Conquest of Chile

The Conquest of Chile is a period in Chilean historiography that starts with the arrival of Pedro de Valdivia to Chile in 1541 and ends with the death of Martín García Óñez de Loyola in the Battle of Curalaba in 1598, and the destruction of the Seven Cities in 1598–1604 in the Araucanía region.

| History of Chile |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

This was the period of Spanish conquest of territories, founding of cities, establishment of the Captaincy General of Chile, and defeats ending its further colonial expansion southwards. The Arauco War continued, and the Spanish were never able to recover their short control in Araucanía south of the Bío Bío River.

Background

Chile at the time of the Spanish arrivals

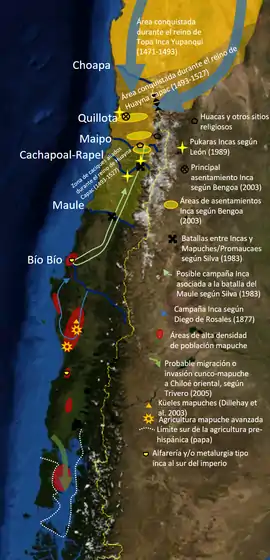

When the Spanish first came to Central Chile the territory had been under Inca rule for less than 60 years. Historian Osvaldo Silva posits the last Inca push towards the south were made as late as in the 1530s.[1] The main settlements of the Inca Empire in Chile lay along the Aconcagua River, Mapocho River, and the Maipo River.[2] Quillota in Aconcagua Valley was likely their foremost settlement.[2] As it appear to be the case in the other borders of the Inca Empire, the southern border was composed of several zones: first, an inner, fully incorporated zone with mitimaes protected by a line of pukaras (fortresses) and then an outer zone with Inca pukaras scattered among allied tribes.[3] This outer zone would according to historian José Bengoa have been located between the Maipo and Maule Rivers.[3]

However the largest indigenous population were the Mapuches living south of the Inca borders in the area spanning from the Itata River to Chiloé Archipelago.[4] The Mapuche population between the Itata River and Reloncaví Sound has been estimated at 705,000–900,000 in the mid-16th century by historian José Bengoa.[5][note 1] Mapuches lived in scattered hamlets, mainly along the great rivers of Southern Chile.[6][7] All major population centres lay at the confluences of rivers.[8] Mapuches preferred to build their houses on hilly terrain or isolated hills rather than on plains and terraces.[7] The Mapuche people represented an unbroken culture dating back to as early as 600 to 500 BC.[9] Yet Mapuches had been influenced over centuries by Central Andean cultures such as Tiwanaku.[10][11] Through their contact with Incan invaders Mapuches would have for the first time met people with state-level organization. Their contact with the Inca gave them a collective awareness distinguishing between them and the invaders and uniting them into loose geopolitical units despite their lack of state organization.[12]

Mapuche territory had an effective system of roads before the Spanish arrival as evidenced by the fast advances of the Spanish conquerors.[13]

First Spaniards in Chile

The first Spanish subjects to enter the territory of what would become Chile were the members of the Magellan expedition that discovered the Straits of Magellan before completing the world's first circumnavigation.

Gonzalo Calvo de Barrientos left Peru for Chile after a quarrel with the Pizarro brothers. The Pizarro brothers had accused Calvo de Barrientos of theft and had him cropped as punishment. Antón Cerrada joined Calvo de Barrientos in his exile.

Diego de Almagro ventured into present-day Bolivia and the Argentine Northwest in 1535. From there he crossed into Chile at the latitudes of Copiapó. Almagros expedition was a failure as he did not find the riches he expected.

Pedro de Valdivia

Expedition to Chile

.jpg.webp)

In April 1539, Francisco Pizarro authorized Pedro de Valdivia as his lieutenant governor with orders to conquer Chile. That did not include monetary aid, which he had to procure on his own. Valdivia did so, in association with the merchant Francisco Martínez Vegaso, captain Alonso de Monroy, and Pedro Sanchez de la Hoz. Sanchez was the longtime secretary to Pizarro, who had returned from Spain with authorization from the king to explore the territories south of the Viceroyalty of Peru to the Strait of Magellan, also granting Valdivia the title of governor over lands taken from the indigenous peoples.

Valdivia came to the Valley of Copiapo and took possession in the name of the King of Spain and named it Nueva Extremadura, for his Spanish homeland of Extremadura. On February 12, 1541, he founded the city of Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura on Huelen hill (present-day Santa Lucia Hill).

Governor

Valdivia had rejected the position and titles due him while Pizarro was alive, as it could have been seen as an act of treason. He accepted the titles after the death of Francisco Pizarro. Pedro de Valdivia was named Governor and Captain-General of the Captaincy General of Chile on June 11, 1541. He was the first Governor of Chile.

Valdivia organized the first distribution of encomiendas and of indigenous peoples among the Spanish immigrants in Santiago. The Chilean region was not as rich in minerals as Peru, so the indigenous peoples were forced to work on construction projects and placer gold mining. The "conquest" was a challenge, with the first attack of Michimalonco in September 1541, burning the new settlement to the ground.

Valdivia authorized Juan Bohon to found the city of La Serena in 1544. The Juan Bautista Pastene expedition ventured to unexplored southern Chile in 1544. Arriving at the Bio-Bio River, started the Arauco War with the Mapuche people. The epic poem La Araucana (1576) by Alonso de Ercilla describes the Spanish viewpoint.

The Spanish won several battles, such as the Andalien battle, and Penco battle in 1550. The victories allowed Valdiva to found cities on the Mapuche homelands, such as Concepcion in 1550, La Imperial, Valdivia, and Villarrica in 1552, and Los Confines in 1553.

Lautaro led the Mapuche rebellion that killed Pedro de Valdivia in the battle of Tucapel in 1553.

Aspects of the Spanish conquest

Background of the conquistadores

Most conquistadores were Spanish men. A few where from elsewhere, like Juan Valiente who was a black-skinned African. Juan de Bohon (Johann von Bohon), the founder of La Serena and Barlolomeo Flores (Barotholomeus Blumental) are said to have been Germans.[14] Navigator Juan Bautista Pastene was of Genoese origin. Inés Suárez stands out as a rare female conquistadora.

Founding of cities

The conquest of Chile was not carried out directly by the Spanish Crown but by Spaniards that formed enterprises for those purposes and gathered financial resources and soldiers for the enterprise by their own.[15] In 1541 an expedition (enterprise) led by Pedro de Valdivia founded Santiago initiating the conquest of Chile. The first years were harsh for the Spaniards mainly due to their poverty, indigenous rebellions, and frequent conspiracies.[16] The inhabitants of Santiago in the mid-16th century were notoriously poorly dressed as result of a lack of supplies, with some Spanish even resorting to dress with hides from dogs, cats, sea lions, and foxes.[17] The second founding of La Serena in 1549 (initially founded in 1544 but destroyed by natives) was followed by the founding of numerous new cities in southern Chile halting only after Valdivia's death in 1553.[16]

The Spanish colonization of the Americas was characterized by the establishments of cities in the middle of conquered territories. With the founding of each city a number of conquistadores became vecinos of that city being granted a solar and possibly also a chacra in the outskirts of the city, or a hacienda or estancia in more far away parts of the countryside. Apart from land, natives were also distributed among Spaniards since they were considered vital for carrying out any economic activity.[18]

The cities founded, despite defeats in the Arauco War, were: Santiago (1541), La Serena (1544), Concepción (1550), La Imperial, Valdivia, Villarrica (1552), Los Confines (1553), Cañete (1557), Osorno (1558), Arauco (1566), Castro (1567), Chillán (1580), and Santa Cruz de Oñez (1595).

The destruction of the Seven Cities in 1600, and ongoing Arauco War stopped Spanish expansion southward.

Gold mining

Early Spaniards extracted gold from placer deposits using indigenous labour.[19] This contributed to usher in the Arauco War as native Mapuches lacked a tradition of forced labour like the Andean mita and largely refused to serve the Spanish.[20] The key area of the Arauco War were the valleys around Cordillera de Nahuelbuta where the Spanish designs for this region was to exploit the placer deposits of gold using unfree Mapuche labour from the nearby and densely populated valleys.[13] Deaths related to mining contributed to a population decline among native Mapuches.[20] Another site of Spanish mining was the city of Villarrica. At this city the Spanish mined gold placers and silver.[21] The original site of the city was likely close to modern Pucón.[21] However at some point in the 16th century it is presumed the gold placers were buried by lahars flowing down from nearby Villarrica Volcano. This prompted settlers to relocate the city further west at its modern location.[21]

Mining activity declined in the late 16th century as the richest part of placer deposits, which are usually the most shallow, became exhausted.[19] The decline was aggravated by the collapse of the Spanish cities in the south following the battle of Curalaba (1598) which meant for the Spaniards the loss of both the main gold districts and the largest indigenous labour sources.[22]

Compared to the 16th and 18th centuries, Chilean mining activity in the 17th century was very limited.[23]

Southern limit of the conquests

Pedro de Valdivia sought originally to conquer all of southern South America to the Straits of Magellan (53° S). He did however only reach Reloncaví Sound (41°45' S). Later in 1567 Chiloé Archipelago (42°30' S) was conquered, from there on southern expansion of the Spanish Empire halted. The Spanish are thought to have lacked incentives for further conquests south. The indigenous populations were scarce and had ways of life that differed from the sedentary agricultural life the Spanish were accostumed to.[24] The harsh climate in the fjords and channels of Patagonia may also have deterred further expansion.[24] Indeed, even in Chiloé did the Spanish encounter difficulties to adapt as their attempts to base the economy on gold extraction and a "hispanic-mediterranean" agricultural model failed.[25]

Timeline of events

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1540 | December | Pedro de Valdivia takes possession of Chile in the name of the King of Spain. |

| 1541 | February 12 | Santiago is founded. |

| September 11 | Destruction of Santiago. Michimalonco leads a Picunche attack on Santiago, the city is severely damaged but the attack is repelled. | |

| 1544 | September 4 | La Serena is founded by Juan Bohón. |

| 1549 | January 11 | La Serena is destroyed by natives. |

| August 26 | La Serena is refounded. | |

| 1551 | October 5 | Concepción is founded. |

| 1552 | San Felipe de Rauco, La Imperial and Villarrica are founded. | |

| February 9 | The city of Valdivia is founded by Pedro de Valdivia. | |

| 1553 | Los Confines is founded. | |

| December 25 | The battle of Tucapel takes place, governor Pedro de Valdivia is killed after the battle. | |

| 1554 | February 23 | The battle of Marihueñu takes place, Concepción is abandoned and destroyed. |

| October 17 | Jerónimo de Alderete is appointed governor of Chile in Spain by the king but dies on his journey to Chile. | |

| 1557 | April 1 | Francisco de Villagra defeats the Mapuches and kills their leader Lautaro at the battle of Mataquito. |

| April 23 | The new governor García Hurtado de Mendoza arrives in La Serena. | |

| June | García Hurtado de Mendoza arrives in the bay of Concepcion and builds a fort at Penco, then defeats the Mapuche army trying to dislodge him. | |

| October 10 | García Hurtado de Mendoza defeats the Mapuche army in the Battle of Lagunillas. | |

| November 7 | García Hurtado de Mendoza defeats Caupolicán in the Millarupe. | |

| 1558 | January 11 | Cañete founded by Mendoza. |

| February 5 | Pedro de Avendaño captured the Mapuche toqui Caupolicán, later executed by impalement in Cañete. | |

| March 27 | Osorno is founded. | |

| December 13 | Battle of Quiapo, Mendoza defeats the Mapuche and San Felipe de Araucan rebuilt. | |

| 1559 | January 6 | Concepción is refounded. |

| 1561 | Francisco de Villagra succeeds García Hurtado de Mendoza as governor. | |

| 1563 | Cañete is abandoned. | |

| July 22 | Francisco de Villagra dies and is succeeded as governor by his cousin Pedro de Villagra. San Felipe de Araucan is soon abandoned. | |

| August 29 | The territories of Tucumán are separated from the Captaincy General of Chile and transferred to the Real Audiencia of Charcas. | |

| 1564 | February | Concepción is unsuccessfully sieged by native Mapuches. |

| 1565 | A Real Audiencia is established in Concepción. | |

| 1566 | January | San Felipe de Araucan is refounded. |

| 1567 | With the founding of Castro the dominions of the Captaincy General of Chile are extended into Chiloé Archipelago. | |

| 1570 | February 8 | The 1570 Concepción earthquake affects all of south-central Chile. |

| 1575 | The Real Audiencia of Concepción is abolished. | |

| December 16 | The 1575 Valdivia earthquake affects all of southern Chile. | |

| 1576 | April | Valdivia is flooded by a Riñihuazo caused by the 1575 Valdivia earthquake. |

| 1578 | December 5 | Valparaíso is plundered by Francis Drake, the first corsair in Chilean waters. |

| 1580 | June 26 | Chillán is founded. |

| 1584 | March 25 | Rey Don Felipe is founded in the Straits of Magellan by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa. |

| 1587 | Thomas Cavendish finds Rey Don Felipe as a ruin city. | |

| 1594 | May | Fort of Santa Cruz de Oñez is founded and becomes the city of Santa Cruz de Coya the following year. |

| 1598 | December 21 | The battle of Curalaba takes place, governor Martín García Óñez de Loyola is killed during the battle. |

| 1599 | Los Confines, Santa Cruz de Coya and Valdivia are destroyed. | |

| The Real Situado, an annual payment to finance the Arauco War, is established. | ||

| 1600 | La Imperial is destroyed. | |

| 1602 | Villarrica is destroyed. | |

| March 13 | A fort is established in the ruins of Valdivia. | |

| 1603 | February 7 | The last inhabitants of Villarrica surrender to the Mapuches and became captives. |

| 1604 | Arauco and Osorno are destroyed. | |

| February 3 | The fort at Valdivia is abandoned. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Conquista de Chile. |

See also

Notes

- Note that the Chiloé Archipelago with its large population is not included in this estimate.

References

- Silva Galdames, Osvaldo (1983). "¿Detuvo la batalla del Maule la expansión inca hacia el sur de Chile?". Cuadernos de Historia (in Spanish). 3: 7–25. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 37–38.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 39.

- Otero 2006, p. 36.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 157.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 29.

- Dillehay, Tom D. (2014). "Archaeological Material Manifestations". In Dillehay, Tom (ed.). The Teleoscopic Polity. Springer. pp. 101–121. ISBN 978-3-319-03128-6.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 56–57.

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 16–19.

- Moulian, Rodrígo; Catrileo, María; Landeo, Pablo (2015). "Afines quechua en el vocabulario mapuche de Luis de Valdivia" [Akins Quechua words in the Mapuche vocabulary of Luis de Valdivia]. Revista de lingüística teórica y aplicada (in Spanish). 53 (2): 73–96. doi:10.4067/S0718-48832015000200004. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- Dillehay, Tom D.; Pino Quivira, Mario; Bonzani, Renée; Silva, Claudia; Wallner, Johannes; Le Quesne, Carlos (2007) Cultivated wetlands and emerging complexity in south-central Chile and long distance effects of climate change. Antiquity 81 (2007): 949–960

- Bengoa 2003, p. 40.

- Zavala C., José Manuel (2014). "The Spanish-Araucanian World of the Purén and Lumaco Valley in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". In Dillehay, Tom (ed.). The Teleoscopic Polity. Springer. pp. 55–73. ISBN 978-3-319-03128-6.

- Elisabeth-Isabel Bongard. Migrante y protagonista de la Reforma Educacional. p. 64

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 87.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 97–99.

- León, Leonardo (1991). La merma de la sociadad indígena en Chile central y la última guerra de los promaucaes (PDF) (in Spanish). Institute of Amerindian Studies, University of St. Andrews. pp. 13–16. ISBN 1873617003.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 109–113.

- Maksaev, Víctor; Townley, Brian; Palacios, Carlos; Camus, Francisco (2006). "6. Metallic ore deposits". In Moreno, Teresa; Gibbons, Wes (eds.). Geology of Chile. Geological Society of London. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9781862392199.

- Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur (in Spanish). Santiago: Catalonia. pp. 252–253. ISBN 956-8303-02-2.

- Petit-Breuilh 2004, pp. 48–49.

-

- Salazar, Gabriel; Pinto, Julio (2002). Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores (in Spanish). LOM Ediciones. p. 15. ISBN 956-282-172-2

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 168.

- Urbina Carrasco, Ximena (2016). "Interacciones entre españoles de Chiloé y Chonos en los siglos XVII y XVIII: Pedro y Francisco Delco, Ignacio y Cristóbal Talcapillán y Martín Olleta" [Interactions between Spaniards of Chiloé and Chonos in the XVII and XVII centuries: Pedro and Francisco Delco, Ignacio and Cristóbal Talcapillán and Martín Olleta] (PDF). Chungara (in Spanish). 48 (1): 103–114. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Torrejón, Fernando; Cisternas, Marco; Alvial, Ingrid and Torres, Laura. 2011. Consecuencias de la tala maderera colonial en los bosques de alece de Chiloé, sur de Chile (Siglos XVI-XIX)*. Magallania. Vol. 39(2):75–95.

Sources

- Pedro de Valdivia, Cartas de Pedro de Valdivia (Letters of Pedro Valdivia), University of Chile: Diarios, Memorias y Relatos Testimoniales: (on line in Spanish)

- Jerónimo de Vivar, Crónica y relación copiosa y verdadera de los reinos de Chile (Chronicle and abundant and true relation of the kingdoms of Chile) ARTEHISTORIA REVISTA DIGITAL; Crónicas de América (on line in Spanish)

- Alonso de Góngora Marmolejo,Historia de Todas las Cosas que han Acaecido en el Reino de Chile y de los que lo han gobernado (1536-1575) (History of All the Things that Have happened in the Kingdom of Chile and of they that have governed it (1536-1575)), University of Chile: Document Collections in complete texts: Cronicles (on line in Spanish)

- Pedro Mariño de Lobera,Crónica del Reino de Chile , escrita por el capitán Pedro Mariño de Lobera....reducido a nuevo método y estilo por el Padre Bartolomé de Escobar. Edición digital a partir de Crónicas del Reino de Chile Madrid, Atlas, 1960, pp. 227-562, (Biblioteca de Autores Españoles ; 569-575). Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (on line in Spanish)

- Melchor Jufré del Águila; Compendio historial del Descubrimiento y Conquista del Reino de Chile (Historical compendium of the Discovery and Conquest of the Kingdom of Chile), University of Chile: Document Collections in complete texts: Cronicles (on line in Spanish)

- Diego de Rosales, “Historia General del Reino de Chile”, Flandes Indiano, 3 tomos. Valparaíso 1877 - 1878.

- [ Historia general de el Reyno de Chile: Flandes Indiano Vol. 1]

- Historia general de el Reyno de Chile: Flandes Indiano Vol. 2

- [ Historia general de el Reyno de Chile: Flandes Indiano Vol. 3]

- Vicente Carvallo y Goyeneche, Descripcion Histórico Geografía del Reino de Chile (Description Historical Geography of the Kingdom of Chile), University of Chile: Document Collections in complete texts: Chronicles (on line in Spanish)