Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is an island of the British Indian Ocean Territory, an overseas territory of the United Kingdom. It is a militarised atoll just south of the equator in the central Indian Ocean, and the largest of 60 small islands comprising the Chagos Archipelago. It was first discovered by Europeans and named by the Portuguese, settled by the French in the 1790s and transferred to British rule after the Napoleonic Wars. It was one of the "Dependencies" of the British Colony of Mauritius until the Chagos Islands were detached for inclusion in the newly created British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) in 1965.

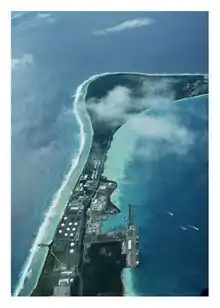

Aerial photograph of Diego Garcia | |

Diego García Location of Diego Garcia | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 7°18′48″S 72°24′40″E |

| Archipelago | Chagos Archipelago |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Indian Ocean |

| Area | 30 km2 (12 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 4,239[1] |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| Designated | 4 July 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1077[2] |

In 1966, the population of the island was 924.[3]:par 23 These people were employed as contract farm workers on primarily coconut plantations owned by the Chagos-Agalega company. Although it was common for local plantation managers to allow pensioners and the disabled to remain in the islands and continue to receive housing and rations in exchange for light work, children after the age of 12 were required to work.[3] In 1964, only 3 of a population of 963 were unemployed.[3] In April 1967, the BIOT Administration bought out Chagos-Agalega for £600,000, thus becoming the sole property owner in the BIOT.[4] The Crown immediately leased back the properties to Chagos-Agalega but the company terminated the lease at the end of 1967.[3]

Between 1968 and 1973, the now unemployed farm workers were forcibly removed from Diego Garcia by the UK Government so a joint US/UK military base could be established on the island.[5] Many were deported to Mauritius and the Seychelles, following which the United States built a large naval and military base, which has been in continuous operation since then.[5] As of August 2018, Diego Garcia is the only inhabited island of the BIOT; the population is composed of military personnel and supporting contractors. It is one of two critical US bomber bases in the Asia Pacific region, along with Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, Pacific Ocean.[6]

The atoll is located 3,535 km (2,197 mi) east of Tanzania's coast, 1,796 km (1,116 mi) south-southwest of the southern tip of India (at Kanyakumari), and 4,723 km (2,935 mi) west-northwest of the west coast of Australia (at Cape Range National Park, Western Australia). Diego Garcia lies at the southernmost tip of the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, a vast underwater mountain range[7] with peaks consisting of coral reefs, atolls, and islands comprising Lakshadweep, the Maldives, and the Chagos Archipelago. Local time is UTC+6 year-round (and since then in permanent DST).[8]

On 23 June 2017, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted in favour of referring the territorial dispute between Mauritius and the UK to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in order to clarify the legal status of the Chagos Islands archipelago in the Indian Ocean. The motion was approved by a majority vote with 94 voting for and 15 against.[9][10]

In February 2019, the International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled that the United Kingdom must transfer the islands to Mauritius as they were not legally separated from the latter in 1965. The ruling is not legally binding.[11] In May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly affirmed the decision of the International Court of Justice and demanded that the United Kingdom withdraw its colonial administration from the Islands and cooperate with Mauritius to facilitate the resettlement of Mauritian nationals in the archipelago.[12][13] In a written statement, the U.S. government said that neither the Americans nor the British have any plans to discontinue use of the military base on Diego Garcia. The statement said in a footnote: "In 2016, there were discussions between the United Kingdom and the United States concerning the continuing importance of the joint base. Neither party gave notice to terminate and the agreement remains in force until 2036".[14]

In June 2020, a Mauritian official offered to allow the United States to retain its military base on the island if Mauritius succeeded in regaining sovereignty over the Chagos archipelago.[15]

History

Before European discovery

According to Southern Maldivian oral tradition, traders and fishermen were occasionally lost at sea and got stranded on one of the islands of the Chagos. Eventually, they were rescued and brought back home. However, the different atolls of the Chagos have no individual names in the Maldivian oral tradition.[16]

Nothing is known of pre-European contact history of Diego Garcia. Speculations include visits during the Austronesian diaspora around 700 CE, as some say the old Maldivian name for the islands originated from Malagasy. Arabs, who reached Lakshadweep and Maldives around 900 CE, may have visited the Chagos.

European discovery

The uninhabited islands are asserted to have been discovered by the Portuguese navigator, explorer, and diplomat Pedro Mascarenhas in 1512, first named as Dom Garcia, in honour of his patron, Dom Garcia de Noronha[17][18] when he was detached from the Portuguese India Armadas[19] during his voyage of 1512–1513. Another Portuguese expedition with a Spanish explorer of Andalusian origin, Diego García de Moguer,[20] rediscovered the island in 1544 and named it after himself. Garcia de Moguer died the same year on the return trip to Portugal in the Indian Ocean, off the South African coast. The misnomer "Diego" could have been made unwittingly by the British ever since, as they copied the Portuguese maps. It is assumed that the island was named after one of its first two discoverers—the one by the name of Garcia, the other with name Diego. Also, a cacography of the saying Deo Gracias ("Thank God") is eligible for the attribution of the atoll. Although the Cantino planisphere (1504) and the Ruysch map (1507) clearly delineate the Maldive Islands, giving them the same names, they do not show any islands to the south which can be identified as the Chagos archipelago.

The Sebastian Cabot map (Antwerp 1544) shows a number of islands to the south which may be the Mascarene Islands. The first map which identifies and names "Los Chagos" (in about the right position) is that of Pierre Desceliers (Dieppe 1550), although Diego Garcia is not named. An island called "Don Garcia" appears on the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius (Antwerp 1570), together with "Dos Compagnos", slightly to the north. It may be the case that "Don Garcia" was named after Garcia de Noronha, although no evidence exists to support this. The island is also labelled "Don Garcia" on Mercator's Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigatium Emendate (Duisburg 1569). However, on the Vera Totius Expeditionis Nauticae Description of Jodocus Hondius (London 1589), "Don Garcia" mysteriously changes its name to "I. de Dio Gratia", while the "I. de Chagues" appears close by.

The first map to delineate the island under its present name, Diego Garcia, is the World Map of Edward Wright (London 1599), possibly as a result of misreading Dio (or simply "D.") as Diego, and Gratia as Garcia. The Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica of Hendrik Hondius II (Antwerp 1630) repeats Wright's use of the name, which is then proliferated on all subsequent Dutch maps of the period, and to the present day.

Settlement of the island

Diego Garcia and the rest of the Chagos islands were uninhabited until the late 18th century. In 1778, the French Governor of Mauritius granted Monsieur Dupuit de la Faye the island of Diego Garcia, and evidence exists of temporary French visits to collect coconuts and fish.[21] Several Frenchmen living in "a dozen huts" abandoned Diego Garcia when the British East India Company attempted to establish a settlement there in April 1786.[21] The supplies of the 275 settlers were overwhelmed by 250 survivors of the wreck of the British East Indian Ship Atlas in May, and the colony failed in October.[22] Following the departure of the British, the French colony of Mauritius began marooning lepers on Diego Garcia,[22] and in 1793, the French established a coconut plantation using slave labour, which also exported cordage made from coconut fibre, and sea cucumbers, known as a delicacy in the Orient.[23]

Diego Garcia became a colony of the UK after the Napoleonic Wars as part of the Treaty of Paris (1814), and from 1814 to 1965 it was administered from Mauritius.[24] On Diego Garcia, the main plantations were located at East Point, the main settlement on the eastern rim of the atoll; Minni Minni, 4.5 km (2.8 mi) north of East Point, and Pointe Marianne, on the western rim, all located on the lagoon side of the atoll rim. The workers lived at these locations, and at villages scattered around the island.

From 1881 until 1888, Diego Garcia was the location of two coaling stations for steamships crossing the Indian Ocean.[25]

In 1882, the French-financed, Mauritian-based Société Huilière de Diego et de Peros (the "Oilmaking Company of Diego and Peros"), consolidated all the plantations in the Chagos under its control.[25]

20th century

In 1914, the island was visited by the German light cruiser SMS Emden halfway through its commerce-raiding cruise during the early months of World War I.[26]

In 1942, the British opened RAF Station Diego Garcia and established an advanced flying boat unit at the East Point Plantation, staffed and equipped by No 205 and No 240 Squadrons, then stationed on Ceylon. Both Catalina and Sunderland aircraft were flown during the course of World War II in search of Japanese and German submarines and surface raiders. At Cannon Point,[27] two 6-inch naval guns were installed by a Royal Marines detachment. In February 1942, the mission was to protect the small Royal Navy base and Royal Air Force station located on the island from Japanese attack.[27] They were later manned by Mauritian and Indian Coastal Artillery troops.[28] Following the conclusion of hostilities, the station was closed on 30 April 1946.[29]

In 1962, the Chagos Agalega Company of the British colony of Seychelles purchased the Société Huilière de Diego et Peros and moved company headquarters to Seychelles.[30]

In the early 1960s, the UK was withdrawing its military presence from the Indian Ocean, not including the airfield at RAF Gan to the north of Diego Garcia in the Maldives (which remained open until 1976), and agreed to permit the United States to establish a naval communication station on one of its island territories there. The United States requested an unpopulated island belonging to the UK to avoid political difficulties with newly independent countries, and ultimately the UK and United States agreed that Diego Garcia was a suitable location.[31]

Purchase by the United Kingdom

To accomplish the UK–US mutual defence strategy, in November 1965, the UK purchased the Chagos Archipelago, which includes Diego Garcia, from the then self-governing colony of Mauritius for £3 million to create the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), with the intent of ultimately closing the plantations to provide the uninhabited British territory from which the United States would conduct its military activities in the region.[31]

In April 1966, the British government bought the entire assets of the Chagos Agalega Company in the BIOT for £600,000 and administered them as a government enterprise while awaiting United States funding of the proposed facilities, with an interim objective of paying for the administrative expenses of the new territory.[30] However, the plantations, both under their previous private ownership and under government administration, proved consistently unprofitable due to the introduction of new oils and lubricants in the international marketplace, and the establishment of vast coconut plantations in the East Indies and the Philippines.[32]

On 30 December 1966, the United States and the UK executed an agreement through an Exchange of Notes which permitted the United States to use the BIOT for defence purposes for 50 years until December 2016, followed by a 20-year extension (to 2036) as long as neither party gave notice of termination in a two-year window (December 2014 – December 2016) and the UK may decide on what additional terms to extend the agreement.[33] No monetary payment was made from the United States to the UK as part of this agreement or any subsequent amendment. Rather, the United Kingdom received a US$14-million discount from the United States on the acquisition of submarine-launched Polaris missiles per a now-declassified addendum to the 1966 agreement.[34]

Arrival of the U.S. Navy

To the United States, Diego Garcia was a prime territory for setting up a foreign military base. According to Stuart Barber—a civilian working for the US Navy at the Pentagon—Diego Garcia was located far away from any potential threats, it was low in a native population and it was an island that was not sought after by other countries as it lacked economic interest. To Barber, Diego Garcia and other acquired islands would play a key role in maintaining US dominance. Here Barber designed the strategic island concept, where the US would obtain as many less populated islands as possible for military purposes. According to Barber, this was the only way to ensure security for a foreign base. Diego Garcia is often referred to as "Fantasy Island" for its seclusion.

The key component in obtaining Diego Garcia was the perceived lack of a native population on the island. Uninhabited until the late 18th century, Diego Garcia had no indigenous population. Its only inhabitants were European overseers who managed the coconut plantations for their absentee landowners and contract workers mostly of African, Indian, and Malay ancestry, known as Chagossians, who had lived and worked on the plantations for several generations. Prior to setting up a military base, the United States government was informed by the British government—which owned the island—that Diego Garcia had a population of hundreds. The eventual number of Chagossians numbered around 1,000.[35]

Regardless of the size of the population, the Chagossians had to be removed from the island before the base could be constructed. In 1968, the first tactics were implemented to decrease the population of Diego Garcia. Those who left the island—either for vacation or medical purposes—were not allowed to return, and those who stayed could obtain only restricted food and medical supplies. This tactic was in hope that those that stayed would leave "willingly".[36] One of the tactics used was that of killing Chagossian pets.[37]

In March 1971, United States Naval construction battalions arrived on Diego Garcia to begin the construction of the communications station and an airfield.[38] To satisfy the terms of an agreement between the UK and the United States for an uninhabited island, the plantation on Diego Garcia was closed in October of that year.[39] The plantation workers and their families were relocated to the plantations on Peros Bahnos and Salomon atolls to the northwest. The by-then-independent Mauritian government refused to accept the islanders without payment, and in 1974, the UK gave the Mauritian government an additional £650,000 to resettle the islanders.[40] Those who still remained on the island of Diego Garcia between 1971 and 1973 were forced onto cargo ships that were heading to Mauritius and the Seychelles.

By 1973, construction of the Naval Communications Station (NAVCOMMSTA) was completed.[41] In the early 1970s, setbacks to United States military capabilities in the region including the fall of Saigon, victory of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the closure of the Peshawar Air Station listening post in Pakistan and Kagnew Station in Eritrea, the Mayaguez incident, and the build-up of Soviet naval presence in Aden and a Soviet airbase at Berbera, Somalia, caused the United States to request, and the UK to approve, permission to build a fleet anchorage and enlarged airfield on Diego Garcia,[42] and the Seabees doubled the number of workers constructing these facilities.[42]

Following the fall of the Shah of Iran and the Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979–1980, the West became concerned with ensuring the flow of oil from the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz, and the United States received permission for a $400-million expansion of the military facilities on Diego Garcia consisting of two parallel 12,000-foot-long (3,700 m) runways, expansive parking aprons for heavy bombers, 20 new anchorages in the lagoon, a deep-water pier, port facilities for the largest naval vessels in the American or British fleet, aircraft hangars, maintenance buildings and an air terminal, a 1,340,000 barrels (213,000 m3) fuel storage area, and billeting and messing facilities for thousands of sailors and support personnel.[42]

Chagos Marine Protected Area

On 1 April 2010, the Chagos Marine Protected Area (MPA) was declared to cover the waters around the Chagos Archipelago. However, Mauritius objected, stating this was contrary to its legal rights, and on 18 March 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that the Chagos Marine Protected Area was illegal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as Mauritius had legally binding rights to fish in the waters surrounding the Chagos Archipelago, to an eventual return of the Chagos Archipelago, and to the preservation of any minerals or oil discovered in or near the Chagos Archipelago prior to its return.[43][44]

Inhabitants

Diego Garcia had no permanent inhabitants when discovered by the Spanish explorer Diego García de Moguer in the 16th century, then in the service of Portugal, and this remained the case until it was settled as a French colony in 1793.[25]

French settlement

Most inhabitants of Diego Garcia through the period 1793–1971 were plantation workers, but also included Franco-Mauritian managers, Indo-Mauritian administrators, Mauritian and Seychellois contract employees, and in the late 19th century, Chinese and Somali employees.

A distinct Creole culture called the Ilois, which means "islanders" in French Creole, evolved from these workers. The Ilois, now called Chagos Islanders or Chagossians since the late-1990s, were descended primarily from slaves brought to the island from Madagascar by the French between 1793 and 1810, and Malay slaves from the slave market on Pulo Nyas, an island off the northwest coast of Sumatra, from around 1820 until the slave trade ended following the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.[45] The Ilois also evolved a French-based Creole dialect now called Chagossian Creole.

Throughout their recorded history, the plantations of the Chagos Archipelago had a population of approximately 1,000 individuals, about two-thirds of whom lived on Diego Garcia. A peak population of 1,142 on all islands was recorded in 1953.[35]

The primary industry throughout the island's colonial period consisted of coconut plantations producing copra and/or coconut oil,[25] until closure of the plantations and relocation of the inhabitants in October 1971. For a brief period in the 1880s, it served as a coaling station for steamships transiting the Indian Ocean from the Suez Canal to Australia.[46]

Expulsion of 1971

All the inhabitants of Diego Garcia were forcibly resettled to other islands in the Chagos Archipelago, Mauritius or Seychelles by 1971 to satisfy the requirements of a UK/United States Exchange of Notes signed in 1966 to depopulate the island when the United States constructed a base upon it.[47] No current agreement exists on how many of the evacuees met the criteria to be an Ilois, and thus be an indigenous person at the time of their removal, but the UK and Mauritian governments agreed in 1972 that 426 families,[48] numbering 1,151 individuals,[40] were due compensation payments as exiled Ilois. The total number of people certified as Ilois by the Mauritian Government's Ilois Trust Fund Board in 1982 was 1,579.[49]

Fifteen years after the last expulsion, the Chagossians received compensation from the British, totalling $6,000 per person; some Chagossians received nothing. The British expulsion action remains in litigation as of 2016.[50][51] Today, Chagossians remain highly impoverished and are living as "marginalized" outsiders on the island of Mauritius and the Seychelles.

After 1971

Between 1971 and 2001, the only residents on Diego Garcia were UK and US military personnel and civilian employees of those countries. These included contract employees from the Philippines and Mauritius, including some Ilois.[52] During combat operations from the atoll against Afghanistan (2001–2006) and Iraq (2003–2006), a number of allied militaries were based on the island including Australian,[53] Japanese, and the Republic of Korea.[54] According to David Vine, "Today, at any given time, 3,000 to 5,000 US troops and civilian support staff live on the island."[55] The inhabitants today do not rely on the island and the surrounding waters for sustenance. Although some recreational fishing for consumption is permitted, all other food is shipped in by sea or air.[56]

In 2004, US Navy recruitment literature described Diego Garcia as being one of the world's best-kept secrets, boasting great recreational facilities, exquisite natural beauty, and outstanding living conditions.[57]

Politics

Diego Garcia is the only inhabited island in the British Indian Ocean Territory, an overseas territory of the United Kingdom, usually abbreviated as "BIOT". The Government of the BIOT consists of a commissioner appointed by the Queen. The commissioner is assisted by an administrator and small staff, and is based in London and is resident in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Originally colonised by the French, Diego Garcia was ceded, along with the rest of the Chagos Archipelago, to the United Kingdom in the Treaty of Paris (1814) at the conclusion of a portion of the Napoleonic Wars.[25] Diego Garcia and the Chagos Archipelago were administered by the colonial government on the island of Mauritius until 1965, when the UK purchased them from the self-governing colony of Mauritius for £3 million, and declared them to be a separate British Overseas Territory.[58] The BIOT administration was moved to Seychelles following the independence of Mauritius in 1968 until the independence of Seychelles in 1976,[24] and to a desk in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London since.[59]

Military administration

UK represents the territory internationally. A local government as normally envisioned does not exist.[60] Rather, the administration is represented in the territory by the officer commanding British Forces on Diego Garcia, the "Brit rep". Laws and regulations are promulgated by the commissioner and enforced in the BIOT by Brit rep.

Of major concern to the BIOT administration is the relationship with the United States military forces resident on Diego Garcia. An annual meeting called "The Pol-Mil Talks" (for "political-military") of all concerned is held at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London to resolve pertinent issues. These resolutions are formalised by an "Exchange of Notes", or, since 2001, an "Exchange of Letters".[39]

Neither the US nor the UK recognises Diego Garcia as being subject to the African Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Treaty, which lists BIOT as covered by the treaty.[61][62][63] It is not publicly known whether nuclear weapons have ever been stored on the island.[64] Noam Chomsky and Peter Sand have observed and emphasized that the US and UK stance is blocking the implementation of the treaty.[65][66]

Transnational political issues

There are two transnational political issues which affect Diego Garcia and the BIOT, through the British government.

- First, the island nation of Mauritius claims the Chagos Archipelago (which is coterminous with the BIOT), including Diego Garcia. A subsidiary issue is the Mauritian opposition to the UK Government's declaration of 1 April 2010 that the BIOT is a marine protected area with fishing and extractive industry (including oil and gas exploration) prohibited.[67]

- Second, the issue of compensation and repatriation of the former inhabitants, exiled since 1973, continues in litigation and as of August 2010 had been submitted to the European Court of Human Rights by a group of former residents.[68] Some groups allege that Diego Garcia and its territorial waters out to 3 nautical miles (6 km) have been restricted from public access without permission of the BIOT Government since 1971.

Prison site allegations

In 2015, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell's former chief of staff, Lawrence Wilkerson, said Diego Garcia was used by the CIA for "nefarious activities". He said that he had heard from three US intelligence sources that Diego Garcia was used as "a transit site where people were temporarily housed, let us say, and interrogated from time to time" and, "What I heard was more along the lines of using it as a transit location when perhaps other places were full or other places were deemed too dangerous or insecure, or unavailable at the moment".[69][70]

In June 2004, the British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw stated that United States authorities had repeatedly assured him that no detainees had passed in transit through Diego Garcia or were disembarked there.[71]

Diego Garcia was rumoured to have been one of the locations of the CIA's black sites in 2005.[72] Khalid Sheikh Mohammed is one of the "high-value detainees" suspected to have been held in Diego Garcia.[73] In October 2007, the Foreign Affairs Select Committee of the British Parliament announced that it would launch an investigation of continued allegations of a prison camp on Diego Garcia, which it claimed were twice confirmed by comments made by retired United States Army General Barry McCaffrey.[74] On 31 July 2008, an unnamed former White House official alleged that the United States had imprisoned and interrogated at least one suspect on Diego Garcia during 2002 and possibly 2003.[75]

Manfred Nowak, one of five of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture, said that credible evidence exists supporting allegations that ships serving as black sites have used Diego Garcia as a base.[76] The human rights group Reprieve alleged that United States-operated ships moored outside the territorial waters of Diego Garcia were used to incarcerate and torture detainees.[77]

Rendition flight refuelling admission

Several groups claim that the military base on Diego Garcia has been used by the United States government for transport of prisoners involved in the controversial extraordinary rendition program, an allegation formally reported to the Council of Europe in June 2007.[78] On 21 February 2008, British Foreign Secretary David Miliband admitted that two United States extraordinary rendition flights refuelled on Diego Garcia in 2002, and was "very sorry" that earlier denials were having to be corrected.[79]

WikiLeaks CableGate disclosures (2010)

According to Wikileaks CableGate documents (reference ID "09LONDON1156"), in a calculated move planned in 2009, the UK proposed that the BIOT become a "marine reserve" with the aim of preventing the former inhabitants from returning to the islands. A summary of the diplomatic cable is as follows:[80]

HMG would like to establish a "marine park" or "reserve" providing comprehensive environmental protection to the reefs and waters of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), a senior Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) official informed Polcouns on 12 May. The official insisted that the establishment of a marine park—the world's largest—would in no way impinge on USG use of the BIOT, including Diego Garcia, for military purposes. He agreed that the UK and United States should carefully negotiate the details of the marine reserve to assure that United States interests were safeguarded and the strategic value of BIOT was upheld. He said that the BIOT's former inhabitants would find it difficult, if not impossible, to pursue their claim for resettlement on the islands if the entire Chagos Archipelago were a marine reserve.

Additionally, Diego Garcia was used as a storage section for US cluster bombs as a way of avoiding UK parliamentary oversight.[81]

Natural history

No species of plants, birds, amphibians, reptiles, molluscs, crustaceans, or mammals is endemic on Diego Garcia or in the surrounding waters. Several endemic fish and aquatic invertebrates are present, though. All plants, wildlife, and aquatic species are protected to one degree or another. In addition, much of the lagoon waters are protected wetlands as a designated Ramsar site, and large parts of the island are nature preserves.[82]

In 2004, the UK applied for, and received, Ramsar site wetlands conservation status for the lagoon and other waters of Diego Garcia.[83]

Geography

Diego Garcia is the largest land mass in the Chagos Archipelago (which includes Peros Banhos, the Salomon Islands, the Three Brothers, the Egmont Islands, and the Great Chagos Bank), being an atoll occupying approximately 174 square kilometres (67 sq mi), of which 27.19 square kilometres (10 sq mi) is dry land.[84] The continuous portion of the atoll rim stretches 64 km (40 mi) from one end to the other, enclosing a lagoon 21 km (13 mi) long and up to 11 km (7 mi) wide, with a 6 km (4 mi) pass opening at the north. Three small islands are located in the pass.[85]

The island consists of the largest continuous dryland rim of all atolls in the world. The dryland rim varies in width from a few hundred metres to 2.4 km. Typical of coral atolls, it has a maximum elevation on some dunes on the ocean side of the rim of 9 m (30 ft) above mean low water. The rim nearly encloses a lagoon about 19 km (12 mi) long and up to 8 km (5.0 mi) wide. The atoll forms a nearly complete rim of land around a lagoon, enclosing 90% of its perimeter, with an opening only in the north. The main island is the largest of about 60 islands which form the Chagos Archipelago. Besides the main island, three small islets are at the mouth of the lagoon: West Island (3.4 ha (8.4 acres)), Middle Island (6 ha (15 acres)) and East Island (11.75 ha (29.0 acres)). A fourth, Anniversary Island, 1 km (1,100 yards) southwest of Middle Island, appears as just a sand bar on satellite images. Both Middle Island and Anniversary Island are part of the Spur Reef complex.[85]

The total area of the atoll is about 170 km2 (66 sq mi). The lagoon area is roughly 120 km2 (46 sq mi) with depths ranging down to about 25 m (82 ft). The total land area (excluding peripheral reefs) is around 30 km2 (12 sq mi). The coral reef surrounding the seaward side of the atoll is generally broad, flat, and shallow around 1 m (3.3 ft) below mean sea level in most locations and varying from 100 to 200 m (330 to 660 ft) in width. This fringing seaward reef shelf comprises an area around 35.2 km2 (14 sq mi). At the outer edge of the reef shelf, the bottom slopes very steeply into deep water, at some locations dropping to more than 450 m (1,500 ft) within 1 km (0.62 mi) of the shore.[85]

In the lagoon, numerous coral heads present hazards to navigation. The shallow reef shelf surrounding the island on the ocean side offers no ocean-side anchorage. The channel and anchorage areas in the northern half of the lagoon are dredged, along with the pre-1971 ship turning basin. Significant saltwater wetlands called barachois exist in the southern half of the lagoon. These small lagoons off of the main lagoon are filled with seawater at high tide and dry at low tide. Scientific expeditions in 1996 and 2006 described the lagoon and surrounding waters of Diego Garcia, along with the rest of the Chagos Archipelago, as "exceptionally unpolluted" and "pristine".[86]

Diego Garcia is frequently subject to earthquakes caused by tectonic plate movement along the Carlsberg Ridge located just to the west of the island. One was recorded in 1812; one measuring 7.6 on the Richter Scale hit on 30 November 1983, at 23:46 local time and lasted 72 seconds, resulting in minor damage including wave damage to a 50-m stretch of the southern end of the island, and another on 2 December 2002, an earthquake measuring 4.6 on the Richter scale struck the island at 12:21 am.[87]

In December 2004, a tsunami generated near Indonesia caused minor shoreline erosion on Barton Point (the northeast point of the atoll of Diego Garcia).[88]

Oceanography

Diego Garcia lies within the influence of the South Equatorial current year-round. The surface currents of the Indian Ocean also have a monsoonal regimen associated with the Asian Monsoonal wind regimen. Sea surface temperatures are in the range of 80–84 °F (27–29 °C) year-round.[89]

Fresh water supply

Diego Garcia is the above-water rim of a coral atoll composed of Holocene coral rubble and sand to the depth of about 36 m (118 ft), overlaying Pleistocene limestone deposited at the then-sea level on top of a seamount rising about 1,800 m (5,900 ft) from the floor of the Indian Ocean. The Holocene sediments are porous and completely saturated with sea water. Any rain falling on the above-water rim quickly percolates through the surface sand and encounters the salt water underneath. Diego Garcia is of sufficient width to minimise tidal fluctuations in the aquifer, and the rainfall (in excess of 102.5 inches/260 cm per year on average)[90] is sufficient in amount and periodicity for the fresh water to form a series of convex, freshwater, Ghyben-Herzberg lenses floating on the heavier salt water in the saturated sediments.[91][92]

The horizontal structure of each lens is influenced by variations in the type and porosity of the subsurface deposits, which on Diego Garcia are minor. At depth, the lens is globular; near the surface, it generally conforms to the shape of the island.[93] When a Ghyben-Herzberg lens is fully formed, its floating nature will push a freshwater head above mean sea level, and if the island is wide enough, the depth of the lens below mean sea level will be 40 times the height of the water table above sea level. On Diego Garcia, this equates to a maximum depth of 20 m. However, the actual size and depth of each lens is dependent on the width and shape of the island at that point, the permeability of the aquifer, and the equilibrium between recharging rainfall and losses to evaporation to the atmosphere, transpiration by plants, tidal advection, and human use.

In the plantation period, shallow wells, supplemented by rainwater collected in cisterns, provided sufficient water for the pastoral lifestyle of the small population. On Diego Garcia today, the military base uses over 100 shallow "horizontal" wells to produce over 560,000 l per day from the "Cantonment" lens on the northwest arm of the island—sufficient water for western-style usage for a population of 3,500. This 3.7 km2 lens holds an estimated 19 million m3 of fresh water and has an average daily recharge from rainfall over 10,000 m3, of which 40% remains in the lens and 60% is lost through evapotranspiration.[94]

Extracting fresh water from a lens for human consumption requires careful calculation of the sustainable yield of the lens by season because each lens is susceptible to corruption by saltwater intrusion caused by overuse or drought. In addition, overwash by tsunamis and tropical storms has corrupted lenses in the Maldives and several Pacific islands. Vertical wells can cause salt upcoming into the lens, and overextraction will reduce freshwater pressure resulting in lateral intrusion by seawater. Because the porosity of the surface soil results in virtually zero runoff, lenses are easily polluted by fecal waste, burials, and chemical spills. Corruption of a lens can take years to "flush out" and reform, depending on the ratio of recharge to losses.[91]

A few natural depressions on the atoll rim capture the abundant rainfall to form areas of freshwater wetlands.[95] Two are of significance to island wildlife and to recharge their respective freshwater lenses. One of these is centred on the northwest point of the atoll; another is found near the Point Marianne Cemetery on the southeast end of the airfield. Other, smaller freshwater wetlands are found along the east side of the runway, and in the vicinity of the receiver antenna field on the northwest arm of the atoll.[96]

Also, several man-made freshwater ponds resulted from excavations made during construction of the airfield and road on the western half of the atoll rim. These fill from rainfall and from extending into the Ghyben-Herzberg lenses found on this island.[97]

Climate

All precipitation falls as rain, characterised by air mass-type showers. Annual rainfall averages 2,603.5 mm (102.50 in), with the heaviest precipitation from September to April. January is the wettest month with 353 mm (13.9 in) of mean monthly precipitation, and August the driest month, averaging 106.5 mm (4.19 in) of mean monthly precipitation.[98]

The surrounding sea surface temperature is the primary climatic control, and temperatures are generally uniform throughout the year, with an average maximum of 30 °C (86 °F) by day during March and April, and 29 °C (84 °F) from July to September. Diurnal variation is roughly 3–4 °C (5.4–7.2 °F), falling to the low 27 °C (81 °F) by night.[98] Humidity is high throughout the year. The almost constant breeze keeps conditions reasonably comfortable.

From December through March, winds are generally westerly around 6 knots (11 km/h). During April and May, winds are light and variable, ultimately backing to an east-southeasterly direction. From June through September, the influence of the Southeast trades is felt, with speeds of 10–15 knots. During October and November, winds again go through a period of light and variable conditions veering to a westerly direction with the onset of summer in the Southern Hemisphere.[98]

Thunderstorm activity is generally noticed during the afternoon and evenings during the summer months (December through March) and when the Intertropical Convergence Zone is in the vicinity of the island.[98]

Diego Garcia is at minimum risk from tropical cyclones due to its proximity to the equator where the coriolis parameter required to organise circulation of the upper atmosphere is minimal. Low-intensity storms have hit the island, including one in 1901, which blew over 1,500 coconut trees;[99] one on 16 September 1944,[100] which caused the wreck of a Royal Air Force PBY Catalina; one in September 1990 which demolished the tent city then being constructed for United States Air Force bomber crews during Operation Desert Storm;[87] and one on 22 July 2007, when winds exceeded 60 kn (110 km/h) and over 250 mm (9.8 in) of rain fell in 24 hours.[87]

The island was somewhat affected by the tsunami caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. Service personnel on the western arm of the island reported only a minor increase in wave activity. The island was protected to a large degree by its favourable ocean topography. About 80 km (50 mi) east of the atoll lies the 650-km-long (400-mile) Chagos Trench, an underwater canyon plunging more than 4,900 m (16,100 ft). The depth of the trench and its grade to the atoll's slope and shelf shore makes it more difficult for substantial tsunami waves to build before passing the atoll from the east. In addition, near-shore coral reefs and an algal platform may have dissipated much of the waves' impact.[101][102] A biological survey conducted in early 2005 indicated erosional effects of the tsunami wave on Diego Garcia and other islands of the Chagos Archipelago. One 200-to-300 m (220-to-330 yd) stretch of shoreline was found to have been breached by the tsunami wave, representing about 10% of the eastern arm. A biological survey by the Chagos Conservation Trust reported that the resulting inundation additionally washed away shoreline shrubs and small to medium-sized coconut palms.[102]

| Climate data for Diego Garcia (extremes 1951–2005) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.4 (93.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.1 (80.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 340 (13.4) |

279 (11.0) |

213 (8.4) |

194 (7.6) |

167 (6.6) |

147 (5.8) |

144 (5.7) |

145 (5.7) |

244 (9.6) |

281 (11.1) |

221 (8.7) |

273 (10.7) |

2,648 (104.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.3 mm) | 22 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 212 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst[103] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[104] | |||||||||||||

Vegetation

The first botanical observations of the island were made by Hume in 1883, when the coconut plantations had been in operation for a full century. Subsequent studies and collections during the plantation era were made in 1885, 1905, 1939, and 1967.[105] Thus, very little of the nature of the precontact vegetation is known.

The 1967 survey, published by the Smithsonian[106] is used as the most authoritative baseline for more recent research. These studies indicate the vegetation of the island may be changing rapidly. For example, J. M. W. Topp collected data annually between 1993 and 2003 and found that on the average three new plant species arrived each year, mainly on Diego Garcia. His research added fully a third more species to Stoddart.[107] Topp and Martin Hamilton of Kew Gardens compiled the most recent checklist of vegetation in 2009.[108]

In 1967, Stoddart described the land area of Diego Garcia as having a littoral hedge of Scaevola taccada, while inland, Cocos nucifera (coconut) was the most dominant tree, covering most of the island. The substory was either managed and park-like, with understory less than 0.5 m in height, or consisted of what he called "Cocos Bon-Dieu" – an intermediate story of juvenile trees and a luxuriant ground layer of self-sown seedlings – causing those areas to be relatively impenetrable.[109]

Also, areas of remnant tropical hardwood forest are at the sites of the plantation-era villages, as well as Casuarina equisetifolia (iron wood pines) woodlands.[95]

In 1997, the United States Navy contracted a vegetation survey that identified about 280 species of terrestrial vascular plants on Diego Garcia.[110] None of these was endemic, and another survey in 2005 identified just 36 species as "native", meaning arriving without the assistance of humans, and found elsewhere in the world.[111] No terrestrial plant species are of any conservation-related concern at present.[112]

Of the 36 native vascular plants on Diego Garcia, 12 are trees, five are shrubs, seven are dicotyledon herbs, three are grasses, four are vines, and five are ferns.[113]

The 12 tree species are: Barringtonia asiatica (fish-poison tree), Calophyllum inophyllum (Alexandrian laurel), Cocos nucifera, Cordia subcordata, Guettarda speciosa, Intsia bijuga, Hernandia sonora, Morinda citrifolia, Neisosperma oppositifolium,[114] Pisonia grandis, Terminalia catappa, and Heliotropium foertherianum. Another three tree species are common, and may be native, but they may also have been introduced by humans: Casuarina equisetifolia, Hibiscus tiliaceus, and Pipturus argenteus.

The five native shrubs are: Caesalpinia bonduc, Pemphis acidula, Premna serratifolia, Scaevola taccada (often mispronounced "Scaveola"), and Suriana maritima.

Also, 134 species of plants are classified as "weedy" or "naturalised alien species", being those unintentionally introduced by man, or intentionally introduced as ornamentals or crop plants which have now "gone native", including 32 new species recorded since 1995, indicating a very rapid rate of introduction.[115] The remainder of the species list consists of cultivated food or ornamental species, grown in restricted environments such as a planter's pot.[116]

In 2004, 10 plant communities were recognized on the atoll rim:[85]

- Calophyllum forest, dominated by Calophyllum inophyllum, with trunks that can grow in excess of 2 m in diameter: This forest often contains other species such as Hernandia sonora, Cocos nucifera, and Guettarda speciosa with a Premna obtusifolia edge. When found on the beaches, Calophyllum often extends over the lagoon water and supports nesting red-footed boobies, as does Barringtonia asiatica found mostly on the eastern arm of the atoll.

- Cocos forest, essentially monotypic (Cocos bon Dieu), with the understory consisting of coconut seedlings

- Cocos-Hernandia forest, dominated by two canopy species—C. nucifera and H. sonora

- Cocos-Guettarda forest, dominated by the canopy species C. nucifera and G. speciosa: The understory consists of a mix of Neisosperma oppositifolium, with Scaevola taccada and Tournefortia argentea on the beach edge.

- Hernandia forest, dominated at the canopy level by H. sonora: The most representative areas of this forest type are on the eastern, undeveloped part of the atoll. Calophyllum inophyllum and C. nucifera are often present. Understory species in this forest are often Morinda citrifolia, Cocos seedlings, and Asplenium nidus (bird's nest fern), and occasionally, N. oppositifolium and G. speciosa.

- Premna shrubland, occurring generally between marshy areas and forested areas: The most conspicuous vegetation is primarily P. obtusifolia, with Casuarina equisetifolia and Scaevola taccada on the margins. The dense groundcover consists of species such as Fimbristylis cymosa, Ipomoea pes-caprae (beach morning glory) and Triumfetta procumbens. Premna shrubland appears mostly adjacent to the developed areas of the atoll, particularly in the well fields.

- Littoral scrub lines almost the entire seashore and lagoon shore of the island. It is dominated by S. taccada, but it also contains scattered coconut trees, G. speciosa and Pisonia grandis. On the seaward side, it also contains Tournefortia argentea and Suriana maritima. On the lagoon side, it may also contain Lepturus repens, Triumfetta procumbens and Cyperus ligularis. Large pockets of Barringtonia asiatica are also on the eastern edge of the lagoon.

- Maintained areas of grasses and sedges routinely mowed: Aerial photographs of the island clearly display large areas of grasslands and park-like savanna upon which the United States military has constructed large outdoor facilities such as antenna fields and the airport.[117]

- Mixed native forest, with no dominant canopy species

- Marshes are divided into three different types: cattail (Typha domingensis), wetland, and mixed species. Cattail marshes contained almost entirely cattails. These areas are often man-made reservoirs or drainages that have been almost entirely monotypic. Wetlands were based upon vegetation that occurred in the area with fresh water. Mixed-species marshes were highly variable and usually had no standing water.

Wildlife

All the terrestrial and aquatic fauna of Diego Garcia are protected, with the exception of certain game fish, rats, and cats; hefty fines are levied against violators.[118]

Crustaceans

The island is a haven for several types of crustacean; "warrior crabs" (Cardisoma carnifex) overrun the jungle at night. The extremely large 4-kilogram (8.8 lb) coconut crab or robber crab (Birgus latro) is found here in large numbers. Because of the protections provided the species on this atoll, and the isolation of the east rim of the atoll, the species is recorded in greater densities there than anywhere else in its range (339 crabs/ha).[119]

Mammals

No mammal species are native on Diego Garcia, with no record of bats.[120] Other than rats (Rattus rattus), all "wild" mammal species are feral descendants of domesticated species. During the plantation era, Diego Garcia was home to large herds of Sicilian donkeys (Equus asinus), dozens of horses (Equus caballus), hundreds of dogs (Canis familiaris), and house cats (Felis catus). In 1971, the BIOT Commissioner ordered the extermination of feral dogs following the departure of the last plantation workers, and the program continued through 1975, when the last feral dog was observed and shot.[121] Donkeys, which numbered over 400 in 1972, were down to just 20 individuals in 2005.[122] The last horse was observed in 1995,[122] and by 2005, just two cats were thought to have survived an island-wide eradication program.

Native birds

The total bird list for the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia, consists of 91 species, with large breeding populations of 16 species. Although no birds are endemic, internationally important seabird colonies exist. Diego Garcia's seabird community includes thriving populations of species which are rapidly declining in other parts of the Indian Ocean. Large nesting colonies of brown noddies (Anous stolidous), bridled terns (Sterna anaethetus), the lesser noddy (Anous tenuirostris), red-footed booby (Sula sula) and lesser frigate birds (Fregata ariel), exist on Diego Garcia.

Other nesting native birds include red-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon rubricauda), wedge-tailed shearwaters (Puffinus pacificus), Audubon's shearwater (Puffinus iherminierii), black-naped terns (Sterna sumatrana), white (or fairy) terns (Gygis alba), striated herons (Butorides striatus), and white-breasted waterhens (Amaurornis phoenicurus).[123] The 680-hectare Barton Point Nature Reserve was identified as an Important Bird Area for its large breeding colony of red-footed boobies.[124]

Introduced birds

The island hosts introduced bird species from many regions, including cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis), Indian barred ground dove, also called the zebra dove (Geopelia striata), turtle dove (Nesoenas picturata), Indian mynah (Acridotheres tristis), Madagascar fody (Foudia madagascariensis), and chickens (Gallus gallus).[125]

Terrestrial reptiles and freshwater amphibians

Currently, three lizards and one toad are known to inhabit Diego Garcia, and possibly one snake. All are believed to have been introduced by human activity. The house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus), the mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris), the garden lizard (an agamid) (Calotes versicolor), and the cane toad (Bufo marinus).[126] A viable population of a type of blind snake from the family Typhlopidae may be present, probably the brahminy blind snake (Ramphotyphlops braminus). This snake feeds on the larvae, eggs, and pupae of ants and termites, and is about the size of a large earthworm.

Sea turtles

Diego Garcia provides suitable foraging and nesting habitat for both the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and the green turtle (Chelonia mydas). Juvenile hawksbills are quite common in the lagoon and at Barachois Sylvane (also known as Turtle Cove) in the southern part of the lagoon. Adult hawksbills and greens are common in the surrounding seas and nest regularly on the ocean-side beaches of the atoll. Hawksbills have been observed nesting during June and July, and from November to March. Greens have been observed nesting in every month; the average female lays three clutches per season, each having an average clutch size of 113 eggs. Diurnal nesting is common in both species. An estimated 300–700 hawksbills and 400–800 greens nest in the Chagos.[127]

Endangered species

Four reptiles and six cetaceans are endangered and may or may not be found on or around Diego Garcia:[128] Hawksbill turtle (Eretmocheyls imbricata) – known; leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) – possible; green turtle (Chelonia mydas) – known; olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys oliveacea) – possible; sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) – possible; sei whale (Balaeonoptera borealis) – possible; finback whale (Balaeonoptera physalus) – possible; Bryde's whale (Balaeonoptera edeni) – possible; blue whale (Balaeonoptera musculus) – possible; humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) – possible; southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) – possible.[129]

United Kingdom military activities

British Forces British Indian Ocean Territories (BFBIOT) is the official name for the British Armed Forces deployment at the Permanent Joint Operating Base (PJOB) on Diego Garcia, in the British Indian Ocean Territory.[130] While the naval and airbase facilities on Diego Garcia are leased to the United States, in practice, it operates as a joint UK-US base, with the UK retaining full and continual access.[131] Diego Garcia is strategically located, offering access to East Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The base serves as a staging area for the buildup or resupply of military forces prior to an operation. There are approximately 40–50 British military personnel posted on Diego Garcia, most of them from Naval Party 1002 (NP1002). NP1002 forms the island's civil administration.[132]

United States military activities

During the Cold War era, following the British withdrawal from East of Suez, the United States was keen to establish a military base in the Indian Ocean to counter Soviet influence and establish American dominance in the region and protect its sea-lanes for oil transportation from the Middle East. The United States saw the atoll as the "Malta of the Indian Ocean" equidistant from all points.[133] The value has been proven many times, with the island providing an "unsinkable aircraft carrier" for the United States during the Iranian revolution, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, Operation Desert Fox, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom. In the contemporary era, the atoll continues to play a key role in America's approach to the Indian Ocean as a flexible forward military hub that can facilitate a range of offensive activities.[134][135]

The United States military facilities on Diego Garcia have been known informally as Camp Justice[136][137][138] and, after renaming in July 2006, as Camp Thunder Cove.[139] Formally, the base is known as Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia (the US activity) or Permanent Joint Operating Base (PJOB) Diego Garcia (the UK's term).[140]

United States military activities in Diego Garcia have caused friction between India and the United States in the past.[141] Political party CPI(m) in India has[142] repeatedly called for the military base to be dismantled, as they saw the United States naval presence in Diego Garcia as a hindrance to peace in the Indian Ocean.[142] In recent years, relations between India and the United States have improved dramatically. Diego Garcia was the site of several naval exercises between the United States and Indian navies held between 2001 and 2004.[143][144]

Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia

Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia provides Base Operating Services to tenant commands located on the island. The command's mission is "To provide logistic support to operational forces forward deployed to the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf AORs in support of national policy objectives."[145]

United States Air Force units based on Diego Garcia

- 36 MSG, Pacific Air Force

- Det 1, 730th Air Mobility Squadron, Air Mobility Command

- Det 1, 21st Space Operations Squadron, an Air Force Satellite Control Network Remote Tracking Station, Space Operations Command

- Det 2, a GEODSS facility, Space Operations Command

United States pre-positioned vessels

The atoll shelters the ships of the United States Marine Pre-positioning Squadron Two. These ships carry equipment and supplies to support a major armed force with tanks, armoured personnel carriers, munitions, fuel, spare parts and even a mobile field hospital. This equipment was used during the Persian Gulf War, when the squadron transported equipment to Saudi Arabia.

The ship composition of MPSRON TWO is dynamic. During August 2010 it was composed of the following:

- MV Capt. Steven L. Bennett

- USNS SGT William R. Button (T-AK-3012),[146]

- MV SSG Edward A. Carter, Jr. (T-AK-4544),[147]

- MV Maj. Bernard F. Fisher

- USNS Lawrence H. Gianella

- USNS SGT Matej Kocak (T-AK-3005),[148]

- USNS 1st LT Baldomero Lopez (T-AK-3010),[149]

- MV LTC John U. D. Page[150]

- USNS GYSGT Fred W. Stockham

Five of these vessels carry supplies for the US Marine Corps sufficient to support a Marine Air-Ground Task Force for 30 days: USNS Button, USNS Kocak, USNS Lopez, USNS Stockham, and USNS Fisher.

Prior to 2001, COMPSRON 2 consisted of up to 20 ships, including four Combat Force Ships which provided rapid-response delivery of equipment to ground troops in the United States Army. Three are lighter aboard ships (LASH) which carry barges called lighters that contain Army ammunition to be ferried ashore: MV American Cormorant, SS Green Harbour, (LASH), SS Green Valley, (LASH), MV Jeb Stuart, (LASH). There were logistics vessels to service the rapid delivery requirements of the United States Air Force, United States Navy and Defense Logistics Agency. These included container ships for Air Force munitions, missiles and spare parts; a 500-bed hospital ship, and floating storage and offloading units assigned to Military Sealift Command supporting the Defense Logistics Agency, and an offshore petroleum discharge system (OPDS) tanker. Examples of ships are MV Buffalo Soldier, MV Green Ridge, pre-position tanker USNS Henry J. Kaiser, and tanker USNS Potomac (T-AO-181).

HF global station

The United States Air Force operates a High Frequency Global Communications System transceiver site located on the south end of the atoll near the GEODSS station. The transceiver is operated remotely from Andrews Air Force Base and Grand Forks Air Force Base and is locally maintained by NCTS FE personnel.[151][152]

Naval Computer and Telecommunications Station Far East Detachment Diego Garcia

Naval Computer and Telecommunications Station Far East Detachment Diego Garcia operates a detachment in Diego Garcia. This detachment provides base telephone communications, base network services (Local Network Services Center), pier connectivity services, and an AN/GSC-39C SHF satellite terminal, operates the Hydroacoustic Data Acquisition System, and performs on-site maintenance for the remotely operated Air Force HF-GCS terminal.

Naval Security Group Detachment Diego Garcia

Naval Security Group detachment Diego Garcia was disestablished on 30 September 2005.[153] Remaining essential operations were transferred to a contractor. The large AN/AX-16 High Frequency Radio direction finding Circularly Disposed Antenna Array has been demolished, but the four satellite antenna radomes around the site remain as of 2010.

ETOPS emergency landing site

Diego Garcia may be identified as an ETOPS (Extended Range Twin Engine Operations) emergency landing site (en route alternate) for flight planning purposes of commercial airliners. This allows twin-engine commercial aircraft (such as the Airbus A330, Boeing 767 or Boeing 777) to make theoretical nonstop flights between city pairs such as Perth and Dubai (9,013.61 km or 5,600.80 mi), Hong Kong and Johannesburg (10,658 km or 6,623 mi) or Singapore and São Paulo (15,985.41 km or 9,932.87 mi), all while maintaining a suitable diversion airport within 180 minutes' flying time with one engine inoperable.[154]

Space Shuttle

The island was one of 33 designated emergency landing sites worldwide for the NASA Space Shuttle.[155] None of these facilities were ever used throughout the life of the shuttle program.

Cargo service

All consumable food and equipment are brought to Diego Garcia by sea or air, and all non-biodegradable waste is shipped off the island as well. From 1971 to 1973, United States Navy LSTs provided this service. Beginning in 1973, civilian ships were contracted to provide these services. From 2004 to 2009, the US-flagged container ship MV Baffin Strait, often referred to as the "DGAR shuttle," delivered 250 containers every month from Singapore to Diego Garcia.[156] The ship delivered "more than 200,000 tons of cargo to the island each year."[156] On the return trip to Singapore, it carried recyclable metals.[157]

In 2004, TransAtlantic Lines outbid Sealift Incorporated for the transport contract between Singapore and Diego Garcia.[158] The route had previously been serviced by Sealift Inc.'s MV Sagamore, manned by members of American Maritime Officers and Seafarers' International Union.[158] TransAtlantic Lines reportedly won the contract by approximately 10 percent, representing a price difference of about US$2.7 million.[158] The Baffin Straits charter ran from 10 January 2005, to 30 September 2008, at a daily rate of US$12,550.

References

- "Country Profile: British Indian Ocean Territory (British Overseas Territory)". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Diego Garcia". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Chagos Islanders v Attorney General Her Majesty's British Indian Ocean Territory Commissioner [2003] EWHC 2222 (QB) (9 October 2003), High Court (England and Wales)

- R (on the application of Bancoult) v. Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2006] EWHC 1038 (Admin) (11 May 2006), High Court (Admin)

- Bengali, Shashank (14 August 2018). "A half-century after being uprooted for a remote U.S. Naval base, these islanders are still fighting to return". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Andersen AFB".

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "World Time Chart" (PDF). US Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Sengupta, Somini (22 June 2017). "U.N. Asks International Court to Weigh in on Britain-Mauritius Dispute". The New York Times.

- "Chagos legal status sent to international court by UN". BBC News. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Chagos Islands dispute: UK obliged to end control – UN". BBC News. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "UK suffers crushing defeat in UN vote on Chagos Islands". The Guardian. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 22 May 2019". UN General Assembly. 22 May 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Joshua Karsten (7 March 2019). "UN ruling raises questions about future of US mission in Diego Garcia". Stars and Stripes.

- Burgess, Richard R. (24 June 2020). "Navy Base in Diego Garcia Welcome to Stay After Transfer of Sovereignty, Official Says". Seapower Magazine. Navy League of the United States. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

The U.S. Navy base in Diego Garcia, an outpost in the Chagos archipelago in the Indian Ocean, would be welcome to remain if Mauritius succeeds in its sovereignty claim over the archipelago, currently known as the British Indian Ocean Territories (BIOT), a Mauritian official said.

- Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5. Chapter 1 "A Seafaring Nation", page 19

- Josmael Bardour. "PORTUGAL MARÍTIMO: Abril 2011". jmbd1945.blogspot.pt.

- "The Diego Garcia Test Question". zianet.com.

- "History of Diego Garcia Atoll, Indian Ocean". zianet.com.

- Edith Porchat (1956). Informações históricas sobre São Paulo no século de sua fundação. Editora Iluminuras Ltda. p. 61. ISBN 978-85-85219-75-8.

- Edis (2004), p. 29.

- Edis (2004), p. 32.

- Edis (2004), p. 33.

- Edis (2004), p. 80.

- D. R. Stoddart (1971): "Settlement and development of Diego Garcia". In: Stoddart & Taylor (1971), pp. 209–218.

- Mücke, Hellmuth von (1916). Helmuth von Mucke 'The Emden'. p. 130.

- subiepowa (28 April 2007). "Cannon Point, Diego Garcia" – via YouTube.

- Edis (2004), p. 73.

- Edis (2004), p. 70.

- Edis (2004), p. 82.

- Sand (2009), p. 3.

- Chagos Islanders v Attorney General and Her Majesty's British Indian Ocean Territory Commissioner [2003] EWHC 2222 (QB) (9 October 2003)

- "Report: The use of Diego Garcia by the United States". US Parliament, September 2014

- Sand (2009), pp. 6–8.

- African Research Group (2000). Health & Mortality in the Chagos Islands (PDF). Research and Analytical Papers. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- David Vine. "Island of Injustice". The Washington Post.

- "Pilger reveals: British-US conspiracy to steal a nation". Green Left Weekly. 3 November 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Ted Morris. "Personal Accounts of Landing on Diego Garcia, 1971". Zianet.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Sand (2009), p. 24.

- Sand (2009), p. 25.

- Edis (2004), p. 88.

- Edis (2004), p. 90.

- Owen Bowcott; Sam Jones (19 March 2015). "UN ruling raises hope of return for exiled Chagos islanders". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom) (Press Release and Summary of Award)". Permanent Court of Arbitration. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Slavery in the Chagos Archipelago" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Edis (2004), pp. 49–54.

- "England and Wales High Court of Justice, Queens Bench Division Appendix, Paragraph 396". Hmcourts-service.gov.uk. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "England and Wales High Court of Justice, Queens Bench Division Appendix, Paragraph 417". Hmcourts-service.gov.uk. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Paragraph 629". Uniset.ca. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "European Union – EEAS (European External Action Service)". europa.eu. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010.

- Owen Bowcott (27 September 2010). "Chagos Islands exiles amazed by speed of Foreign Office's opposition to seabed claim by Maldives". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Ted A. Morris, Jr. "See email claims from John Bridiane". Zianet.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- John Pike (3 February 2002). "Air Force looking into salvaging parts of B-1B bomber that crashed off". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- David Vine, (2009) Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia, Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 6.

- Sheppard & Spalding (2003), p. 28.

- Early day motion 1680 UK Parliament, 16 September 2004

- Edis (2004), p. 84.

- Edis (2004), p. 89.

- CIA World Factbook, accessed 23 August 2010.

- "Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones at a Glance". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 9 August 2006. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- Sand, Peter H. (29 January 2009), "Diego Garcia: British–American Legal Black Hole in the Indian Ocean?", Journal of Environmental Law, Oxford Journals, 21 (1), pp. 113–137, doi:10.1093/jel/eqn034

- "Info" (PDF). issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Noel Stott (2011). "The Treaty of Pelindaba: towards the full implementation of the African NWFZ Treaty" (PDF). Disarmament Forum: 20–21. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Denied Entry: Israel Blocks Noam Chomsky from Entering West Bank to Deliver Speech". democracynow.org.

- "African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Force: What Next for Diego Garcia? | ASIL".

- Mauritius to reiterate its conditions for renewed talks with UK on Chagos Archived 23 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine at afriqueavenir.org

- Catherine Philp (6 March 2010). "Chagossians fight for a home in paradise". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Ian Cobain (30 January 2015). "CIA interrogated suspects on Diego Garcia, says Colin Powell aide". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- "Terror suspects were interrogated on Diego Garcia, US official admits". Daily Telegraph. Press Association. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- "Written Answers to Questions 21 June 2004" (– Scholar search). Hansard House of Commons Daily Debates. 422 (part 605). Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- Lynda Hurst (2 July 2005). "Island paradise or torture chamber?". The Toronto Star. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Andrew Selsky (16 March 2006). "Detainee transcripts reveal more questions". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Ian Cobain; Richard Norton-Taylor (19 October 2007). "Claims of secret CIA jail for terror suspects on British island to be investigated". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- Zagorin, Adam (31 July 2008). "Source: US Used UK Isle for Interrogations". Time. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Cobain, Ian; Richard Norton-Taylor (19 October 2007). "Claims of secret CIA jail for terror suspects on British island to be investigated". The Guardian.

- Jamie Doward (2 March 2008). "British island 'used by US for rendition'". The Observer. London. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- Dick Marty, Switzerland, ALDE (7 June 2007). "Secret detentions and illegal transfers of detainees involving Council of Europe member states: second report" (PDF). Section 70; page 13. Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights. Retrieved 21 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Staff writers (21 February 2008). "UK apology over rendition flights". BBC News. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- "WikiLeaks, a forgotten people, and the record-breaking marine reserve, Posted by Sean Carey – 8 December 2010". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Cable Viewer". Wikileaks.ch. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Sheppard & Spalding (2003), chapter 6.

- "Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands: Chagos Banks" (PDF). United Kingdom Overseas Territories Conservation Forum. 13 November 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 2.4.1.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 2.5.1.

- "Science of the Chagos – Chagos Conservation Trust". Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Important Dates of the Provisional People's Democratic Republic of Diego Garcia". 29 August 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Chagos News, No. 25, p. 2 Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Local Area Forecaster's Handbook (2002), p. 13.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 2.5.2.

- "Salt Water vs. Fresh Water – Ghyben-Herzberg Lens". Geography.about.com. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Urish (1974), p. 27.

- Urish (1974), p. 28.

- Charles D. Hunt "Hydrogeology of Diego Garcia". In: Vacher & Quinn (1997), pp. 909–929. doi:10.1016/S0070-4571(04)80054-2.

- D. R. Stoddart (1971): "Land vegetation of Diego Garcia". In: Stoddart & Taylor (1971), pp. 127–142.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 3.3.2.1.

- Stephen W. Surface and Edward F.C. Lau, "Fresh Water Supply System Developed on Diego Garcia", The Naval Civil Engineer, Winter 1985

- Local Area Forecaster's Handbook (2002), p. 14.

- Edis (2004), p. 71.

- Ted Morris (19 September 2002). "Diego Garcia – The PBY Catalina". Zianet.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Diego Garcia Navy base reports no damage from quake, tsunamis" Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Leo Shane III, Stars and Stripes. 28 December 2004. URL accessed 1 June 2006.

- Sheppard, Charles (April 2005). "The Tsunami, Shore Erosion and Corals in the Chagos Islands" (PDF). Chagos News. 25: 2–7. ISSN 1355-6746. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- "Klimatafel von Diego Garcia, Chagos-Archipel / Indischer Ozean / Großbritannien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Station Diego Garcia" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix E1, p. 1.

- Stoddart & Taylor (1971)

- Topp (1988), p. 2.

- Hamilton & Topp (2009)

- F. R. Fosberg & A. A. Bullock (1971): "List of Diego Garcia vascular plants". In: Stoddart & Taylor (1971), pp. 143–160.

- Sheppard & Seaward (1999), p. 225.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix E2, paragraph E2-2.

- Sheppard & Spalding (2003), p. 40.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix E1, p. 4-3.

- "Neisosperma oppositifolium (Lam.) Fosberg & Sachet". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix E1, p. 4-5.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix E1, p. 4-6.

- President for Life. "Aerial Photographs of Diego Garcia". Zianet.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix B.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix G, p. G-7.

- D. R. Stoddart (1971): "Terrestrial fauna of Diego Garcia and other Chagos atolls". In: Stoddart & Taylor (1971), pp. 163–170.

- Bruner, Phillip, Avifaunal and Feral Mammal Survey of Diego Garcia, Chagos Archipelago, British Indian Ocean Territory, 17 October 1995, p. 3-23.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix G, p. 4.27.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 4.2.2.1.1.

- "Barton Point Nature Reserve". Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2012. Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 4.2.2.1.3.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 4.2.2.6.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), Appendix K, pp. K-2–K-3.

- Natural Resources Management Plan (2005), paragraph 4.4.

- Carroll L.E.. 2011. Return of the Right Whale: Assessment of Abundance, Population Structure and Geneflow in the New Zealand Southern Right Whale. University of Auckland. Retrieved on 25 November 2015

- Permanent Joint Operating Bases (PJOBs), www.gov.uk, 12 December 2012

- "The Status and Location of the Military Installations of the Member States of the European Union" (PDF). Policy Department External Policies: 13–14. February 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Welcome to Diego Garcia Archived 5 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, page 3, DIEGO GARCIA, A BRITISH TERRITORY, public.navy.mil

- Ladwig, Erickson and Mikolay (2014), pp. 138–42.

- Walter C. Ladwig III "A Neo-Nixon Doctrine for the Indian Ocean: Helping States Help Themselves" (PDF). Strategic Analysis. May 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- James R. Holmes & Toshi YoshiharaHolmes, James R; Yoshihara, Toshi (March 2012). "An Ocean Too Far: Offshore Balancing in the Indian Ocean". Asian Security. 8 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/14799855.2011.652025. S2CID 153355074.

- Jeffrey Fretland (4 December 2003). "Liberty Hall One Step Closer to a Cool Summer". United States Navy. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Jeremy L. Wood (30 December 2002). "Comedian Visits Troops on Remote Isle". United States Navy. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- "United States Navy Diego Garcia Support Facility". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Jason Smith (26 July 2006). "'Camp Justice' Becomes 'Thunder Cove': Airmen of 40th Air Expeditionary Group give tent city a new name". United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Ladwig, Erickson and Mikolay (2014), pp. 141–3.

- Ladwig, Erickson and Mikolay (2014), pp. 155.

- Yechury, Sitaram (1 July 2001). "Access to Indian Military Bases: Making India an Appendage to US". People's Democracy. XXV (26). Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- Ladwig, Erickson and Mikolay (2014), pp. 156.

- "Mauritius may relent on US base in Diego Garcia". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 13 April 2002.

- About Navy Support Facility Diego Garcia retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "USNS SGT WILLIAM R. BUTTON (T-AK 3012)". Ship Inventory. Military Sealift Command. 16 January 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2011.