Curry

Curry is a variety of dishes originating in the Indian subcontinent that use a complex combination of spices or herbs, usually including ground turmeric, cumin, coriander, ginger, and fresh or dried chilies. In southern India, where the word originated, curry leaves, from the curry tree, are also an integral ingredient.[1] Turmeric is known as the main spice in curry, which has a warm, bitter taste and is frequently used to flavor or color curry powders, mustards, butters, and cheeses. Curry is generally prepared in a sauce.[2]

A variety of vegetable curries from India | |

| Place of origin | Indian subcontinent |

|---|---|

| Region or state | Worldwide |

| Main ingredients | Spices, herbs, usually fresh or dried hot peppers or chillies |

There are many varieties of dishes called "curries." For example, in original traditional cuisines, the precise selection of spices for each dish is a matter of national or regional cultural tradition, religious practice, and, to some extent, family preference. Such dishes are called by specific names that refer to their ingredients, spicing, and cooking methods.[3] Spices are used both whole and ground, cooked or raw, and they may be added at different times during the cooking process to produce different results. The main spices found in most curry powders of the Indian subcontinent are coriander, cumin, and turmeric. A wide range of additional spices may be included depending on the geographic region and the foods being included (fish, lentils, red or white meat, rice, and vegetables).[4] Curry powder, a commercially prepared mixture of spices marketed in the West, was first exported to Britain in the 18th Century when Indian merchants sold a traditionally used general concoction of spices, similar to the "Garam Masala, to the British colonial government and army returning to Britain.

Outside of the Indian subcontinent, "curry" may also be used to describe the various unrelated native dishes of Island Southeast Asia, Mainland Southeast Asia, and Oceania which use coconut milk or spice pastes and are commonly eaten over rice (like the Filipino ginataan and Thai gaeng class of dishes).[5]

Dishes called 'curry' may contain fish, meat, poultry, or shellfish, either alone or in combination with vegetables. Additionally, many instead are entirely vegetarian, eaten especially among those who hold ethical or religious proscriptions against eating meat or seafood.

Curries may be either 'dry' or 'wet'. Dry curries are cooked with very little liquid which is allowed to evaporate, leaving the other ingredients coated with the spice mixture. Wet curries contain significant amounts of sauce or gravy based on broth, coconut cream or coconut milk, dairy cream or yogurt, or legume purée, sautéed crushed onion, or tomato purée.

Etymology

Curry is an anglicised form of the Tamil word kaṟi meaning 'sauce' or 'relish for rice' that uses the leaves of the curry tree (Murraya koenigii).[6][7] The word kari is also used in other Dravidian languages, namely in Malayalam, Kannada and Kodava with the meaning of "vegetables (or meat) of any kind (raw or boiled), curry".[8] Kaṟi is described in a mid-17th century Portuguese cookbook by members of the British East India Company,[9] who were trading with Tamil merchants along the Coromandel Coast of southeast India,[10] becoming known as a "spice blend ... called kari podi or curry powder".[10] The first known appearance in its anglicised form (spelled currey) appears in a 1747 book of recipes published by Hannah Glasse.[7][9]

The word cury appears in the 1390s English cookbook, The Forme of Cury,[9] but is unrelated and comes from the Middle French word cuire, meaning 'to cook'[11]

History

Archaeological evidence dating to 2600 BCE from Mohenjo-daro suggests the use of mortar and pestle to pound spices including mustard, fennel, cumin, and tamarind pods with which they flavoured food.[12] Black pepper is native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia and has been known to Indian cooking since at least 2000 BCE.[13]

The original curry pre-dates Europeans' presence in India by about 4,000 years. The three basic ingredients of the spicy stew were ginger, garlic and turmeric, and, using a method called "starch grain analysis", archaeologists at the University of Washington at Vancouver were able to identify the residue of these ancient spices in both skeletons and pottery shards from excavations in India. Examining the human teeth and the residue from the cooking pots, signs of turmeric and ginger were evident.[14][15]

The establishment of the Mughal Empire, in the early 15th century, also influenced some curries, especially in the north. Another influence was the establishment of the Portuguese trading centre in Goa in 1510, resulting in the introduction of chili pepper, tomatoes and potatoes to India from the Americas, as a byproduct of the Columbian Exchange.[16]

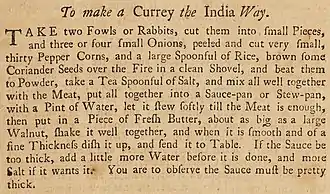

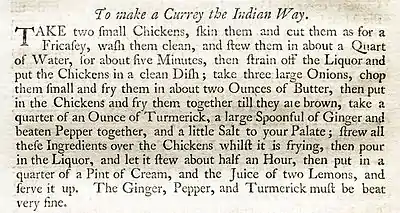

Curry was introduced to English cuisine starting with Anglo-Indian cooking in the 17th century as spicy sauces were added to plain boiled and cooked meats.[17] The 1758 edition of Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery contains a recipe "To make a Currey the India Way".[18] Curry was first served in coffee houses in Britain from 1809, and has been increasingly popular in Great Britain, with major jumps in the 1940s and the 1970s.[19] During the 19th century, curry was also carried to the Caribbean by Indian indentured workers in the British sugar industry. Since the mid-20th century, curries of many national styles have become popular far from their origins, and increasingly become part of international fusion cuisine.

Indian subcontinent

From the culinary point of view, it is useful to consider the Indian subcontinent to be the entire historical region encompassed prior to independence since August 1947; that is, the modern countries of India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It is usual to distinguish broadly between northern and southern styles of Indian cuisine, recognising that within those categories are innumerable sub-styles and variations.[20] The distinction is commonly made with reference to the staple starch: wheat in the form of unleavened breads in the north; rice in the east; rice and millet in the south.[20]

Bangladesh and West Bengal

Bengali cuisine, which refers to the cuisine of Bangladesh and the West Bengal state of India, includes curries, including seafood and fresh fish. Mustard seeds and mustard oil are added to many recipes, as are poppy seeds. Emigrants from the Sylhet district of Bangladesh founded the curry house industry in Britain and in Sylhet some restaurants run by expatriates specialise in British-style Indian food.[21]

Northern India

Curries are the most well-known part of Indian cuisine. Most Indian dishes are usually curry based, prepared by adding different types of vegetables, lentils or meats in the curry. The content of the curry and style of preparation varies per the region. Most curries are water based, with occasional use of dairy and coconut milk. Curry dishes are usually thick and spicy and are eaten along with steamed rice and variety of Indian breads.

Gujarat

Although wet curries play a smaller role in Gujarat than elsewhere, there are a number of vegetarian examples with gravies based on buttermilk or coconut milk. The main ingredient may variously be brinjal (eggplant/aubergine), potatoes, fresh corn kernels, okra, tomatoes, etc. In addition, there are several common kofta dishes which substitute vegetables for meat.[22] Undhiyu, a Gujarati specialty, is a spicy 'wet' mixed-vegetable 'casserole' cooked in an earthenware pot, often eaten during the winter months.

Maharashtra

The curries of Maharashtra vary from mildly spicy to very spicy and include vegetarian, mutton, chicken and fish. Coastal Maharashtrian – Konkani – curries use coconut extensively along with spices. In western Maharashtra, curries are very spicy, often with peanut powder. Vidarbha's cuisine is usually spicier than that of the coastal and southern regions. The ingredients commonly used are besan (gram flour), or chickpea flour, and groundnut powder. As a result of the Mughal rule in the region, the cuisine of Aurangabad has been highly influenced by the North Indian method of cooking. Khandeshi food is very spicy and the most famous dish is shev bhaji. Others include Eggplant bharta (wangyache bhareet), (urid dal), stuffed eggplant (bharleli wangi), bhaakari with thecha etc. The majority of Maharashtrian people are farmers living in the rural areas and therefore their traditional food is very simple.

Punjab

Most Punjabi dishes are prepared using tadka, which is made with the frying of a "masala", which is a mix of ginger, garlic, onions and tomatoes with some dried spices. This is followed by the addition of other ingredients, water, and occasionally milk. Normally spicy, spice levels vary greatly depending on the household itself. Ghee and mustard oil are the most commonly used cooking fats. Many popular Punjabi dishes such as butter chicken and rajma are curry-based. These dishes are usually served with steamed rice and chapatis.

Rajasthan

Rajasthani cuisine was influenced both by the war-like lifestyles of its inhabitants and the availability of ingredients in this arid region.[23] Food that could last for several days and could be eaten without heating was preferred. Scarcity of water and fresh green vegetables have each had their effect on the cooking. Hence the curries in Rajasthan are usually made using dry spices and herbs and other dry items like gram flour. Kadhi is a popular gram flour curry, usually served with steamed rice and bread. To decrease the use of water in this desert state they use a lot of milk and milk-products to cook curries. Laal maans is a popular meat curry from Rajasthan.

Southern India

Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

The food in general from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, both with Telugu-speaking natives, is considered the hottest in India. The state, being the leading producer of red chilli and green chilli, influences the liberal use of spices, making their curries, chutneys, savories and pickles the hottest and spiciest in taste.

Goa

Curries known as vindaloo have become well known in Great Britain, America, and elsewhere, where the name is usually used simply to indicate a fiery dish of lamb or chicken frequently including potatoes. Such dishes are far from the Goan originals.

The name "vindaloo" derives from the Portuguese vinha d'alhos or wine (vinho) and garlic (alho), the two definitive flavour ingredients. The dish was originally made with pork, not taboo to the Christian Portuguese. The inclusion of potatoes was a later Indian addition, thought to be the result of confusion with the Hindi word for potato, aloo. Throughout the years "vindaloo" has been altered to appeal to many people by adding spices and different wines.[24]

Karnataka

The curries of Karnataka are typically vegetarian or with meat and fish around mostly coastal areas. They use a wide variety of vegetables, spices, coconut and jaggery. There are dry and sauce-based curries. Some typical sauce-based dishes include saaru, gojju, thovve, huli, majjige huli (which is similar to the kadi made in the north), sagu or kootu, which is eaten mixed with hot rice.

Kerala

Malayali curries of Kerala typically contain shredded coconut paste or coconut milk, curry leaves, and various spices. Mustard seeds are used in almost every dish, along with onions, curry leaves, and sliced red chilies fried in hot oil. Most of the non-vegetarian dishes are heavily spiced. Kerala is known for its traditional sadya, a vegetarian meal served with boiled rice and a host of side dishes such as parippu (green gram), papadum, ghee, sambar, rasam, aviyal, kaalan, kichadi, pachadi, injipuli, Koottukari, pickles (mango, lime), thoran, one to four types of payasam, boli, olan, pulissery, moru (buttermilk), upperi, and banana chips. The sadya is customarily served on a banana leaf.

Tamil Nadu

Tamil cuisine's distinctive flavour and aroma is achieved by a blend and combination of spices including curry leaves, tamarind, coriander, ginger, garlic, chili, pepper, poppy seeds, mustard seeds, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, cumin, fennel or anise seeds, fenugreek seeds, nutmeg, coconut, turmeric root or powder, and rosewater. Lentils, vegetables and dairy products are essential accompaniments and are often served with rice. Traditionally vegetarian foods dominate the menu with a range of non-vegetarian dishes including freshwater fish and seafood cooked with spices and seasoning.

Kashmir

In the West, the best-known Kashmiri curry is rogan josh, a wet curry of lamb with a brilliant red gravy whose colour is derived from a combination of Kashmiri chillies and an extract derived from the red flowers of the cockscomb plant (mawal).[25] Goshtaba (large lamb meatballs cooked in yoghurt gravy) is another curry dish from the Wazwan tradition occasionally found in Western restaurants.[26]

Maldives

The most important curry in the cuisine of the Maldives is cooked with diced fresh tuna and is known as mas riha. Kukulhu riha, chicken curry, is cooked with a different mixture of spices.[27]

Traditional vegetable curries in the Maldives include those that use bashi (eggplant/aubergine), tora (Luffa aegyptiaca), barabō (pumpkin), chichanda (Trichosanthes cucumerina) and muranga (Moringa oleifera), as well as green unripe bananas and certain leaves as their main ingredients. Pieces of Maldive fish are normally added to give the vegetable curry a certain flavour.[28]

Nepal

The curries of Nepalese cuisine have been influenced by its neighbours, mainly India and Tibet. Well known Indian spices are used less. Goat is a popular meat in the Himalayan region of Nepal.

Daal bhaat (rice and lentil soup) is a staple dish of Nepal. Newa cuisine is a type of cuisine developed over centuries by the Newars of Nepal.

Pakistan

Pakistani curries, especially in the provinces of Punjab and Sindh, are basically similar to their counterparts in northern India. Mutton and beef are common ingredients. A typical Pakistani lunch or dinner often consists of some form of bread (such as naan or roti) or rice with a meat or vegetable-based curry. Barbecue style or roasted meats are also very popular in the form of kebabs.

It is worth noting that the term curry is virtually never used inside the country; instead, regional words such as salan or shorba are used to denote what is known outside the country as a "curry".

Several different types of curries exist, depending on the cooking style, such as bhuna, bharta, roghan josh, qorma, qeema, and shorba. A favourite Pakistani curry is karahi, which is either mutton or chicken cooked in a cooking utensil called karahi, which is similar in shape to a wok. Lahori karahi incorporates garlic, ginger, fresh chillies, tomatoes and select spices. Peshawari karahi is another very popular version made with just meat, salt, tomatoes, and coriander.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

The cuisine from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan is somewhat similar to the cuisine of neighbouring Afghanistan. Extreme winters in some areas made the supply of fresh vegetables impossible, so a lot of dried fruits and vegetables are incorporated in the cuisine. The province still produces a large amount of nuts which are used abundantly in traditional cooking, along with cereals like wheat, maize, barley, and rice. Accompanying these staples are dairy products (yoghurt, whey), various nuts, native vegetables, and fresh and dried fruits. Peshawari karahi from the provincial capital of Peshawar is a popular curry all over the country.

Punjab

Cuisine in Pakistani Punjab differs from Indian Punjab on account of contents and religious diet rules. A typical Punjabi meal consists of some form of bread or rice with a salan (curry). Most preparations start with the frying of a masala which is a concoction of ginger, garlic, onions, tomatoes, and dried spices. Various other ingredients are then added. Spice level varies greatly depending on the sub-region as well as the household itself. A popular cooking fat is desi ghee with some dishes enriched with liberal amounts of butter and cream. There are certain dishes that are exclusive to Punjab, such as maash di dal and saron da saag (sarson ka saag). In Punjab and Kashmir, the only dish known as kardhi (curry) is a dish made of dahi (yogurt) and flour dumplings.

Sindh

In Pakistan, the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan border the Arabian Sea. Due to this, the Sindhi cuisine often has abundant use of fish in curries. Among Pakistani food, the Sindhi curries generally tend to be the hottest. The daily food in most Sindhi households consists of wheat-based flatbread (phulka) and rice accompanied by two dishes, one gravy and one dry.

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lankan cuisine, rice, which is usually consumed daily, can be found at any special occasion, while spicy curries are favourite dishes for lunch and dinner. "Rice and curry" refers to a range of Sri Lankan dishes.

Southeast Asia

Burma

Burmese cuisine is based on a very different understanding of curries. The principal ingredients of almost all Burmese curries are fresh onion (which provides the gravy and main body of the curry), Indian spices and red chilies. Usually, meat and fish are the main ingredients for popular curries.

Burmese curries can be generalised into two types – the hot spicy dishes which exhibit north Indian or Pakistani influence, and the milder "sweet" curries. Burmese curries almost overwhelmingly lack coconut milk, setting them apart from most southeast Asian curries.

Regular ingredients include fresh onion, garlic and chili paste. Common spices include garam masala, dried chili powder, cumin powder, turmeric and ngapi, a fermented paste made from either fish or prawns. Burmese curries are quite oily, as the extra oil helps the food to last longer. A spaghetti equivalent called Nan gyi thohk exists, in which wheat or rice noodles are eaten with thick chicken curry.

Indonesia

In Indonesia curry is called kari or kare. The most common type of kari consumed in Indonesia is kari ayam (chicken curry) and kari kambing (goat meat curry). In Aceh and North Sumatra roti cane is often eaten with kari kambing. Other dishes such as gulai and opor are dishes based on curry. They are often highly localised and reflect the meat and vegetables available. They can therefore employ a variety of meats (chicken, beef, water buffalo and goat as in the flavoursome gulai kambing), seafood (such as prawn, crab, mussel, clam, and squid), fish (tuna, mackerel, carp, pangasius, catfish), or vegetables (young jackfruit, common beans, cassava leaf) dishes in a spiced sauce. They use local ingredients such as chili peppers, kaffir lime leaves, lemongrass, galangal, Indonesian bay leaves (salam leaf), candlenuts, turmeric, turmeric leaves, asam gelugur and asam kandis (sour mangosteens similar to tamarind), shrimp paste (terasi), cumin, coriander seed and coconut milk. In Aceh, curries use daun salam koja or daun kari (Murraya koenigii) translated as "curry leaves".

One popular dish, rendang from West Sumatran cuisine, is often described as caramelised beef dry curry. In Indonesia, rendang is usually not considered to be curry since it is richer and contains less liquid than is normal for Indonesian curries. Authentic rendang uses water buffalo meat slow-cooked in thick coconut milk for a number of hours to tenderise, caramelise, and flavour the meat. Opor Ayam is another variation of curry, which tastes very similar to gulai. Opor is usually whitish in colour and uses neither cinnamon nor turmeric, while gulai may contain either or both. Opor is also often part of a family meal around Lebaran, while gulai can be commonly found in Padang restaurants.

Malaysia

Being at the crossroads of ancient trade routes has left a mark on Malaysian cuisine. While curry may have initially found its way to Malaysian shores via the Indian population, it has since become a staple among the Malays and Chinese. Malaysian curries differ from state to state, even within similar ethnic groupings, as they are influenced by many factors, be they cultural, religious, agricultural or economical.

Malaysian curries typically use turmeric-rich curry powders, coconut milk, shallots, ginger, belacan (shrimp paste), chili peppers, and garlic. Tamarind is also often used. Rendang is another form of curry consumed in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines; it is drier and contains mostly meat and more coconut milk than a conventional Malaysian curry. Rendang was mentioned in Malay literature Hikayat Amir Hamzah[29] (1550s) and is popular among Indonesians, Singaporeans and Malaysians. All sorts of things are curried in Malaysia, including mutton, chicken, tofu, shrimp, cuttlefish, fish, eggplants, eggs, and vegetables.

Philippines

In the Philippines, two kinds of curry traditions are seen corresponding with the cultural divide between the Hispanicised north and Indianised/Islamised south. In the northern areas, a linear range of new curry recipes could be seen. The most common is a variant of the native ginataang manok (chicken is cooked in coconut milk) dish with the addition of curry powder, known as the "Filipino chicken curry". This is the usual curry dish that northern Filipinos are familiar with. Similarly, other northern Filipino dishes that can be considered "curries" are usually ginataan (cooked with coconut milk) variants of other native meat or seafood dishes such as adobo, kaldereta, and mechado, that simply add curry powder or non-native Indian spices.[30]

In southern areas of the Visayas, Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago and southern Palawan, various older curry recipes are seen, and owe their origins to the limited influence of the Spanish in these regions that preserved older culinary traditions; as well as closer historical ties to Malay states like the Sultanate of Brunei. These Mindanaoan curries include kulma, synonymous with the Indian korma; tiyula itum which is a beef curry blackened with burned coconut-meat powder; and rendang, also eaten in Indonesia and Malaysia. Meats used in these curries include beef, goat, mutton, lamb, seafood and chicken. Pork is not used, in accordance with Islamic dietary laws.

Thailand

In Thai cuisine, curries are called kaeng, and usually consist of meat, fish or vegetables in a sauce based on a paste made from chilies, onions or shallots, garlic, and shrimp paste.[31] Additional spices and herbs define the type of curry. Local ingredients, such as chili peppers, kaffir lime leaves, lemongrass, galangal are used and, in central and southern Thai cuisine, coconut milk. Northern and northeastern Thai curries generally do not contain coconut milk. Due to the use of sugar and coconut milk, Thai curries tend to be sweeter than Indian curries. In the West, some of the Thai curries are described by colour; red curries use red chilies while green curries use green chilies. Yellow curry—called kaeng kari (by various spellings) in Thai, of which a literal translation could be "curry soup"—is more similar to Indian curries, with the use of turmeric, cumin, and other dried spices. A few stir-fried Thai dishes also use an Indian style curry powder (Thai: phong kari).

Thai curries:

Vietnam

In Vietnam where curry is called cà ri, curry features include coconut milk, potato, sweet potato, taro roots, chicken garnished with coriander, and green onion. It is more soup-like than Indian curry. The curry is usually eaten with a baguette, rice vermicelli or steamed rice. Some dishes use a curry-based stew, such as snail dishes, phá lấu, stewed frogs or eels.

East Asia

China

Although not an integral part of Chinese cuisine, curry powder is added to some dishes in southern part of China. The curry powder sold in Chinese grocery stores is similar to Madras curry powder but with addition of star anise and cinnamon.[32]

Chinese curries (咖哩, gā lǐ) typically consist of chicken, beef, fish, lamb, or other meats, green peppers, onions, large chunks of potatoes, and a variety of other ingredients and spices in a mildly spicy yellow curry sauce, and topped over steamed rice. White pepper, soy sauce, hot sauce or hot chili oil may be applied to the sauce to enhance the flavour of the curry.

The most common Chinese variety of curry sauce is usually sold in powder form. The ethnic Cantonese being dominant in Kuala Lumpur, this yellow Chinese-Malaysian variety was naturally introduced to China by the Cantonese. It features typically in Hong Kong cuisine, where curry is often cooked with brisket or fish balls. Malay satay seems to have been introduced to China with wider success by the ethnic Teochew, who make up the second largest group of Chinese of Singapore and are the dominant group in Thailand.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, curry fish balls are a street snack, and curried brisket is a typical main course in cha chaan teng and fast food restaurants. Despite its name, Singapore-style noodles is also a curried dish that originated in Hong Kong and became popular worldwide.

Macau

The former Portuguese colony of Macau has its own culinary traditions and curry dishes, including Galinha à portuguesa and curry crab. Portuguese sauce (Chinese: 葡汁, Portuguese: Molho português, Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈmoʎu puɾtuˈɣeʃ]) refers to a sauce that is flavoured with curry and thickened with coconut milk.[33]

Japan

Japanese curry (カレー, karē) is usually eaten as karē raisu — curry, rice, and often pickled vegetables, served on the same plate and eaten with a spoon, a common lunchtime canteen dish. It is less spicy and seasoned than Indian and Southeast Asian curries, being more of a thick stew than a curry.

British people brought curry from the Indian colony back to Britain[34] and introduced it to Japan during the Meiji period (1868 to 1912), after Japan ended its policy of national self-isolation (sakoku), and curry in Japan was categorised as a Western dish.[35] Its spread across the country is commonly attributed to its use in the Japanese Army and Navy which adopted it extensively as convenient field and naval canteen cooking, allowing even conscripts from the remotest countryside to experience the dish. The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force traditionally have curry every Friday for lunch and many ships have their own unique recipes.[36]

The standard Japanese curry contains onions, carrots, potatoes, and sometimes celery, and a meat that is cooked in a large pot. Sometimes grated apples or honey are added for additional sweetness and other vegetables are sometimes used instead. For the meat, pork, beef, and chicken are the most popular, in order of decreasing popularity. In northern and eastern Japan including Tokyo, pork is the most popular meat for curry. Beef is more common in western Japan, including Osaka, and in Okinawa, chicken is favoured.[37] Curry seasoning is commonly sold in the form of a condensed brick, similar to a bouillon cube, which dissolves in the mixture of meat and vegetables.

Sometimes the curry-rice is topped with breaded pork cutlet (tonkatsu); this is called "katsukarē". Korokke (potato croquettes) are also a common topping.

Apart from with rice, curry is also served over noodles, possibly even on top of broth in addition, in dishes such as curry udon and curry ramen. It is also used as the filling in a fried curry bread pastry.

Korea

Though curry was introduced to Korea in the 1940s, the Indian dish was only popularized decades later, when Ottogi entered the Korean food industry by launching its powder-type curry product in 1969.[38][39] Korean curry, usually served with rice, is characterized by the golden yellow colour from turmeric.

Curry tteokbokki, along with curry rice, is one of the most popular curry dishes in Korea. It is made of tteok (rice cakes), eomuk (fish cakes), eggs, vegetables, and curry. Curry can be added to various Korean dishes such as bokkeumbap (fried rice), sundubujjigae (silken tofu stew), fried chicken, vegetable stir-fries, and salads. Curry is also used in Korean-style western food such as pasta and steak, as well as Korean-style Japanese food such as cream udon.

United Kingdom

Curry is very popular in the United Kingdom, with a curry house in nearly every town.[40][41] Such is the popularity of curry in the United Kingdom, it has frequently been called its "adopted national dish".[42] It was estimated that in 2016 there were 12,000 curry houses, employing 100,000 people and with annual combined sales of approximately £4.2 billion.[43]

In general the food offered is Indian food cooked to British taste; however, there is increasing demand for authentic Indian food. As of 2015 curry houses accounted for a fifth of the restaurant business in the U.K. but, being historically a low wage sector, they were plagued by a shortage of labour. Established Indian immigrants from South Asia were moving on to other occupations; there were difficulties in training Europeans to cook curry; and immigration restrictions, which require payment of a high wage to skilled immigrants, had crimped the supply of new cooks.[44]

Historical development

Historically, the word "curry" was first used in British cuisine to denote dishes of meat (often leftover lamb) in a Western-style sauce flavoured with curry powder.

The first curry recipe in Britain appeared in The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse in 1747.[45] The first edition of her book used only black pepper and coriander seeds for seasoning of "currey". By the fourth edition of the book, other ingredients such as turmeric and ginger were called for. The use of hot spices was not mentioned, which reflected the limited use of chili in India — chili plants had only been introduced into India around the late 16th century and at that time were only popular in southern India.

Many curry recipes are contained in 19th century cookbooks such as those of Charles Elmé Francatelli and Mrs Beeton. In Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, a recipe for curry powder is given that contains coriander, turmeric, cinnamon, cayenne, mustard, ginger, allspice and fenugreek; although she notes that it is more economical to purchase the powder at "any respectable shop".[46]

According to legend, one 19th century attempt at curry resulted in the invention of Worcestershire sauce.[47]

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, curry grew increasingly popular in Britain owing to the large number of British civil servants and military personnel associated with the British Raj. Following World War II, curry became even more popular in Britain owing to the large number of immigrants from South Asia.

Curry has become an integral part of British cuisine, so much so that, since the late 1990s, chicken tikka masala has been referred to as "a true British national dish".[48]

Other British curry derivatives include "Coronation chicken", a cold dish, often used as a sandwich filling, invented to commemorate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 – and curry sauce (or curry gravy), usually served warm with traditional British fast food dishes such as chips. Curry sauce occasionally includes sultanas or other dried fruits.

Curry house

In 1810, the entrepreneur Sake Dean Mahomed, from the Bengal Presidency, opened the first Indian curry house in England: the Hindoostanee Coffee House in London.[49] (Curry was served prior to this in some London coffee houses.)[50]

The first modern "upscale" Indian restaurant in Britain is thought to have been The Shafi in 1915,[51] followed by Veeraswamy in London's Regent Street, founded in 1926;[52] the latter is still standing and is the oldest surviving Indian restaurant in Britain.[53][54]

Bengalis in the UK settled in big cities with industrial employment. In London, they settled in the East End, which for centuries has been the first port of call for many immigrants working in the docks and shipping from east Bengal. Their regular stopover paved the way for food and curry outlets to be opened up catering for an all-male workforce as family migration and settlement took place some decades later. Brick Lane in the East London Borough of Tower Hamlets is famous for its many curry houses.

Until the early 1970s, more than three-quarters of Indian restaurants in Britain were identified as being owned and run by people of Bengali origin. Most were run by migrants from East Pakistan, which became Bangladesh in 1971. Bangladeshi restaurateurs overwhelmingly come from the northeastern division of Sylhet. Until 1998, as many as 85% of curry restaurants in the UK were British Bangladeshi restaurants,[55] but in 2003 this figure declined to just over 65%.[56] The dominance of Bangladeshi restaurants is generally declining in some parts of London and the further north one travels. In Glasgow, there are more restaurants of Punjabi origin than any other.[57]

In the early 2010s the popularity of the curry house saw a decline. This has been attributed to the sale of this style of food in generic restaurants, increased home cooking of this style of food with easy supermarket availability of ingredients, and immigration restrictions brought in from 2008 making the availability of low-wage chefs and other staff difficult.[58][59]

Regardless of the ethnic origin of a restaurant's ownership, the menu will often be influenced by the wider South Asia (sometimes including Nepalese dishes), and sometimes cuisines from further afield (such as Persian dishes). Some British variations on Indian food are now being exported from the U.K. to India.[60] Curry restaurants of more-or-less the British style are also popular in Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

This cuisine is characterised by the use of a common base for all the sauces to which spices are added when individual dishes are prepared. The standard "feedstock" is usually a sautéed mixture of onion, garlic and fresh ginger, to which various spices are added, depending on the recipe, but which may include: cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, chilies, peppercorns, cumin and mustard seeds. Ground coriander seed is widely used as a thickening agent, and turmeric is added for colour and its digestive qualities.[61][62][63] Fresh or canned tomatoes and bell peppers are a common addition.

Better quality restaurants will normally make up new sauces on a daily basis, using fresh ingredients wherever possible and grinding their own spices. More modest establishments are more likely to resort to frozen or dried ingredients and pre-packaged spice mixtures.[64]

Terminology

Restaurants in Great Britain have adopted a number of Indian terms to identify popular dishes. Although the names may derive from traditional dishes, often the recipes do not. Representative names include:

- Bhuna – medium, thick sauce, some vegetables (bhunna in Urdu means "to be fried").[65]

- Biryani – spiced rice and meat cooked together and usually served with vegetable curry sauce.

- Curry – the most common name for a meat dish (most often chicken or lamb) with a medium-spicy, brown, gravy-like sauce.

- Dhansak – in the curry house, it may be made with either lamb or chicken and frequently contains pineapple, though this is not original.[66] The name derives from a Parsi dish of mutton cooked with lentils (dal) and vegetables.

- Dupiaza/dopiaza – medium curry (the word means "double onion", referring to the boiled and fried onions used as its primary ingredient).

- Jalfrezi – onion, green chili and a thick sauce.

- Kofta – refers to dishes containing meatballs (most frequently lamb or beef), or vegetable meat-substitutes (most often ground nuts).

- Korma/kurma – mild, yellow in colour, with almond and coconut powder.

- Madras curry – "the standard hot, slightly sour curry at the Indian restaurant."[67]

- Pasanda – in the UK, a mild curry sauce made with cream, coconut milk, and almonds or cashews, served with lamb, chicken, or king prawns (US: jumbo shrimp). The name was derived from a Mughlai dish of lamb strips beaten to make them tender.

- Naga curry – relatively new extremely hot dish with unique savoury taste made with the highly aromatic Naga Morich or Bhut Jolokia chilli pepper.

- Pathia – a hot curry, generally similar to a "Madras" with the addition of lemon juice and tomato purée.

- Phaal – "this is the hottest curry the restaurants can make. There is nothing like it in India – it is pure invention."[68]

- Roghan josh – a medium-spicy curry, usually of lamb/beef with a deep red sauce containing tomatoes and paprika. It derives from a Kashmiri dish of the same name.

- Sambar – medium-heat, sour curry made with lentils and tamarind.

- Vindaloo – generally regarded as the classic "hot" restaurant curry. Progressively hotter versions are sometimes called "tindaloo" and "bindaloo".[67]

The tandoor was introduced into Britain in the 1960s, and tandoori and tikka chicken became popular dishes.[69][70]

Other dishes may feature with varying strengths, with those of north Indian origin, such as butter chicken, tending to be mild, and recipes from the south of India tending to be hotter.

Balti

Baltis are a style of curry thought to have been developed in Birmingham, England[71] which have spread to other western countries and are traditionally cooked and served in the same pot, typically made of cast iron, called karahi or balty.[72]

South Africa

African curries, Cape Malay curries and Natal curries include the traditional Natal curry, the Durban curry, bunny chow, and roti rolls. South African curries appear to have been founded in two distinct regions – one in the east (KwaZulu-Natal) and the other in the west (Western Cape) – with a variety of other curries developing across the country over the late 20th century and early 21st century to include ekasi, coloured, and Afrikaner curries.[73]

Durban has the largest single population of Indians outside of India, who have been developing traditional Natal curries since their arrival in the late 19th century.[74] Natal curries are mostly based on South Indian dishes and mostly consist of simple spiced lamb and chicken dishes (with large amounts of ghee and oils), but also include very complex and elaborate seafood, chicken and lamb specialties (chicken and prawn curry is a Natal favourite). Continental and British recipes have also evolved alongside Indian South African curries. Continental and British versions use mainly traditional recipes with the addition of red wine, milk, cream, vanilla or butter instead of ghee.

Bunny chow or a "set", a South African standard, has spread in popularity throughout the country and into other southern African countries and countries with large South African immigrant populations.[73][74] It consists of either lamb, chicken or bean curry poured into a tunnelled-out loaf of bread to be eaten with one's fingers.[74] The roti roll is another classic takeaway curry that could either be a curry in a flat roti bread (similar to a kebab bread) or the classic "chip, cheese and curry" roll which basically consists of fried chips with melted cheese and curry gravy rolled into a roti roll.

West Indies

In the West Indies, curry is a very popular dish. The Indian indentured servants that were brought over from India by different European powers brought this dish to the West Indies. In Jamaica and Trinidad, curried goat is prominently featured. Curry can be found at both inexpensive and upscale Caribbean restaurants, and ingredients can range from chicken or vegetables to shellfish such as shrimp and scallops. Examples of curries in the West Indies include:

- Guyana: Chicken, goat, duck, shrimp, beef, "aloo" (potato), channa, fish (different varieties) and crab curry are very popular among Guyana, predominantly within Indo-Guyanese people.

- Trinidad and Tobago: Especially curried chicken, crab, duck, goat, beef, shrimp, and "aloo" (potato), along with wild meats.

- Jamaica: Especially curried chicken, goat, beef, fish, lobster, crab, shrimp, potato and vegetables.

- Bahamas: Curried mutton (goat or lamb), curried chicken, curried pork chops.

Other countries

Fiji

In Fiji curries are made in many Indian homes and are eaten with rice or roti. Roti (circle or square) is mainly eaten for breakfast with vegetable curries. Lunch is often dal and rice with some side dishes. Many working people take roti and curry for their lunch. Dinner is usually curry, rice with some chutneys. Curries are normally cooked in vegetable oil. Ghee is mainly used to fry dal, to make puris or sweets. To make a curry, spices like cumin, fenugreek, mustard, and curry leaves are added to the hot oil. Onion is chopped or sliced and garlic crushed and added to the pot. Once the onion and garlic have turned slightly golden then turmeric and garam masala are added. For every 1 tsp turmeric normally 2 tsp masala is added. Salt and chillies are added according to taste. Curry is simmered on low heat until well cooked. Water is added so that it can be mixed with rice. If coriander leaves are available then they are added for extra flavour.

Sometimes potatoes or vegetables are also added to curries to increase volume and make them more nutritious. Often coconut cream is added to seafood curries, such as prawn, crab or fish curries. Dal is often cooked with only turmeric and then fried in cumin, onion, and garlic. Sometimes carrots and leafy vegetables like chauraiya or saijan are added for extra flavor and nutrients.

Similar dishes

- Central Africa: Groundnut stew, though not technically a curry, is a similar style.

- Central Europe: Goulash is a spicy stew or soup usually made with paprika, garlic, potatoes, beef or pork and dill. The dish is not served with rice.

- Ethiopia: Wat, a thick, heavily spiced stew.

- Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga: Generally known as "kare" or "kale", curry is popular in curried lamb, mutton, and chicken stew. Often prepared with coconut milk and accompanied by rice or taro.

- Germany: Currywurst.

- Mexico: Mole, which also originally meant sauce, features different regional variations and combinations of chilies, spices, and chocolate; and recado.

- Netherlands: Frikandel is typically served with curry ketchup.

- Philippines: Kare-kare is a Philippine stew complemented with a thick savory peanut sauce and is typically made with beef, pork, and occasionally offal or tripe. Its similar look to curry gave this dish its name.

Curry powder

"Curry powder", as available in certain western markets, is a commercial spice blend, and first sold by Indian merchants to European colonial traders. This resulted in the export of a derived version of Indian concoction of spices.[75] and commercially available from the late 18th century,[76][77] with brands such as Crosse & Blackwell and Sharwood's persisting to the present.[78] British traders introduced the powder to Meiji Japan, in the mid-19th century, where it became known as Japanese curry.[79]

See also

Gallery

Butter chicken served in an Indian restaurant

Butter chicken served in an Indian restaurant Red roast duck curry (hot and spicy) from Thailand

Red roast duck curry (hot and spicy) from Thailand

Homemade chicken tikka masala

Homemade chicken tikka masala A Balti lamb curry

A Balti lamb curry yoghurt and gram flour curry

yoghurt and gram flour curry Pork Vindaloo in a Goan restaurant

Pork Vindaloo in a Goan restaurant Karnataka Food

Karnataka Food Rogan Josh curry

Rogan Josh curry Curry chicken from Pakistan

Curry chicken from Pakistan Nihari with nihari salad

Nihari with nihari salad Korean curry rice

Korean curry rice Yellow curry

Yellow curry Indian fish Curry

Indian fish Curry Mango Curry from Kerala

Mango Curry from Kerala Buttermilk Curry from Kerala

Buttermilk Curry from Kerala

References

- "Fresh Curry Leaves Add a Touch of India". NPR. 28 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "Curry definition and synonyms". Macmillan Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Collingham, Lizzie (2006). Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 115. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020. "No Indian, however, would have referred to his or her food as a curry. The idea of a curry is, in fact, a concept that the Europeans imposed on India's food culture. Indians referred to their different dishes by specific names ... But the British lumped all these together under the heading of curry."

- Raghavan, S. (2007). Handbook of Spices, Seasonings and Flavourings. CRC Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-8493-2842-8.

- Van Esterik, Penny (2008). Food Culture in Southeast Asia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9780313344206.

- AS, Senthil Kumar (2017). AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF TAMIL LOANWORDS IN ENGLISH, HINDI, SANSKRIT, GREEK, MINOAN AND CYPRO-MINOAN LANGUAGES. senthil kumar a s. p. 83. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Curry". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "kari - A Dravidian Etymological Dictionary". Archived from the original on 23 June 2020.

- Taylor, Anna-Louise (11 October 2013). "Curry: Where did it come from?". BBC: Food Knowledge and Learning. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Sahni, Julie. Classic Indian Cooking. (New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc., c.1980), p.39-40.

- "Thys fourme of cury ys compyled of þe mayster cokes of kyng Richard þe secund ... by assent of Maysters of physik and of phylosophye".--"Things sweet to taste: selections from the Forme of Cury". 1996 ISBN 0-86373-134-1

- Iyer, Raghavan. 660 Curries. (New York, NY: Workman Publishing, c.2008), p.2-3.

- Davidson & Saberi 178

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/people-have-been-eating-curry-for-4500-years-8604270/

- https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/01/indus-civilization-food-how-scientists-are-figuring-out-what-curry-was-like-4500-years-ago.html

- Batsha, Nishant (25 June 2020). "Curry Before Columbus". CONTINGENT. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Collingham, Lizzie (2005). Curry: A Biography. London. p. 115.

- Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011) A History of English Food. London: Random House. Pages 304–305

- "How Britain got the hots for curry". BBC. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Kiple, Kenneth F. and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas, eds. Cambridge World History of Food, The. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, c.2000), vol.2, p.1149f.

- Audrey Gillan (20 June 2002). "From Bangladesh to Brick Lane". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

Some are even opening British-style curry restaurants with names like Taste of Bengal and the Last Days of the Raj.

- Reejhsinghani, Aroona. Vegetarian Wonders from Gujarat. (Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House, c.2002), p.123-128.

- Krishna Gopal Dubey, The Indian Cuisine, PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd., pp.193

- "Fired Up: The History of Vindaloo". SAVEUR. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "Rogan Josh," in Khan Mohammed Sharief Waza, Khan Mohammed Shafi Waza, and Khan Mohammed Rafiq Waza. Wazwaan: Traditional Kashmiri Cuisine. (New Delhi: Roli & Janssen BV, c.2007), p.34.

- "Ghushtaba" in Khan Mohammed Sharief Waza, Khan Mohammed Shafi Waza, and Khan Mohammed Rafiq Waza. Wazwaan: Traditional Kashmiri Cuisine. (New Delhi: Roli & Janssen BV, c.2007), p.37.

- Xavier Romero-Frias. "Eating on the Islands - As times have changed, so has the Maldives' unique cuisine and culture". academia.edu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom, Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- Hikayat Amir Hamzah 1 (Menentang Jin di Bukit Qaf). PTS Fortuna. 2008. p. 10. ISBN 978-983-192-116-6.

- "Pinoy Chicken Curry Recipe". Panlasang Pinoy. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Thai cooking, food thai, Thai menu, pad thai recipe". Thaicooking.nationmultimedia.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Colleen Taylor Sen (15 November 2009). Curry: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-86189-704-6. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Levitt, Alice (28 December 2016). "Our Latest Obsession: Portuguese Chicken at Wing Kee Restaurant". Houstonia. SagaCity Media. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- S&B Company. "History of Japanese curry". Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- Booth, Michael (2017). The Meaning of Rice: And Other Tales from the Belly of Japan. Random House. p. 278. ISBN 9781473545816. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Itoh, Makiko (26 August 2011). "Curry – it's more 'Japanese' than you think". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- The Curry Rice Research Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese)

- "[Best Brand] Ottogi becomes Korea's representative curry product". The Korea Herald. 25 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Sohn, JiAe (24 October 2014). "Ottogi Curry brings Indian cuisine to the table". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Jahangir, Rumeana (26 November 2009). "How Britain got the hots for curry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "National Curry Week: Why Britain loves curry". Fleet Street Communications. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Spinks, Rosie (8 July 2005). "Curry on cooking: how long will the UK's adopted national dish survive?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Moore, Malcolm (8 January 2016). "The great British curry crisis". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura (4 November 2015). "Britons Perturbed by a Troubling Shortage of Curry Chefs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Hannah Glasse (1747). The art of cookery, made plain and easy. OCLC 4942063.

- Isabella Mary Beeton (1861). Mrs. Beeton's book of household management. p. 215. ISBN 0-304-35726-X.

- Lizzie Collingham (2006). "Curry Powder". Curry: A tale of cooks and conquerors. Vintage. pp. 149–150. ISBN 0-09-943786-4.

- "Robin Cook's chicken tikka masala speech". The Guardian. London. 19 April 2001. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- "Curry house founder is honoured". BBC News. London. 29 September 2005. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- Jahangir, Rumeana (26 November 2009). "How Britain got the hots for curry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Grove, Peter and Colleen. The Flavours of History. (London?: Godiva Books, 2011).

- Basu, Shrabani. Curry: The Story of the Nation's Favourite Dish. (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, c.2003), p.127.

- Singh, Rashmi Uday (26 April 2006). "Metro Plus Chennai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Gill, AA (23 April 2006). "Veeraswamy". The Times. London. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- "UK Curry Scene". Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- "Indian Curry in London". Archived from the original on 16 January 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- "The history of the "ethnic" restaurant in Britain". Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- Homa Khaleeli (8 January 2012). "The curry crisis". The Observer. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "Who killed the great British curry house?". The Guardian. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "Can the British curry take off in India?". BBC News. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Curry". www.coursehero.com. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "RhymeZone: coriander seed definitions". www.rhymezone.com. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Wibowo, Hadi. "Herb spice". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Spice It Up: What’s Hot in Seasoning Ingredients". www.ift.org. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Bhuna | Define Bhuna at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Chapman, Pat. Favourite Restaurant Curries. (The Curry Club). (London: Piatkus, c.1988), p.96.

- Chapman, Pat. Favourite Restaurant Curries. (The Curry Club). (London: Piatkus, c.1988), p.34.

- Chapman, Pat. Favourite Restaurant Curries. (The Curry Club). (London: Piatkus, c.1988), p.35.

- Jina (19 February 2011). "Food Detective's Diary: A brief history of Chicken Tikka Masala". Food Detective's Diary. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Wilson, Bee (12 January 2017). "Who killed the curry house?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "Wordhunt appeal list - Balderdash Wordhunt - Oxford English Dictionary". Oed.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Birmingham Balti curry seeks EU protected status". BBC News. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Seid, Shelley (19 October 2017). "Curry is the story of South Africa on a plate". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Govender-Ypma, Ishay (11 November 2017). "The Brutal History of South Africa's Most Famous Curry". Munchies. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Monks discover chicken curry recipe in 200-year-old cookbook - Telegraph, Sophie Jamieson, 13 Jan 2016

- British Library- First British advert for curry powder - 1784

- Nupur Chaudhuri; Margaret Strobel (1992). Western Women and Imperialism: Complicity and Resistance. Indiana University Press. pp. 240–. ISBN 0-253-20705-3.

- Inside the Factory (BBC2), TV review: Greg Wallace lifts the lid on how our curries are made The various ingredients of this inspired show are starting to come together in effective and flavoursome ways - Independent - Sean O'Grady @_seanogrady - Tuesday 14 August 2018 23:00

- Itoh, Makiko (26 August 2011). "Curry — it's more 'Japanese' than you think". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

Further reading

- Chapman, Pat. Curry Club Indian Restaurant Cookbook. London – Piatkus.ISBN 0-86188-378-0 & ISBN 0-86188-488-4 (1984 to 2009)

- Chapman, Pat. The Little Curry Book. London – Piatkus.ISBN 978-0861883646 (1985)

- Achaya, K.T. A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food. Delhi, Oxford University Press (1998)

- Achaya, K.T. A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food. Delhi, Oxford University Press (1998)

- Grove, Peter & Colleen. The Flavours of History. London, Godiva Books (2011)

- Chapman, Pat. India: Food & Cooking. London, New Holland – ISBN 978-1-84537-619-2 (2007)

- Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1994

- David Burton. The Raj at Table. London, Faber and Faber (1993)

- Pat Chapman's Curry Bible. Hodder & St – ISBN 0-340-68037-7 & ISBN 0-340-68037-7 & ISBN 0-340-68562-X & ISBN 0-340-68562-X (1997)

- New Curry Bible, An unaltered edition of Pat Chapman's Curry Bible published by John Blake Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84358-159-8 (2005)

- E.M. Collingham. Curry: A Biography. London, Chatto & Windus, 2005

- An Invitation to Indian Cooking. London, Penguin, 1975

- Jaffrey, Madhur. Various books on curry from 1973 to 2015.

- Chapman, Pat. Petit Plats Curry. Paris. Hachette Marabout. ISBN 2-501-03308-6 (2000)