distinct species, based largely on the size and shape of their teeth. The first, D. modularis, was named by Lü Junchang and colleagues in 2010. D. modularis had an especially elongated back end to the skull, and widely spaced, "spike-like" teeth. D. linglongtaensis was named by Wang Xiaolin and colleagues in later in 2010. It was characterized by a shorter and taller skull and shorter, cone-shaped teeth.[6] In 2011, Lü and another team of scientists described and named D. robustodens, for a new specimen with very robust teeth. Lü and colleagues (2011) suggested that these differences in tooth shape may indicate that each Darwinopterus species occupied a different ecological niche, with the teeth of each becoming specialized for different food sources. The robust teeth of D. robustodens, for example, may have been used to feed on hard-shelled beetles.[7]

Biology

Because Darwinopterus is known from numerous well-preserved specimens including an egg, researchers have been able to deduce various aspects of its biology, including growth patterns and life history, reproduction, and possible variation between sexes.

Sexual variation

The large amount of variation among Darwinopterus specimens has been interpreted as sexual dimorphism. The first Darwinopterus specimen in which sex could be confidently identified was specimen ZMNH M8802 in the collections of the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, nicknamed "Mrs T" (short for "Mrs Pterodactyl"), described by Lü Junchang and colleagues in January 2011. This specimen was preserved with the impression of an egg between its thighs in close association with its pelvis. This specimen had a broad pelvis and lacked any evidence of a crest. The egg was probably expelled from the body during decomposition, and its association with the Darwinopterus individual was used to support the hypothesis of sexual dimorphism.[2]

However, this hypothesis has been criticized. Pterosaur researcher Kevin Padian questioned some of the conclusions drawn by Lü et al., suggesting in a 2011 interview that, in other animals with elaborate display crests (such as ceratopsian dinosaurs), the size and shape of the crests change dramatically with age. He noted that the "Mrs T" specimen may simply have been a sub-adult which had not yet developed a crest (most animals are able to reproduce before they are fully grown).[2] In 2015, Wang e.a. reassigned the "Mrs T" specimen to Kunpengopterus.[8] Furthermore, a rigorous analysis of wukongopterid variation published in 2017 noted that crests among wukongopterids were subject to a large amount of individual variation, and that there was no consistent dimorphism in the pelvic anatomy of crested and uncrested wukongopterid specimens.[9]

Reproduction

The specimen preserved along with an egg (nicknamed "Mrs T"), described by Lü and colleagues in 2011, offers insight into the reproductive strategies of Darwinopterus and pterosaurs in general.[10] Like the eggs of later pterosaurs and modern reptiles,[11] the eggs of Darwinopterus had a parchment-like, soft shell.[2] In modern birds, the eggshell is hardened with calcium, completely shielding the embryo from the outside environment. Soft-shelled eggs are permeable, and allow significant amounts of water to be absorbed into the egg during development. Eggs of this type are more vulnerable to the elements and are typically buried in soil. The eggs of Darwinopterus would have weighed about 6 grams (0.21 oz) when they were laid, but due to moisture intake, they may have doubled in weight by the time of hatching.[2] The eggs were small compared to the size of the mother (the "Mrs T" specimen weighed between 110 grams [3.9 oz] and 220 grams [7.8 oz][2]), also more like modern reptiles than birds. David Unwin, a co-author of the paper, suggested that Darwinopterus probably laid many small eggs at a time and buried them, and that juveniles could fly upon hatching, requiring little to no parental care.[2] These results imply that reproduction in pterosaurs was more like that in modern reptiles and significantly differed from reproduction in birds.[10] However, in 2015, the counterplate of the specimen was reported, IVPP V18403, which showed a single additional egg present in the body, indicating that there were two active ovaries, producing a single egg at a time.[8]

Diet

Darwinopterus, like most wukongopterids, is a terrestrial pterosaur lacking speciations for piscivory; ergo, it was early on recognised to have been a terrestrial form. Originally, it was described as a raptorial hawking carnivore;[1] however, posterior analyses have found no speciations towards aerial predation. Instead, it appears to have been a saltatorial insectivore, hopping around both in the trees and on the ground, akin to some modern songbirds.[12] D. robustidens in particular might have preferred hard-shelled beetles.[7]

Classification

Below is a cladogram following Wang et al. (2017) [13]

| Monofenestrata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Implications

As the name Darwinopterus modularis implies, the researchers who first described this genus saw it as evidence that pterodactyloid pterosaurs evolved from the more primitive 'rhamphorhynchoids' via modular evolution. In other words, rather than a gradual change from one body type to the other, various major aspects of pterodactyloid anatomy arose unsystematically, producing species with distinct combinations of both primitive and advanced features.[1]

References

- Lü J.; Unwin D.M.; Jin X.; Liu Y.; Ji Q. (2010). "Evidence for modular evolution in a long-tailed pterosaur with a pterodactyloid skull". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1680): 383–389. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1603. PMC 2842655. PMID 19828548.

- Hecht, J. (2011). "Did pterosaurs fly out of their eggs?" New Scientist online edition, 20 Jan 2011. Accessed online 21 Jan 2011, https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn20011-did-pterosaurs-fly-out-of-their-eggs.html

- Liu Y.-Q. Kuang H.-W., Jiang X.-J., Peng N., Xu H. & Sun H.-Y. (2012). "Timing of the earliest known feathered dinosaurs and transitional pterosaurs older than the Jehol Biota." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (advance online publication).

- Chu, Z.; He, H.; Ramezani, J.; Bowring, S.A.; Hu, D.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, C.; Guo, J. (2016). "High-precision U–Pb geochronology of the Jurassic Yanliao Biota from Jianchang (western Liaoning Province, China): Age constraints on the rise of feathered dinosaurs and eutherian mammals". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 17 (10): 3983–3992. doi:10.1002/2016GC006529.

- Dell'Amore, C. (2009). "Odd New Pterosaur: 'Darwin's Wing' Fills Evolution Gap." National Geographic News, 13 October 2009. Accessed 14 October 2009.

- Wang, X.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, X.; Meng, X. & Rodrigues, T. (2010). "New long-tailed pterosaurs (Wukongopteridae) from western Liaoning, China" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82 (4): 1045–1062. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652010000400024. PMID 21152776.

- Lü J.; Xu L.; Chang H.; Zhang X. (2011). "A new darwinopterid pterosaur from the Middle Jurassic of western Liaoning, northeastern China and its ecological implications". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 85 (3): 507–514. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2011.00444.x.

- Xiaolin Wang; Kellner Alexander W.A.; Xin Cheng; Shunxing Jiang; Qiang Wang; Sayão Juliana M.; Rordrigues Taissa; Costa Fabiana R.; Ning Li; Xi Meng; Zhonghe Zhou (2015). "Eggshell and Histology Provide Insight on the Life History of a Pterosaur with Two Functional Ovaries". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 87 (3): 1599–1609. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201520150364. PMID 26153915.

- Cheng, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, X.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2017). "Premaxillary crest variation within the Wukongopteridae (Reptilia, Pterosauria) and comments on cranial structures in pterosaurs" (PDF). Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. 89 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201720160742. ISSN 1678-2690. PMID 28198921.

- Lü J.; Unwin D.M.; Deeming D.C.; Jin X.; Liu Y.; Ji Q. (2011). "An egg-adult association, gender, and reproduction in pterosaurs". Science. 331 (6015): 321–324. doi:10.1126/science.1197323. PMID 21252343.

- Ji, Q.; Ji, S.A.; Cheng, Y.N.; You, H.; Lü, J.; Liu, Y. & Yuan, C. (2004). "Palaeontology: pterosaur egg with a leathery shell". Nature. 432 (7017): 572. doi:10.1038/432572a. PMID 15577900.

- Witton, Mark P. (2013), Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy

- Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, G.; Wang, X. (2017). "New evidence from China for the nature of the pterosaur evolutionary transition". Scientific Reports. 7: 42763. doi:10.1038/srep42763. PMC 5311862. PMID 28202936.