Taiwanese nationality law

Taiwanese nationality law details the conditions in which a person is a national of the Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan. Civil and political rights usually associated with citizenship (such as voting and residence rights) are tied to an ROC national's domicile, determined by whether they have household registration in Taiwan.

| Nationality Act 國籍法 Guójí Fǎ (Mandarin) Kok-che̍k Hoat (Taiwanese) Koet-sit Fap (Hakka) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Legislative Yuan | |

| Territorial extent | Free area of the Republic of China (includes Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and outlying islands) |

| Enacted | February 5, 1929 |

| Effective | February 5, 1929 |

| Administered by | Ministry of the Interior |

| Amended by | |

| February 9, 2000 (amending the whole law) December 21, 2016 (last amended) | |

| Status: Amended | |

History

Taiwan was governed by the Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty of China, from 1683 to 1895.[1] Following the First Sino-Japanese War, the islands of Taiwan and Penghu were ceded to the Empire of Japan. Residents who chose to remain in ceded territory became Japanese subjects in 1897.[2] Control of these islands was transferred to the Republic of China (which succeeded the Qing government in 1912) after the Second World War in 1945. The Chinese government imposed ROC nationality on local residents in 1946, when the Executive Yuan declared the "restoration" of their status as Chinese nationals. Unlike the cession to Japan, Taiwanese residents could not choose which nationality to retain when the ROC took control.[3] Near the end of the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist government was forced to retreat to Taiwan by the Communist Party, which subsequently established the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Since the conclusion of the war, the ROC has controlled only the Taiwan Area.[4]

The ROC continues to constitutionally claim areas under PRC control (mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau) as part of its territory. Because of this, Taiwan treats residents of those areas as ROC nationals. Additionally, because Taiwanese nationality law operates under the principle of jus sanguinis, overseas Chinese and Taiwanese are also regarded as nationals.[5] During the Cold War, both the ROC and PRC governments actively sought the support of overseas Chinese communities in their attempts to secure the position as the legitimate sole government of China. The ROC also encouraged overseas Chinese businessmen to settle in Taiwan to facilitate economic development. Regulations concerning evidence of ROC nationality by descent were particularly lax during this period, allowing many overseas Chinese the right to settle in Taiwan.[6]

From the late 1980s, Taiwan developed a stronger sense of local national identity and more readily asserted its separate identity from that of China. Legal reforms between 1999 and 2002 greatly reduced the ease by which further grants of ROC nationality were made to overseas Chinese and restricted citizenship rights only to those with household registration in Taiwan.[7]

Nationals of Mongolia, which was part of Qing China until 1911, were also regarded as if they were mainland Chinese residents until 2002, when the Mainland Affairs Council removed the country from the administrative definition of the Mainland Area. Since then, Mongolians have been treated as foreigners and are required to apply for visas before entering Taiwan. Nevertheless, the area of Outer Mongolia remains officially part of ROC territorial claims.[8]

Acquisition and loss of nationality

Legislation granting Republic of China nationality is extremely broad in scope. All persons of ethnic Taiwanese and Chinese origin, regardless if they have resided overseas for an extended period of time, are technically ROC nationals. Consequently, children born abroad to any of these people automatically acquire ROC nationality at birth. Furthermore, because of Taiwan's continuing constitutional claims over areas controlled by the People's Republic of China, PRC nationals from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau are considered ROC nationals by Taiwan.[9] Children born within the Taiwan Area to stateless parents are also ROC nationals at birth.[10]

Foreigners over the age of 20 may naturalize as ROC nationals after residing in Taiwan for more than five years and demonstrating proficiency in Mandarin Chinese.[11] The residency requirement is reduced to three years if an applicant has a Taiwanese spouse or parent.[12] Candidates for naturalization are typically required to renounce their previous nationalities unless they are workers in a reserved occupational field.[13] Unmarried minor children cannot naturalize as ROC nationals independently, but a naturalized parent may apply for them on their behalf.[14]

ROC nationality can be relinquished by application to the Ministry of the Interior, provided that they have acquired another nationality or are married to foreign nationals.[15] The status may be deprived if it was fraudulently acquired.[16] All Taiwanese nationals who obtain hukou in mainland China automatically have their passports cancelled and any residence rights in Taiwan revoked.[17]

Household registration

In practice, exercise of most citizenship benefits, such as suffrage, and labour rights, requires possession of the National Identification Card, which is only issued to persons with household registration in the Taiwan Area aged 14 and older. Note that children of nationals who were born abroad are eligible for Taiwan passports and therefore considered to be nationals, but often they do not hold a household registration so are referred to as "unregistered nationals" in statute. These ROC nationals have no automatic right to stay in Taiwan, nor do they have working rights, voting rights, etc. In a similar fashion, some British passport holders do not have the right of abode in the UK (see British nationality law). Unregistered nationals can obtain a National Identification Card only by settling in Taiwan for one year without leaving, two consecutive years staying in Taiwan for a minimum of 270 days a year or five consecutive years staying 183 days or more in each year.

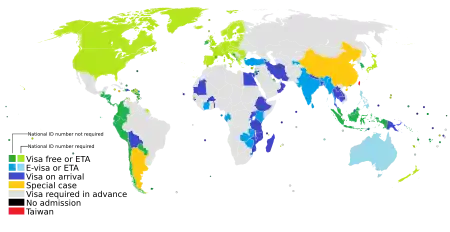

Travel freedom

Visa requirements for Taiwanese citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of Taiwan. In 2014, Taiwanese citizens have visa-free or visa on arrival access to 167 countries and territories, ranking the Taiwan passport 26th in the world according to the Visa Restrictions Index.

Taiwan passport issues to overseas nationals is different than the type of passport issued to Taiwanese citizens with the former having far more restrictions than the latter. For instance, overseas nationals passport holders are required to apply for a visa to enter the Schengen area, whereas no visa is required for the regular passport holders. See the passport article for more information about this practice.

According to the standards and regulations of most international organizations, "Republic of China" is not a recognized nationality. In the international standard ISO 3166-1, the proper nationality designation for persons domiciled in Taiwan is not ROC, but rather TWN. This three-letter code TWN is also the official designation adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization [18] for use on a machine-readable travel document when dealing with entry/exit procedures at immigration authorities outside Taiwan.

Issues

Nationals of the People's Republic of China

The government of the Republic of China does not recognise the People's Republic of China. It claims its official borders encompass all territories governed by the People's Republic of China and persons of these territories are considered to be nationals of the Republic of China. Thus, if the residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau) want to travel to Taiwan, they must do so using the Exit & Entry Permit. Chinese passports, Hong Kong SAR passports, Macau SAR passports, and BN(O) passports are generally not stamped by Taiwan immigration officers. Before 2002, Mongolia was also claimed to be part of the country, the government has affirmed its recognition that Mongolia is a sovereign state and permitted citizens of Mongolia to use their passports to enter Taiwan.

However, by Article 9-1, "[t]he people of the Taiwan Area may not have household registrations in the mainland China or hold passports issued by the Mainland China." If they obtain the passport of the PRC or household registration within mainland China, they will be deprived of their ROC Passport and household registration in Taiwan.[19] [20] It does not apply to Hong Kong and Macau in the sense that, if the residents of Hong Kong and Macau have settled permanently in Taiwan and gain citizenship rights as below, they are allowed to keep the passports as travel documents.

If the residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau) seek to settle permanently in Taiwan and gain citizenship rights, they do not naturalize like citizens of foreign countries. Instead, they merely can establish household registration, which in practice takes longer and is more complicated than naturalization. Article 9 does not apply to overseas Chinese holding foreign nationality who seek to exercise ROC nationality. Such persons do not need to naturalize because they are already legally ROC nationals. Residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau), only after gaining permanent resident status abroad, or otherwise establishing a period of residency defined by the regulations, they become eligible for a Taiwan passport but do not gain benefits of citizenship.

Overseas nationals

Nationals of the Republic of China with household registrations in the Taiwan Area are eligible for the Taiwan passport, and will lose the household registrations in the Taiwan Area, along with their ROC passport, upon holding the Chinese passport. They are different and mutually exclusive in law; most people living in Taiwan only will and only can choose one of these two to identify themselves by current laws.[19][20][21]

Taiwan passports are also issued to overseas Taiwanese and overseas Chinese as a proof of nationality, irrespective of whether they have lived or even set foot in Taiwan. The rationale behind this extension of the principle of jus sanguinis to almost all Chinese regardless of their countries of residence, as well as the recognition of dual citizenships, is to acknowledge the support given by overseas Chinese historically to the Kuomintang regime, particularly during the Xinhai Revolution. The type of passport issued to these individuals is called "Overseas Chinese Passport" of the Republic of China (僑民護照).

References

Citations

- Jacobs 2005, p. 17.

- 日治時期國籍選擇及戶籍處理

- Chen, Yi-nan (20 January 2011). "ROC forced citizenship on unwary Taiwanese". Taipei Times. p. 8. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Lien & Chen 2013, pp. 43–44.

- Selya 2004, pp. 329–330.

- Cheng 2014, p. 138.

- Cheng 2014, pp. 138–139.

- "Taiwan-Mongolia ties move on". Taipei Times. 10 September 2002. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Wang 2011, pp. 170–171.

- Nationality Act Article 2-3.

- Nationality Act Article 3.

- Nationality Act Article 4.

- Nationality Act Article 9.

- Nationality Act Article 7.

- Nationality Act Article 11.

- Nationality Act Article 19.

- Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area Article 9-1.

- "Appendix 1, Three Letter Codes: Codes for designation of nationality, place of birth or issuing State/authority". Machine Readable Travel Documents (PDF). Section IV, Part 3, Volume 1 (Third ed.). Montreal, Quebec, Canada: International Civil Aviation Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-9231-139-1. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- "臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例".

- "Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area".

- "MAC urges public not to use Chinese passports - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com.

Publications

- Cheng, Isabelle (2014). "Home-going or home-making? The citizenship legislation and Chinese identity of Indonesian–Chinese women in Taiwan". In Chiu, Kuei-fen; Fell, Dafydd; Ping, Lin (eds.). Migration to and From Taiwan. Routledge. pp. 135–158. doi:10.4324/9780203076866.

- Jacobs, J. Bruce (2005). ""Taiwanization" in Taiwan's Politics". In Makeham, John; Hsiau, A-chin (eds.). Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora. doi:10.1057/9781403980618_2.

- Lien, Pei-te; Chen, Dean P. (2013). "The evolution of Taiwan's policies toward the political participation of citizens abroad in homeland governance". In Tan, Chee-Beng (ed.). Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora. ISBN 978-0-415-60056-9.

- Selya, Roger Mark (2004). Development and Demographic Change in Taiwan. World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-666-1.

- Wang, Hongzen (2011). "Immigration Trends and Policy Changes in Taiwan". Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 20 (2): 169–194. doi:10.1177/011719681102000203.

Legislation

- Guojifa (國籍法) [Nationality Act] (promulgated and effective February 5, 1929, as amended December 21, 2016) (Taiwan)

- Taiwan Diqu Yu Dalu Diqu Renmin Guanxi Tiaoli (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例) [Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area] (promulgated and effective July 31, 1992, as amended July 24, 2019) (Taiwan)