Noodle

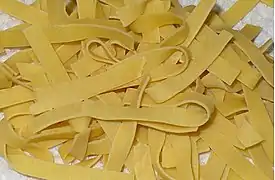

Noodles are a type of food made from unleavened dough which is rolled flat and cut, stretched or extruded, into long strips or strings. Noodles can be refrigerated for short-term storage or dried and stored for future use.

| |

| Place of origin | China |

|---|---|

| Region or state | East Asia |

| Main ingredients | Unleavened dough |

Noodles are usually cooked in boiling water, sometimes with cooking oil or salt added. They are also often pan-fried or deep-fried. Noodle dishes can include a sauce or noodles can be put into soup. The material composition and geocultural origin is specific to each type of a wide variety of noodles. Noodles are a staple food in many cultures (see Chinese noodles, Japanese noodles, Korean noodles, Filipino noodles, Vietnamese noodles and Italian pasta).

History

Origin

The origin of thin, string-like pieces of dough that are often dried and then cooked is hard to pinpoint.[2] What is called noodles is sometimes only considered to be the modern East Asian variety and not the general type and correspondingly its origin is usually listed as Chinese, but when it includes pasta it becomes more controversial.[3][4] The earliest written record of noodles in China is found in a book dated to the Eastern Han period (25–220 CE).[5] It became a staple food for the people of the Han dynasty.[6] Food historians generally estimate that pasta's origin is from among the Mediterranean countries:[4] homogenous mixture of flour and water called itrion as described by 2nd century Greek physician Galen,[7] among 3rd to 5th centuries Palestinians itrium as described by the Jerusalem Talmud[8] and itriyya (Arabic cognate of the Greek word), string-like shapes made of semolina and dried before cooking as defined by the 9th century Aramean physician and lexicographer Isho bar Ali.[9] In 2005 a team of Chinese archaeologists reported finding an earthenware bowl that contained remains of 4000-year-old noodles at the Lajia archaeological site.[10] The findings were said to resemble Lamian, a type of Chinese noodle.[10] Analyzing the husk phytoliths and starch grains present in the sediment associated with the noodles, they were identified as millet belonging to Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica.[10] The findings being noodles was disputed because millet, being gluten-free, isn't suitable for making noodles as we know them.[11][3] Wheat wasn't widely cultivated until the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE).[5]

American food writer and author of On the Noodle Road Jen Lin-Liu notes that documentation of what can be clearly described noodles came about much later on the western side of the world than in China, although she stresses that she doesn't exclude the possibility of two independent inventions.[3][2] The earliest documentation describes small bits of bread dough thrown into a wok of boiling water, eaten even today as mian pian.[2]

East Asia

Wheat noodles in Japan (udon) were adapted from a Chinese recipe as early as the 9th century. Innovations continued, such as noodles made with buckwheat (naengmyeon) were developed in the Joseon Dynasty of Korea (1392–1897). Ramen noodles, based on southern Chinese noodle dishes from Guangzhou but named after the northern Chinese lamian, became common in Japan by 1900.

Central and West Asia

Kesme or Reshteh noodles were eaten by Turkic peoples by the 13th century. Ash reshteh (noodles in thick soup with herbs) is one of the most popular Persian dishes in some Middle Eastern countries, such as Iran.

Europe

In the 1st century BCE, Horace wrote of fried sheets of dough called lagana.[12] However, the cooking method doesn't correspond to the current definition of either a fresh or dry pasta product.[13]

Italy

The first concrete information on pasta products in Italy dates to the 13th or 14th centuries.[14] Pasta has taken on a variety of shapes, often based on regional specializations.

Germany

In the area that would become Germany, documents dating from 1725 mention Spätzle. Medieval illustrations are believed to place this noodle at an even earlier date.[15]

Ancient Israel and diaspora

The Latinized word itrium referred to a kind of boiled dough.[7] Arabs adapted noodles for long journeys in the fifth century, the first written record of dry pasta. Muhammad al-Idrisi wrote in 1154 that itriyya was manufactured and exported from Norman Sicily. Itriya was also known by the Persian Jews during early Persian rule (when they spoke Aramaic) and during Islamic rule. It referred to a small soup noodle, of Greek origin, prepared by twisting bits of kneaded dough into shape, resembling Italian orzo.[16]

Polish Jews

Zacierki is a type of noodle found in Polish Jewish cuisine.[17] It was part of the rations distributed to Jewish victims in the Łódź Ghetto by the Nazis. (Out of the "major ghettos", Łódź was the most affected by hunger, starvation and malnutrition-related deaths.) The diary of a young Jewish girl from Łódź recounts a fight she had with her father over a spoonful of zacierki taken from the family's meager supply of 200 grams a week.[18][19]

Types by primary ingredient

Wheat

Rice

|

Buckwheat

EggEgg noodles are made of a mixture of egg and flour.

Others

|

Types of dishes

- Baked noodles: Boiled and drained noodles are combined with other ingredients and baked. Common examples include many casseroles.

- Basic noodles: These are cooked in water or broth, then drained. Other foods can be added or the noodles are added to other foods (see fried noodles) or the noodles can be served plain with a dipping sauce or oil to be added at the table. In general, noodles are soft and absorb flavors.

- Chilled noodles: noodles that are served cold, sometimes in a salad. Examples include Thai glass noodle salad and cold udon.

- Fried noodles: dishes made of noodles stir fried with various meats, seafood, vegetables, and dairy products. Typical examples include chow mein, lo mein, mie goreng, hokkien mee, some varieties of pancit, yakisoba, Curry Noodles, and pad thai.

- Noodle soup: noodles served in broth. Examples are phở, beef noodle soup, chicken noodle soup, ramen, laksa, saimin, and batchoy.

Preservation

See also

References

- "noodle | Definition of noodle in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "The History of Noodles: How a Simple Food Became a Worldwide Staple". The Atlantic.

- Noone, Yasmin (1 August 2016). "Who invented the noodle, Italy or China?". SBS. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- López, Alfonso (8 July 2016). "The Twisted History of Pasta". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Roach, John (12 October 2005). "4,000-Year-Old Noodles Found in China". National Geographic. pp. 1–2.

- Sinclair & Sinclair 2010, p. 91.

- Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 17.

- Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 29.

- "A medical text in Arabic written by a Jewish doctor living in Tunisia in the early 900s" (Dickie 2008: 21).

- Lu, Houyuan; Yang, Xiaoyan; Ye, Maolin; et al. (13 October 2005). "Culinary archaeology: Millet noodles in Late Neolithic China". Nature. 437 (7061): 967. doi:10.1038/437967a. PMID 16222289.

- Ge, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Jin, Z. (2011). "Can noodles be made from millet? An experimental investigation of noodle manufacture together with starch grain analyses". Archaeometry. 53: 194–204. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2010.00539.x.

- Serventi & Sabban 2002, pp. 15–16 & 24.

- Serventi & Sabban 2002, pp. 15–16.

- Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 10.

- "City Profile: Stuttgart". London: Embassy of Germany, London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

Spätzle is a city specialty.

- Rodinson, Perry & Arberry 2001, p. 253.

- Strybel, Robert; Strybel, Maria (2005). Polish Heritage Cookery. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1124-8.

- Zapruder, Alexandra (2015). Salvaged Pages: Young Writers' Diaries of the Holocaust. Yale University Press. pp. 226–242. ISBN 978-0-300-20599-2.

- Heberer, Patricia (31 May 2011). Children during the Holocaust. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1986-4.

- Kitchen, Leanne (8 January 2019). "Know your noodle: The ultimate guide to Asian noodles". SBS-TV. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Klatskin, Debbie. "Lokshen Noodles". PBS. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Turkish Egg Noodle (Erişte)". Almost Turkish Recipes. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Cloake, Felicity (20 February 2019). "How to make perfect spätzle noodles". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

Bibliography

- Dickie, John (1 October 2010). Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food (Paper). New York: Atria Books. ISBN 0743278070.

- Errington, Frederick et al. eds. The Noodle Narratives: The Global Rise of an Industrial Food into the Twenty-First Century (U. of California Press; 2013) 216 pages; studies three markets for instant noodles: Japan, the United States, and Papua New Guinea.

- Rodinson, Maxime; Perry, Charles; Arberry, Arthur J. (2001). Medieval Arab Cookery (Hardback). United Kingdom: Prospect Books. p. 253. ISBN 0907325912.

- Serventi, Silvano; Sabban, Françoise (2002). Pasta: the Story of a Universal Food. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231124422.

- Sinclair, Thomas R.; Sinclair, Carol Janas (2010). Bread, beer, and the seeds of change: Agriculture's imprint on world history. Wallingford: CABI. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84593-704-1.