Climate change in Australia

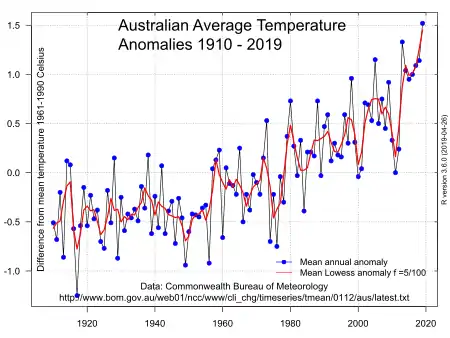

Climate change in Australia has been a critical issue since the beginning of the 21st century. Australia is becoming hotter, and more prone to extreme heat, bushfires, droughts, floods and longer fire seasons because of climate change. Since the beginning of the 20th century Australia has experienced an increase of nearly 1 °C in average annual temperatures, with warming occurring at twice the rate over the past 50 years than in the previous 50 years.[1] Recent climate events such as extremely high temperatures and widespread drought have focused government and public attention on the impacts of climate change in Australia.[2] Rainfall in southwestern Australia has decreased by 10–20% since the 1970s, while southeastern Australia has also experienced a moderate decline since the 1990s. Rainfall is expected to become heavier and more infrequent, as well as more common in summer rather than in winter. Water sources in the southeastern areas of Australia have depleted due to increasing population in urban areas coupled with persistent prolonged drought.

Predictions measuring the effects of global warming on Australia assert that global warming will negatively impact the continent's environment, economy, and communities. Australia is vulnerable to the effects of global warming projected for the next 50 to 100 years because of its extensive arid and semi-arid areas, an already warm climate, high annual rainfall variability, and existing pressures on water supply. The continent's high fire risk increases this susceptibility to change in temperature and climate. Additionally, Australia's population is highly concentrated in coastal areas, and its important tourism industry depends on the health of the Great Barrier Reef and other fragile ecosystems. The impacts of climate change in Australia will be complex and to some degree uncertain, but increased foresight may enable the country to safeguard its future through planned mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation may reduce the ultimate extent of climate change and its impacts, but requires global solutions and cooperation, while adaptation can be performed at national and local levels.[3]

The exposure of Indigenous Australians to climate change impacts is exacerbated by existing socio-economic disadvantages which are linked to colonial and post-colonial marginalisation.[4] Climate issues include wild fires, heatwaves, floods, cyclones, rising sea-levels, rising temperatures, and erosion.[5][6][7] The communities most affected by climate changes are those in the North where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 30% of the population.[8] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities located in the coastal north are the most disadvantaged due to social and economic issues and their reliance on traditional land for food, culture, and health. This has begged the question for many community members in these regions, should they move away from this area or remain present.[8]

Greenhouse gas emissions

Pre-instrumental climate change

Paleoclimatic records indicate that during glacial maxima Australia was extremely arid,[12] with plant pollen fossils showing deserts as far as northern Tasmania and a vast area of less than 12% vegetation cover over all of South Australia and adjacent regions of other states. Forest cover was largely limited to sheltered areas of the east coast and the extreme southwest of Western Australia.

During these glacial maxima the climate was also much colder and windier than today.[13] Minimum temperatures in winter in the centre of the continent were as much as 9 °C (16.9F°) lower than they are today. Hydrological evidence for dryness during glacial maxima can also be seen at major lakes in Victoria's Western District, which dried up between around 20,000 and 15,000 years ago and re-filled from around 12,000 years ago.[14]

During the early Holocene, there is evidence from Lake Frome in South Australia and Lake Woods near Tennant Creek that the climate between 8,000 and 9,500 years ago and again from 7,000 to 4,200 years ago was considerably wetter than over the period of instrumental recording since about 1885.[15] The research that gave these records also suggested that the rainfall flooding Frome was certainly summer-dominant rainfall because of pollen counts from grass species. Other sources[16] suggest that the Southern Oscillation may have been weaker during the early Holocene and rainfall over northern Australia less variable as well as higher. The onset of modern conditions with periodic wet season failure is dated at around 4,000 years before the present.

In southern Victoria, there is evidence for generally wet conditions except for a much drier spell between about 3,000 and 2,100 years before the present,[17] when it is believed Lake Corangamite fell to levels well below those observed between European settlement and the 1990s. After this dry period, Western District lakes returned to their previous levels fairly quickly and by 1800 they were at their highest levels in the forty thousand years of record available.

Elsewhere, data for most of the Holocene are deficient, largely because methods used elsewhere to determine past climates (like tree-ring data) cannot be used in Australia owing to the character of its soils and climate. Recently, however, coral cores have been used to examine rainfall over those areas of Queensland draining into the Great Barrier Reef.[18] The results do not provide conclusive evidence of man-made climate change, but do suggest the following:

- There has been a marked increase in the frequency of very wet years in Queensland since the end of the Little Ice Age, a theory supported by there being no evidence for any large Lake Eyre filling during the LIA.

- The dry era of the 1920s and 1930s may well have been the driest period in Australia over the past four centuries.

A similar study, not yet published, is planned for coral reefs in Western Australia.

Records exist of floods in a number of rivers, such as the Hawkesbury, from the time of first settlement. These suggest that, for the period beginning with the first European settlement, the first thirty-five years or so were wet and were followed by a much drier period up to the mid-1860s,[19] when usable instrumental records started.

Instrumental climate records

Development of an instrumental network

Although rain gauges were installed privately by some of the earliest settlers, the first instrumental climate records in Australia were not compiled until 1840 at Port Macquarie. Rain gauges were gradually installed at other major centres across the continent, with the present gauges in Melbourne and Sydney dating from 1858 and 1859, respectively.

In eastern Australia, where the continent's first large-scale agriculture began, a large number of rain gauges were installed during the 1860s and by 1875 a comprehensive network had been developed in the "settled" areas of that state.[20] With the spread of the pastoral industry to the north of the continent during this period, rain gauges were established extensively in newly settled areas, reaching Darwin by 1869, Alice Springs by 1874, and the Kimberley, Channel Country and Gulf Savannah by 1880.

By 1885,[21] most of Australia had a network of rainfall reporting stations adequate to give a good picture of climatic variability over the continent. The exceptions were remote areas of western Tasmania, the extreme southwest of Western Australia, Cape York Peninsula,[22] the northern Kimberley and the deserts of northwestern South Australia and southeastern Western Australia. In these areas good-quality climatic data were not available for quite some time after that.

Temperature measurements, although made at major population centres from days of the earliest rain gauges, were generally not established when rain gauges spread to more remote locations during the 1870s and 1880s. Although they gradually caught up in number with rain gauges, many places which have had rainfall data for over 125 years have only a few decades of temperature records.

Climate history based on instrumental records

Australia's instrumental record from 1885 to the present shows the following broad picture:

Conditions from 1885 to 1898 were generally fairly wet, though less so than in the period since 1968. The only noticeably dry years in this era were 1888 and 1897. Although some coral core data[23] suggest that 1887 and 1890 were, with 1974, the wettest years across the continent since settlement, rainfall data for Alice Springs, then the only major station covering the interior of the Northern Territory and Western Australia, strongly suggest that 1887 and 1890 were overall not as wet as 1974 or even 2000.[24] In New South Wales and Queensland, however, the years 1886–1887 and 1889–1894 were indeed exceptionally wet. The heavy rainfall over this period has been linked with a major expansion of the sheep population[25] and February 1893 saw the disastrous 1893 Brisbane flood.

A drying of the climate took place from 1899 to 1921, though with some interruptions from wet El Niño years, especially between 1915 and early 1918 and in 1920–1921, when the wheat belt of the southern interior was drenched by its heaviest winter rains on record. Two major El Niño events in 1902 and 1905 produced the two driest years across the whole continent, whilst 1919 was similarly dry in the eastern States apart from the Gippsland.

The period from 1922 to 1938 was exceptionally dry, with only 1930 having Australia-wide rainfall above the long-term mean and the Australia-wide average rainfall for these seventeen years being 15 to 20 per cent below that for other periods since 1885. This dry period is attributed in some sources to a weakening of the Southern Oscillation[26] and in others to reduced sea surface temperatures.[27] Temperatures in these three periods were generally cooler than they are currently, with 1925 having the coolest minima of any year since 1910. However, the dry years of the 1920s and 1930s were also often quite warm, with 1928 and 1938 having particularly high maxima.

The period from 1939 to 1967 began with an increase in rainfall: 1939, 1941 and 1942 were the first close-together group of relatively wet years since 1921. From 1943 to 1946, generally dry conditions returned, and the two decades from 1947 saw fluctuating rainfall. 1950, 1955 and 1956 were exceptionally wet except 1950 and 1956 over arid and wheatbelt regions of Western Australia. 1950 saw extraordinary rains in central New South Wales and most of Queensland: Dubbo's 1950 rainfall of 1,329 mm (52.3 in) can be estimated to have a return period of between 350 and 400 years, whilst Lake Eyre filled for the first time in thirty years. In contrast, 1951, 1961 and 1965 were very dry, with complete monsoon failure in 1951/1952 and extreme drought in the interior during 1961 and 1965. Temperatures over this period initially fell to their lowest levels of the 20th century, with 1949 and 1956 being particularly cool, but then began a rising trend that has continued with few interruptions to the present.

Since 1968, Australia's rainfall has been 15 per cent higher than between 1885 and 1967. The wettest periods have been from 1973 to 1975 and 1998 to 2001, which comprise seven of the thirteen wettest years over the continent since 1885. Overnight minimum temperatures, especially in winter, have been markedly higher than before the 1960s, with 1973, 1980, 1988, 1991, 1998 and 2005 outstanding in this respect. There has been a marked decrease in the frequency of frost across Australia.[28]

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, Australia's annual mean temperature for 2009 was 0.9 °C above the 1961–90 average, making it the nation's second-warmest year since high-quality records began in 1910.[29]

According to the Bureau of Meteorology's 2011 Australian Climate Statement, Australia had lower than average temperatures in 2011 as a consequence of a La Niña weather pattern; however, "the country's 10-year average continues to demonstrate the rising trend in temperatures, with 2002–2011 likely to rank in the top two warmest 10-year periods on record for Australia, at 0.52 °C (0.94 °F) above the long-term average".[30] Furthermore, 2014 was Australia's third warmest year since national temperature observations commenced in 1910.[31][32]

Current effects of climate change on Australia

According to the CSIRO and Garnaut Climate Change Review, climate change is expected to have numerous adverse effects on many species, regions, activities and much infrastructure and areas of the economy and public health in Australia. The Stern Report and Garnaut Review on balance expect these to outweigh the costs of mitigation.[33]

Sustained climate change could have drastic effects on the ecosystems of Australia. For example, rising ocean temperatures and continual erosion of the coasts from higher water levels will cause further bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. Beyond that, Australia's climate will become even harsher, with more powerful tropical cyclones and longer droughts.[34]

The impacts of climate change will vary significantly across Australia. The Australian Government appointed Climate Commission have prepared summary reports on the likely impacts of climate change for regions across Australia, including: Queensland, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.[35]

According to the Climate Commission (now the Climate Council) report in 2013, the extreme heatwaves, flooding and bushfires striking Australia have been intensified by climate change and will get worse in future in terms of their impacts on people, property, communities and the environment.[36] The summer of 2012/2013 included the hottest summer, hottest month and hottest day on record. The cost of the 2009 bushfires in Victoria was estimated at A$4.4bn (£3bn) and the Queensland floods of 2010/2011 cost over A$5bn.[37][38][39]

By 2014, another report revealed that, due to the change in climatic patterns, the heat waves were found to be increasingly more frequent and severe, with an earlier start to the season and longer duration.[36] The report also cited that the current heat wave levels in Australia were not anticipated to occur until 2030. All these underscored the kind of threat that Australia faces. As a developed country, its coping strategies are more sophisticated but it is the rate of change that will pose the bigger risks.[40]

Sea level rise

.jpg.webp)

The Australian Government released a report saying that up to 247,600 houses are at risk from flooding from a sea level rise of 1.1 metres. There were 39,000 buildings located within 110 metres of 'soft' erodible shorelines, at risk from a faster erosion due to sea level rise.[41] Adaptive responses to this specific climate change threat are often incorporated in the coastal planning policies and recommendations at the state level.[42] For instance, the Western Australia State Coastal Planning Policy established a sea level rise benchmark for initiatives that address the problem over a 100-year period.[42]

Economy

In 2008 the Treasurer and the Minister for Climate Change and Water released a report that concluded the economy will grow with an emissions trading scheme in place.[43]

A report released in October 2009 by the Standing Committee on Climate Change, Water, Environment and the Arts, studying the effects of a 1-metre sea level rise, quite possible within the next 30–60 years, concluded that around 700,000 properties around Australia, including 80,000 buildings, would be inundated, the collective value of these properties is estimated at $155 billion.[44]

In 2019 the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences published a report about the impact of climate change on the profitability of the Australian agriculture, saying that the profit of the Australian farms was cut by 22% due to climate change in the years 2000–2019.[45]

Water (droughts and floods)

Bureau of Meteorology records since the 1860s show that a 'severe' drought has occurred in Australia, on average, once every 18 years.[46]

Rainfall in southwestern Australia has decreased by 10–20% since the 1970s, while southeastern Australia has also experienced a moderate decline since the 1990s.[47] Rainfall is expected to become heavier and more infrequent, as well as more common in summer rather than in winter.[48]

In June 2008 it became known that an expert panel had warned of long-term, maybe irreversible, severe ecological damage for the whole Murray-Darling basin if it did not receive sufficient water by October of that year.[49] Water restrictions were in place in many regions and cities of Australia in response to chronic shortages resulting from the 2008 drought.[50] In 2004 paleontologist Tim Flannery predicted that unless it made drastic changes the city of Perth, Western Australia, could become the world's first ghost metropolis—an abandoned city with no more water to sustain its population.[51] However, with increased rainfall in recent years, the water situation has improved.

In 2019 the drought and water resources minister of Australia David Littleproud, said, that he "totally accepts" the link between climate change and drought in Australia because he "live it". He says that the drought in Australia is already 8 years long. He called for a reduction in Greenhouse gas emission and massive installation of renewable energy. Former leader of the nationalists Barnaby Joyce said that if the drought became more fierce and dams will not be built, the coalition risk "political annihilation".[52]

Bushfires

In 2009, the Black Saturday bushfires erupted after a period of record hot weather resulting in the loss of 173 lives[53] and the destruction of 1,830 homes, and the newly found homelessness of over 7,000 people.[54]

Australian Greens leader Bob Brown said that the fires were "a sobering reminder of the need for this nation and the whole world to act and put at a priority the need to tackle climate change".[55] The Black Saturday Royal Commission recommended that "the amount of fuel-reduction burning done on public land each year should be more than doubled".[53]

In 2018, the fire season in Australia began in the winter. August 2018 was hotter and windier than the average. Those meteorologic conditions led to a drought in New South Wales. The Government of the state already gave more than $1 billion to help the farmers. The hotter and drier climate led to more fires. The fire seasons in Australia are lengthening and fire events became more frequent in the latest 30 years. These trends are probably linked to climate change.[56][57]

In 2019 bushfires linked to climate change created air pollution 11 times higher that the hazardous level in many areas of New South Wales. Many medical groups called to protect people from "public health emergency" and moving on from fossil fuels.[58]

Heavy smoke from fires reached Sydney delaying many flights and fires blocked roads around Sydney. The prime minister Scott Morrison experienced an hour's delay attempting to land in Sydney because of runway closures.[59]

From September 2019 to the end of January 2020, 34 people and one billion animals, possibly including entire species and subspecies died from the fires. Around 2,000 homes were destroyed.[60]

According to the United Nations Environment Programme the megafires in Australia in 2019–2020 are probably linked to climate change that created the unusually dry and hot weather conditions. This is part of a global trend. Brazil, United States, Russian federation, Democratic Republic of the Congo, face similar problems. By the second week of January the fires burned a territory of approximately 100,000 square kilometres close to the territory of England, killed one billion animals and caused big economic damage.[61]

Researchers claim that the exceptionally strong wildfires in 2019–2020, where impossible without climate change, that surely made temperature higher. More than one fifth of the Australian forests was burned in one season, what is completely unprecedented. They say that: "In the case of recent events in Australia, there is no doubt that the record temperatures of the past year would not be possible without anthropogenic influence, and that under a scenario where emissions continue to grow, such a year would be average by 2040 and exceptionally cool by 2060.".[62] Probably climate change also caused drier weather conditions in Australia by impacting Indian Ocean Dipole what also increase fires. In average, below 2% of Australian forests burn annually.[63] Climate change has increased the likelihood of the wildfires in 2019–2020 by at least 30%, but researchers said the result is probably conservative.[64]

Approximately 3 billion animals were killed or displaced by the bushfires in the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season what make them one of the worst natural disasters in recorded history. The chance of reaching the climatic conditions that fuels the fires became more than 4 times bigger since the year 1900 and will become 8 times more likely to occur if the temperature will rise by 2 degrees from the preindustrial level.[65]

Heatwaves

Since temperatures began to be recorded in 1910, they have increased by an average of 1 °C, with most of this change occurring from 1950 onwards. This period has seen the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events increase.[66]

Summer 2013–14 was warmer than average for the entirety of Australia.[67] Both Victoria and South Australia saw record-breaking temperatures. Adelaide recorded a total of 13 days reaching 40 °C or more, 11 of which reached 42 °C or more, as well as its fifth-hottest day on record—45.1 °C on 14 January. The number of days over 40 °C beat the previous record of summer 1897–1898, when 11 days above 40 °C were recorded. Melbourne recorded six days over 40 °C, while nighttime temperatures were much warmer than usual, with some nights failing to drop below 30 °C.[68] Overall, the summer of 2013–2014 was the third-hottest on record for Victoria, fifth-warmest on record for New South Wales, and sixth-warmest on record for South Australia.[67] This heatwave has been directly linked to climate change, which is unusual for specific weather events.[69]

Following the 2014 event, it was predicted that temperatures might increase by up to 1.5 °C by 2030.[70]

2015 was Australia's fifth-hottest year on record, continuing the trend of record-breaking high temperatures across the country.[71]

According to Australian Climate Council in 2017 Australia had its warmest winter on record, in terms of average maximum temperatures, reaching nearly 2 °C above average.[72]

Use of domestic airconditioners during severe heatwaves can double electricity demand, placing great stress on electricity generation and transmission networks, and lead to load shedding.[73]

January 2019 was the hottest month ever in Australia with average temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F).[74][75] The 2019–20 Australian bushfire season was Australia's worst bushfire season on record.[76]

Future effects of climate change on Australia

Analysis of future emissions trajectories indicates that, left unchecked, human emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) will increase several fold during the 21st century. Consequently, Australia's annual average temperatures are projected to increase 0.4–2.0 °C above 1990 levels by the year 2030, and 1–6 °C by 2070. Average precipitation in southwest and southeast Australia is projected to decline during this time period, while regions such as the northwest may experience increases in rainfall. Meanwhile, Australia's coastlines will experience erosion and inundation from an estimated 8–88 cm increase in global sea level. Such changes in climate will have diverse implications for Australia's environment, economy, and public health.[77] Future impacts will include more severe floods, droughts, and cyclones. Reaching zero emissions by 2050 possibly would not be enough for preventing 2 degrees temperature rise.[78]

Bushfires

Firefighting officials are concerned that the effects of climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of bushfires under even a "low global warming" scenario.[79] A 2006 report, prepared by CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Bushfire CRC, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, identified South Eastern Australia as one of the 3 most fire-prone areas in the world,[80] and concluded that an increase in fire-weather risk is likely at most sites over the next several decades, including the average number of days when the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index rating is very high or extreme. It also found that the combined frequencies of days with very high and extreme FFDI ratings are likely to increase 4–25% by 2020 and 15–70% by 2050, and that the increase in fire-weather risk is generally largest inland.[81]

Extreme weather events

The CSIRO predicts that a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius on the Australian continent could incur some of the following extreme weather occurrences, in addition to standard patterns:

- Wind speeds of tropical cyclones could intensify by 5 to 10%.[82]

- Tropical cyclone rainfall could increase by 20–30%.

- In 100 years, strong tides would increase by 12–16% along eastern Victoria's coast.[83]

- The forest fire danger indices in New South Wales and Western Australia would grow by 10% and the forest fire danger indices in south, central and north-east Australia would increase by more than 10%.[84][85]

Biodiversity and ecosystems

Australia has some of the world's most diverse ecosystems and natural habitats, and it may be this variety that makes them the Earth's most fragile and at-risk when exposed to climate change. The Great Barrier Reef is a prime example. Over the past 20 years it has experienced unparalleled rates of bleaching. Additional warming of 1 °C is expected to cause substantial losses of species and of associated coral communities.[77]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius will be:

- 97% of the Great Barrier Reef bleached annually.[86]

- 10–40% loss of principal habitat for Victoria and montane tropical vertebrate species.[87]

- 92% decrease in butterfly species' primary habitats.[88]

- 98% reduction in Bowerbird habitat in Northern Australia.[89]

- 80% loss of freshwater wetlands in Kakadu (30 cm sea level rise).[90]

Agriculture forestry and livestock

Small changes caused by global warming, such as a longer growing season, a more temperate climate and increased CO

2 concentrations, may benefit Australian crop agriculture and forestry in the short term. However, such benefits are unlikely to be sustained with increasingly severe effects of global warming. Changes in precipitation and consequent water management problems will further exacerbate Australia's current water availability and quality challenges, both for commercial and residential use.[77]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between 3 and 4 degrees Celsius will be:

- 32% possibility of diminished wheat production (without adaptation).[91]

- 45% probability of wheat crop value being beneath present levels (without adaptation).[91]

- 55% of primary habitat lost for Eucalyptus.[92]

- 25–50% rise in common timber yield in cool and wet parts of South Australia.[93]

- 25–50% reduction in common timber yield in North Queensland and the Top End.[93]

- 6% decrease in Australian net primary production (for 20% precipitation decrease)

- 128% increase in tick-associated losses in net cattle production weight.[94]

Water resources

Healthy and diverse vegetation is essential to river health and quality, and many of Australia's most important catchments are covered by native forest, maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Climate change will affect growth, species composition and pest incursion of native species and in turn, will profoundly affect water supply from these catchments. Increased re-afforestation in cleared catchments also has the prospect for water losses.[95]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between only 1 and 2 degrees Celsius will be:

- 12–25% reduction inflow in the Murray River and Darling River basin.[96]

- 7–35% reduction in Melbourne's water supply.[97]

Public health

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between only 1 and 2 degrees Celsius will be:[98]

- Southward spread of malaria receptive zones.

- Risk of dengue fever among Australians increases from 170,000 people to 0.75–1.6 million.

- 10% increase in diarrhoeal diseases among Aboriginal children in central Australia.

- 100% increase in a number of people exposed to flooding in Australia.

- Increased influx of refugees from the Pacific Islands.

Settlements and infrastructure

Global warming could lead to substantial alterations in climate extremes, such as tropical cyclones, heat waves and severe precipitation events. This would degrade infrastructure and raise costs through intensified energy demands, maintenance for damaged transportation infrastructure, and disasters, such as coastal flooding.[77]:5 In the coastal zone, sea level rise and storm surge may be more critical drivers of these changes than either temperature or precipitation.[77]:20

The CSIRO describes the additional impact on settlements and infrastructure for rises in temperature of only 1 to 2 degrees Celsius:

Human settlements

Climate change will have a higher impact on Australia's coastal communities, due to the concentration of population, commerce and industry. Climate modelling suggests that a temperature rise of 1–2 °C will result in more intense storm winds, including those from tropical cyclones.[99] Combine this with sea level rise, and the result is greater flooding, due to higher levels of storm surge and wind speed. Coleman, T. (2002) The impact of climate change on insurance against catastrophes. Proceedings of Living with Climate Change Conference. Canberra, 19 December.) Tourism of coastal areas may also be affected by coastal inundation and beach erosion, as a result of sea level rise and storm events. At higher levels of warming, coastal impacts become more severe with higher storm winds and sea levels.

Property

A report released in October 2009 by the Standing Committee on Climate Change, Water, Environment and the arts, studying the effects of a 1-metre sea level rise, possible within the next 30–60 years, concluded that around 700,000 properties around Australia, including 80,000 buildings, would be inundated. The collective value of these properties is estimated at $150 billion.[44]

A 1-metre sea level rise would have massive impacts, not just on property and associated economic systems, but in displacement of human populations throughout the continent. Queensland is the state most at risk due to the presence of valuable beachfront housing.[100]

Adelaide

Adelaide will get hotter and drier with rainfall predicted to decline 8% to 29% by 2090 and average temperature to increase between 4 and 0.9 degrees.[101] The number of days above 35 degrees will increase by 50% in 2090 and the number of days above 40 degrees will double.[102] Bringing it close to Northampton, Western Australia for temperature and Kadina, South Australia for rainfall.[101]

Sea levels will rise with predictions between 39 to 61 cm by 2090.[102] And extreme seas are predicted to rise as well, with the CSIRO predicting buildings in Port Adelaide would need to be raised by 50 to 81 cm to keep the amount of flooding incidents the same as recorded between 1986 and 2005.[102]

Brisbane

In a RCP 4.5 scenario Brisbane's temperature will be similar to that of Rockhampton today while rainfall will be closest to Gympie. The CSIRO predicts rainfall in Brisbane will fall between -23% (235 mm) and -4% (45.3 mm) annually by 2090 while temperature will rise between 4.2° and 0.9°.[101] The number of hot days and hot nights will double by 2050, with many people needing to avoid outdoor activity in summer. Further urban growth increases the number of hot nights even further.[103] Hot nights increase deaths amongst the elderly.[103] Rainfall will be deposited in less frequent more intense rain events, fire days will also get more frequent while frost days will decrease.[104] Sea levels are predicted to rise by 80 cm by 2100 and there will be more frequent sea level extremes.[104]

Darwin

In a RCP 4.5 scenario Darwin's temperature will be similar to that of Daly River now, with its rainfall most like that of Milikapiti. In a RCP 8.5 scenario, indicating higher greenhouse gas emissions, Darwin's temperature loses any close comparison in Australia being significantly hotter than every town in Australia is today (with the exclusion of Halls Creek in Autumn).

Sydney

Suburbs of Sydney like Manly, Botany,[105] Narrabeen,[105] Port Botany,[105] and Rockdale,[105] which lie on rivers like the Parramatta, face risks of flooding in low-lying areas such as parks (like Timbrell Park and Majors Bay Reserve), or massive expenses in rebuilding seawalls to higher levels. Sea levels are predicted to rise between 38 and 66 cm by 2090.[102]

Temperature in Sydney will increase between 0.9° and 4.2°, while rainfall will decrease between -23% and -4% by 2090.[101] Bringing Sydney's climate close to that of Beaudesert today (under a RCP 8.5 scenario).[101] Different parts of Sydney will warm differently with the greatest impact expected in Western Sydney and Hawkesbury, these areas can expect 5 to 10 additional hot days by 2030.[106] Similarly future rainfall patterns will be different to those today, with more rain expected to fall in summer and autumn and less expected in Winter and Spring. Fire danger days will increase in number by 2070.[107]

Melbourne

Sea levels are projected to rise between 0.37 cm and 0.59 cm at Williamstown (the closest covered point) by 2090.[102] At the higher end of this scale areas in and around Melbourne would be impacted. With some of the most vulnerable areas being the Docklands development and several marinas and berths in Port Phillip. Melbourne's climate will become similar in terms of total rainfall and average temperature to that of Dubbo today, with temperatures warming between 0.9° and 3.8° and total annual rainfall falling between -10% and -4% by 2090.[101] Rainfall patterns will also change with 20% less rainfall predicted during spring in 2050, which may impact the severity of summer bushfires.[108]

The increases in temperature and decrease in rainfall will have a series of follow on effects on the city, including a possible 35% reduction in trees in Melbourne by 2040.[108] And more frequent ambulance callouts and more deaths due to heatwaves. Climate change will cost Melbourne City $12.6bn by 2050.[108]

Perth

In 2090 Perth is predicted to have the rainfall of Yanchep today and the temperature of Geraldton using the RCP 4.5 scenario.[101] Rainfall is predicted to fall between -29% (-226 mm) and -8% (-66 mm) and temperature predicted to rise between 0.9° and 4°.[101] Perth may see the number of days above 35° increase from 28 per year on average to 36 in 2030, and to between 40 and 63 in 2090.[109] While frost days will decrease. Rainfall will increase in intensity while decreasing on average.[109] Drought days in the south west as a whole may increase by as much as 80% versus 20% for Australia.[109] The danger from fire will increase with more fire days for all of Western Australia.[109]

Hobart

By 2090 Hobart's climate will warm between 3.8° and 0.9°, rainfall will decline between 4% and 10%.[101] The temperature pattern will be similar to Port Lincoln while rainfall will be closer to Condoblin's today in a RCP 8.5 scenario.[101] Warm spells are likely to last longer and rainfall will trend to more intense rain events dumping less rain annually, increasing the risk of erosion and flooding.[110] Flooding on the Derwent river will become more regular and extreme with a current 1-in-100-year event being possibly a 2-to-6-year event in 2090.[110] Hobart's fire season will get longer.[110]

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef could be killed as a result of the rise in water temperature forecast by the IPCC. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the reef has experienced unprecedented rates of bleaching over the past two decades, and additional warming of only 1 °C is anticipated to cause considerable losses or contractions of species associated with coral communities.[77]

Lord Howe Island

The coral reefs of the World Heritage-listed Lord Howe Island could be killed as a result of the rise in water temperature forecast by the IPCC.[111] As of April 2019, approximately 5% of the coral is dead.[112]

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians have a millennia long history of responding and adapting to social and environmental changes. Indigenous Australians have a high level of situated traditional knowledge and historical knowledge about climate change.[113] However, the exposure of Indigenous Australians to climate change impacts is exacerbated by existing socio-economic disadvantages which are linked to colonial and post-colonial marginalisation.[4]

Some of these changes include a rise in sea levels, getting hotter and for a longer period of time, and more severe cyclones during the cyclone season.[8] Climate issues include wild fires, heatwaves, floods, cyclones, rising sea-levels, rising temperatures, and erosion.[5][6][7] The communities most affected by climate changes are those in the North where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 30% of the population.[8] Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander communities located in the coastal north are the most disadvantaged due to social and economic issues and their reliance on traditional land for food, culture, and health. This has begged the question for many community members in these regions, should they move away from this area or remain present.[8]

Many Aboriginal people live in rural and remote agricultural areas across Australia, especially in the Northern and Southern areas of the continent.[7][5] There are a variety of different climate impacts on different Aboriginal communities which includes cyclones in the Northern region and flooding in Central Australia which negatively impacts cultural sites and therefore the relationship between indigenous people and the places that hold their traditional knowledge.[6] Other effects include sea level rise, loss of land and hunting ground, changes in fire regimes, increased severity and duration of wet and dry seasons as well as reduced numbers of animals in the sea, rivers and creeks.[6]

Vulnerability

The vulnerability comes from remote location where indigenous groups live, lower socio-economic status, and reliance of natural systems for economic needs.[4] Disadvantages which are compounding Indigenous peoples vulnerability to climate change include inadequate health and educational services, limited employment opportunities as well as insufficient infrastructure. Top down institutions have also restricted Indigenous Australians ability to contribute to climate policy frameworks and have their culture and practices recognised.[6]

.jpg.webp)

Many of the economic, political, and social-ecological issues present in indigenous communities are long term effects from colonialism and the continued marginalization of these communities. These issues are aggravated by climate change and environmental changes in their respective regions.[7][114] Indigenous people are seen as particularly vulnerable to climate change because they already live in poverty, poor housing and have poor educational and health services, other socio-political factors place them at risk for climate change impacts.[6] Indigenous people have been portrayed as victims and as vulnerable populations for many years by the media.[7][114] Aboriginal Australians believe that they have always been able to adapt to climate changes in their geographic areas.[6]

Many communities have argued for more community input into strategies and ways to adapt to climate issues instead of top down approaches to combating issues surrounding environmental change.[115][8] This includes self-determination and agency when deciding how to respond to climate change including proactive actions.[8] Indigenous people have also commented on the need to maintain their physical and mental well being in order to adapt to climate change which can be helped through the kinship relationships between community members and the land they occupy.[115]

In Australia, Aboriginal people have argued that in order for the government to combat climate change, their voices must be included in policy making and governance over traditional land.[114][7][115] Much of the government and institutional policies related to climate change and environmental issues in Australia has been done so through a top down approach.[116] Indigenous communities have stated that this limits and ignores Aboriginal Australian voices and approaches.[114][116] Due to traditional knowledge held by these communities and elders within those communities, traditional ecological knowledge and frameworks are necessary to combat these and a variety of different environmental issues.[7][114]

Heat and drought

Fires and droughts in Australia, including the Northern regions, occur mostly in savannas because of current environmental changes in the region. The majority of the fire prone areas in the savanna region are owned by Aboriginal Australian communities, the traditional stewards of the land.[117] Aboriginal Australians have traditional landscape management methods including burning and clearing the savanna areas which are the most susceptible to fires.[117] Traditional landscape management declined in the 19th century as Western landscape management took over.[117] Today, traditional landscape management has been revitalized by Aboriginal Australians, including elders. This traditional landscape practices include the use of clearing and burning to get rid of old growth. Though the way in which indigenous communities in this region manage the landscape has been banned, Aboriginal Australian communities who use these traditional methods actually help in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[117]

Impact of climate change on health

Increased temperatures, wildfires, and drought are major issues in regard to the health of Aboriginal Australian communities. Heat poses a major risk to elderly members of communities in the North.[118] This includes issues such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion.[118] Many of the rural indigenous communities have faced thermal stress and increased issues surrounding access to water resources and ecological landscapes. This impacts the relationship between Aboriginal Australians and biodiversity, as well as impacts social and cultural aspects of society.[118]

Aboriginal Australians who live in isolated and remote traditional territories are more sensitive than non-indigenous Australians to changes that effect the ecosystems they are a part of. This is in large part due to the connection that exists between their health (including physical and mental), the health of their land, and the continued practice of traditional cultural customs.[4] Aboriginal Australians have a unique and important relationship with the traditional land of their ancestors. Because of this connection, the dangerous consequences of climate change in Australia has resulted in a decline in health including mental health among an already vulnerable population.[118][119] In order to combat health disparities among these populations, community based projects and culturally relevant mental and physical health programs are necessary and should include community members when running these programs.[119]

Traditional knowledge

.jpg.webp)

Indigenous people have always responded and adapted to climate change, including indigenous people of Australia.[6] Aboriginal Australian people have existed in Australia for tens of thousands of years. Due to this continual habitation, Aboriginal Australians have observed and adapted to climatic and environmental changes for millennia which uniquely positions them to be able to respond to current climate changes.[6][120] Though these communities have shifted and changed their practices overtime, traditional ecological knowledge exists that can benefit local and indigenous communities today.[120] This knowledge is part of traditional cultural and spiritual practices within these indigenous communities. The practices are directly tied to the unique relationship between Aboriginal Australians and their ecological landscapes. This relationship results in a socio-ecological system of balance between humans and nature [116] Indigenous communities in Australia have specific generational traditional knowledge about weather patterns, environmental changes and climatic changes.[115][121][118] These communities have adapted to climate change in the past and have knowledge that non-Indigenous people may be able to utilize to adapt to climate change currently and in the future.[103]

Indigenous people have not been offered many opportunities or provided with sufficient platforms to influence and contribute their traditional knowledge to the creation of current international and local policies associated to climate change adaptation.[122] Although, Indigenous people have pushed back on this reality, by creating their own platforms and trying to be active members in the conversation surrounding climate change including at international meetings.[123] Specifically, Indigenous people of Australia have traditional knowledge to adapt to increased pressures of global environmental change.[115]

Though some of this traditional knowledge was not utilised and conceivably lost with the introduction of white settlers in the 18th century, recently communities have begun to revitalize these traditional practices.[117] Australian Aboriginal traditional knowledge includes language, cultural, spiritual practices, mythology and land management.[121][120]

Responses to climate change

Indigenous knowledge has been passed down through the generations with the practice of oral tradition.[7] Given the historical relationship between the land and the people and the larger ecosystem Aboriginal Australians choose to stay and adapt in similar ways to their ancestors before them.[115] Aboriginal Australians have observed short and long term environmental changes and are highly aware of weather and climate changes.[121] Recently, elders have begun to be utilised by indigenous and non-indigenous communities to understand traditional knowledge related to land management.[114] This includes seasonal knowledge means indigenous knowledge pertaining to weather, seasonal cycles of plants and animals, and land and landscape management.[120][116] The seasonal knowledge allows indigenous communities to combat environmental changes and may result in healthier social-ecological systems.[116] Much of traditional landscape and land management includes keeping the diversity of floral and fauna as traditional foodways.[120] Ecological calendars is one traditional framework used by Aboriginal Australian communities. These ecological calendars are way for indigenous communities to organize and communicate traditional ecological knowledge.[120] The ecological calendars includes seasonal weather cycles related to biological, cultural, and spiritual ways of life.[120]

Adaptation

Mitigation

See also

- Beyond Zero Emissions

- Biofuel in Australia

- Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme

- Climate Code Red

- Climate Group

- Climate Institute of Australia

- Climate of Australia

- Drought in Australia

- Environmental issues in Australia

- Greenhouse Mafia

- Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy

- Living in the Hothouse: How Global Warming Affects Australia, a 2005 book by Ian Lowe

- Effects of global warming on oceans

- El Niño–Southern Oscillation

- IPCC Fifth Assessment Report

- Water restrictions in Australia

References

- Lindenmayer, David; Dovers, Stephen; Morton, Steve, eds. (2014). Ten Commitments Revisited. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486301676.

- Johnston, Tim (3 October 2007). "Climate change becomes urgent security issue in Australia". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Pittock, Barrie, ed. (2003). Climate Change: An Australian Guide to the Science and Potential Impacts (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia: Australian Greenhouse Office. ISBN 978-1-920840-12-9.

- Green, Donna (November 2006). "Climate Change and Health: Impacts on Remote Indigenous Communities in Northern Australia". S2CID 131620899. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Green, Donna (November 2006). "Climate Change and Health: Impacts on Remote Indigenous Communities in Northern Australia". S2CID 131620899. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nursey-Bray, Melissa; Palmer, R.; Smith, T. F.; Rist, P. (4 May 2019). "Old ways for new days: Australian Indigenous peoples and climate change". Local Environment. 24 (5): 473–486. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1590325. ISSN 1354-9839.

- Ford, James D. (July 2012). "Indigenous Health and Climate Change". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (7): 1260–1266. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3477984. PMID 22594718.

- Zander, Kerstin K.; Petheram, Lisa; Garnett, Stephen T. (1 June 2013). "Stay or leave? Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia". Natural Hazards. 67 (2): 591–609. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0591-4. ISSN 1573-0840. S2CID 128543022.

- "Quarterly Update of Australia's National Greenhouse Gas Inventory for March 2019".

- "Quarterly Update of Australia's National Greenhouse Gas Inventory for March 2019".

- "Australia's emissions to start falling thanks to renewables boom, researchers say". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Australasia".

- Flannery, Tim, The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australian Lands and People; p. 115 ISBN 0-8021-3943-4

- Water Research Foundation of Australia; 1975 symposium: the 1973-4 floods in rural and urban communities; seminar held in August 1976 by the Victorian Branch of the Water Research Foundation of Australia.

- Allen, R. J.; The Australasian Summer Monsoon, Teleconnections, and Flooding in the Lake Eyre Basin; pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-909112-09-6

- Bourke, Patricia; Brockwell, Sally; Faulkner, Patrick and Meehan, Betty; "Climate variability in the mid to late Holocene Arnhem Land region, North Australia: archaeological archives of environmental and cultural change" in Archaeology in Oceania; 42:3 (October 2007); pp. 91–101.

- Water Research Foundation of Australia; 1975 symposium

- Lough, J. M. (2007), "Tropical river flow and rainfall reconstructions from coral luminescence: Great Barrier Reef, Australia", Paleoceanography, 22, PA2218, doi:10.1029/2006PA001377.

- Warner, R. F.; "The impacts of flood- and drought-dominated regimes on channel morphology at Penrith, New South Wales, Australia". IAHS Publ. No. 168; pp. 327–338, 1987.

- Green, H.J.; Results of rainfall observations made in South Australia and the Northern Territory: including all available annual rainfall totals from 829 stations for all years of recording up to 1917, with maps and diagrams: also appendices, presenting monthly and yearly meteorological elements for Adelaide and Darwin; published 1918 by Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology

- Gibbs, W.J. and Maher, J. V.; Rainfall deciles as drought indicators; published 1967 by Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Hunt, H.A. Results of rainfall observations made in Queensland: including all available annual rainfall totals from 1040 stations for all years of record up to 1913, together with maps and diagrams; published 1914 by Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology

- "Commentary on rainfall probabilities based on phases of the SOI". www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au. Department of Environment and Resource Management. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2008.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ashcroft, Linden; Gergis, Joëlle; Karoly, David John (November 2014). "A historical climate dataset for southeastern Australia, 1788-1859". Geoscience Data Journal. 1 (2): 158–178. Bibcode:2014GSDJ....1..158A. doi:10.1002/gdj3.19.

- Foley, J.C.; Droughts in Australia: review of records from earliest years of settlement to 1955; published 1957 by Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Allan, R.J.; Lindesay, J. and Parker, D.E.; El Niño, Southern Oscillation and Climate Variability; p. 70. ISBN 0-643-05803-6

- Soils and landscapes near Narrabri and Edgeroi, NSW, with data analysis using fuzzy k-means

- Fewer frosts. Bureau of Meteorology.

- "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2009". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2011". Bom.gov.au. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- "Annual climate statement of 2014". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "2014 was Australia's warmest year on record: BoM". ABC Online. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- CSIRO (2006). Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- CSIRO (2007), Climate change in Australia: Technical report 2007, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra; Preston, B. and Jones, R. (2006), Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A consultancy report for the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change, CSIRO, Canberra.

- http://climatecommission.gov.au/resources/commission-reports/ Climate Commission reports.

- Peel, Jacquiline; Osofsky, Hari (2015). Climate Change Litigation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781107036062.

- The Critical Decade: Extreme Weather Climate Commission Australia.

- "key facts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2013.

- Climate change making extreme events worse in Australia – report The Guardian 2.4.2013

- Sivakumar, Mannava; Motha, Raymond (2007). Managing Weather and Climate Risks in Agriculture. Berlin: Springer. pp. 109. ISBN 9783540727446.

- DCC (2009), Climate Change Risks to Australia's coasts, Canberra.

- Glavovic, Bruce; Kelly, Mick; Kay, Mick; Travers, Aibhe (2014). Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 9781482288582.

- Australia's Low Pollution Future: The Economics of Climate Change Mitigation Archived 18 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Herald Sun, "Victoria's Stormy Forecast", Oct, 28, 2009

- Karp, Paul (17 December 2019). "Climate change has cut Australian farm profits by 22% a year over past 20 years, report says". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Anderson, Deb (2014). Endurance. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486301201.

- "Hasta la vista El Nino – but don't hold out for 'normal' weather just yet". The Conversation. 28 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- "Regional Rainfall Trends". Commonwealth of Australia Bureau of Meteorology. 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Australian rivers 'face disaster', BBC News

- Saving Australia's water, BBC News

- Metropolis strives to meet its thirst, BBC News

- Katharine Murphy, Katharine (6 October 2019). "Water resources minister 'totally' accepts drought linked to climate change". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Black Saturday Royal Commission". The Age. Melbourne. 31 July 2010.

- "More than 1,800 homes destroyed in Vic bushfires". ABC News Australia. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Walsh, Bryan (9 February 2009). "Why Global Warming May Be Fueling Australia's Fires". Time. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- Price, Owen (17 August 2018). "Drought, wind and heat: Bushfire season is starting earlier and lasting longer". ABC News. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Woodburn, Joanna (8 August 2018). "NSW Government says entire state in drought, new DPI figures reveal full extent of big dry". ABC News. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Readfearn, Graham (15 December 2019). "Governments must act on public health emergency from bushfire smoke, medical groups say". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Higgins, Eoin (23 December 2019). "Everything Is Burning': Australian Inferno Continues, Choking off Access to Cities Across Country". Ecowatch. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Newcomb, Alyssa (6 January 2020). "Bindi Irwin wishes dad 'was here right now' amid Australia wildfires". Today. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "Are "megafires" the new normal?". United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Cox, Lisa (24 February 2020). "'Unprecedented' globally: more than 20% of Australia's forests burnt in bushfires". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Bushfires burned a fifth of Australia's forest: study". Phys. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Phillips, Nicky (4 March 2020). "Climate change made Australia's devastating fire season 30% more likely". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00627-y. PMID 32152593. S2CID 212651929. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Readfearn, Graham; Morton, Adam (28 July 2020). "Almost 3 billion animals affected by Australian bushfires, report shows". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "State of the Climate 2014". Bureau of Meteorology. 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Australia in Summer 2013–14". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- "Melbourne in Summer 2014". Buearu of Meteorology. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Gillis, Justin (29 September 2014). "Scientists Trace Extreme Heat in Australia to Climate Change". New York Times. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "CSIRO report says Australia getting hotter with more to come". ABC Online. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Annual Climate Report 2015". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Hot and Dry: Australia's Weird Winter BY LESLEY HUGHES 18.09.2017

- Electricity supplies under pressure due to heatwave, energy market operator warns ABC News, 29 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Cox, Lisa; Watts, Jonathan (2 February 2019). "Australia's extreme heat is sign of things to come, scientists warn". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Hannam, Peter; Clun, Rachel (2 February 2019). "'Dome of hot air': Australia blows away heat records". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Australia fires: Life during and after the worst bushfires in history". BBC News. 28 April 2020.

- Preston, B. L.; Jones, R. N. (2006). Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A consultancy report for the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change (PDF). CSIRO.

- Perkins, Miki (13 November 2020). "Climate change is already here: major scientific report". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Marshall, Peter (12 February 2009). "Face global warming or lives will be at risk". Melbourne: The Age Newspaper. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- "CLIMATE CHANGE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE MANAGEMENT OF BUSHFIRE" (PDF). Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre. September 2006. p. 4. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- K. Hennessy, C. Lucas, N. Nicholls, J. Bathols, R. Suppiah & J. Ricketts (December 2005). "Climate change impacts on fire-weather in south-east Australia" (PDF). CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Bushfire CRC and Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 13 February 2009.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- McInnes, K.L., Walsh, K.J.E., Hubbert, G.D., and Beer, T. (2003) Impact of sea-level rise and storm surges on a coastal community. Natural Hazards 30, 187–207

- McInnes, K.L., Macadam, I., Hubbert, G.D., Abbs, D.J., and Bathols, J. (2005) Climate Change in Eastern Victoria, Stage 2 Report: The Effect of Climate Change on Storm Surges. A consultancy report undertaken for the Gippsland Coastal Board by the Climate Impacts Group, CSIRO Atmospheric Research

- Williams, A.A., Karoly, D.J., and Tapper, N. (2001) The sensitivity of Australian fire danger to climate change. Climatic Change 49, 171–191

- Cary, G.J. (2002) Importance of changing climate for fire regimes in Australia. In: R.A. Bradstock, J.E. Williams and A.M. Gill (eds), Flammable Australia: The Fire Regimes and Biodiversity of A Continent, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, pp. 26–46.

- Jones, R.N. (2004) Managing Climate Change Risks, in Agrawala, S. and Corfee-Morlot, J. (eds.), The Benefits of Climate Change Policies: Analytical and Framework Issues, OECD, Paris, 249–298.

- Brereton, R., Bennett, S. and Mansergh, I. (1995) Enhanced greenhouse climate change and its potential effect on selected fauna of south-eastern Australia: a trend analysis. Biological Conservation, 72, 39–354.

- Beaumont, L.J., and Hughes, L. (2002) Potential changes in the distributions of latitudinally restricted Australian butterfly species in response to climate change. Global Change Biology 8(10), 954–971.

- Hilbert, D.W., Bradford, M., Parker, T., and Westcott, D.A. (2004) Golden bowerbird (Prionodura newtonia) habitat in past, present and future climates: predicted extinction of a vertebrate in tropical highlands due to global warming. Biological Conservation, 116, 367

- Hare, W., (2003) Assessment of Knowledge on Impacts of Climate Change – Contribution to the Specification of Art. 2 of the UNFCCC, WGBU, Berlin,

- Howden, S.M., and Jones, R.N. (2001) Costs and benefits of CO

2 increase and climate change on the Australian wheat industry, Australian Greenhouse Office, Canberra, Australia. - Hughes, L., Cawsey, E.M., Westoby, M. (1996) Geographic and climatic range sizes of Australian eucalyptus and a test of Rapoport's rule. Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters 5, 128–142.

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. (1999) The effect of climate change on forest growth in Australia. In: Impacts of Global Change on Australian Temperate Forests. S.M. Howden and J.T. Gorman (eds), Working Paper Series, 99/08, pp. 62–68 (CSIRO Wildlife and Ecology, Canberra).

- White, N.A., Sutherst, R.W., Hall, N., and Wish-Wilson, P. (2003) The vulnerability of the Australian beef industry to impacts of the cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) under climate change. Climatic Change 61, 157–190.

- Herron, N., Davis, R., and Jones, R.N. (2002) The effects of large-scale afforestation and climate change on water allocation in the Macquarie River Catchment, NSW, Australia. Journal of Environmental Management 65, 369–381.

- Arnell, N.W. (1999) Climate change and global water resources. Global Environmental Change 9, S31–S46.

- Howe, C., Jones, R.N., Maheepala, S., and Rhodes, B. (2005) Implications of Climate Change for Melbourne's Water Resources. Melbourne Water, Melbourne, 26 pp.

- McMichael, A. J., et al. (2003) Human Health and Climate Change in Oceania: A Risk Assessment. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 128 pp.)

- Coleman, T. (2002) The impact of climate change on insurance against catastrophes. Proceedings of Living with Climate Change Conference. Canberra, 19 December.

- "At a glance: Coastal erosion & Australia". SBS. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- CSIRO, Department of Environment, BOM. "Analogues Explorer". Climate Change In Australia: Analogues Explorer.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- CSIRO, Department of Environment, BOM (2017). "Climate change in australia technical report" (PDF). Climate Change in Australia.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "'This isn't a path we want to be on': Temperature rises will make city life difficult, report finds". www.abc.net.au. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Queensland Government. "Climate Change in the South East Queensland Region" (PDF).

- Most at risk: Study reveals Sydney's climate change 'hotspots' – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- NSW Department of Environment. "Climate Change Impact Reports: Urban Heat NSW" (PDF).

- Department of Environment NSW. "Climate change snapshots: Sydney" (PDF). Climate Change, Department of Environment.

- "Climate change impacts on Melbourne - City of Melbourne". www.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Climate projections for Western Australia". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Hobart Climate Change Information for Decision Making" (PDF). Hobartcity.com. City of Hobart.

- Clarke, Sarah (24 March 2010). "Bleaching leaves Lord Howe reef 'on knife edge'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Robbo, Luisa (5 April 2019). "Coral bleaching reaches World Heritage-listed Lord Howe Island Marine Park". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Nursey-Bray, Melissa; Palmer, Robert (1 March 2018). "Country, climate change adaptation and colonisation: insights from an Indigenous adaptation planning process, Australia". Heliyon. 4 (3): e00565. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00565. ISSN 2405-8440. PMC 5968082. PMID 29862336.

- Belfer, Ella; Ford, James D.; Maillet, Michelle (2017). "Representation of Indigenous peoples in climate change reporting". Climatic Change. 145 (1): 57–70. Bibcode:2017ClCh..145...57B. doi:10.1007/s10584-017-2076-z. ISSN 0165-0009. PMC 6560471. PMID 31258222.

- Petheram, L.; Zander, K. K.; Campbell, B. M.; High, C.; Stacey, N. (1 October 2010). "'Strange changes': Indigenous perspectives of climate change and adaptation in NE Arnhem Land (Australia)". Global Environmental Change. 20th Anniversary Special Issue. 20 (4): 681–692. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.05.002. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Leonard, Sonia; Parsons, Meg; Olawsky, Knut; Kofod, Frances (1 June 2013). "The role of culture and traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia". Global Environmental Change. 23 (3): 623–632. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.012. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Russell-Smith, Jeremy; Cook, Garry D.; Cooke, Peter M.; Edwards, Andrew C.; Lendrum, Mitchell; Meyer, CP (Mick); Whitehead, Peter J. (2013). "Managing fire regimes in north Australian savannas: applying Aboriginal approaches to contemporary global problems". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 11 (s1): e55–e63. doi:10.1890/120251. ISSN 1540-9309.

- Horton, Graeme; Hanna, Liz; Kelly, Brian (2010). "Drought, drying and climate change: Emerging health issues for ageing Australians in rural areas". Australasian Journal on Ageing. 29 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00424.x. ISSN 1741-6612. PMID 20398079. S2CID 6984028.

- Berry, Helen L.; Butler, James R. A.; Burgess, C. Paul; King, Ursula G.; Tsey, Komla; Cadet-James, Yvonne L.; Rigby, C. Wayne; Raphael, Beverley (6 August 2010). "Mind, body, spirit: co-benefits for mental health from climate change adaptation and caring for country in remote Aboriginal Australian communities". New South Wales Public Health Bulletin. 21 (6): 139–145. doi:10.1071/NB10030. ISSN 1834-8610. PMID 20637171.

- Prober, Suzanne; O'Connor, Michael; Walsh, Fiona (17 May 2011). "Australian Aboriginal Peoples' Seasonal Knowledge: a Potential Basis for Shared Understanding in Environmental Management". Ecology and Society. 16 (2). doi:10.5751/ES-04023-160212. ISSN 1708-3087.

- Green, Donna; Billy, Jack; Tapim, Alo (1 May 2010). "Indigenous Australians' knowledge of weather and climate". Climatic Change. 100 (2): 337–354. Bibcode:2010ClCh..100..337G. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9803-z. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 287380.

- Petheram, L.; Zander, K. K.; Campbell, B. M.; High, C.; Stacey, N. (1 October 2010). "'Strange changes': Indigenous perspectives of climate change and adaptation in NE Arnhem Land (Australia)". Global Environmental Change. 20th Anniversary Special Issue. 20 (4): 681–692. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.05.002. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Etchart, Linda (22 August 2017). "The role of indigenous peoples in combating climate change". Palgrave Communications. 3 (1). doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.85. ISSN 2055-1045.

Further reading

External links

- Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency – Australian Government

- Climate Action Network Australia – the Australian branch of a worldwide network of NGO's

- Range Extension Database and Mapping Project, Australia – ecological monitoring project in the marine environment