Fingal

Fingal (English: /ˈfɪŋɡəl/ FING-gəl; from Irish Fine Gall 'foreign tribe') is a county in Ireland. It is located in the province of Leinster and, within that, is part of the Dublin Region. Its name is derived from the medieval territory of Scandinavian foreigners (Irish: gaill) that settled in the area. Fingal County Council is the local authority for the county. In 2016 the population of the county was 296,214, making it the second-most populous county in the state.[2]

Fingal

Fine Gall | |

|---|---|

County | |

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): | |

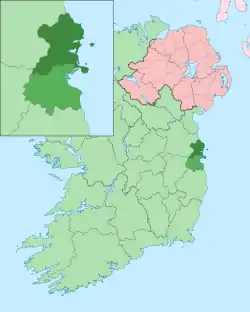

Fingal (dark green) shown within County Dublin (lighter green) and within Ireland (light green) | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Dáil Éireann | |

| EU Parliament | Dublin |

| Established | 1994 |

| County town | Swords |

| Government | |

| • Type | County Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 456 km2 (176 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 176 m (577 ft) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 296,214 |

| • Density | 650/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode | D11, D15, K32, K34, K36, K45, K56, K67 |

| Telephone area codes | 01 |

| Vehicle index mark code | D |

| Website | www |

Geography and political subdivisions

Fingal is one of three counties into which County Dublin was divided in 1994. Swords is the county town. The other large urban centre is Blanchardstown. Smaller towns include Balbriggan and Malahide. Suburban villages with extensive housing include Baldoyle, Castleknock, Howth (and Sutton), Lusk, Portmarnock, Skerries.[3] Small rural settlements exist in the northern and western parts of the county. The motto of the arms of Fingal reads Irish: Flúirse Talaimh is Mara meaning "Abundance of Land and Water". The motto reflects the strong farming and fishing ties historically associated with the area. It also features a Viking longboat, which represents the arrival of the Norse in Fingal, where they became integrated with the existing Irish. Fingal is bordered by County Meath to the north, by Kildare to the west and by Dublin city to the south. At the Strawberry Beds, the River Liffey separates the county from South Dublin.

Towns and villages

Fingal varies enormously in character, from densely populated suburban areas of the contiguous Dublin metropolitan to remote rural villages and lowly unpopulated agricultural townlands.

Fingal County Council is also responsible for the northernmost parts of Ballymun, Santry and Finglas. The part of Kilbarrack now known as Bayside, along with Sutton and Howth (the peninsula was historically distinct from the plains of Fingal), were transferred from the city of Dublin in a somewhat controversial move. Clonee, part of County Meath, has housing estates in its hinterland that merge into the estates of Ongar in western Fingal.

Baronies and Civil parishes

.png.webp)

The former county of Dublin was divided into nine baronies.[4 1] While baronies continue to be officially defined units, they are no longer used for many administrative purposes. The last boundary change of a barony in Dublin was in 1842 when the barony of Balrothery was divided into Balrothery East and Balrothery West. Their official status is illustrated by Placenames Orders made since 2003, where official Irish names of baronies are listed under "Administrative units". The boundaries of Fingal do not respect the boundaries of the baronies. As a result, only three baronies are entirely contained in the county: Balrothery East, Balrothery West, and Nethercross. Parts of three baronies are also contained in the county: Castleknock,Coolock, and Newcastle.

In the case of Castleknock, most civil parishes of the barony are under the jurisdiction of Fingal County Council. Some of the eastern parishes are under the jurisdiction of Dublin City Council. The core of the civil parish of Finglas lies within Dublin City. There are two substantial exclaves of the parish proper that are located in Fingal.

In the case of Coolock, most civil parishes of the barony are the jurisdiction of Dublin City Council. The parishes listed in the table below are located in Fingal.

| Name in Irish | Name in English | Area in Acres |

|---|---|---|

| Baile Dúill | Baldoyle.[4 2] | 450 |

| Baile Ghrífín | Balgriffin.[4 3] | 540 |

| Binn Éadair | Howth.[4 4] | 1772 |

| Cionn Sáile | Kinsaley.[4 5] | 1339 |

| Clochrán | Cloghran.[4 6] | 994 |

| Mullach Íde | Malahide.[4 7] | 606 |

| Port Mearnóg | Portmarnock.[4 8] | 1020 |

| Sord | Swords.[4 9] | 5 |

| Teampall Mhaighréide | St. Margaret's[4 10] | 1140 |

In the case of Newcastle, most of the barony is situated south of the River Liffey and so is under the jurisdiction of South Dublin County Council. Six townlands are located north of the Liffey in the civil parish of Leixlip. Listed in the table below, they are part of Fingal.

| Name in Irish | Name in English | Area in Acres |

|---|---|---|

| Coill Alain | Allenswood[4 11] | 210 |

| - | Coldblow[4 12] | 279 |

| Láithreach Con | Laraghcon[4 13] | 295 |

| - | Pass-If-You-Can[4 14] | 88 |

| Páirc San Caitríona | Saint Catherine's Park[4 15] | 195 |

| Baile an Bhaspailigh | Westmanstown[4 16] | 437 |

History

Terminology and etymology

The name "Fingal" derives from the medieval territory of Fine Gall (tribe or territory of foreigners), the Viking settlement north of Dublin.[4] The Vikings referred to the hinterland of Dublin as Dyflinarskiri.[5]

In Ireland, the usage of the word county nearly always comes before rather than after the county name; thus "County Clare" in Ireland as opposed to "Clare County" in Michigan, US. In the case of those counties created after 1994, they often drop the word county entirely, or use it after the name; internet search engines show many more uses (on Irish sites) of "Fingal" than of either "County Fingal" or "Fingal County". The local authority uses all three forms.[6]

Fingallian is an extinct language, a hybrid of Old and Middle English and Old Norse, with Gaelic influences. It was spoken by the people of Fingal until the mid-19th century.

Legal history

Not until the Norman invasion of Ireland did the settlement and its hinterland become an administrative area. In 1208 the Lordship of Fingal was granted to Walter de Lacy by King John of England.[7] The modern county of Fingal was established on 1 January 1994[8] with the division of the administrative county of Dublin under the Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1993.[9] The Act provided for the legal establishment of the following local government administrative areas:

and also recognised the local government administrative area under the jurisdiction of the extant Dublin Corporation, vesting its powers in a renamed entity – Dublin City Council. The statutory instrument giving effect to the Act provided for the abolition of Dublin County Council – the entity that previously had responsibility for Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, Fingal and South Dublin. The four entities collectively comprise the former entity known as County Dublin. The former County Dublin, which had been created as a feudal entity in the 12th century, was abolished under the Acts.

Fingal is within the remit of the Eastern and Midland Region, established in 2015, one of three such regional authorities in the state.[10]

Early Gaelic history

In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy identified Eblana (Dublin) as the capital of a people called the Eblani. In later centuries the territory north of the river Liffey was known as Mide or Midhe, i.e. "the Kingdom of Meath" (that to the south was known as Coigh Cuolan or Cualan). The west of this area was known as Teffia, and the east as Bregia (Latinised from Gaelic Magh Breagh, "the great plain of Meath"). Bregia comprised five Gaelic triocha-cheds (equivalent to cantreds) or the later baronies, and was ruled by the king at Tara.[11] These princes, and various Gaelic chieftains, held sway over the area until the coming of the Vikings in the 8th century.

Vikings and Hiberno-Norse

By 841 AD a Scandinavian settlement had been established at Dublin; this was abandoned in 902, re-established in 917, and developed thereafter. It was so established by the 11th century that it was regarded even amongst the surrounding native Gaelic population as a minor kingdom[12] ruled by Hiberno-Norse kings. The Norse Kingdom of Dublin stretched, at its greatest, from Drogheda to Arklow, and while mostly a thin strip of coastal land, from the Irish Sea westwards as far as Leixlip in the central part.

After the Battle of Clontarf, when High King Brian Boru curtailed the power of the Vikings in Ireland, the Norse-Irish Kingdom of Dublin continued, with its own bishop, part of the Westminster hierarchy rather than the Irish, though it gradually came under the influence of the Kings of Leinster. Diarmait Mac Murchada established himself there before his expulsion by the High King in 1166, a series of events which led to the area being invaded in the late 12th century, by the Cambro-Normans. This was to form part of the heartland of the area known as The Pale during the successive periods of rule by Anglo-Norman and the later kings of England.

Early Anglo-Norman grants

With the arrival of the Anglo/Cambro-Normans in 1169,[13] the territory of the old Gaelic Kingdom of Meath was promised in around 1172 to Hugh de Lacy by King Henry II of England. At that time, Meath extended to most of the current county of Fingal (including as far as Clontarf, Santry and the barony of Castleknock), County Westmeath and part of County Kildare. Fingal was therefore implicitly included in the grant of "Meath" either as part of Meath proper or under the additional element of that grant[14][15] "and for increase to the gift, all fees which he has or shall acquire about Dublin". This element of the grant related to his role as Bailiff[16] and was copied into the Gormanston Register.[17]

Strongbow was probably also assigned some fees within the royal demesne of Dublin,[18] as in the case of Hugh de Lacy's custodianship of Dublin, in payment of his services. This appears evidenced by several grants which he made in his own name within the city to St. Mary's Abbey, and his foundation of a hospital of St. John of Jerusalem at Kilmainham. Therefore, both Strongbow and Hugh de Lacy exercised lordships within the royal demesne of Dublin.

In addition to Dublin city, the royal demesne itself also consisted of the royal manors of Crumlin, Esker, Newcastle, and Saggart, in the south-west of the county, and the royal demesnes of O Thee (O'Teig), O Brun (O'Broin), and O Kelly (O'Ceallaigh) in the south-east of the county, which were rented from the Crown by Irish-speaking tenants.[19] Over half of the land in the county of Dublin was granted to religious houses and priories, as well as archbishops and monasteries, and minor lay lords. In such way too, an estate was given to the Irish chieftain MacGillamocholmog, who held sway over the territory of Cualann (Wicklow) when the Anglo-Normans arrived.[20]

De Lacy parcelled out most of this land to his vassals, who were to hold these lands from him, as he had held the Lordship of Meath from King Henry, by military tenure. D'Alton also provides a reference to the enumeration of these grants given in Hibernica, by Harris (pp. 42–43). Hugh de Lacy was appointed Viceroy in 1178, and again in 1181 after a brief period of royal disfavour.

By virtue of his grant of Meath, Hugh de Lacy was appointed a Palatine Count in that territory[21] and divided it amongst his various vassals who were commonly called "De Lacy's Barons". These were: Hugh[22] Tyrell, Baron of Castleknock; Jocelyn de Angulo, Baron of Navan and Ardbraccan; De Misset, Baron of Lune; Adam de Feypo, Baron Skryne;[23] Fitz-Thomas, Baron of Kells; Hussey, Baron of Galtrim; Richard de Fleming, Baron Slane; Adam Dullard or Dollard, of Dullenvarty; Gilbert de Nugent, Baron Delvin and later Earl of Westmeath;Risteárd de Tiúit, Baron of Moyashell; Robert de Lacy's descendants, Barons of Rathwire; De Constantine, Baron of Kilbixey[24] Petit, Baron of Mullingar; Meyler FitzHenry of Maghernan, Rathkenin, and Ardnocker. As Burke points out, to some of these there descended the De Genevilles, Lords of Meath; Mortimer, Earl of March (and later Lord of Trim, from De Geneville); the Plunkets, of Danish descent, Baron of Dunsany and of Killeen, and later Earl of Louth and Earl of Fingall (by letters patent); the Prestons, Viscounts Gormanston and Viscount Tara, the Barnewalls, Baron Trimlestown and Viscount Barnewall; the Nettervilles, Barons of Dowth; the Bellews, Barons of Duleek; the Darcys of Platten, Barons of Navan; the Cusacks, Barons of Culmullin; the FitzEustaces, Baron Portlester. Some of these again were succeeded by the De Baths of Athcarn, the Dowdalls of Athlumny, the Cruises, the Drakes of Drake Rath, and others.[25]

John of England

In 1184, Prince John, then Lord of Ireland and Earl of Mortain[26] gave half the tithes of Fingal to the episcopal see of Dublin, which grant was confirmed in 1337 by King Edward, and in 1395 by King Richard II when in Dublin.[27]

This John was none other than the same who featured so prominently in the tales of Robin Hood during the reign of King Richard the Lionheart (Coeur de Lion) absent on the Third Crusade. In 1189, on the breaking up of Robin Hood's company, Robin Hood's great companion Little John, is said to have exhibited his feats of archery on Oxmanstown Green in Dublin, until having been detected in a robbery, he was hanged on Arbour Hill nearby.[28] Another Robin Hood-type, known as McIerlagh Gedy, is recorded as a notorious felon responsible for many thefts and incendiary acts in Meath, Leinster, and Fingal, and was taken prisoner, brought to Trim Castle and hanged.[29]

Walter de Lacy, Lord of Meath, son of Hugh,[30] gained seisin of the Lordship of Meath by charter in 1194 during Richard I's exercise of the Lordship of Ireland, having previously been a minor when his father Hugh de Lacy died in 1186.[31] Walter succeeded to all Hugh's lordships, including of Fingal, which by grant of King John in 1208 was subsequently confirmed in perpetuity under the same terms as the palatine Lordship of Meath, and no longer limited by the original conditions linked to service as bailiff of Dublin.

Prescriptive Barony, 1208

The first known administrative provision related to the original name was a palatine grant of the Paramount Lordship of Fingal, confirmed by letters patent from King John.[32] This feudal barony or Prescriptive barony was granted to Walter de Lacy and his heirs in perpetuity in 1208. The grant was based on Hugh de Lacy, Walter's father, having held the same on a basis of grand serjeanty for his services as bailiff to the King.[33] The grant describes the scope of administrative responsibility, and the limits of powers delegated. The gist of the grant is recounted as follows:

Grant and confirmation to Walter de Lascy, on his petition, of his land of Meath; to hold of the King in fee by the service of 50 knights; and of his fees of Fingal, in the vale of Dublin; to hold in fee by the service of 7 knights; saving to the King pleas of the Crown, appeals of the peace, & c., and crociae, and the dignities thereto belonging; the King's writs to run throughout Walter's land. Further grant to Walter of the custody of his fees, although the lords thereof hold elsewhere in capite; saving to the King the marriages of the heirs of those fees.[34]

Other derivative or related grants and titles

As mentioned above, by the time King John granted Finegal as part of his inheritance to Walter, Walter's father Hugh had already sub-infeudated parts thereof to his vassals (e.g. the Castleknock barony, granted by Hugh de Lacy to Hugh Tyrell, etc.). Therefore, Finegal was already a superior lordship (or paramount barony) when originally granted, consisting of lesser baronies (and their several manors), even though some of these may have been granted by Hugh in his capacities as Bailiff or as Viceroy, and later confirmed as held of the Crown in capite, and in perpetuity. The lordship of Fingal was, therefore, a paramount superiority over several sub-infeudated smaller baronies (such as Castleknock, Santry, Balrothery),[35] and thus eventually accrued vicecomital attributes.

In addition, several other baronies existed as feudal holdings or were created within the geographical territory of Fingal (such as Finglas;[36] Swerdes Swords;[37] Santry, Feltrim[38]), and in other parts of Dublin: Howth[39] and Senkylle (Shankill in southern Dublin).[37]

A later, related, development was the granting of the first viscountcy in Ireland in 1478 to a Preston, Lord Gormanston, the Premier Viscount of Ireland, who at the time was a major landowner in the Fingal area, and a direct descendant of Walter de Lacy.[40] That viscountcy was called after Gormanston as the latter was the principal seat and Manor of the Prestons at the time, having been acquired upon their relinquishment of occupancy of the Manor of Fyngallestoun.[41] The Viscounts Gormanston continued to retain the Lordship of the latter under reversion.,[42] and the prescriptive barony of Fingal was also retained by the Viscount Gormanston as an incorporeal hereditament in gross, until passed to the late Patrick Denis O'Donnell.[43]

Medieval taxation, and the Pale

Geographically, Fingal became a core area of the Pale, and that part of Ireland most intensively settled by the Normans and in due course the English. Records during the period 1285–92, of rolls of receipts for taxes to the King indicate Fingal as a distinct area, listed along with the baronies or lordships of Duleek, Kells, and Loxuedy, as well as Valley (Liffey), and sometimes under, sometimes separate from Dublin.[44] Later records of rolls of receipts e.g. "granted to the King in Ireland of the term of Trinity a.r.21 (1293)" for the period 1293–1301[45] also include references to Fingal listed as a lordship, again along with the baronies of Duleek and Kells, and Dublin City, and Valley, all listed under Dublin County. Several other references also exist in the chancery records of the 14th century.[46]

Abolition of feudal system

The feudal system was finally completely abolished in the Republic of Ireland under the Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act (No. 27 of 2009) passed by the Oireachtas on 21 July 2009.[47] The Act accordingly abolished feudal tenure, but preserved estates in land, including customary rights and incorporeal hereditaments.

Earldom of Fingall

A peerage title as Earl of Fingall was created in 1628, by King Charles I of England, and granted to Luke Plunkett, 1st Earl of Fingall, Baron Killeen, whose first wife, Elizabeth Plunkett née FitzGerald, thus became Lady Killeen[48][49] The Plunketts also intermarried with the Prestons, Viscounts Gormanston. The Fingall Estate Papers, acquired by the Fingal County Archives, do not however relate to any properties in Fingal, but rather to lands in Meath. That Fingall title became extinct upon the death of the 12th and last Earl in 1984, along with a peerage barony of the same name, not to be confused with the titular prescriptive barony of Fingal previously mentioned.

County Dublin

In the 1208 grant, the bulk of Fingal, considered to be "in the vale of Dublin", was part of the County Dublin, when the latter was established as one of the first twelve counties created by King John during his visit to Ireland in 1210.[50] Its history forms part of that of Co. Dublin for the following eight centuries.

The part of Fingal within County Dublin was in later centuries subdivided into the following administrative baronies: Balrothery West, Balrothery East, Nethercross, Castleknock and Coolock.

In 1985, County Dublin was divided into three "electoral counties", with "Dublin–Fingal" as the northern one.[51] In 1994, the administrative county of Dublin was abolished, and three new administrative counties similar to the electoral counties replaced it, with "Fingal" in place of "Dublin–Fingal".[52] It encompasses that part of the area anciently known as Fingal which lay within the former County of Dublin, excluding the areas north of the Tolka but within city boundaries. With the enactment of the Local Government Act 2001, Fingal is determined and listed as a county.[53]

Local government

Fingal County Council is the local authority for the county. It was established at the same time that Dublin County Council and the Corporation of Dún Laoghaire were abolished[54] in 1994, by an Act of the Oireachtas, the Local Government (Dublin) Act 1993. It is one of four councils in the Dublin Region. The County Hall is in Swords, with another major office in Blanchardstown. The county administration is headed by a County Manager, leading a team of functional heads and directors of services.[55] The county council is governed by the Local Government Act 2001. The council has 24 elected members who are elected are by single transferable vote in elections held every 5 years.

For elections to Dáil Éireann, the county is divided into Dublin North and Dublin West, with Malahide and Howth situated in the constituency of Dublin North-East and small parts of Mulhuddart being located in Dublin North-West.

Economy

Fingal is Ireland's primary horticultural region, producing 50% of the national vegetable output and 75% of all glasshouse crops grown in the country. However, the areas of production are coming under severe pressure from other development and the rural towns are increasingly becoming dormitories for the city. Howth harbour is the biggest fishing harbour on the east coast, and the fifth largest in the country.[56]

Dublin Airport is located within the county,[57] along with the headquarters of Aer Lingus and Ryanair.[58][59] The Dublin Airport Authority has its head office on the grounds of the airport.[60] In addition Swords has the headquarters of ASL Airlines,[61][62] CityJet,[63] and Ingersoll Rand.[64]

In 2006 Fingal County Council was lauded by prominent Irish construction industry figures, politicians and EU Energy Commissioner Andris Piebalgs for becoming the first local authority in Ireland to introduce mandatory sustainable building requirements.[65][66] The policy, which relates to all construction in 8 parts of the county—including roughly 13,000 new homes—stipulates that the amount of energy and CO2 emissions associated with the heating and hot water of all buildings must be reduced by at least 60% compared to Irish Building Regulations, with at least 30% of the energy used for heating and hot water coming from renewable sources such as solar, geothermal or biomass.[67]

Demographics

| Main immigrant groups, 2016[68] | |

| Nationality | Population |

|---|---|

| 12,196 | |

| 10,615 | |

| 5,455 | |

| 3,490 | |

| 3,115 | |

| 2,751 | |

| 2,574 | |

| 1,937 | |

| 1,425 | |

| 1,102 | |

Education

The Technological University Dublin formerly known as the Institute of Technology, Blanchardstown is the largest third-level education facility in Fingal.

Sport

Fingal is home to Morton Stadium,[69] Ireland's national athletics stadium and 2003 Special Olympics venue.

Between 2007 and 2011 Morton Stadium hosted the home matches of the former soccer team Sporting Fingal FC.

The county has many GAA teams which are still organised under the County Dublin GAA since the political county changes have not affected the GAA Counties (see Gaelic Athletic Association county). However, a team representing Fingal as county has competed against GAA counties as a sub-region of the GAA county of Dublin in the Kehoe Cup, Division 2B (as of 2014) of the Allianz National Hurling League and (in the past) the Nicky Rackard Cup.[70]

References

From "Irish placenames database". logainm.ie (in English and Irish). Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Baronies of County Dublin

- Baldoyle civil parish

- Balgriffin civil parish

- Howth civil parish

- Kinsaley civil parish

- Cloghran civil parish

- Malahide civil parish

- Portmarnock civil parish

- Swords civil parish

- St. Margaret's civil parish

- "Allenswood | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Coldblow | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Laraghcon | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Pass-If-You-Can | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Saint Catherine's Park | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Westmanstown | townland". logainm.ie. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

From other sources:

- "Fingal Climate Change Adaptation Plan" (PDF). Fingal County Council.

- Census of Ireland, 2016. Central Statistics Office, "Preliminary Actual and Percentage Change in Population 2011 - 2016 by Sex, Province County or City, Census Year and Statistic".

- "County development plan – strategic context" (PDF). Fingal County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- Hickey, Raymond (2005). Dublin English: Evolution and Change. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 197. ISBN 90-272-4895-8. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- F. H. A. Allen and Kevin Whelan (editors), Dublin City and County – From Prehistory to Present, Geography Publications Dublin, 1992; p. 89 ISBN 0-906602-19-X

- Fingal County Council website, where (apart from references to the Council itself) both "Fingal County" and "County Fingal" appear, but much less frequently than "Fingal" alone.

- Hardy 1835, Guildhall Library, Manuscripts Section, Aldermanbury, London. [www.cityoflondon.gov.uk Website]

- Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1993:

Section 2: "the county", in relation to any time before the establishment day, means the administrative county of Dublin

Section 9(1) On the establishment day— ... (a) the county shall cease to exist. - Bolton, Jason, Discovering Historic Fingal:A Guide to the Study of Monuments, Historic Buildings and Landscapes, 2008, p6.

- "Eastern and Midland Regional Assembly". Eastern & Midland Regional Assembly. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- See Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, by the Four Masters (written 1632–36 by a team of Franciscan scholars, led by Br. Michael O’Clery, hereditary historian to the O'Donnell Kings and Princes of Tyrconnell, and based on records surviving from the earliest times; translated by John O’Donovan, ed., 1856, reprinted by De Burca Publishers, Dublin, 1998)

- Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship, by Marie Therese Flanagan, Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, 1989, ed. 1998, p. 9

- For an account describing the religious undercurrents of this invasion, described as a "crusade" see "When the Normans came to Ireland" by Maurice Sheehy (former Professor of Palaeography and late Latin at University College, Dublin), published by Mercier Press, 1975 & 1998.

- History of Ireland by John D'Alton, 1910 (page 258)

- Note: A royal grant creates a tenant-in-chief, who could then also make a feudal grant by sub-infeudation that would create a lordship or seigneury of the grantor, still held by him in reversion.

- The original is quoted: "et de incremento illi dono omnia feoda que prebuit vel que prebebit circa Duveliniam dum ballivus meus est ad faciendum mihi servicium apud civitatem meam Duveliniae"

- Calendar of the Gormanston Register circa 1175–1397, being an extra volume of the Royal Society of the Antiquaries of Ireland, prepared and edited by James Mills, and M. J. McEnery, University Press, Dublin, 1916. See folio 5 of the Register; transliterated on page 6 of the Calendar

- Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship, by Marie Therese Flanagan, Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, 1989, ed. 1998 (page 294)

- Dublin, City and County from Prehistory to Present, edited by F. H. A. Allen and Kevin Whelan, Geography Publications, Dublin, 1992, page 91 and elsewhere for details of ancient manors and lordships

- The Environs of Dublin, by Francis Elrington Ball, M.R.I.A, in volume I of his History of the County of Dublin, (1902)

- Vicissitudes of Families by Sir Bernard Burke, Ulster King of Arms, Longman Green Longman and Roberts, Paternoster Row, London, 1861 (pages 363-364)

- First names of grantees taken from corroborating text on page 259 of D'Alton's History of Ireland (1910)

- Skrine is Skreen, or Skryne. The ancient parish from which it stems was called Scrinium Sancti Columbae and was derived from a shrine to St. Columba (ColmCille of the Cenel Conaill, proto-O'Donnells), brought over from Britain in 875, and held in a monastery there. Adam de Feypo erected a castle there, and his family founded a friary of eremites of the order of St. Augustine

- Kilbixey lies today in County Westmeath. A Richard Costentyn also held the manor of Balrothery in Fingal in 1343 (see Close Rolls, in Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Calendarium, Tresham 1828)

- These details are given in Burke's Vicissitudes of Families, in the chapter on the O'Melaghlins, Kings of Meath.

- King Henry II had sought a crown from the papacy for John's use as King of Ireland. The crown was delivered at Christmas, 1185, but never used. After Henry's death, King Richard I of England created John Count (Earl) of Mortain in 1189.

- The History of the County of Dublin, by John D’Alton, Esq., M.R.I.A., Barrister-at-Law, Hodges and Smith, Dublin, 1838

- D’Alton, op. cit. page 517

- A tale also told in D’Alton and recorded in the Rotulus Clausus (de anno 46 Edward III, para.22, page 100) in the Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Calendarium (Tresham, 1828)

- Hugh de Lacy was killed in 1186 at Durrow, County Offaly. See Flanagan's "Irish Society, etc." op.cit., for an account of the intermediate period thereafter when his son Walter was still too young to assume his father's mantle, and when Prince John administered grants until such time as King Richard assumed the Lordship of Ireland in 1194

- Flanagan, op. cit., page 282

- John, previously Prince, Lord of Ireland and Earl of Mortain, was crowned King of England in 1199: "Rex Angliae, Dominus Hiberniae, Dux Normanniae et Aquitanniae, et Comes Andegaviae, coronatus fuit in festo ascensionis Dominicae, A.D. 1199"

- Thomas Duffus Hardy (editor), Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati, published in 1837; page 178, volume 1, part 1 (available in the Tower of London with a copy in the Guildhall Library, London, containing the original text of the Grant of Fingal by King John, 1208)

- See transliteration on page 178 (anno 9-10 Johann – AD 1208) of Vol.1, Part 1, of the Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi asservati – ab anno MCXCIX ad annum MCCXVI (Thoma Duffus Hardy, published in 1837 in the reign of King William IV)

- John D’Alton, "History of Ireland", published by the author in Dublin, 1845; Volume I, page 259

- Finglas once consisted of two parts: a western portion centred on the village of Finglas, and an eastern portion centred on Artane; see Sir William Petty's map of County Dublin

- Senkylle (p. 162) and Swerdes (p.134), as well as "Fynglas" (p.134 and 162) are mentioned as baronies in the documents relating to the administration of the Earl of Ormond as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1420–1421)

- O'Fagans were feudal Barons of Feltrim

- The St. Lawrence family were originally feudal Barons of Howth

- Charles Kidd and David Williamson (editors), "Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage 1995", published by Debrett's Peerage Limited, Macmillan, London, 1995 UK: ISBN 0-333-41776-3; ISBN 0-333-62956-6; US: ISBN 0-312-12557-7, pages 534-535

- James Mills and M. J. McEnery (editors), The Calendar of the Gormanston Register, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, University Press, Dublin, 1916. The Gormanston Register is a collection of ancient manuscripts going back to the 12th century, belonging to the Viscounts Gormanston, and now lodged in the National Library of Ireland, in Dublin

- "The Calendar of the Gormanston Register", page 2

- Charles Mosley (genealogist), Blood Royal – From the time of Alexander the Great to Queen Elizabeth II, published for Ruvigny Ltd, London, 2002 (O'Donnell listed as Baron of Fyngal, page v) ISBN 0-9524229-9-9

- See Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland, Volume 3, (1879 edition)

- Calendar, op. cit., volume 4, (1881), paras. 48, 90, 113, 160, 208, 222, 261, 282, 301, 332, 364, 390, 443, 507, 528, 586

- Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Calendarium in the National Library of Ireland (reference RR 941, li), pages/paragraphs 100/22, 136/191, 166/250

- "Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act 2009 – Tithe an Oireachtas". Oireachtas.ie. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- FitzGerald, Charles William (Marquis of Kildare and later 4th Duke of Leinster). The Earls of Kildare and their Ancestors: from 1057 to 1773, 4th edition, published by Hodges, Smith & Co., Dublin, 1864 (pp. 235–236). He made the same mistake himself, i.e. that Elizabeth was a daughter rather than a sister of Bridget O'Donnell, 1st Countess of Tyrconnell, in the second edition of 1858 (page 226), but corrected this in his fourth edition in 1864

- Mary Rose Carty, History of Killeen Castle, by published by Carty / Lynch, Dunsany, County Meath, Ireland, April 1991 ISBN 0-9517382-0-8. This includes a history of the Earls of Fingall – page 18 refers to Lucas Plunkett, the 1st Earl of Fingall, and identifies his first wife as Elizabeth but mistakenly gives her as the daughter of Rory O’Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell

- A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Volume I, by Samuel Lewis, Published by S. Lewis & Co., London, 1837 (page 522)

- Local Government (Reorganisation) Act, 1985, § 12: Establishment of Dublin Electoral Counties and S.I. No. 133/1985 — Dublin Electoral Counties Order, 1985

- Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1993 § 9: Establishment and boundaries of administrative counties and S.I. No. 401/1993 — Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1993 Establishment Day Order, 1993

- Local Government Act, 2001 Part one, schedule five, pp195.

- "Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1993, Section 9.—(1)"

:"On the establishment day— ::(a) the county shall cease to exist, ::(b) the borough shall cease to exist, ::(c) the electoral counties shall cease to exist, and ::(d) the united district of the burial board shall cease to exist." - Fingal County Council Management Team, on official website retrieved 17 December 2009

- "30506 Fingal corporate Text" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Detecting Client Screen Resolution". Maps.fingalcoco.ie. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "compreg.pdf Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine." Ryanair. Retrieved on 25 May 2009.

- "About Us Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine." Aer Lingus. Retrieved on 7 July 2010.

- "Contact Us Archived 24 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine." Dublin Airport Authority. Retrieved on 7 July 2010.

- "Contact Us Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine." ASL Aviation. Retrieved on 24 February 2011. "Contact ASL Aviation Group Limited The Plaza Swords Co. Dublin Ireland."

- "How to find us Archived 11 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine." ASL Aviation. Retrieved on 24 February 2011.

- "CityJet Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine." Air France. Retrieved on 21 June 2010. "Address: CityJet Ltd. Swords Business Campus Balheary Road Swords, Co. Dublin Ireland"

- "Contact Us Archived 2 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine." Ingersoll Rand. Retrieved on 18 January 2011. "Global Headquarters 170/175 Lakeview Drive Airside Business Park Swords, Co. Dublin Ireland."

- Fingal Commits – Local Authority adopts Radical Planning Requirements -:- Construct Ireland Archived 11 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- EU Energy Commissioner on Ireland's Energy Future -:- Construct Ireland Archived 23 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fingal Commits – Local Authority adopts Radical Planning Requirements -:- Construct Ireland". Constructireland.ie. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/define.asp?MainTable=E7050&ProductID=DB_E7&PLanguage=0&Tabstrip=&PXSId=0&SessID=7827795&FF=1&tfrequency=1

- "Morton Stadium, Dublin> View Stadium". worldstadia.com. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Dublin County Board back Fingal's motion to rejoin hurling championship". The Irish Times. 8 January 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Fingal and its Churches – A Historical Sketch, by Robert Walsh, M. A., Dublin and London, 1888.

- Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati, edited by Thomas Duffus Hardy, published in 1837. (Available in the Tower of London and in the Guildhall Library, London, it contains original text of the Grant of Fingal by King John in 1208).

- The Calendar of the Gormanston Register, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, edited by James Mills and M.J. McEnery, University Press, Dublin, 1916. The Gormanston Register is a collection of ancient manuscripts going back to the 12th century, belonging to the Viscounts Gormanston, and now lodged in the National Library of Ireland, in Dublin.

- History of Killeen Castle, by Mary Rose Carty, published by Carty / Lynch, Dunsany, County Meath, Ireland, April 1991 (ISBN 0-9517382-0-8). This includes a history of the Earls of Fingall – page 18 refers to Lucas Plunkett, the 1st Earl of Fingall, whose first wife is given as Elizabeth O'Donnell of Tyrconnell, but she was, in fact, a Fitzgerald, sister of Bridget FitzGerald

- Blood Royal – From the time of Alexander the Great to Queen Elizabeth II, by Charles Mosley (genealogist), published for Ruvigny Ltd, London, 2002 (O'Donnell listed as Baron of Fyngal, page v) ISBN 0-9524229-9-9

- History of the County of Dublin, by Francis Elrington Ball, Dublin, 1902.

- History of the County of Dublin, by John D'Alton, Hodges and Smith, Dublin, 1838.

- Dublin City and County: From Prehistory to Present, edited by F. H. A. Allen and Kevin Whelan, Geography Publications, Dublin, 1992 ISBN 0-906602-19-X.

- Seventy Years Young, Memoirs of Elizabeth, Countess of Fingall, by Elizabeth Burke Plunkett, Lady Fingall. First published by Collins of London in 1937; 1991 edition published by The Lilliput Press, Dublin 7, Ireland ISBN 0-946640-74-2. This Elizabeth was a Burke from Moycullen in County Galway, who married the 11th Earl of Fingall, and should not be confused with Elizabeth O'Donnell, 1st Countess of Fingal.

- The Scandinavian Kingdom of Dublin, by Charles Haliday, edited by John P. Prendergast, published by Alex. Thom & Co., Printers and Publishers, Dublin, 1881.

- Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage 1995, edited by Charles Kidd and David Williamson, published by Debrett's Peerage Limited, Macmillan, London, 1995 UK: ISBN 0-333-41776-3; ISBN 0-333-62956-6; US: ISBN 0-312-12557-7