Dutch–Portuguese War

The Dutch–Portuguese War was an armed conflict involving Dutch forces, in the form of the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, against the Portuguese Empire. Beginning in 1602, the conflict primarily involved the Dutch companies invading Portuguese colonies in the Americas, Africa, India, and the Far East. The war can be thought of as an extension of the Eighty Years' War being fought in Europe at the time between Spain and the Netherlands, as Portugal was in a dynastic union with the Spanish Crown after the War of the Portuguese Succession, for most of the conflict. However, the conflict had little to do with the war in Europe and served mainly as a way for the Dutch to gain an overseas empire and control trade at the cost of the Portuguese. English forces also assisted the Dutch at certain points in the war (though in later decades, English and Dutch would become fierce rivals). Because of the commodity at the center of the conflict, this war would be nicknamed the Spice War.

| Dutch–Portuguese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

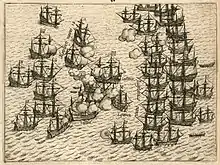

Portuguese galleon fighting Dutch and English warships | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: (until 1640) Kingdom of Cochin Potiguara Tupis Kingdom of Hormuz Ming China |

Supported by: (until 1640) Kingdom of Ndongo Rio Grande Tupis Nhandui Tarairiu Tribe | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The outcome was that Portugal successfully repelled Dutch attempts to secure Brazil and Angola while the Dutch were the victors in the Cape of Good Hope and the East Indies, with the exception of Macau which the Portuguese retained, capturing Malacca, Ceylon, the Malabar Coast, and the Moluccas. English ambitions also greatly benefited from the long-standing war between their two main rivals in the Far East (beginning in the late 18th to early 19th century Malacca, Ceylon, and Malabar would become British possessions).

Portuguese resentment at Spain, which was perceived as having prioritized its own colonies and neglected the defense of the Portuguese ones, was a major contributing factor to Portugal shaking off Spanish rule in the Portuguese Restoration War, conducted simultaneously with the later stages of the war with the Dutch.

Introduction

The war lasted from 1602 to 1663, and the main participants were the Kingdom of Portugal and the Republic of the Seven United Provinces.

Following the 1580 Iberian Union, Portugal was throughout most of the period under Habsburg rule, and the Habsburg Philip II of Spain was battling the Dutch Revolt. Prior to the union of the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns, Portuguese merchants used the Low Countries as a base for the sale of their spices in northern Europe. After the Spaniards gained control of the Portuguese Empire though, they declared an embargo on all trade with the rebellious provinces (see Union of Utrecht). In his efforts to subdue the rebelling provinces, Philip II cut off the Netherlands from the spice markets of Lisbon, making it necessary for the Dutch to send their own expeditions to the sources of these commodities and to take control of the Indies spice trade.

Like the French and English, the Dutch worked to create a global trade network at the expense of the Iberian kingdoms. The Dutch Empire attacked many territories in Asia under the rule of the Portuguese and Spanish including Formosa, Ceylon, the Philippine Islands, and commercial interests in Japan, Africa (Mina), and South America.

Background

In 1592, during the war with Spain, an English fleet had captured a large Portuguese galleon off the Azores, the Madre de Deus, loaded with 900 tons of merchandise from India and China, worth an estimated half a million pounds (nearly half the size of English Treasury at the time).[1] This foretaste of the riches of the East galvanized interest in the region.[2] That same year, Dutch merchants sent Cornelis de Houtman to Lisbon, to gather as much information as he could about the Spice Islands. In 1595, merchant and explorer Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, having traveled widely in the Indian Ocean in the service of the Portuguese, published a travel report in Amsterdam, the "Reys-gheschrift vande navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten" ("Report of a journey through the navigations of the Portuguese in the East").[3] The published report included vast directions on how to navigate ships between Portugal and the East Indies and to Japan. Dutch and British interest fed by new information led to a movement of commercial expansion, and the foundation of the English East India Company in 1600, and Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602, allowing the entry of chartered companies in the so-called East Indies.

In 1602, the VOC was founded, with the goal of sharing the costs of the exploration of the East Indies and ultimately re-establishing the spice trade, a vital source of income to the new Republic of the Seven United Provinces.

The need of founding the VOC arose because, with the war with Spain and Portugal being united to Spain, the trade would now be directed through the southern low countries (roughly present-day Belgium), which according to the Union of Arras (or Union of Atrecht) were pledged to the Spanish monarch and were Roman Catholic, as opposed to the Dutch Protestant north. This also meant that the Dutch had lost their most profitable trade partner and their most important source of financing the war against Spain. Additionally, the Dutch would lose their distribution monopoly with France, the Holy Roman Empire, and northern Europe. Their North Sea fishing and Baltic cereal trading activities would simply not suffice to maintain the republic.

The Portuguese Empire in the Indian Ocean was a traditional thalassocracy that had extended its reach to every major choke point in the ocean. Trade in the area corresponded also to a traditional triangular model whereupon small manufactures would be brought from Europe and traded in Africa for gold and several items, then these would serve to purchase spices in India proper which were then brought back to Europe and traded at immense profit which would be reinvested into ships and troops, to be sent eastwards.

The Portuguese State of India, headquartered in Goa, was a network of key cities which controlled the maritime trade in the Indian Ocean: Sofala was the base for Portuguese operations in East Africa and was supported by Kilwa to better control the Mozambique Channel; from here, the routes took the trade to Goa which was the hub for the rest of the operations and where the India Convoy ships out of Europe arrived; from Goa, going northwards, the trade would be protected by the North and Adventurers Fleets all the way to Daman and Diu which oversaw the northern trade and the Gulf of Cambay; while the Fleet of the North escorted merchant ships the Adventurers Fleet would also seek to disrupt the Mecca trade between northern India's Muslims and the Arabian Peninsula; the Diu Fleet would then connect the trade to Hormuz which controlled the Persian Gulf routes and interrupted the Basrah-Suez trade; southwards from Goa, the Cape Comorin Fleet would escort the Goa merchants to Calicut and Cochin on the Malabar Coast and to Ceylon and the connection to the Bay of Bengal; in the Bay of Bengal, the most lucrative trade was on the Coromandel Coast where such settlements as São Tomé of Mylapore and Pulicat served as hubs; it was in the Coromandel and Ceylon settlements where the ships out of the Malacca route often laid anchor because they connected the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea; the Malacca Fleet patrolled the Singapore Strait and the routes diverted to Celebes and what is now Indonesia at large in the south, and northwards to China and Japan; China provided silk and china to Macau from where the 'Silver Carrack' connected to Japan where several products were exchanged for Japanese silver.[4]

Casus belli

At dawn on February 25, 1603, three ships of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) seized the Santa Catarina, a Portuguese galleon. It was such a rich prize that its sale proceeds doubled the capital of the VOC. The legality of keeping the prize was questionable under Dutch statute and the Portuguese demanded the return of their cargo. The scandal led to a public judicial hearing and a wider campaign to sway public (and international) opinion. As a result, Hugo Grotius in The Free Sea (Mare Liberum, published 1609) formulated the new principle that the sea was international territory, against the Portuguese mare clausum policy, and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. The 'free seas' provided suitable ideological justification for the Dutch to break the Portuguese monopoly through its formidable naval power.

Insertion in the East: Batavia challenges Goa

Portugal's Indian Ocean empire relied on three strategic bases: Goa, Malacca, and Macau. The first connected the State of India with Portugal proper, the second connected Goa to the Pacific Ocean trade stretching from the China seas to Australasia, and the third was the hub for the trade with China and Japan. Two other cities were important but not crucial: Diu and Hormuz. Diu controlled the Gulf of Cambay and the Arabian Sea approaches and Hormuz was the keystone of the Persian Gulf trade, both between Persia and Arabia and between Mesopotamia and the Arabian Sea. If both Diu and Hormuz fell, that would prevent the Middle East markets from being taxed by Portugal which would deny Lisbon the revenue from the southernmost course of the Silk Route. This was a lucrative trade but not as essential to the Indian Ocean network at large. After the fall of Hormuz to the English and Dutch, the Portuguese striking out of their Muscat and Goa bases, led a destructive campaign against Persia's coastline and allied with the Basrah Ottomans. Eventually, after the Battle of the three islands Persia vied for a cease-fire with the Portuguese to be able to reestablish trade and provided Portugal with a tradepost in Kong. Together with the reestablished Basrah route, this temporarily made up for the loss of Hormuz. The pioneers of the destruction of the Portuguese and Spanish mare clausum doctrine were the Dutch.

The Dutch East India Company, however, suffered from the same weakness as Portugal: lack of manpower. Thus, a Spanish style colonisation effort was never feasible and only dominion of the seas would allow it to compete. The Portuguese had a century head-start in the region and their empire allowed them access to converted and loyal local populations, which shored-up inland, what naval power could not ensure at sea. Hence, the Dutch directed their efforts to the periphery of the Portuguese empire. Avoiding the Indian coasts, they set up their own headquarters in the southeast Indies, in the city of Jakarta, later known as Batavia. This put them safely distant from Goa but opportunistically close to Malacca and the Indian Ocean – Pacific Ocean-connecting sea lanes. Many battles were fought but the most decisive ones fatally injured the Portuguese Indian empire. The Dutch Blockade of Goa between 1604 and 1645 deprived the State of India from a safe connection to Lisbon – and Europe – for the remainder of the war.

The Battle of Carracks Island in 1615 off the coast of Malacca, destroyed Portuguese naval power in the Southeast Indies leading to the loss of naval supremacy to the Dutch, in the crucial route between Goa and Macau. The Battle of Hormuz in 1621/2 against the English East India Company resulted in the loss of the fortress of Hormuz to the combined forces of Persia and England which dislodged the Portuguese from the Middle East. The 1639 expulsion of the Jesuit order (Sakoku) and subsequently the Portuguese, from Nagasaki, also doomed the economic viability of Macau. The Siege of Malacca of 1641, after many attempts, delivered the city to the Dutch and their regional allies, crucially breaking the spinal cord between Goa and the Orient.[4]

Portuguese establishments were isolated and prone to being picked off one by one, but nevertheless the Dutch only enjoyed mixed success in doing so.[5] Amboina was captured from the Portuguese in 1605, but an attack on Malacca, the Battle of Cape Rachado, the following year narrowly failed in its objective to provide a more strategically located base in the East Indies with favorable monsoon winds.[6] In 1607 and 1608, the Dutch twice failed to subdue the Portuguese stronghold on the Island of Mozambique, due to the close cooperation between the locals and the Portuguese.

The Dutch found what they were looking for in Jakarta, conquered by Jan Coen in 1619, later renamed Batavia after the putative Dutch ancestors the Batavians, and which would become the capital of the Dutch East Indies.

For the next forty-four years, the two cities of Goa and Batavia would fight relentlessly, since they stood as the capital of the Portuguese State of India and the Dutch East India Company's base of operations. With the assistance of the Sultanate of Bijapur the Dutch would even attempt to conquer Goa itself, but Portuguese diplomacy defeated this plan.

In fact, Goa had been under intermittent blockade since 1603. Most of the fighting took place in west India, where the Dutch Malabar campaign sought to replace the Portuguese monopoly on the spice trade. Dutch and Portuguese fleets faced off for control of the sea lanes as was the case with the Action of 30 September 1639, while on mainland India the war involved more and more Indian kingdoms and principalities as the Dutch capitalised on local resentment of Portuguese conquests in the early 16th century. In 1624, Fernando de Silva led a Spanish fleet to sack a Dutch ship near the Siamese shoreline. This enraged Songtham, King of Siam, whom held the Dutch in great preference and ordered the attacks and seizures of all the Spaniards.[7]

War between Philip's possessions and other countries led to a deterioration of the Portuguese Empire, as the loss of Hormuz to Persia, aided by England, but the Dutch Empire was the main beneficiary.

In 1640 the Portuguese took advantage of the Catalan Revolt and themselves revolted from the Spanish-dominated Iberian Union. From this point onwards the English decided instead to re-establish their alliance with Portugal.

The VOC gains ground

Despite the Portuguese proclaiming themselves as hostile to the Spanish crown, the VOC nevertheless took the opportunity to prise away the string of coastal fortresses that comprised the Portuguese Empire: Malacca finally succumbed in 1641.

Important battles also took place in the South China Sea, initially with combined fleets of Dutch and English vessels, and subsequently exclusively Dutch ships assaulting Macau. Dutch attempts to capture Macau, to force China to replace the Portuguese or to settle the Pescadores failed, in part because of the long-standing diplomacy between the Portuguese and the Ming, but the Dutch were ultimately successful in acquiring the monopoly of trade with Japan. Meanwhile, the Dutch were unable in four attempts to capture Macau[9] from where Portugal monopolised the lucrative China–Japan trade.

The Dutch established a colony at Tayouan in 1624, present-day Anping in the south of Taiwan, known to the Portuguese as Formosa and in 1642 the Dutch took northern Formosa from the Spanish by force.

The Dutch intervened in the Sinhalese–Portuguese War on Ceylon from 1638 onwards, initially as allies of the Kingdom of Kandy against Portugal. The Dutch conquered Batticaloa in 1639 and Galle in 1640 before the alliance broke down. After a period of triangular warfare between the Dutch, Portuguese, and Kandyans, the alliance was remade in 1649. After exploiting and then double-crossing their Kandyan allies, the Dutch were able to capture Colombo in 1656 and drove the last Portuguese from Ceylon in 1658. Sporadic warfare with Kandy continued for over a century.

In the aftermath of the destruction of the 'Tordesillas system', Portugal had managed to retain Diu but not Hormuz. Goa and Macau had also survived but not Malacca. Nevertheless, the downfall of the Portuguese Indian empire was not territorial but economic: the competition of other European powers whose demographics were more numerous, access to capital easier, and access to markets more direct than Portugal's. Lisbon's distributive monopoly had been stolen from the Islamic world and accrued of more direct competition, it crumbled quickly.

In all, and also because the Dutch were kept busy with their expansion in Indonesia, the conquests made at the expense of the Portuguese were modest: some Indonesian possessions and a few cities and fortresses in Southern India. The most important blow to the Portuguese eastern empire would be the conquest of Malacca in 1641 (depriving them of the control over these straits), Ceylon in 1658, and the Malabar coast in 1663, even after the signing of the peace Treaty of The Hague (1661).

Sugar War – Government-General Vs. the WIC

Surprised by such easy gains in the East, the Republic quickly decided to exploit Portugal's weakness in the Americas. In 1621 the Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compagnie (Authorised West India Company or WIC) was created to take control of the sugar trade and colonise America (the New Netherland project). The Company benefited from a large investment in capital, drawing on the enthusiasm of the best financiers and capitalists of the Republic. The Dutch West India Company would not, however, be as successful as its eastern counterpart.

The Dutch invasion began in 1624 with the conquest of the then capital of the State of Brazil, the city of São Salvador da Bahia, but the Dutch conquest was short lived. In 1625, a joint Spanish–Portuguese fleet of 52 ships and 12,000 men rapidly recaptured Salvador.

In 1630 the Dutch returned, and captured Olinda and then Recife, renamed Mauritsstadt, thus establishing the colony of New Holland. The Portuguese commander Matias de Albuquerque retreated his forces inland, to establish a camp dubbed Arraial do Bom Jesus.[10] Until 1635, the Dutch were unable to harvest sugar due to Portuguese guerrilla attacks, and were virtually confined to the walled perimeter of the cities. Eventually, the Dutch evicted the Portuguese with the assistance of a local landlord named Domingos Fernandes Calabar, but on his retreat to Bahia, Matias de Albuquerque captured Calabar at Porto Calvo, and had him hung for treason.[11]

The Portuguese fought back two Dutch attacks on Bahia in 1638. Nonetheless, by 1641 the Dutch captured São Luís, leaving them in control of northwestern Brazil between Maranhão and Sergipe in the south[12]

Pernambucan Insurrection

The capable John Maurice of Nassau was recalled from the governorship of New Holland in 1644 because of excessive expenditure and under suspicion of corruption. Mutual hostility between the Catholic Portuguese and Protestant Dutch, and harsh measures to collect from indebted land-owners who had their estates ravaged in the war, ensured that Portuguese settlers came to resent the authority of the new Dutch administration.

In 1645, most of Dutch Brazil revolted under the leadership of mulatto land-owner João Fernandes Vieira, who proclaimed himself loyal to the Portuguese Crown. WIC forces were defeated at the Battle of Tabocas, virtually confining the Dutch to the fortified urban perimeters of coastal cities, defended by contingents of German and Flemish mercenaries. Still in that year, the Dutch abandoned São Luís. The Second Battle of Guararapes, in 1649, marked the beginning of the end of Dutch occupation of Portuguese Brazil, until their final expulsion from Recife in 1654.

West Africa and Angola

At the same time, the Dutch organized incursions against the Portuguese possessions in Africa in order to take control of the slave trade and complete the trade triangle that would ensure the economic prosperity of New Holland.

In 1626, a Dutch expedition to take Elmina was almost wiped out in an ambush by the Portuguese, but in 1637, Elmina fell to the Dutch. In 1641 (after a truce between Portugal and the Netherlands had been signed), the Dutch captured the island of São Tomé and before the end of 1642, the rest of Portuguese Gold Coast followed.

.jpg.webp)

In August 1641 the Dutch formed a three-way alliance with the Kingdom of Kongo and Queen Nzinga of Ndongo, and with their assistance captured Luanda and Benguela, though without preventing the Portuguese from retreating inland into strongholds like Massangano, Ambaca, and Muxima. With a steady source of slaves now secure, the Dutch abstained from further action, presuming that their allies would suffice against the Portuguese. Nonetheless, lacking artillery and firearms, Queen Nzinga and the Kongo proved unable to decisively defeat the Portuguese and their cannibalistic Imbangala allies.

The recapture of Luanda and São Tomé

As the Portuguese were unable to send sufficient reinforcements to their colonies due to the ongoing Restoration War in mainland Portugal, in 1648 the Portuguese governor of the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, Salvador Correia de Sá, organized a military expedition to retake Luanda from the Dutch, directly from Brazil.

In early August, the fleet reached Luanda, where de Sá communicated to the Dutch garrison that since the Dutch would not respect the terms of the truce, the Portuguese felt no obligation to do so either. Although the Portuguese were outnumbered, a swift display of force achieved on August 15 the surrender of Luanda and all Dutch forces in Angola. Upon hearing of the fall of Luanda, Queen Nzinga retreated to Matamba, while the Dutch in São Tomé abandoned the island, which was reoccupied by the Portuguese later that year.

Second Treaty of The Hague (1661) and peace (1663)

The Dutch, determined to recover or retain their territories, postponed the end of the conflict. But as they had to contend with the English at the same time they eventually decided to offer terms.

See also

|

|

|

Notes

- Smith, Roger (1986). "Early Modern Ship-types, 1450–1650". The Newberry Library. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ‘The Presence of the "Portugals" in Macau and Japan in Richard Hakluyt's Navigations Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine’, Rogério Miguel Puga, Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies, vol. 5, December 2002, pp. 81–116.

- Van Linschoten, Jan Huyghen. Voyage to Goa and Back, 1583–1592, with His Account of the East Indies : From Linschoten's Discourse of Voyages, in 1598/Jan Huyghen Van Linschoten. Reprint. New Delhi, AES, 2004, xxiv, 126 p., $11. ISBN 81-206-1928-5.

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011) Portuguese Sea Battles Volume V

- Boxer (1969), p. 23.

- Boxer (1965), p. 189.

- Tricky Vandenberg. "History of Ayutthaya - Foreign Settlements - Portuguese Settlement". Ayutthaya-history.com. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Boxer (1969), p. 24.

- Shipp, p. 22.

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011) Portuguese Sea Battles Volume VI – 1627–1668 p. 57.

- Saturnino Monteiro (2011) Portuguese Sea Battles Volume VI – 1627–1668 p. 127.

- Klein p. 47.

- Levine, Robert M.; Crocitti, John J.; Kirk, Robin; Starn, Orin (1999). The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics. p. 121. ISBN 0822322900. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- "Recife—A City Made by Sugar". Awake!. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

References

| Library resources about Dutch–Portuguese War |

- Boxer, C. R. (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. New York: A.A. Knopf. OCLC 56691.

External links

- Dutch and Portuguese colonial legacy throughout Africa and Asia

- Wars Directory

- Naval Battles of Portugal (Portuguese)

- Portuguese Armada's history of naval battles (Portuguese)

.jpg.webp)