New Zealand nationality law

New Zealand nationality law details the conditions in which a person holds New Zealand nationality. Regulations apply to the entire Realm of New Zealand, which includes the country of New Zealand itself, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, and the Ross Dependency. Foreign nationals may be granted citizenship if they are permanently resident and live in any part of the Realm. Under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, New Zealand citizens can freely live and work in Australia for any length of time.

| Citizenship Act 1977 | |

|---|---|

| |

| New Zealand Parliament | |

| |

| Citation | 1977 No 61 |

| Territorial extent | Realm of New Zealand (includes New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, and the Ross Dependency) |

| Enacted by | 38th New Zealand Parliament |

| Royal assent | 1 December 1977 |

| Commenced | 1 January 1978 |

| Administered by | Department of Internal Affairs |

| Introduced by | Allan Highet, Minister of Internal Affairs |

| Repeals | |

| British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948 (1948 No 15) | |

| Status: Amended | |

History

Nationality in the British Empire

New Zealand became a part of the British Empire in 1840 after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.[1] Accordingly, British nationality law applied to the colony. All New Zealanders were British subjects, including the indigenous Māori, who were extended all rights as British subjects under the terms of the treaty. Because ambiguous wording in the treaty raised uncertainty as to whether the Māori were actually granted subjecthood or merely the rights of that status, the Native Rights Act 1865 was later passed to affirm their British subject status.[2]

Any person born in New Zealand (or anywhere within Crown dominions) was a natural-born British subject.[3] Foreign nationals who were not British subjects had limited property rights and could not own land. They successfully lobbied the government for the ability to naturalise in 1844.[4] Individuals intending to become British subjects needed to request for their names to be included in annual naturalization ordinances or Acts passed by the Governor or General Assembly that regularly granted foreigners subject status.[2]

Until the mid-19th century, it was unclear whether naturalisation regulations in the United Kingdom were applicable elsewhere in the Empire. Each colony had wide discretion in developing their own procedures and requirements for naturalisation up to that point.[5] In 1847, the Imperial Parliament formalised a clear distinction between subjects who naturalised in the UK and those who did so in other territories. Individuals who naturalised in the UK were deemed to have received the status by imperial naturalisation, which was valid throughout the Empire. Those naturalising in colonies were said to have gone through local naturalisation and were given subject status valid only within the relevant territory;[6] a subject who locally naturalised in New Zealand was a British subject there, but not in England or New South Wales. However, when travelling outside of the Empire, British subjects who were locally naturalised in a colony were still entitled to imperial protection.[7]

Naturalisation continued to be processed through annual personalised legislation until 1866, when the process was streamlined.[2] Individuals living in or intending to reside in New Zealand who met a good character requirement and were able to pay a £1 fee could apply for naturalisation with the Colonial Secretary's Office.[8] British subjects who had already been naturalised in another part of the Empire could apply to be naturalised again in New Zealand without residence requirements.[9] Additionally, foreign women who married British subjects were considered to have automatically naturalised under the new regulations.[10]

Chinese immigration to New Zealand began in the 1860s during the West Coast Gold Rush.[11] Growing hostility and anti-Chinese sentiment along with the rise of colonial nationalism led to a concerted movement within the legislature to restrict Chinese immigration. At least 20 bills written to curb Chinese migration were introduced in the House of Representatives from 1879 to 1920. The first of these to pass was the Chinese Immigrants Act 1881,[12] which limited the number of Chinese migrants who could land in New Zealand to one per ten tons of cargo and imposed a £10 head tax on every Chinese person who entered the colony.[13] These restrictions were tightened to one migrant per 100 tons in 1888,[14] then to one per 200 tons in 1896, along with an increase in the head tax to £100.[15] When the £1 naturalisation fee was reduced in 1882 and later abolished in 1892, Chinese were specifically required to continue paying this fee to naturalise.[16][17] Chinese residents were then completely prohibited from naturalising as British subjects from 1908 to 1952.[18]

The Imperial Parliament formalised British subject status as a common nationality across the Empire with the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914. Dominions that adopted this Act as part of their own nationality laws were authorised to grant subject status to aliens by imperial naturalisation.[19] New Zealand subsequently did so in 1923.[20]

The Cook Islands, Tokelau, and Niue respectively became British protectorates in 1888, 1889, and 1901. Island residents became British subjects at the time when Britain acquired these territories. Britain then ceded administrative control over the Cook Islands and Niue to New Zealand in 1901, and for Tokelau in 1925. This change in administration did not change the status of these islanders, and they continued to be British subjects under New Zealand.[21]

Western Samoa was a German territory from 1900 until the First World War. After the war, it became a League of Nations mandate under New Zealand control. Western Samoans did not automatically become British subjects when New Zealand assumed mandatory authority. Parliament amended nationality law in 1923 and 1928 to allow for Western Samoans to become naturalised British subjects, but those who elected not to naturalise had an unclear status that was not resolved until after Western Samoan independence.[22]

Loosened imperial ties

By the end of the First World War, the Dominions had exercised increasing levels of autonomy in managing their own affairs and each by then had developed a distinct national identity. Britain formally recognised this at the 1926 Imperial Conference, jointly issuing the Balfour Declaration with all the Dominion heads of government, which stated that the United Kingdom and Dominions were autonomous and equal to each other within the British Commonwealth of Nations.[23]

The Statute of Westminster 1931 granted full legislative independence to the Dominions, subject to ratification by local legislatures.[23] Diverging developments in Dominion nationality laws, as well as growing assertions of local national identity separate from that of Britain and the Empire, culminated with the creation of Canadian citizenship in 1946, unilaterally breaking the system of a common imperial nationality.[24] Combined with the approaching independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, comprehensive nationality law reform was necessary at this point to address ideas that were incompatible with the previous system.[25] New Zealand accordingly enacted the British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948 to create its own citizenship, which came into force at the same time as the British Nationality Act 1948 throughout the Empire.[26][27]

All British subjects who were born, naturalised, resident for at least 12 months in New Zealand automatically acquired New Zealand citizenship on 1 January 1949.[28] British subjects born to a father who himself was born or naturalised in New Zealand and British subject women who were married to someone qualifying as a New Zealand citizen also automatically acquired citizenship on that date.[29] Cook Islanders, Niueans, Tokelauans, and British subjects born in Western Samoa became New Zealand citizens automatically as well.[30]

The 1948 Act redefined the term British subject as any citizen of New Zealand or another Commonwealth country.[31] Commonwealth citizen is defined in this Act to have the same meaning.[32] British subject/Commonwealth citizen status co-existed with the citizenships of each Commonwealth country.[33] All Commonwealth and Irish citizens were eligible to become New Zealand citizens by registration, rather than naturalisation, after residing in New Zealand for at least 12 months.[34] Commonwealth and Irish women who were married to New Zealand citizens were eligible to acquire citizenship by registration with no additional requirements.[35] Wives of New Zealand citizens who held foreign nationality, as well as their minor children, were allowed to register as citizens at the discretion of the Minister of Internal Affairs.[36] All other foreign nationals could acquire citizenship by naturalisation after five years of residence and formally notifying the government of their intention to naturalise at least one year prior to their application.[37]

It was not until 1951 that Chinese people were finally allowed by law to apply for permanent residence and citizenship again. However, in practice, they continued to be subject to discrimination. Out of the first 400 applicants who fulfilled the legal requirements for New Zealand citizenship and hence who applied for naturalisation, only 20 applicants who were deemed to be 'the most highly assimilated [and educated] types' were approved.[38] In addition, whilst all other applicants for New Zealand citizenship did not have to renounce their former nationality, Chinese people were required to renounce their Chinese citizenship and to demonstrate that they were 'closer to the New Zealand way of life than to the Chinese'.[38] Citizenship ceremonies were introduced in 1954 for those becoming naturalised New Zealand citizens.

Transition to national citizenship

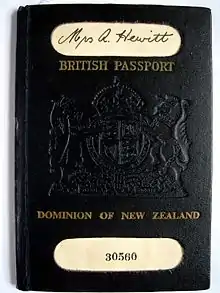

On 1 January 1978, the Citizenship Act 1977 came into force. New Zealand passports no longer contained the phrase "British subject and New Zealand citizen", but instead only stated "New Zealand citizen".[38] Foreign nationals who wanted to become New Zealand citizens were no longer naturalised, but rather received New Zealand citizenship by grant.

Western Samoa became independent in 1962. Subsequent New Zealand legislation caused a significant number of Samoans already living in the country to become illegal immigrants.[22] In 1982, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled that all Western Samoans born between 1924 and 1948 were British subjects and automatically became New Zealand citizens in 1949.[39][40] This decision would have granted New Zealand citizenship for an estimated 100,000 Samoans.[41] However, the New Zealand Parliament effectively nullified this ruling with the Citizenship (Western Samoa) Act 1982.[42] This Act affirmed citizenship for Samoans who were already present in New Zealand before 15 September 1982. Those who enter the country after that date must become permanent residents before acquiring citizenship.[43]

This law has been controversial. A 2003 petition asking the Parliament of New Zealand to repeal the Act attracted 100,000 signatures, and the Samoan rights group Mau Sitiseni filed a petition on the issue with the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 2007.[44]

Māori

Māori were granted "all the Rights and Privileges of British Subjects" under Article 3 of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Their status as British subjects was re-affirmed by the Native Rights Act 1865.[45] However, despite their legal status as British subjects, in practice, over the next century, Māori would be denied some of the privileges[46][47] which white British subjects who moved to New Zealand from Britain enjoyed.[38]

Acquisition and loss of citizenship

Nationality regulations apply to the entire Realm of New Zealand, which includes New Zealand itself, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, and the Ross Dependency.[48]

Individuals born within the Realm receive New Zealand citizenship at birth if at least one parent is a New Zealand citizen or permanent resident.[49] All persons born in the Realm before 2006 automatically received citizenship at birth regardless of the nationalities of their parents.[50] Children born overseas are New Zealand citizens by descent if either parent is a citizen otherwise than by descent.[51] Adopted children are treated as if they were naturally born to the adopting parents at the time of adoption[52] and are subject to the same regulations regarding descent.[53]

Foreigners over the age of 16 may become New Zealand citizens by grant after residing in the Realm for more than five years while possessing indefinite permission to remain.[54] This usually means holding New Zealand permanent residency, but Australian citizens and permanent residents also have an indefinite permission to remain.[55] Applicants must demonstrate proficiency in the English language[56] and be physically present in the country for at least 1,350 days during that five-year period and at least 240 days in each of those five years.[54] Under exceptional circumstances, the physical presence requirement may be reduced to 450 days in a 20-month period.[57] Individuals who are already New Zealand citizens by descent may choose to become citizens by grant after fulfilling the residence requirement to gain the ability to pass citizenship to their children born overseas.[58] New Zealand granted citizenship to an average of 28,000 people per year through the 2010s.[59]

Samoan citizens who enter New Zealand after 14 September 1982 and have indefinite permission to remain in the country are entitled become New Zealand citizens by grant without a minimum residence requirement. Samoans who were already living in New Zealand on that date automatically became New Zealand citizens by grant.[43] Children born in Samoa to Tokelauan mothers seeking medical attention there are treated as if they are born in Tokelau and are New Zealand citizens at birth.[60]

New Zealand citizenship can be relinquished by making a declaration of renunciation to the Minister of Internal Affairs, provided that the declarant already possesses another nationality.[61] Renunciation may be denied if the applying citizen currently lives in New Zealand or the country is at war.[62] Citizenship may be involuntarily deprived from individuals who fradulently acquired it,[63] or from those who possess another nationality and willfully acted against the national interest.[64] Former citizens who renounced their nationality may subsequently apply for nationality restoration, subject to discretionary approval.[65]

Rights and restrictions

New Zealand citizens have the unrestricted right to enter and remain in the country and cannot be deported for any reason.[66] They are entitled to hold New Zealand passports,[67] may purchase real estate without restrictions,[68] eligible for enlistment in the New Zealand Defence Force,[69] and able to vote in all national and local elections.[70] Citizens who are registered electors may stand for office in Parliament.[71] When travelling in foreign countries, citizens may seek consular assistance from New Zealand diplomatic missions.[72]

Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau

Although the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau are all part of the Realm of New Zealand, entry and immigration into these jurisdictions is controlled separately from the country of New Zealand. New Zealand citizens without residency in the other Realm countries do not have an automatic right to live or work in there.[73][74][75]

Australia

Under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, New Zealanders arriving in Australia are granted Special Category Visas, which allow them indefinite permission to live and work there. However, they are generally ineligible for welfare benefits unless they become Australian permanent residents. Prior to 2001, all New Zealanders living in Australia were automatically considered permanent residents; New Zealanders who entered Australia before that year and have remained domiciled there continue to retain that status.[76]

In 2017, dual citizenship with New Zealand proved problematic for multiple Australian politicians, who are ineligible to run for parliament with allegiance to a foreign power under s44(i) of the Australian Constitution. These include New Zealand-born Greens Senator Scott Ludlam, who resigned after discovering that he had not lost his dual citizenship by naturalising in Australia,[77] as well as Deputy Prime Minister and Nationals Leader Barnaby Joyce. His father was born in New Zealand as a British Subject and emigrated to Australia. Living in Australia as a British Subject, he was granted New Zealand citizenship when it was created, thus retroactively making him a New Zealand citizen from birth. This subsequently made Joyce a citizen by descent.[78]

United Kingdom

New Zealand citizens are not considered foreigners when residing in the United Kingdom and are entitled to certain rights as Commonwealth citizens. These include exemption from registration with local police,[79] voting eligibility in UK elections,[80] and the ability to enlist in the British Armed Forces.[81] They are also eligible to serve in non-reserved Civil Service posts,[82] be granted British honours, receive peerages, and sit in the House of Lords.[83] If given indefinite leave to remain (ILR), they are eligible to stand for election to the House of Commons[84] and local government.[85][86][87]

References

Citations

- McMillan & Hood 2016, p. 3.

- McMillan & Hood 2016, p. 4.

- Karatani 2003, pp. 41–42.

- German Settlers Naturalization Ordinance 1844 8 Vict 2, cl 1.

- Karatani 2003, pp. 55–56.

- Historical background information on nationality, p. 8.

- Karatani 2003, p. 56.

- Aliens Act 1866, ss 5, 10.

- Aliens Act 1866, s 9.

- Aliens Act 1866, s 6.

- Fairburn 2004, p. 67.

- Moloughney & Stenhouse 1999, p. 47.

- Chinese Immigrants Act 1881, s 3, 5.

- Chinese Immigrants Act Amendment Act 1888, s 4.

- Chinese Immigrants Act Amendment Act 1896, ss 2, 4.

- Aliens Act Amendment Act 1882, s 3.

- Aliens Act Amendment Act 1892, s 4.

- Fairburn 2004, p. 68.

- Historical background information on nationality, p. 10.

- British Nationality and Status of Aliens (in New Zealand) Act 1923, s 3.

- McMillan & Hood 2016, pp. 11–12.

- McMillan & Hood 2016, p. 12.

- Karatani 2003, pp. 86–88.

- Karatani 2003, pp. 114–115.

- Karatani 2003, pp. 122–126.

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 1(2).

- British Nationality Act 1948, s 34(2).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 16(1).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, ss 16(2), 16(4).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, ss 2(1), 16(3).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 3(1).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 3(2).

- Thwaites 2017, p. 2.

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 8(1).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, s 8(2).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, ss 9(1), 9(2).

- British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948, ss 9(1), 12(1).

- "1. 1840–1948: British subjects - Citizenship - Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Simalae Toala v New Zealand [2000] UNHRC 24, at para 2.5.

- Falema'i Lesa v The Attorney-General (New Zealand) [1982] UKPC 30.

- Simalae Toala v New Zealand [2000] UNHRC 24, at para 2.6.

- Simalae Toala v New Zealand [2000] UNHRC 24, at para 2.7.

- Citizenship (Western Samoa) Act 1982, s 7(1).

- "Samoan rights group to lobby U.N. for New Zealand citizenship". International Herald Tribune: Asia Pacific. 8 March 2007.

- "Native Rights Act 1865". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. 1865. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Levine, Stephen (2006). New Zealand as it Might Have Been. Victoria University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-86473-545-4. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Rashbrooke, Max (2013). Inequality: A New Zealand Crisis. Bridget Williams Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-927131-51-0. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 2(1).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 6(1)(b).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 6(1)(a).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 7(1).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 3(2).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 3(2A).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 8(2)(b).

- "Part 3: Citizenship and permanent residency". Controller and Auditor-General. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 8(2)(e).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 8(7).

- "Types of citizenship: birth, descent and grant". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- "New citizens by grant by country of birth". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 6(5).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 15(1).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 15(3).

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 17.

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 16.

- Citizenship Act 1977, s 15(4).

- Immigration Act 2009, s 13.

- Passport Act 1992, s 3.

- Overseas Investment Amendment Act 2018, s 4(2).

- "Am I eligible?". New Zealand Defence Force. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Electoral Act 1993, s 74(1)(a)(i).

- Electoral Act 1993, s 47(3).

- "Consulate services for New Zealanders". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Tokelau Immigration Regulations 1991, s 4.

- Cook Islands Constitution, s 76A.

- Immigration Act 2011, ss 6–7.

- "Permanent residency and citizenship for NZers in Australia". Government of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Strutt, J; Kagi, J (14 July 2017). "Greens senator Scott Ludlam resigns over failure to renounce dual citizenship". abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Gartrell, Adam; Remeikis, Amy (14 August 2017). "Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce refers himself to High Court over potential dual citizenship". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "UK visas and registering with the police". gov.uk. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Representation of the People Act 1983 (UK), s 4.

- "Nationality". British Army. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Civil Service Nationality Rules" (PDF). Cabinet Office. November 2007. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- British Nationality Act 1981 (UK), sch 7.

- "How can I stand in an election?". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Guidance for candidates and agents: Part 1 of 6 – Can you stand for election?" (PDF). Local elections in England and Wales. Electoral Commission. January 2019. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Guidance for candidates and agents: Part 1 of 6 – Can you stand for election?" (PDF). Local council elections in Scotland. Electoral Commission. April 2017. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Guide for Candidates and Agents: Local Council Elections". Electoral Commission for Northern Ireland. 2019. p. 10. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

Publications

- Fairburn, Miles (2004). "What Best Explains the Discrimination against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860s-1950s?". Journal of New Zealand Studies. 2/3: 65–85. doi:10.26686/jnzs.v0i2/3.90.

- Historical background information on nationality (PDF) (Report). 1.0. Home Office. 21 July 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Karatani, Rieko (2003). Defining British Citizenship: Empire, Commonwealth and Modern Britain. Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0-7146-8298-5. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- McMillan, Kate; Hood, Anna (July 2016). Report on Citizenship Law: New Zealand (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/42648.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moloughney, Brian; Stenhouse, John (1999). "'Drug-besotten, sin-begotten fiends of filth': New Zealanders and the Oriental Other, 1850-1920" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. 33 (1): 43–64. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Thwaites, Rayner (May 2017). Report on Citizenship Law: Australia (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/46449.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Legislation and case law

- "Aliens Act 1866", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Aliens Act Amendment Act 1882", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Aliens Act Amendment Act 1892", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "British Nationality and Status of Aliens (in New Zealand) Act 1923", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "British Nationality Act 1948", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1948 c. 56 (United Kingdom)

- "British Nationality Act 1981", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1981 c. 61 (United Kingdom)

- "Chinese Immigrants Act 1881", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Chinese Immigrants Act Amendment Act 1888 ", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Chinese Immigrants Act Amendment Act 1896 ", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Citizenship Act 1977", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- "Citizenship (Western Samoa) Act 1982", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- "Cook Islands Constitution" (Cook Islands)

- "Electoral Act 1993", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- Falema'i Lesa v The Attorney-General (New Zealand) [1982] UKPC 30, Privy Council

- "German Settlers Naturalization Ordinance 1844 8 Vict 2", New Zealand Legal Information Institute

- "Immigration Act 2009", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- "Immigration Act 2011" (Niue)

- "Overseas Investment Amendment Act 2018", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- "Passport Act 1992", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office

- "Representation of the People Act 1983: Section 4", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1983 c. 2 (s. 4) (United Kingdom)

- Simalae Toala v New Zealand [2000] UNHRC 24, United Nations Human Rights Committee, UN Doc CCPR/C/70/D/675/1995

- "Tokelau Immigration Regulations 1991", legislation.govt.nz, Parliamentary Counsel Office