Portuguese Malacca

Portuguese control of Malacca, a city on the Malay Peninsula, lasted for 130 years (1511–1641). It was conquered from the Malacca Sultanate as part of Portuguese attempts to gain control of trade in the region. Although multiple attempts to conquer it were repulsed, the city was eventually lost to an alliance of Dutch and regional forces, thus entering a period of Dutch rule.

Portuguese Fort of Malacca | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1511–1641 | |||||||||

Malacca, shown within modern Malaysia | |||||||||

_(14743853356).jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca by Ferdinand Magellan, ca. 1509-1512 | |||||||||

| Status | Portuguese colony | ||||||||

| Capital | Malacca Town | ||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese, Malay | ||||||||

| King of Portugal | |||||||||

• 1511–1521 | Manuel I | ||||||||

• 1640–1641 | John IV | ||||||||

| Captains-major | |||||||||

• 1512–1514 (first) | Rui de Brito Patalim | ||||||||

• 1638–1641 (last) | Manuel de Sousa Coutinho | ||||||||

| Captains-general | |||||||||

• 1616–1635 (first) | António Pinto da Fonseca | ||||||||

• 1637–1641 (last) | Luís Martins de Sousa Chichorro | ||||||||

| Historical era | Imperialism | ||||||||

• Fall of Malacca Sultanate | 15 August 1511 | ||||||||

• Dutch invasion | 14 January 1641 | ||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malaysia |

|

|

|

History

According to the 16th-century Portuguese historian Emanuel Godinho de Erédia, the site of the old city of Malacca was named after the malacca tree (Phyllanthus emblica), fruit-bearing trees along the banks of a river called Airlele (Ayer Leleh). The Airlele river was said to originate from Buquet China (present-day Bukit Cina). Eredia cited that the city was founded by Permicuri (i.e. Parameswara) the first King of Malacca in 1411.

The capture of Malacca

The news of Malacca's wealth attracted the attention of Manuel I, King of Portugal and he sent Admiral Diogo Lopes de Sequeira to find Malacca, to make a trade compact with its ruler as Portugal's representative east of India. The first European to reach Malacca and Southeast Asia, Sequeira arrived in Malacca in 1509. Although he was initially well received by Sultan Mahmud Shah, trouble however quickly ensued.[1] The general feeling of rivalry between Islam and Christianity was invoked by a group of Goa Muslims in the sultan's court after the Portuguese had captured Goa.[2] The international Muslim trading community convinced Mahmud that the Portuguese were a grave threat. Mahmud subsequently captured several of his men, killed others and attempted to attack the four Portuguese ships, although they escaped. As the Portuguese had found in India, conquest would be the only way they could establish themselves in Malacca.[1]

In April 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque set sail from Goa to Malacca with a force of some 1200 men and seventeen or eighteen ships.[1] The Viceroy made a number of demands—one of which was for permission to build a fortress as a Portuguese trading post near the city.[2] The Sultan refused all the demands. Conflict was unavoidable, and after 40 days of fighting, Malacca fell to the Portuguese on 24 August. A bitter dispute between Sultan Mahmud and his son Sultan Ahmad also weighed down the Malaccan side.[1]

Following the defeat of the Malacca Sultanate on 15 August 1511 in the capture of Malacca, Afonso de Albuquerque sought to erect a permanent form of fortification in anticipation of the counterattacks by Sultan Mahmud. A fortress was designed and constructed encompassing a hill, lining the edge of the sea shore, on the south east of the river mouth, on the former site of the Sultan's palace. Albuquerque remained in Malacca until November 1511 preparing its defences against any Malay counterattack.[1] Sultan Mahmud Shah was forced to flee Malacca.

A Portuguese port in a hostile region

.jpg.webp)

As the first base of European Christian trading kingdom in Southeast Asia, it was surrounded by numerous emerging native Muslim states. Also, with hostile initial contact with the local Malay policy, Portuguese Malacca faced severe hostility. They endured years of battles started by Malay sultans who wanted to get rid of the Portuguese and reclaim their land. The Sultan made several attempts to retake the capital. He rallied the support from his ally the Sultanate of Demak in Java who, in 1511, agreed to send naval forces to assist. Led by Pati Unus, the Sultan of Demak, the combined Malay–Java efforts failed and were fruitless. The Portuguese retaliated and forced the sultan to flee to Pahang. Later, the sultan sailed to Bintan Island and established a new capital there. With a base established, the sultan rallied the disarrayed Malay forces and organized several attacks and blockades against the Portuguese's position. Frequent raids on Malacca caused the Portuguese severe hardship. In 1521 the second Demak campaign to assist the Malay Sultan to retake Malacca was launched, however once again failed with the cost of the Demak Sultan's life. He was later remembered as Pangeran Sabrang Lor or the Prince who crossed (the Java Sea) to North (Malay Peninsula). The raids helped convince the Portuguese that the exiled sultan's forces must be silenced. A number of attempts were made to suppress the Malay forces, but it wasn't until 1526 that the Portuguese finally razed Bintan to the ground. The sultan then retreated to Kampar in Riau, Sumatra where he died two years later. He left behind two sons named Muzaffar Shah and Alauddin Riayat Shah II.

Muzaffar Shah was invited by the people in the north of the peninsula to become their ruler, establishing the Sultanate of Perak. Meanwhile, Mahmud's other son, Alauddin succeeded his father and made a new capital in the south. His realm was the Johor Sultanate, the successor of Malacca.

Several attempts to remove Malacca from Portuguese rule were made by the Sultan of Johor. A request sent to Java in 1550 resulted in Queen Kalinyamat, the regent of Jepara, sending 4,000 soldiers aboard 40 ships to meet the Johor sultan's request to take Malacca. The Jepara troops later joined forces with the Malay alliance and managed to assemble around 200 warships for the upcoming assault. The combined forces attacked from the north and captured most of Malacca, but the Portuguese managed to retaliate and force back the invading forces. The Malay alliance troops were thrown back to the sea, while the Jepara troops remained on shore. Only after their leaders were slain did the Jepara troops withdraw. The battle continued on the beach and in the sea resulting in more than 2,000 Jepara soldiers being killed. A storm stranded two Jepara ships on the shore of Malacca, and they fell prey to the Portuguese. Fewer than half of the Jepara soldiers managed to leave Malacca.

In 1567, Prince Husain Ali I Riayat Syah from the Sultanate of Aceh launched a naval attack to oust the Portuguese from Malacca, but this once again ended in failure. In 1574 a combined attack from Aceh Sultanate and Javanese Jepara tried again to capture Malacca from the Portuguese, but ended in failure due to poor coordination.

Competition from other ports such as Johor saw Asian traders bypass Malacca and the city began to decline as a trading port.[3] Rather than achieving their ambition of dominating it, the Portuguese had fundamentally disrupted the organisation of the Asian trade network. Rather than a centralised port of exchange of Asian wealth exchange, or a Malay state to police the Strait of Malacca that made it safe for commercial traffic, trade was now scattered over a number of ports amongst bitter warfare in the Straits.[3]

Chinese military retaliation against Portugal

_(14578526689).jpg.webp)

The Malay Malacca Sultanate was a tributary state and ally to Ming Dynasty China. When Portugal conquered Malacca in 1511, the Chinese responded with violent force against the Portuguese.

Following the attack, the Chinese refused to accept a Portuguese embassy.[4]

The Chinese Imperial Government imprisoned and executed multiple Portuguese diplomatic envoys after torturing them in Guangzhou. A Malaccan envoy had informed the Chinese of the Portuguese seizure of Malacca, which the Chinese responded to with hostility toward the Portuguese. The Malaccan envoy told the Chinese of the deception the Portuguese used, disguising plans for conquering territory as mere trading activities, and told his tale of deprivations at the hands of the Portuguese.[5] Malacca was under Chinese protection and the Portuguese invasion angered the Chinese.[6]

Due to the Malaccan Sultan lodging a complaint against the Portuguese invasion to the Chinese Emperor, the Portuguese were greeted with hostility from the Chinese when they arrived in China.[7] The Sultan's complaint caused "a great deal of trouble" to Portuguese in China.[8] The Chinese were very "unwelcoming" to the Portuguese.[9] The Malaccan Sultan, based in Bintan after fleeing Malacca, sent a message to the Chinese, which combined with Portuguese banditry and violent activity in China, led the Chinese authorities to execute 23 Portuguese and torture the rest of them in jails. After the Portuguese set up posts for trading in China and committed piratical activities and raids in China, the Chinese responded with the complete extermination of the Portuguese in Ningbo and Quanzhou[10] Pires, a Portuguese trade envoy, was among those who died in the Chinese dungeons.[11]

However, with gradual improvement of relations and aid given against the Wokou pirates along China's shores, by 1557 Ming China finally agreed to allow the Portuguese to settle at Macau in a new Portuguese trade colony.[12] The Malay Sultanate of Johor also improved relations with the Portuguese and fought alongside them against the Aceh Sultanate.

Chinese boycott and counterattacks

Chinese traders boycotted Malacca after it fell under Portuguese control, some Chinese in Java assisted in Muslim attempts to reconquer the city from Portugal using ships. The Java Chinese participation in retaking Malacca was recorded in "The Malay Annals of Semarang and Cerbon".[13] The Chinese traders did business with the Malays and Javanese instead of the Portuguese.[14]

Dutch conquest and the end of Portuguese Malacca

By the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) began contesting Portuguese power in the East. At that time, the Portuguese had transformed Malacca into an impregnable fortress, the Fortaleza de Malaca, controlling access to the sea lanes of the Straits of Malacca and the spice trade there. The Dutch started by launching small incursions and skirmishes against the Portuguese. The first serious attempt was the siege of Malacca in 1606 by the third VOC fleet from Holland with eleven ships, commanded by Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge that led to the naval battle of Cape Rachado. Although the Dutch were routed, the Portuguese fleet of Martim Afonso de Castro, the Viceroy of Goa, suffered heavier casualties and the battle rallied the forces of the Sultanate of Johor into an alliance with the Dutch and later on with the Aceh Sultanate.

Around that same time period, the Sultanate of Aceh had grown into a regional power with a formidable naval force and regarded Portuguese Malacca as potential threat. In 1629, Iskandar Muda of the Aceh Sultanate sent several hundred ships to attack Malacca, but the mission was a devastating failure. According to Portuguese sources, all of his ships were destroyed and lost some 19,000 men in the process.

The Dutch with their local allies assaulted and finally wrested Malacca from the Portuguese in January 1641. This combined Dutch-Johor-Aceh efforts effectively destroyed the last bastion of Portuguese power, reducing their influence in the archipelago. The Dutch settled in the city as Dutch Malacca, however the Dutch had no intention to make Malacca their main base, and concentrated on building Batavia (today Jakarta) as their headquarters in the orient instead. The Portuguese ports in the spice-producing areas of Mollucas also fell to the Dutch in the following years. With these conquests, the last Portuguese colonies in Asia remained confined to Portuguese Timor, Goa, Daman and Diu in Portuguese India and Macau until the 20th century.

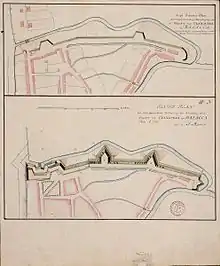

Fortaleza de Malaca

The early core of the fortress system was a quadrilateral tower called Fortaleza de Malaca. Measurement was given as 10 fathoms per side with a height of 40 fathoms. It was constructed at the foot of the fortress hill, next to the sea. To its east was constructed a circular wall of mortar and stone with a well in the middle of the enclosure.

Over the years, constructions began to fully fortify the fortress hill. The pentagonal system began at the farthest point of the cape near south east of the river mouth, towards the west of the Fortaleza. At this point two ramparts were built at right angles to each other lining the shores. The one running northward toward the river mouth was 130 fathoms in length to the bastion of São Pedro while the other one ran for 75 fathoms to the east, curving inshore, ending at the gate and bastion of Santiago.

From the bastion of São Pedro the rampart turned north east 150 fathoms past the Custom House Terrace gateway ending at the northernmost point of the fortress, the bastion of São Domingos. From the gateway of São Domingos, an earth rampart ran south-easterly for 100 fathoms ending at the bastion of the Madre de Deus. From here, beginning at the gate of Santo António, past the bastion of the Virgins, the rampart ended at the gateway of Santiago.

Overall the city enclosure was 655 fathoms and 10 palms (short) of a fathom.

Gateways

Four gateways were built for the city;

- Porta de Santiago

- The gateway of the Custom House Terrace

- Porta de São Domingos

- Porta de Santo António

Of these four gateways only two were in common use and open to traffic: the Gate of Santo António linking to the suburb of Yler and the western gate at the Custom House Terrace, giving access to Tranqueira and its bazaar.

Destruction

After almost 300 years of existence, in 1806, the British, unwilling to maintain the fortress and wary of letting other European powers take control of it, ordered its slow destruction. The fort was almost totally demolished but for the timely intervention of Sir Stamford Raffles visiting Malacca in 1810. The only remnants of the earliest Portuguese fortress in Southeast Asia is the Porta de Santiago, now known as the A Famosa.

Malacca Town during the Portuguese Era

Outside of the fortified town centre lie the three suburbs of Malacca. The suburb of Upe (Upih), generally known as Tranqueira (modern day Tengkera) from the rampart of the fortress. The other two suburb were Yler (Hilir) or Tanjonpacer (Tanjung Pasir) and the suburb of Sabba.

Tranqueira

Tranqueira was the most important suburb of Malacca. The suburb was rectangular in shape, with a northern walled boundary, the straits of Malacca to the south and the river of Malacca (Rio de Malaca) and the fortaleza's wall to the east. It was the main residential quarters of the city. However, in war, the residents of the quarters would be evacuated to the fortress. Tranqueira was divided into a further two parishes, São Tomé and São Estêvão. The parish of S.Tomé was called Campon Chelim (Malay: Kampung Keling). It was described that this area was populated by the Chelis of Choromandel. The other suburb of São Estêvão was also called Campon China (Kampung Cina).

Erédia described the houses as made of timber but roofed by tiles. A stone bridge with sentry crosses the river Malacca to provide access to the Malacca Fortress via the eastern Custome House Terrace. The centre of trade of the city was also located in Tranqueira near the beach on the mouth of the river called the Bazaar of the Jaos (Jowo/Jawa i.e. Javanese).

In the present day, this part of the city is called Tengkera.

Yler

The district of Yler (Hilir) roughly covered Buquet China (Bukit Cina) and the south-eastern coastal area. The Well of Buquet China was one of the most important water sources for the community. Notable landmarks included the Church of the Madre De Deus and the Convent of the Capuchins of São Francisco. Other notable landmarks included Buquetpiatto (Bukit Piatu). The boundaries of this unwalled suburb were said to extend as far as Buquetpipi and Tanjonpacer.

Tanjonpacer (Malay: Tanjung Pasir) was later renamed Ujong Pasir. A community descended from Portuguese settlers is still located here in present-day Malacca. However, this suburb of Yler is now known as Banda Hilir. Modern land reclamations (for the purpose of building the commercial district of Melaka Raya) have, however, denied Banda Hilir the access to the sea that it formerly had.

Sabba

The houses of this suburb were built along the edges of the river. Some of the original Muslim Malay inhabitants of Malacca lived in the swamps of Nypeiras tree, where they were known to make Nypa (Nipah) wine by distillation for trade. This suburb was considered the most rural, being a transition to the Malacca hinterland, where timber and charcoal traffic passed through into the city. Several Christian parishes also lay outside the city along the river; São Lázaro, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Hope. While Muslim Malays inhabited the farmlands deeper into the hinterland.

In later periods of Dutch, British and modern day Malacca, the name of Sabba was made obsolete. However, its area encompassed parts of what is now Banda Kaba, Bunga Raya and Kampung Jawa; and the modern city centre of Malacca

Portuguese immigration

The Portuguese also shipped over many Orfãs d'El-Rei to Portuguese colonies overseas in Africa and India, and also to Portuguese Malacca. Orfãs d'El-Rei literally translates to "Orphans of the King", and they were Portuguese girl orphans sent to overseas colonies to marry Portuguese settlers.

Portuguese administration of Malacca

Malacca was administered by a Governor (a Captain-Major), who was appointed for a term of three-years, as well as a Bishop and church dignitaries representing the Episcopal See, municipal officers, Royal Officials for finance and justice and a local native Bendahara to administer the native Muslims and foreigners under the Portuguese jurisdiction.

| Captains-major | From | Until |

|---|---|---|

| Rui de Brito Patalim | 1512 | 1514 |

| Jorge de Albuquerque (1st time) | 1514 | 1516 |

| Jorge de Brito | 1516 | 1517 |

| Nuno Vaz Pereira | 1517 | 1518 |

| Afonso Lopes da Costa | 1518 | 1519 |

| Garcia de Sá (1st time) | 1519 | 1521 |

| Jorge de Albuquerque (2nd time) | 1521 | 1525 |

| Pero de Mascarenhas | 1525 | 1526 |

| Jorge Cabral | 1526 | 1528 |

| Pero de Faria | 1528 | 1529 |

References

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 23. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Mohd Fawzi bin Mohd Basri; Mohd Fo'ad bin Sakdan; Azami bin Man (2002). Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah Sejarah Tingkatan 1. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. p. 95. ISBN 983-62-7410-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: Macmillan. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-521-82274-2. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

The Portuguese spent several years trying to establish formal relations with China, but Melaka had been part of the Chinese tributary system, and the Chinese had found out about the Portuguese attack, making them suspicious. The embassy was formally rejected in 1521.

- Nigel Cameron (1976). Barbarians and mandarins: thirteen centuries of Western travelers in China. Volume 681 of A phoenix book (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 143. ISBN 0-226-09229-1. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

envoy, had most effectively poured out his tale of woe, of deprivation at the hands of the Portuguese in Malacca; and he had backed up the tale with others concerning the reprehensible Portuguese methods in the Moluccas, making the case (quite truthfully) that European trading visits were no more than the prelude to annexation of territory. With the tiny sea power at this time available to the Chinese

- Zhidong Hao (2011). Macau History and Society (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Pires came as an ambassador to Beijing to negotiate trade terms and settlements with China. He did make it to Beijing, but the mission failed because first, while Pires was in Beijing, the dethroned Sultan of Malacca also sent an envoy to Beijing to complain to the emperor about the Portuguese attack and conquest of Malacca. Malacca was part of China's suzerainty when the Portuguese took it. The Chinese were apparently not happy with what the Portuguese did there.

- Ahmad Ibrahim; Sharon Siddique; Yasmin Hussain, eds. (1985). Readings on Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 11. ISBN 9971-988-08-9. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

in China was far from friendly; this, it seems, had something to do with the complaint which the ruler of Malacca, conquered by the Portuguese in 1511, had lodged with the Chinese emperor, his suzerain.

- John Horace Parry (1 June 1981). The discovery of the sea. University of California Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-520-04237-9. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

In 1511 ... Alboquerque himself sailed ... to attack Malacca ... The Sultan of Malacca fled down the coast, to establish himself in the marshes of Johore, whence he sent petitions for redress to his remote suzerain, the Chinese Emperor. These petitions later caused the Portuguese, in their efforts to gain admission to trade at Canton, a great deal of trouble

- John Horace Parry (1 June 1981). The discovery of the sea. University of California Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-520-04237-9. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

When the Portuguese tried to penetrate, in their own ships, to Canton itself, their reception by the Chinese authorities—understandably, in view of their reputation at Malacca—was unwelcoming, and several decades elapsed before they secured a tolerated toehold at Macao.

- Ernest S. Dodge (1976). Islands and Empires: Western Impact on the Pacific and East Asia. Volume 7 of Europe and the World in Age of Expansion. U of Minnesota Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-8166-0853-9. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

The inexusable behavior of the Portuguese, combined with the ill-chosen language of the letters which Pires presented to the celestial emperor, supplemented by a warning from the Malay sultan of Bintan, persuaded the Chinese that Pires was indeed up to no good

- Kenneth Scott Latourette (1964). The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1–2 (4, reprint ed.). Macmillan. p. 235. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

The Moslem ruler of Malacca, whom they had dispossessed, complained of them to the Chinese authorities. A Portuguese envoy, Pires, who reached Peking in 1520 was treated as a spy, was conveyed by imperial order to Canton

- Wills, John E., Jr. (1998). "Relations with Maritime Europe, 1514–1662," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2, 333–375. Edited by Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank, and Albert Feuerwerker. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24333-5, 343-344.

- C. Guillot; Denys Lombard; Roderich Ptak, eds. (1998). From the Mediterranean to the China Sea: miscellaneous notes. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 179. ISBN 3-447-04098-X. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Chinese authors have argued, the Malacca-Chinese were not treated too favorably by the Portuguese ... it is generally true that Chinese ships tended to avoid Malacca after 1511, sailing to other ports instead. Presumably these ports were mainly on the east coast of the Malayan peninsula and on Sumatra. Johore, in the deep south of the peninsula, was another place where many Chinese went ... After 1511, many Chinese who were Muslims sided with other Islamic traders against the Portuguese; according to The Malay Annals of Semarang and Cerbon, Chinese settlers living on northern Java even became involved in counter-attacks on Malacca. Javanese vessels were indeed sent out but suffered a disastrous defeat. Demak and Japara alone lost more than seventy sail.

- Peter Borschberg, National University of Singapore. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Fundação Oriente (2004). Peter Borschberg (ed.). Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka area and adjacent regions (16th to 18th century). Volume 14 of South China and maritime Asia (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 12. ISBN 3-447-05107-8. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

still others withdrew to continue business with the Javanese, Malays and Gujaratis...When the Islamic world considered counter-attacks against Portuguese Melaka, some Chinese residents may have provided ships and capital. These Chinese had their roots either in Fujian, or else may have been of Muslim descent. This group may have consisted of small factions that fled Champa after the crisis of 1471.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)