Danish nationality law

Danish nationality law is governed by the Constitutional Act the Realm of Denmark (of 1953) and the Consolidated Act of Danish Nationality (of 2003, with amendment in 2004). Danish nationality can be acquired in one of the following ways:[1]

- Automatically at birth if either parent is a Danish citizen, regardless of birthplace, if the child was born on or after 1 July 2014.[2]

- Automatically if a person is adopted as a child under 12 years of age

- By declaration for nationals of another Nordic country

- By naturalisation, that is, by statute

| Danish Citizenship Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of Denmark | |

| |

| Enacted by | Kingdom Government of Denmark |

| Status: Current legislation | |

In December 2018, the law on Danish citizenship was changed so that a handshake was mandatory during the ceremony. The regulation would, among other things, prevent members of Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir from receiving Danish citizenship as they would never shake hands.[3]

Danish nationality can be lost in one of the following ways

- Automatically if a person acquired Danish nationality by birth, but was not born in the Kingdom of Denmark and has never lived in the Kingdom of Denmark by the age of 22 years (unless this would render the person stateless or the person has lived in another Nordic country for an aggregate period of no less than 7 years)

- By court order if a person acquired his or her Danish nationality by fraudulent conduct, for example a sham marriage

- By court order if a person is convicted of violation of one or more provisions of Parts 12 and 13 of the Danish Criminal Code (crimes against national security), unless this would render the person stateless

- By voluntary application to the Minister for Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs (a person who is or who desires to become a national of a foreign country may be released from his or her Danish nationality by such an application)

Naturalisation as a Danish citizen

- One must have permanent residence status in the Kingdom of Denmark in order to become a citizen.

- 9 years of continuous residence, with restricted allowance for an interrupted residence of up to 1 year or 2 years in special circumstances (education, family illness). Continuous residence is not clearly defined, but one must state periods of absence from the Kingdom of Denmark longer than 4 consecutive weeks .

- 8 years of continuous residence for people who are stateless or with refugee status

- Each year of marriage to a Danish citizen reduces the requirement by one year, to a maximum reduction of 3 years. Therefore, a minimum of 6 years of continuous uninterrupted residence is required for people who have been married to Danish nationals for 3 years.

- There is a special and little mentioned clause which allows for absences from the Kingdom of Denmark of longer than 1 or 2 years if one is married to a Danish citizen. The total period of continuous residence should be at least 3 years and it must exceed the total periods of absence, AND either: the period of marriage being at least 2 years or the total period of residence in the Kingdom of Denmark being 10 years less the period of marriage and the 1 year the applicant and Danish spouse have lived together before marriage). One must still have permanent residence.

- If one is married to a Dane working 'for Danish interests' in a foreign country, then this period of absence from the Kingdom of Denmark can count as duration of residence in the Kingdom of Denmark.

According to Statistics Denmark, 3,267 foreigners living in Denmark replaced their foreign citizenship with Danish citizenship in 2012. A total of 71.4% of all those who were naturalized in 2012 were from the non-Western world. Half of all new Danish citizenships in 2012 were given to people from Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkey, Somalia and Iran.[4]

Crime

Immigrants who have committed crimes may be denied Danish citizenship. For instance, immigrants who have received a prison sentence of one year or more, or at least three months for crimes against a person cannot receive citizenship. Convictions which have resulted in a fine also carries with it a time period for immigrants, where citizenship applications are rejected up to 4.5 years after the fine. Upon several offences, the period is extended by 3 years.[5]

Dual citizenship

In October 2011, the newly elected centre-left coalition government indicated its intention to permit dual citizenship.[6][7]

On 18 December 2014, Parliament passed a bill to allow Danish citizens to become foreign nationals without losing their Danish citizenship, and to allow foreign nationals to acquire Danish citizenship without renouncing their prior citizenship. A provision in the bill also allows former Danish nationals who lost their citizenship as a result of accepting another to reobtain Danish citizenship. This provision expires in 2020. A separate provision, lasting until 2017, allows current applicants for Danish citizenship who have been approved under the condition they renounce their prior citizenship to retain their prior nationality as they become Danish citizens. The law came into force on 1 September 2015.[8]

Anyone with Danish (or other) citizenship may be required by a country of which they are also citizens to give up their other (Danish) citizenship, although this cannot be enforced outside the jurisdiction of the country in question. For example Japan does not permit multiple citizenship, while Argentina has no restrictions.

Citizenship of the European Union

Citizenship of the European Union for Danish citizens varies in each part of The unity of the Realm.

Denmark

Danish citizens in Denmark proper are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[9] When in a non-EU country where there is no Danish embassy, Danish citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[10][11] Danish citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[12]

Greenland

Greenland joined the European Economic Community along with Denmark proper in 1973 but left in 1985. Although Greenland is not part of the European Union, but remains associated with the EU through its OCT-status. The associated relationship with the EU also means that Greenlandic nationals are EU citizens.[13] This allows Greenlanders to move and reside freely within the EU.

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands have never been part of the EU or its predecessors, and EU treaties do not apply to the islands. Consequently, Danish citizens residing in the Faroe Islands are not EU citizens within the meaning of the treaties. However, they can choose between a non-EU Danish-Faroese passport (which is green and modelled on pre-EU Danish passport) or a regular Danish EU passport. Some EU member states may treat Danish citizens residing in the Faroe Islands the same as other Danish citizens and thus as EU citizens.

Concerning citizenship of the European Union as established in the Maastricht Treaty, Denmark proper obtained an opt-out in the Edinburgh Agreement, in which EU citizenship does not replace national citizenship and each member state is free to determine its nationals according to its own nationality law. The Amsterdam Treaty extends this to all EU member states, which renders the Danish opt-out de facto meaningless.

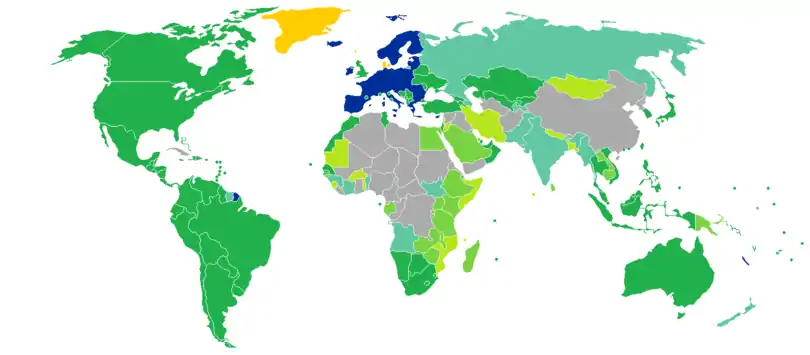

Travel freedom of Danish citizens

Visa requirements for Danish citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of the Kingdom of Denmark. In May 2018, Danish citizens had visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to 185 countries and territories, ranking the Danish passport 5th in the world according to the Henley visa restrictions index.

The Danish nationality is ranked fourth in The Quality of Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Henley Passport Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, besides travel freedom, internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.

See also

Reference

- "Bekendtgørelse af lov om dansk indfødsret".

- "Automatisk erhvervelse af dansk statsborgerskab". Justitsministeriet (Danish Ministry of Justice). Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Nu skal man give hånd for at få statsborgerskab". Berlingske.dk (in Danish). 20 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "Personer, der har skiftet til dansk statsborgerskab" (= "People who have changed to Danish citizenship"), Danmarks Statistik (= Statistics Denmark), 2012

- "Kriminalitet — Udlændinge- og Integrationsministeriet". uim.dk. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Bramsen, C.B. Danskere i udlandet har også rettigheder Archived 2011-10-18 at the Wayback Machine (in Danish). Politiken.dk. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- Regeringen (October 2011). "regeringsgrundlag (oct. 2011)" (PDF) (in Danish). Denmark: 54–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

Danmark er et moderne samfund i en international verden. Derfor skal det være muligt at have dobbelt statsborgerskab.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Folketinget - L 44 - 2014-15 (oversigt): Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om dansk indfødsret. (Accept af dobbelt statsborgerskab og betaling af gebyr i sager om dansk indfødsret)". Folketinget. Parliament of Denmark. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Denmark". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)" (PDF). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES (OCTS)" (Website). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 14 September 2020.