Fatimid art

Fatimid art refers to [ artifacts and architecture from the Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), was in Arab empire principally in Egypt and North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate was initially established in the Maghreb, with its roots in a ninth-century Shia Ismailist Many monuments survive in the Fatimid cities founded in North Africa, starting with Mahdia, on the Tunisian coast, the principal city prior to the conquest of Egypt in 969 and the building of al-Qahira, the "City Victorious", now part of modern-day Cairo. The period was marked by a prosperity amongst the upper echelons, manifested in the creation of opulent and finely wrought objects in the decorative arts, including carved rock crystal, lustreware and other ceramics, wood and ivory carving, gold jewelry and other metalware, textiles, books and coinage. These items not only reflected personal wealth, but were used as gifts to curry favour abroad. The most precious and valuable objects were amassed in the caliphal palaces in al-Qahira. In the 1060s, following several years of drought during which the armies received no payment, the palaces were systematically looted, the libraries largely destroyed, precious gold objects melted down, with a few of the treasures dispersed across the medieval Christian world. Afterwards Fatimid artifacts continued to be made in the same style, but were adapted to a larger populace using less precious materials.

In 1067-68 the great treasury of the Fatimids was ransacked when the troops rebelled and demanded to be paid. The stories of this plundering mention not only great quantities of pearls and jewels, crowns, swords, and other imperial accoutrements but also many objects in rare materials and of enormous size. Eighteen thousand pieces of rock crystal and cut glass were swiftly looted from the palace, and twice as many jewelled objects; also large numbers of gold and silver knives all richly set with jewels; valuable chess and backgammon pieces; various types of hand mirrors, skilfully decorated; six thousand perfume bottles in gilded silver; and so on. More specifically, we learn of enormous pieces of rock crystal inscribed with caliphal names; of gold animals encrusted with jewels and enamels; of a large golden palm tree; and even of a whole garden partially gilded and decorated with niello. There was also an immensely rich treasury of furniture, carpets, curtains, and wall coverings, many embroidered in gold, often with designs incorporating birds and quadrupeds, kings and their notables, and even a whole range of geographical vistas.Relatively few of these objects have survived, most of them very small; but the finest are impressive enough to lend substance to the vivid picture painted in the historical accounts of this vanished world of luxury.

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Rock crystal ewers

Rock crystal ewers are pitchers carved from a single block of rock crystal. They were made by Islamic Fatimid artisans and are considered to be amongst the rarest objects in Arab art.[1] There are a few that survived and are now in collections across Europe. They are often in cathedral treasuries, where they were rededicated after being captured from their original Islamic settings. Made in Egypt in the late 10th century, the ewer pictured is exquisitely decorated with fantastic birds, beasts and twisting tendrils. The Treasure of Caliph Mostansir-Billah at Cairo, which was destroyed in 1062, apparently contained 1800 rock crystal vessels.

Great skill was required to hollow out the raw rock crystal without breaking it and to carve the delicate, often very shallow, decoration.

The Fatimids produced a variety of beautifully crafted works of art resulting in textiles, ceramics, woodwork, jewelry, and importantly rock crystals. Among the many wonders that people have discovered in Fatimid treasuries, objects were strictly carved from rock crystal. Rock crystal is made up of pure quartz crystal and was shaped by skillful craftsmen whom the Fatimids valued greatly. “Of all the rock crystal objects manufactured by Fatimid artisans, the Fatimid rock crystal ewers are considered among the rarest and most valuable objects in the entire sphere of Islamic art. Only five were known to exist before the extraordinary appearance of an ewer in a provincial British auction in 2008 which was later sold at Christie’s last October. It was the first time one has ever known to have appeared at auction. The last one to surface on the market was purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1862.”[2] The treasury of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice has two ewers. An additional rock crystal ewer was found in the treasury of Abbey of Saint Denis in Paris. “The extant rock crystal objects with no identifying inscription on them appear to be types of containers, either goblets for drinking or ewers and basins for holding liquids, perhaps for washing the hands of the guests after a meal."[2] Over the centuries, many magical properties or benefits were deemed to be associated with objects made using rock crystal.

Between the tenth and eleventh centuries, Egypt produced most of the rock crystals that were located in the medieval treasuries of the West, several smaller pieces were discovered in Spain that reached the peninsula during the Caliphate of Cordoba. The required way to create rock crystals is to hollow out a piece of crystal without damaging the decoration. Once the rock crystals are ready to be designed, the carvings usually depict floral or animal themes, especially birds and lions. Rock crystals are periodically gold or made up of precious stones. Rock crystal vessels has a pear-shaped body, beaked rim, and a handle, which originally has a vertical thumb piece that connects the rim of the ewer to the lower part of the body. The designs on the ewer goes around the neck and down the body and onto its handle. "All of the details are drilled and cut with great skill, including the texturing in the form of lines and dots covering the bird and animal and the leaves of the arabesque patterns."[3] A number of rock crystal ewers were used in church treasuries in Europe.

Two rock-crystal vessels, the first in St. Petersburg and S. Marco Venice are the last two remaining medieval Islamic rock crystal ewers. “The two lamps have a form very different from the common Islamic globular vase-like lamp. This unusual shape can be explained in part by the material from which they were made: the high price of rock crystal and the proficiency required of the carver meant that the manufacture of these precious objects was only patronized by royalty or nobility.”[4] The lamp from St. Petersburg goes back to the boat-shaped early Christian metal lamps. The S. Marco lamp is a rare ewer and may appear in medieval Islamic manuscript illustrations. Our knowledge of contemporary Fatimid glass is equally-if not more- problematic. "Several extraordinary relief-cut or cameo glass ewers are so similar in size, shape, and decoration to the crystal ewers that some scholars have attributed them to Fatimid Egypt.”[5] Rock crystals are designed to emulate metal vessels of pre-Islamic and early Islamic era.

Ultimately, rock crystals during the Fatimid period display decorative arts. Many rock crystals and their carvers have shown immense skill in their work treasured by caliphs. The tradition of carving rock crystal in Egypt was masterful, the purest crystals were imported from Arabia and Basra, and the islands of Zanj in East Africa. Nasir-i-Khusraw, Persian poet and philosopher states, "Yemen was a source of pure rock crystal, and that prior to discovering this source, lesser quality rock crystal was imported from the Maghreb and India.”[6] Rock crystals has provided valuable insight into the advancement of traditional crafts that are being presented today.

Fatimid architecture

In architecture, the Fatimids followed Tulunid techniques and used similar materials, but also developed those of their own. In Cairo, their first congregational mosque was al-Azhar mosque ("the splendid") founded along with the city (969–973), which, together with its adjacent institution of higher learning (al-Azhar University), became the spiritual center for Ismaili Shia. The Mosque of al-Hakim (r. 996–1013), an important example of Fatimid architecture and architectural decoration, played a critical role in Fatimid ceremonial and procession, which emphasized the religious and political role of the Fatimid caliph. Besides elaborate funerary monuments, other surviving Fatimid structures include the Aqmar Mosque (1125)[7] as well as the monumental gates for Cairo's city walls commissioned by the powerful Fatimid emir and vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1073–1094).

Gallery

Rock crystal ewer, Victoria and Albert Museum

Rock crystal ewer, Victoria and Albert Museum

.jpg.webp) 11th century gold armlet from Syria. Freer Gallery of Art

11th century gold armlet from Syria. Freer Gallery of Art Lustre ware cup with eagle. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lustre ware cup with eagle. Metropolitan Museum of Art Ceramic bowl, Bardo National Museum

Ceramic bowl, Bardo National Museum Carved stone column in the al-Aqmar Mosque in Cairo

Carved stone column in the al-Aqmar Mosque in Cairo.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Minbar of the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron, originally commissioned by the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali in 1091 for the shrine of Husayn in Ascalon.

The Minbar of the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron, originally commissioned by the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali in 1091 for the shrine of Husayn in Ascalon. Carved and engraved ivory panel with hunters, Louvre

Carved and engraved ivory panel with hunters, Louvre 12th century linen tapestry with silk embroidery, Royal Ontario Museum

12th century linen tapestry with silk embroidery, Royal Ontario Museum

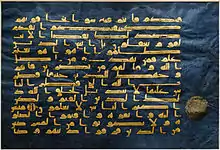

Page from the Blue Qur'an, Gold and silver leaf on indigo-dyed parchment, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Page from the Blue Qur'an, Gold and silver leaf on indigo-dyed parchment, Metropolitan Museum of Art 10th century gold dinar, Caliphate of al-Muizz Lideenillah, British Museum

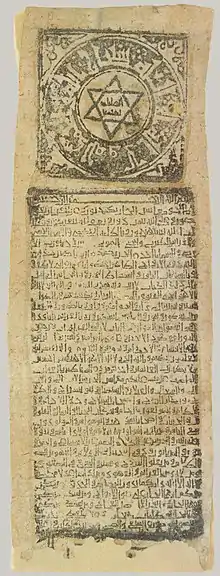

10th century gold dinar, Caliphate of al-Muizz Lideenillah, British Museum 10th century leather bookbinding, Kairouan

10th century leather bookbinding, Kairouan 10th-11th century illustration of rooster, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

10th-11th century illustration of rooster, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art 11th-12th century illustration of hare from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

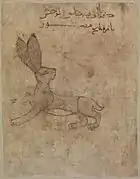

11th-12th century illustration of hare from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art 11th-12th century illustration of lion from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art

11th-12th century illustration of lion from lost bestiary, Fustat, Metropolitan Museum of Art 12th-13th century copy of 11th century world map from "Book of Curiosities", Bodleian Library

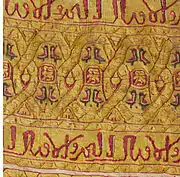

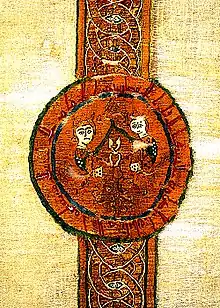

12th-13th century copy of 11th century world map from "Book of Curiosities", Bodleian Library So-called "Veil of St. Anne", 1096/97, Apt, Vaucluse

So-called "Veil of St. Anne", 1096/97, Apt, Vaucluse

Notes

- Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art

- "Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art". Simerg - Insights from Around the World. 2009-05-21. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- "Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum - object_ISL_uk_Mus02_1_en". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- Shalem, Avinoam (2011). Fountains of Light. p. 2.

- Rosser-Owen, M. (2009-01-01). "Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt * BY JONATHAN M. BLOOM". Journal of Islamic Studies. 20 (1): 114–118. doi:10.1093/jis/etn081. ISSN 0955-2340.

- "Fatimid Lustre: Historical Introduction". islamicceramics.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- Doris Behrens-Abouseif (1992), Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction, BRILL, p. 72

- This ewer, inscribed with the name of Husain ibn Jawhar,a general of the Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, was accidentally dropped by an assistant in the museum in 1998 and shattered beyond repair.

References

History of art

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2007), Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic art and architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-13542-4

- Jackson, Anna (ed.) (2001). V&A: A Hundred Highlights. V&A Publications.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ellis, Marianne (2001), Embroideries and samplers from Islamic Egypt, Ashmolean Museum, ISBN 1-85444-135-3

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009), The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture, Volumes 1–3, Oxford University Press

- Barrucand, Marianne, ed. (1999), L'Égypte fatimide: son art et son histoire : actes du colloque organisé à Paris les 28, 29 et 30 mai 1998, Presses de l'université de Paris-Sorbonne

- Yeomans, Richard (2006), The art and architecture of Islamic Cairo, Garnet, ISBN 1-85964-154-7

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins, Marilyn (2001), Islamic art and architecture 650-1250, Pelican history of art, 51 (2nd ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08869-8

- Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D., eds. (2000), Glory of Byzantium: Arts and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-300-08616-4

- Qaddumī, Ghādah Ḥijjāwī (1996), Book of gifts and rarities, Harvard Middle Eastern monographs, 29, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-932885-13-6t

History

- Hoffman, Eva Rose F., ed. (2007), Late antique and medieval art of the Mediterranean world, Blackwell anthologies in art history, 5, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1-4051-2072-X

- Brett, Michael (1975), Fage, J. D. (ed.), The Fatimid revolution and its aftermath in North Africa, The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 589–636, ISBN 0-521-21592-7

- Hrbek, Ivan (1977), Oliver, R. (ed.), The Fatimids, The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–27, ISBN 0-521-21592-7

- Sanders, Paula A. (1994), Ritual, politics, and the city in Fatimid Cairo, SUNY series in medieval Middle East history, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1781-6

- Walker, Paul E. (1998), Daly, M. W.; Petry, Carl F. (eds.), The Ismaili Dawa and the Fatimid caliphate, The Cambridge history of Egypt, I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 120–150, ISBN 0521068851

- Sanders, Paula A. (1998), Daly, M. W.; Petry, Carl F. (eds.), The Fatimid state, 969-1171, The Cambridge history of Egypt, I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–174, ISBN 0521068851

- Walker, Paul E. (2002), Exploring an Islamic empire: Fatimid history and its sources, Ismaili heritage series, 7, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-692-1

- Daftary, Farhad (2007), The Ismailıis: their history and doctrines (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61636-0

- Brett, Michael (2001), The rise of the Fatimids: the world of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the fourth century of the Hijra, tenth century CE, The Medieval Mediterranean, 30, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-11741-5

- Bresc, Henri; Guichard, Pierre (1997), Fossier, Robert (ed.), Explosions within Islam, 850-1200, The Cambridge illustrated history of the Middle Ages, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 146–202, ISBN 0-521-26645-9

- Meri, Josef W. (2005), Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-96690-6

External links

- Fatimid Rock Crystal Ewers, Most Valuable Objects in Islamic Art

- Trésors fatimides du Caire, exhibition of Fatimid art at the Institut du Monde Arabe

- Bronze animal statuary (aquamaniles, incense burners, fountain fixtures. perfume dispensers): lion 1, lion 2, lion 3, cheetah, stag, hind, gazelle, ram, hare, bird, parrot

- Rock crystal ewers: Venice 1, Venice 2, Berlin

- Carved ivory frame, Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art