Atoll

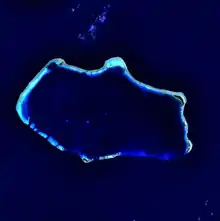

An atoll ( /ˈætɒl, ˈætɔːl, ˈætoʊl, əˈtɒl, əˈtɔːl, əˈtoʊl/),[1][2] sometimes known as a coral atoll, is a ring-shaped coral reef, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim.[3] (p60)[4]

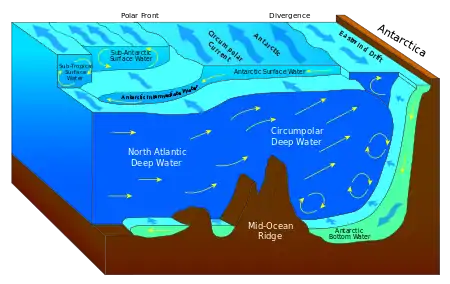

The typical atoll is originally formed as an oceanic volcano. A coral reef will grow around the shore of the volcano and then, over several million years, the volcano becomes extinct, eroded and subsided completely beneath the surface of the ocean. The reef and the small coral islets on top of it are all that is left of the original island, and a lagoon has taken the place of the former volcano. For the atoll to persist, the coral reef must be maintained at the sea surface, with coral growth matching any relative change in sea level (subsidence of the island or rising oceans).[5]

Usage

The word atoll comes from the Dhivehi (an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Maldives) word atholhu (Dhivehi: އަތޮޅު, [ˈət̪ɔɭu]), meaning the palm (of the hand).OED Its first recorded use in English was in 1625 as atollon. Charles Darwin recognized its indigenous origin and coined the definition of atolls as "circular groups of coral islets", which is synonymous with "lagoon-island", in his The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs.[6](p2)

More modern definitions of atoll describe them as "annular reefs enclosing a lagoon in which there are no promontories other than reefs and islets composed of reef detritus"[7] or "in an exclusively morphological sense, [as] a ring-shaped ribbon reef enclosing a lagoon".[8]

Distribution and size

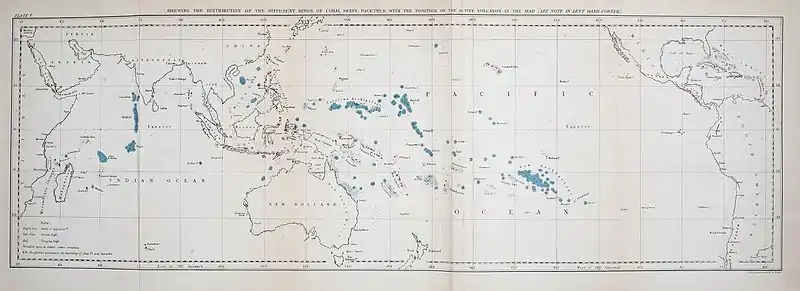

There are approximately 440 atolls in the world.[10]

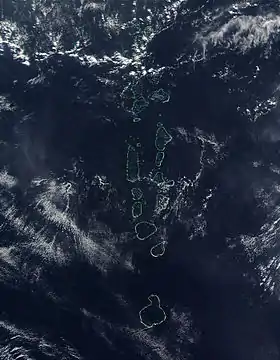

Most of the world's atolls are in the Pacific Ocean (with concentrations in the Caroline Islands, the Coral Sea Islands, the Marshall Islands, the Tuamotu Islands, and the island groups of Kiribati, Tokelau, and Tuvalu) and the Indian Ocean (the Chagos Archipelago, Lakshadweep, the atolls of the Maldives, and the Outer Islands of Seychelles). The Atlantic Ocean has no large groups of atolls, other than eight atolls east of Nicaragua that belong to the Colombian department of San Andres and Providencia in the Caribbean.

Reef-building corals will thrive only in warm tropical and subtropical waters of oceans and seas, and therefore atolls are found only in the tropics and subtropics. The northernmost atoll of the world is Kure Atoll at 28°24′ N, along with other atolls of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The southernmost atolls of the world are Elizabeth Reef at 29°58′ S, and nearby Middleton Reef at 29°29′ S, in the Tasman Sea, both of which are part of the Coral Sea Islands Territory. The next southerly atoll is Ducie Island in the Pitcairn Islands Group, at 24°40′ S.

Bermuda is sometimes claimed as the "northernmost atoll" at a latitude of 32°24′ N. At this latitude, coral reefs would not develop without the warming waters of the Gulf Stream. However, Bermuda is termed a pseudo-atoll because its general form, while resembling that of an atoll, has a very different mode of formation. While there is no atoll directly on the Equator, the closest atoll to the Equator is Aranuka of Kiribati, with its southern tip just 12 km (7 miles) north of the Equator.

In most cases, the land area of an atoll is very small in comparison to the total area. Atoll islands are low lying, with their elevations less than 5 meters (16'). Measured by total area, Lifou (1146 km2; 442 sq. mi.) is the largest raised coral atoll of the world, followed by Rennell Island (660 km2; 255 sq. mi.).[13] More sources, however, list Kiritimati as the largest atoll in the world in terms of land area. It is also a raised coral atoll (321.37 km2; 125 sq. mi. land area; according to other sources even 575 km2; 2220 sq. mi.), 160 km2 (62 sq. mi.) main lagoon, 168 km2 (65 sq. mi.) other lagoons (according to other sources 319 km2 total lagoon size; 123 sq. mi.).

The remains of an ancient atoll as a hill in a limestone area is called a reef knoll. The second largest atoll by dry land area is Aldabra, with 155 km2 (60 sq. mi.). The largest atoll in terms of island numbers is Huvadhu Atoll in the south of the Maldives, with 255 islands.

Formation

.jpg.webp)

In 1842, Charles Darwin explained the creation of coral atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean based upon observations made during a five-year voyage aboard HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836. Accepted as basically correct, his explanation suggested that several tropical island types: from high volcanic island, through barrier reef island, to atoll, represented a sequence of gradual subsidence of what started as an oceanic volcano. He reasoned that a fringing coral reef surrounding a volcanic island in the tropical sea will grow upward as the island subsides (sinks), becoming an "almost atoll", or barrier reef island, as typified by an island such as Aitutaki in the Cook Islands, and Bora Bora and others in the Society Islands. The fringing reef becomes a barrier reef for the reason that the outer part of the reef maintains itself near sea level through biotic growth, while the inner part of the reef falls behind, becoming a lagoon because conditions are less favorable for the coral and calcareous algae responsible for most reef growth. In time, subsidence carries the old volcano below the ocean surface and the barrier reef remains. At this point, the island has become an atoll.

Atolls are the product of the growth of tropical marine organisms, and so these islands are found only in warm tropical waters. Volcanic islands located beyond the warm water temperature requirements of hermatypic (reef-building) organisms become seamounts as they subside, and are eroded away at the surface. An island that is located where the ocean water temperatures are just sufficiently warm for upward reef growth to keep pace with the rate of subsidence is said to be at the Darwin Point. Islands in colder, more polar regions evolve toward seamounts or guyots; warmer, more equatorial islands evolve toward atolls, for example Kure Atoll.

Darwin's theory starts with a volcanic island which becomes extinct

Darwin's theory starts with a volcanic island which becomes extinct As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a fringing reef, often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef

As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a fringing reef, often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef As the subsidence continues the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef farther from the shore with a bigger and deeper lagoon inside

As the subsidence continues the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef farther from the shore with a bigger and deeper lagoon inside Ultimately the island sinks below the sea, and the barrier reef becomes an atoll enclosing an open lagoon

Ultimately the island sinks below the sea, and the barrier reef becomes an atoll enclosing an open lagoon

Reginald Aldworth Daly offered a somewhat different explanation for atoll formation: islands worn away by erosion, by ocean waves and streams, during the last glacial stand of the sea of some 900 feet (270 m) below present sea level developed as coral islands (atolls), or barrier reefs on a platform surrounding a volcanic island not completely worn away, as sea levels gradually rose from melting of the glaciers. Discovery of the great depth of the volcanic remnant beneath many atolls, such as at Midway Atoll, favors the Darwin explanation. But fluctuating sea level has also had considerable influence on atolls and other reefs.

Coral atolls are important as places where dolomitization of calcite occurs. At certain depths water is undersaturated in calcium carbonate but saturated in dolomite. Convection created by tides and sea currents enhances this change. Hydrothermal currents created by volcanoes under the atoll may also play an important role.

Investigation by the Royal Society of London into the formation of coral reefs

In 1896, 1897 and 1898, the Royal Society of London carried out drilling on Funafuti atoll in Tuvalu for the purpose of investigating the formation of coral reefs. They wanted to determine whether traces of shallow water organisms could be found at depth in the coral of Pacific atolls. This investigation followed the work on the structure and distribution of coral reefs conducted by Charles Darwin in the Pacific.

The first expedition in 1896 was led by Professor William Johnson Sollas of the University of Oxford. Geologists included Walter George Woolnough and Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney. Professor Edgeworth David led the expedition in 1897.[14] The third expedition in 1898 was led by Alfred Edmund Finckh.[15][16][17]

United States national monuments

On January 6, 2009, U.S. President George W. Bush announced the creation of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, covering several islands and atolls under U.S. jurisdiction.[18][19](Number 1, page 14)

See also

Islands portal

Islands portal- Low island

- Nukuoro Atoll

- Kapingamarangi Atoll

References

- pronunciation in old video on youtube, Bikini Atoll video

- "atoll". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Blake, Gerald Henry, ed. (1994). World Boundary Series. 5 Maritime Boundaries. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08835-0. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Migoń, Piotr, ed. (2010). Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer. p. 349. ISBN 978-90-481-3055-9. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Erickson, Jon (2003). Marine Geology: Exploring the New Frontiers of the Ocean. Facts on File, Inc. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-0-8160-4874-8.

- Darwin, Charles R (1842). The structure and distribution of coral reefs. Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836. Darwin Online. London: Smith Elder and Co.

- McNeil (1954, p. 396).

- Fairbridge (1950, p. 341).

- "Archipiélago de Los Roques" (in Spanish). Caracas, Venezuela: Instituto Nacional de Parques (INPARQUES). 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Watts, T. (2019). "Science, Seamounts and Society". Geoscientist. August 2019: 10–16.

- "Atoll Area, Depth and Rainfall" (spreadsheet). The Geological Society of America. 2001.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Misinformation about Islands". worldislandinfo.com.

- David, Cara (Caroline Martha) (1899). Funafuti or Three Months On A Coral Atoll: an unscientific account of a scientific expedition. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-151-25616-4.

- Finckh, Dr. Alfred Edmund (11 September 1934). "TO THE EDITOR OF THE HERALD". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW: National Library of Australia. p. 6. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Cantrell, Carol (1996). "Finckh, Alfred Edmund (1866–1961)". Australian Dictionary of Biography at Australian National University. National Centre of Biography. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Rodgers, K A; Cantrell, Carol (1987). "Alfred Edmund Finckh 1866–1961: Leader of the 1898 Coral Reef Boring Expedition to Funafuti". Historical Records of Australian Science. 7 (4): 393–403. doi:10.1071/HR9890740393. PMID 11617111.

- "Presidential Proclamation 8336" (PDF). The White House. 6 January 2009.

- "Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents" (PDF). 12 January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2009.

- Dobbs, David. 2005. Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral. Pantheon. ISBN 0-375-42161-0

- Fairbridge, R. W. 1950. "Recent and Pleistocene coral reefs of Australia". J. Geol., 58(4): 330–401.

- McNeil, F. S. 1954. "Organic reefs and banks and associated detrital sediments". Amer. J. Sci., 252(7): 385–401.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atoll. |

- Formation of Bermuda reefs

- Darwin's Volcano – a short video discussing Darwin and Agassiz' coral reef formation debate

- NOAA National Ocean Service Education - Coral Atoll Animation

- NOAA National Ocean Service - What are the three main types of coral reefs?

- Research Article: Predicting Coral Recruitment in Palau’s Complex Reef Archipelago

- World Atolls, Goldberg 2016: A global map containing all atolls