Greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey

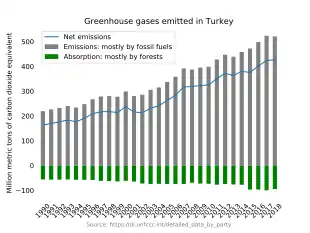

Turkey emits about 500 million tonnes of human-made greenhouse gas (GHG) every year, which is around one percent of the world's total. Greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey are mainly carbon dioxide (CO

2) from burning coal, oil and natural gas. Most coal is burnt in the nation's power stations. Oil is refined and fuels almost all Turkey's cars, trucks. and planes, Natural gas heats buildings and generates electricity. Growing forests take up some carbon dioxide, but not nearly as much as is being discharged into the air.

Far less methane (unburnt natural gas) and nitrous oxide (N

2O) is emitted, but they are more potent than carbon dioxide in the short-term. Methane leaks from some coal mines and is belched by cattle. Nitrous oxide is given off by manure and fertilised soil. Whereas carbon dioxide emissions stay in the atmosphere for centuries, methane is broken down in years and nitrous oxide in decades.

In 2019 of emissions by country Turkey was the 15th largest emitter,[2] and the main influence on emissions is the government through national policy on energy, construction, transport, and agriculture.

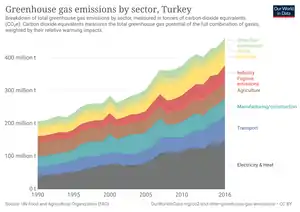

Coal, cars, cows, and construction emitted about half of Turkey's 2018 gross GHG of 520 million tons (Mt) of CO2eq.[3][lower-alpha 1] About 100 Mt was reabsorbed by land use, land-use change, and forestry, mostly by forests.[5] Turkey emits about one percent of the world's total GHG,[3][6] averaging over six tonnes per person[3] (about the global per-person average).[7] The burning of fossil fuels for electricity, heat and transport made up over 70 percent of the country's 2018 GHG; industry and agriculture were over 10 percent each,[3] and forests (including reforestation) absorbed about 20 percent. Coal (used to generate electricity, for heating and by industry) accounts for the largest part of Turkey's fossil-fuel CO

2 emissions, followed by petroleum products (used for transport) and natural gas (used for heating and electricity generation).

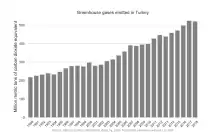

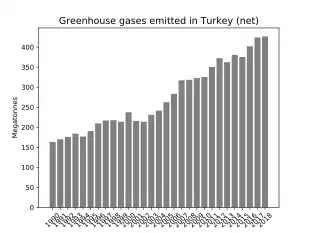

Although climate change in Turkey is forecast to impact future generations severely,[8] the independent research organization Climate Action Tracker has called the country's plans to limit emissions "critically insufficient".[9] Turkey has signed, but not ratified, global agreements on reducing GHG emissions; the country has not yet ratified the Kigali Accord to regulate hydrofluorocarbons, and is one of the few countries that have not ratified the Paris agreement on climate change. A major reason for Turkey's high rate of emissions is that coal-fired power stations in Turkey are subsidized. Emissions increased quickly during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, although Turkey increased investment in energy efficiency and its renewable resources during the 2010s and 2020s.[10] The country will probably meet the "unambitious" Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDC) it has submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[11]

Overview

The most recent available data compiled by the International Energy Agency shows Turkey is among the 20 countries which emitted the most carbon dioxide in 2018. It is ranked as the 15th largest emitter of total CO2 (0, 42 GT) and 16th largest emitter of CO2 per capita (5.21T).[12] According to the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research in 2019, 1.09% of total CO2; 5.1 tons CO2 per capita and 0.18 ton CO2 / $ 1000 was emitted.[13] Turkey emits about 500 Mt CO2eq gross each year, about 6 tons per person.[14] Almost three quarters is from the energy sector,[14] the largest source being Turkey's coal-fired power stations.[15] Despite the country being one of the largest emitters of CO2 to the atmosphere, Turkey's commitment is not in line with the objective of the Paris agreement to limit temperature rise 2°C. If all countries like Turkey refused to commit, the heating could even exceed 4°C.[16] Climate Action Tracker (CAT) predicts a reduction in emissions during the Covid-19 pandemic which will have only a limited impact. They forecast emissions will resume their course after the pandemic and reach 40% to 70% above the 2020 level by 2030.[17]

Plans and target

According to the Eleventh Development Plan (2019–2023), "Within the framework of Intended National Contribution, activities for emission control will be carried out in GHG emitting buildings, energy, industry, transportation, waste, agriculture and forestry sectors."[18] In 2015, Turkey submitted its emissions target to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), "up to 21 percent reduction in [greenhouse gas (GHG)] emissions from the Business as Usual level by 2030" and aiming to emit 929 Mt of CO2 (before subtracting CO2 absorbed by forests) in 2030.[19] However, such an increase during the 2021–2030 implementation period (see graph) would emit over 10 tonnes per person in 2030.[20] The national strategy and action plan only partially covers short-term mitigation,[21] and the OECD has recommended that climate change mitigation efforts be increased.[22] According to Climate Transparency to take a fair share to achieve 1.5C Turkey would need to reduce to 365 Mt CO2e by 2030, 226 Mt CO2e by 2050 and net zero by 2070.[23]

Comparison with EU target

Unless Turkey's energy policy is changed,[24] European Union (EU) emissions per person are forecast to fall below Turkey's during the 2020s.[25] Since the EU is Turkey's main trading partner, a comparison with targets in the European Green Deal is important to help avoid future carbon tariffs on Turkish exports such as steel[26] and cement.[27] Funding of 1 billion euros is available under the deal.[28] Turkey joining the EU Emission Trading Scheme would reportedly be more economically-beneficial for the power sector than a carbon tariff.[29]

Greenhouse gas sources

83 million people live in Turkey: annual per-person gross emissions are about the world average (over six tonnes)[7] and need to be reduced to meet the global carbon budget.[31][32] The government's Turkish Statistical Institute (Turkstat) follows Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines and uses production-based GHG emissions accounting to compile the country's emission inventory, which is submitted to the UNFCCC each April (about 15 months after the end of the reported year).[33][lower-alpha 2] As Turkey imports only slightly more CO

2 than it exports, the level of consumption-based emissions is similar to production-based emissions,[35] and was estimated by the Global Carbon Project to have been 470 Mt of CO2eq in 2017.[36][37] Turkey's cumulative CO

2emissions are estimated to be around 10 billion tonnes, which is 0.6% of the world's cumulative total.[35]

Burning fossil fuels for heat and power

According to the Turkish Energy Ministry, "Our country aims to use our energy resources efficiently, effectively and in a way that has a minimum impact on the environment within the scope of the sustainable development objectives".[38] Combustion of coal in Turkey contributed most to 2018 fossil-fuel emissions, followed by oil and natural gas.[4] That year, Turkey's energy sector[lower-alpha 3] emitted almost three-fourths of the country's GHG; industrial processes and product use (IPPU) and agriculture each emitted one-eighth.[3] The largest emitters are electricity generation, followed by transport.[39] Carbon capture and storage is extremely rare in Turkey; it is not economically viable, since the country has no carbon emission trading.[40]

Power stations

Turkey's coal-fired power stations (of which many are subsidized) are the largest source of greenhouse-gas emissions by Turkey.[41] Production of public heat and electricity emitted 149 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2018,[42] mainly through coal burning.[lower-alpha 4] Almost all coal burnt in power stations is local lignite or imported hard coal. Coal analysis of Turkish lignite compared to other lignites indicates that it is high in ash and moisture, low in energy value and high in emission intensity (i.e., Turkish lignite emits more CO2 than other countries' lignites per unit of energy when burnt).[44] Although imported hard coal has a lower emission intensity when burnt, the life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions account for transportation, and are therefore similar.[45]

With its nuclear power station not yet completed, and despite the potential for expanded renewable energy in Turkey (which, except for geothermal, emits little CO2eq), the country averages a grid emission intensity of over 460 gCO2eq/kWh (over 125 t/TJ,[46] similar to that of natural gas). A trial of reinjecting geothermal gas back into the ground is planned for 2021.[47]Coal-fired stations

Coal-fired power stations emitted 111 Mt CO2eq in 2018.[48] If operated at the targeted capacity factor, planned units at Afşin Elbistan would add over 60 million tonnes of CO

2 per year.[49] By comparison, total annual emissions are about 520 million tonnes;[50] more than one-tenth of the country's GHG emissions would be from the planned power station.[51][lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6]

Coal in Turkey is the largest source of GHG. Over a million tonnes of CO2 is emitted for every TWh of electricity generated in Turkey by coal-fired power stations.[45] When emissions from industry and building heating and methane emissions from coal mining are added to coal-fired electricity generation, about one-third of Turkey's annual emissions come from coal.[lower-alpha 7] In 2018, coal emitted over 150 Mt CO2eq.[4] Annual methane emissions from underground coal mining are estimated at two Mt CO2eq, and three Mt from open-pit mining.[57] Eren Holding (via Eren Enerji's coal-fired ZETES power stations) emits over two percent of Turkey's GHG, and İÇDAŞ emits over one percent via its Bekirli coal-fired power stations.[58]

Gas-fired stations

Gas-fired power stations emitted 37 Mt CO2eq in 2018,[59] but it was difficult for them to compete with coal due to the lack of a carbon tax.[60] The spark spread for 55-percent efficient gas-fired plants was around $7/MWh in mid-2020.[60] As of 2020, some power utilities (including eight gas-fired plants) were struggling to repay their foreign currency debts because of depreciation of the lira[61] and long-term BOTAŞ gas-purchase contracts.[60] Offtake guarantees (a subsidy received by some gas-fired plants) end in 2020.[62]

Transport fuel

Transport emitted 85 Mt of CO2eq in 2018,[63] about one tonne per person[64] and 16 percent of the nation's total. Road transport in the country dominated emissions with 79 Mt, including agricultural vehicles.[65] More than three-quarters of Turkey's road-transport emissions come from diesel fuel.[66] Average emissions of new cars in 2016 were about 120 gCO2/km;[67] although the EU has a 2021 target of 95 gCO2/km, Turkey has no target. As of 2018, Turkey had no measures to reduce the well-to-wheel impact of petrol and diesel vehicles.[68] Fuel quality and emissions standards for new cars were less strict in 2020 than those in the EU;[69] about 45 percent of cars are over 10 years old and energy-inefficient.[64]

Domestic flights[lower-alpha 8] emitted 4 Mt of CO2eq in 2018,[70] and Istanbul Airport opened the following year.[71] Turkish Airlines did not respond to the 2018 Carbon Disclosure Project questionnaire,[72] and in 2019 the airline was named as one of those with the weakest plans to reduce emissions.[73]

Fuel for heating and cooking

Residential fuel, such as natural gas, coal and wood, contributed 39 Mt CO2eq in 2018.[74] Subsidies for poor families to use coal for heating produce black carbon (a contributor to climate change)[75] and other local air pollution. Burning fuel such as coal and natural gas to heat commercial and institutional buildings emitted 14 Mt CO2eq in 2018.[76]

Industry

In 2018, Turkey's industrial sector emitted one-eighth of the country's GHG.[3] As of 2019, estimates of the effects of government policy on industrial emissions are lacking.[77] Some industrial companies reach Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) 305 emissions standard.[78]

Iron and steel

The European steel industry has complained that imports from Turkey are unfair competition because they are not subject to a carbon tax,[79] and alleges that the natural gas used to produce them is subsidized.[80] Turkish steel, primarily from minimills, averages about one tonne of CO2 per tonne produced (less than China and Ukraine in 2020).[81] However the 3 integrated steelworks Erdemir, İsdemir and Kardemir use blast furnaces and thus emit more than those using electric arc furnaces.[82] Some businesspeople are concerned that a future European Green Deal might include a carbon tariff on products such as Turkish steel,[83] but this could also provide opportunities such as competitiveness against products such as Ukrainian steel.[84]

Cement

Turkey is the fourth-largest cement producer in the world,[85] and the country's 2017 cement production emitted seven percent of its total GHG.[86] Although Turkey's construction sector contracted at the end of 2018[87] (using less cement),[88] 72.5 Mt of cement were produced in 2019; of that, 64.5 Mt were sold in the country.[89]

Agriculture and waste

Agriculture accounted for one-eighth of Turkey's 2018 GHG emissions,[3] primarily due to enteric fermentation, agricultural soils, and fertilizer management.[91] In the agricultural sector, cattle emit the most GHG.[lower-alpha 9] The amount of nitrous oxide emitted by agricultural soils is uncertain.[92]

Turks eat an average of 15 kilograms (33 lb) of red meat per person each year, and the country produced one million tonnes of beef in 2019.[90] There are about 18 million cattle in the country; over 600,000 live cattle were imported in 2019, and cattle[90] and fuel for agriculture are subsidized.[93] Sheep and goats, which are also subsidized, emit less GHG than cattle.[90] as of 2019, estimates of the effects of government policy on the agricultural and waste sectors' emissions are lacking.[77] Although sugar beets are not significant emitters, some sugar factories (such as some owned by Türkşeker[94] and Konya Seker) burn coal for the heat needed by the process of making sugar and sometimes also to generate electricity.[95] Climate-smart agriculture is being studied.[96]

The waste sector contributed 3.4 percent of Turkey's 2018 GHG emissions,[3] and landfilling is the most common waste-disposal method.[97] Organic waste sent to landfills emits methane, and the country is working to improve sustainable waste and resource management;[98] some favor composting,[99] and others argue for incineration.[97] 14% of food was lost during agricultural processing in 2016, and 23% was trashed by consumers before eating and 5% as leftovers.[100]

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

By historical responsibility between 1965 and 2016 it is estimated that Turkey would be responsible for 0.69% of required global reductions.[101] Turkey's Energy Efficiency Action Act, which came into force in 2018, commits nearly US$11 billion to efficiency and could significantly limit emissions.[102] As of 2019, however, energy efficiency policies had yet to be translated into measurable targets and measures.[24] The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is investing in energy efficiency.[103]

Energy

Emissions could be considerably reduced by switching from coal to existing gas-fired power stations,[104] because there is enough generating capacity to shut down all coal-fired power stations and still meet peak energy demand.[105] High interest rates were an obstacle to the construction of solar-power plants in 2019,[106] but a domestic solar panel factory began production in 2020.[107] After upgrading, repowering[108] and adding a small amount of pumped-storage hydroelectricity,[109] there are enough hydropower dams in Turkey to provide dispatchable generation to balance variable renewable energy, even if future rainfall lessens due to climate change.[110] Wind and solar power could expand to avoid carbon lock-in if Turkey's energy policy changed to remove its US$1.6 billion annual fossil-fuel subsidies.[110] Experimentation with hydrogen distribution is planned for 2021;[111] moving towards a hydrogen economy[112] (for heating, for example) could reduce dependence on imported natural gas. In rural areas without a piped gas supply, heat pumps may be an alternative. Geothermal-electric capacity totalled 1.6 gigawatts in 2020 (with potential for expansion), but it is unclear how much Turkish geothermal power is low-carbon.[113][114] National and international investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency are being made; for example, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development is supporting the installation of smart meters.[115]

Buildings

Turkey was a co-leader of the group discussing zero-carbon buildings at the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, and the city of Eskişehir pledged to convert all existing buildings to zero emissions by 2050.[116][117][118] However, Turkish building codes do not take into account climatic differences across the country. The 2005 Environment Act, Energy Efficiency Regulation, and green building certificates are often not properly implemented. Academics at Sabancı University have suggested adopting the EU standard to increase the proportion of passive houses (2018/844/EU, amending the directive on the energy performance of buildings).[119] Building codes will be changed to mandate charging points in new shopping malls and parking lots.[120] Geothermal heating installed capacity totals 3.5 GW thermal (GWt) in 2020 (with the potential for 60 GWt), but it is unclear how much is low-carbon.[113]

The largest reduction in emissions from cement production could be made by reducing its clinker content[121] from the current 87 percent – for example, by making LC3 cement (which is only half clinker). The second-largest reduction could be made by switching half the fuel from hard coal and petcoke to a mixture of rubber from waste tires, refuse-derived fuel and biomass.[122] Although the country has enough of these materials, most kilns use coal, petroleum coke or lignite as their primary energy source.[123] More cross-laminated timber could be used for building, instead of concrete.[124]

Further decarbonization of cement production would depend heavily on carbon capture and storage (CCS).[125] Despite Turkey's earthquake risk, CCS may be technically feasible in a salt dome near Lake Tuz[126] or in Diyarbakır Province.[127] CCS is not financially viable, however, because Turkey has no carbon pricing.

Transport

The energy intensity of transport is much higher than the other main energy consuming sectors of the economy (such as industry, agriculture, residential and commercial),[128] and in the 2010s the growing preference for internal combustion engine (ICE) sport utility vehicles (SUVs) hindered transport emission intensity reduction.[129] Although Turkey has several manufacturers of electric buses[130] and many are exported,[131] fewer than 100 were in use in the country in 2018;[132] according to a 2020 forecast, they may not saturate the local bus market until the 2040s.[133] Ebikes are manufactured, but cities could be improved to make local bicycle trips safer.[134][135] Although Turkey's ferries (unlike other countries') are still fossil-fuelled,[136] the world's first all-electric tugboat began work in Istanbul's harbor in 2020,[137] electric lorries are manufactured,[138] and an electric excavator is planned for 2022.[139] In 2020 there were 25 million vehicles on the roads,[140] and the Energy Ministry anticipated that by 2030 over 1 million would be electric.[141]

Cars

Hybrid cars are manufactured locally,[142] and Turkey's automotive industry plans to make an electric car in 2022[143] which will receive tax discounts and incentives.[144] Creation of a domestic electric vehicle market by TOGG is expected to reduce GHG emissions and costs[145] (charging being less expensive than fuelling), create jobs,[146] and reduce oil imports.[147] The introduction of smart charging is important.[148] The legality of ridesharing companies is unclear,[149][150] and taxis could be better integrated with public transport.[151] In 2019, Turkey had about 1,300 electric cars and two public charging stations per car.[152] In the first half of 2020, about 200 electric cars and about 8,000 hybrids were sold out of the country's total of 341,000 cars.[153] As of 2020, there were no low-emission zones in any Turkish cities, although enabling regulations had been introduced the previous year.[154] Although the special consumption tax(Turkish) — a sales tax on luxuries, such as private cars — and the annual motor-vehicle tax is lower for electric cars than for fossil-fuel cars, suppliers of car batteries must pay a recycling fee.[155] In 2019, 0.1% of cars sold in Turkey were hybrid or electric.[156] Partially due to high import tariffs, few foreign electric cars are sold.[157]

Carbon sinks

Turkey's 23 million hectares of forest[158] are its main carbon sink, and offset almost 20 percent of the country's emissions in 2018.[5] Reforestation and changes in land use may alter this, however,[159] and warmer and drier air in the south and west may make it difficult to sustain the present forest cover.[160] NGOs such as TEMA are encouraging reforestation, and the government said in 2015 that by 2050 "forests are envisioned to stretch across over four-fifths of the country's territory".[161] According to Ege University associate professor Serdar Gökhan Senol, however, the government may be too focused on economics and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry replants when it should wait for regrowth instead.[162]

Three-quarters of the land is deficient in soil organic matter.[163] Turkey was developing a national soil-carbon database in 2019;[164][165] this is important because carbon emissions from soil are directly related to climate change, but vary according to soil interaction.[166]

Voluntary offsets

Over 400, about 9%, of the world's voluntary carbon offset projects are in Turkey,[167] mostly wind, hydro, and landfill methane projects.[168] The main standards are the Gold Standard and the Verified Carbon Standard.[168]

Economics

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, growth of the Turkish economy and population was linked to increased emissions from electricity generation,[169] industry and construction.[170] According to the OECD fossil fuel subsidies in 2019 totalled over 25 billion lira.[171] In 2018, the government forecast that GHG emissions were expected to increase in parallel with GDP growth over the next decade.[172] When economic growth resumes after Turkey's late 2010s and COVID-19 recessions, it will be possible to expand the country's renewable-energy potential and invest in energy efficiency with a sustainable energy policy (decoupling economic growth and GHG emissions.[173] There were no explicit green measures in the 2020 package designed to recover from the country's COVID-19 recession; the VAT rate for domestic aviation was cut, and oil and gas were discounted.[174]

Fossil fuel subsidies

According to a 2020 report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development: "Turkey also lacks transparency and continues to provide support for coal production and fossil fuel use, predominantly by foregoing tax revenue and providing SOE investment."[175] According to the OECD, in 2019 petcoke's exemption from special consumption tax was a subsidy of 6.7 billion lira, the largest of Turkey's fossil fuel subsidies that year.[176] Petcoke is used in cement production.[177]

Cost-benefits of carbon pricing and ratifying the Paris Agreement

Turkey's carbon emissions are costly, even without carbon tariffs from other countries.[178] The long-term impact of climate change on any economy is highly uncertain and very difficult to estimate.[179] The short-term benefits of climate-change mitigation have been estimated at over US$50 per tonne of CO2 abated for health alone for middle-income countries generally,[180][181] and $764 million for Turkey.[182] Academics have estimated that if Turkey and other countries invested in accordance with the Paris Agreement, Turkey would break even around 2060.[183]

Boğaziçi University have developed a decision-support tool and integrated assessment model for Turkey's energy and environmental policy.[184] A study estimated that by creating a national emissions-trading market at a $50-per-tonne carbon price, Turkey's INDC commitment could be met at a cost of 0.8 percent of GDP by 2030. The study did not estimate how much the benefits would offset the cost, or the cost of not having a market.[185] In 2020, a voluntary market existed.[186] A revenue-neutral carbon tax might be best for the Turkish economy;[187] without a carbon tax or emissions trading, the country could be vulnerable to carbon tariffs imposed by the EU,[188][189] the UK or other export partners.[190] Turkey received the most EU climate-change financing by far in 2018;[191] the EBRD is investing in,[192] and have offered to support, an equitable transition from coal.[193]

In 2015, less than half of Turkey's carbon emissions from energy use were priced.[194] Taxes meet the social cost of road-transport carbon (not, however, the social cost of the country's air pollution), but all other sectors have a large gap between the actual tax (€6 per tonne of CO2 in 2018) and the tax with this negative externality; the actual cost of most GHG emissions is not borne by the emitters, violating the polluter pays principle.[195][193] Annual fossil fuel import cost savings of approximately $17 billion by meeting Paris Agreement goals have been estimated.[196]

GHG emissions and income inequality

As in other countries richer people emit more CO

2 on average as they tend to fly more, own more property and buy gasoline fuelled SUVs. However 2019 studies disagree on whether Turkey's high income inequality causes higher CO

2 emissions.[197][198]

Politics

Article 56 of the Turkish Constitution states, "Everyone has the right to live in a healthy and balanced environment. It is the duty of the State and citizens to improve the natural environment, to protect the environmental health and to prevent environmental pollution."[199] According to the Eleventh Development Plan (2019–2023):

It is seen that climate change accelerating due to high greenhouse gas emissions causes natural disasters and poses a serious threat to humanity." and "International climate change negotiations will be conducted within the framework of the Intended National Contribution with the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, and within the scope of national conditions, climate change will be tackled in sectors causing greenhouse gas emissions and the resilience of the economy and society to climate risks will be increased by capacity building for adaptation to climate change."[18]

The Climate Change and Air Management Coordination Board is responsible for coordinating government departments, and includes three business organizations.[200] Policy for a just transition from carbon-intensive assets, such as coal, is lacking[201] and there have been no public debates As of 2020.[23] Ratification[202] of the Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol, reducing hydrofluorocarbon emissions, [203] was under consideration by Parliament in 2019[204] and awaiting presidential approval.[205] As of 2020 it had not been ratified,[206] but there are some restrictions[207] and revision of the 2018 regulation is being considered.[204] As of 2021 the chief climate change envoy is Mehmet Emin Birpınar (in Turkish), a Deputy Minister of Environment.[208]

According to Ümit Şahin, who teaches climate change at Sabancı University, Turkey sees industrialized Western countries as solely responsible.[209] Limiting their actions on climate change, Turkey and other countries cited the 2020/21 United States withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.[210] For the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit on achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, Turkey co-led the coalition on the decarbonization of land transport.[211]

It has been suggested that limiting emissions through directives to the state-owned gas and electricity companies would be less effective than a carbon price (or tax), but would be more politically acceptable.[212] According to former economy minister Kemal Derviş, many people will benefit from the green transition but the losses will be concentrated on specific groups, making them more visible and politically disruptive.[213] Turkish citizens taking individual and political action on climate change on the streets[214] and online[215] include children demanding action[216] and petitioning the UN.[217]

Energy Minister Fatih Dönmez favors coal,[218] but Environment Minister Murat Kurum is planning for adaptation[219] and said in 2020 that global cooperation is key to tackling climate change.[220] Proposed and under-construction coal power is primarily financed by governments. The China-funded Emba Hunutlu power station is being built; the Turkey Wealth Fund-proposed Afşin-Elbistan C may not be constructed,[221] despite a government guarantee to purchase electricity from lignite-fired power stations until 2024 at an inflation-linked price.[222][223] Turkey's climate-change policy includes an increase in the economic life of coal reserves.[224] As of 2019, the government aimed to keep the share of coal in the energy portfolio at around the same level in the medium and long term.[225] The national development bank, the Industrial Development Bank of Turkey, says that it has implemented a sustainable business model and sustainability-themed investments have a 74-percent share of the bank's loan portfolio.[226] Turkey's Green Party is calling for an end to coal burning[2] and the phasing out of all fossil-fuel use by 2050.[227]

Paris Agreement and transboundary environmental impact treaties not ratified

According to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, climate change is one of the world's biggest problems.[228] At the G20 summit in 2020 the presidency stated: "Due to unfair status of Turkey in the current climate architecture, Turkey has not ratified the Paris Agreement yet." and "As a developing country, with a negligible historical responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions (less than 1%), Turkey looks forward to finding a fair, reasonable and wholly satisfactory solution to this issue at the earliest possible time, preferably during COP26 ... ". [229] Like neighboring Iran and Iraq, Turkey is one of the few countries which have not ratified the Paris Agreement and has refused to ratify until it receives more international loans for emission reduction and renewable-energy investments.[230][231] The EU is urging Turkey to ratify the agreement.[232] Turkey is not party to the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (Espoo Convention).[233]

Media

Electricity generated from lignite is often described by politicians and the media as generated from "local resources" and added to the renewables percentage; Daily Sabah reported that "Turkey's electricity production from local and renewable resources stood at 62 percent" in 2019.[234] Coal is described as "black diamonds" by the Anadolu Agency,[235] and natural gas as "blue gold" by TRT World.

Children's-rights petition and lawsuit

Environmental activist Greta Thunberg and 15 other children filed a petition in 2019 protesting lack of action on the climate crisis by Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, and Turkey[236][237] saying that, amongst other dangers, more deadly heat waves would affect them and other children in future.[238] The petition challenged the five countries under the Convention on the Rights of the Child:[239] "Comparable emissions to Turkey’s rate of emissions would lead to more than 4°C of warming."[240] If the petition is successful, the countries will be asked to respond; however, any suggestions are not legally binding.[241][242] In 2020, Turkey and 32 other countries were sued at the European Court of Human Rights by a group of Portuguese children.[243]

Local action

Antalya, Bornova, Bursa, Çankaya, Eskişehir Tepebaşı, Gaziantep, İzmir, Kadikoy, Maltepe, Nilüfer and Seferihisar have Sustainable Energy (and Climate) plans.[244]

Perspectives

According to journalist Pelin Cengiz, mainstream Turkish media tends to view new coal-fired power stations as increasing employment rather than causing climate change; nearly all media owners have financial interests in fossil fuels.[245] Şahin and Türkkan wrote that the media covers climate change only during extreme weather events, with insufficient expert opinions or civil-society perspectives.[246] Some construction companies have been accused of greenwashing, advertising their buildings as environmentally friendly without obtaining any green building certificates.[247]

In a 2019 E3G poll of six Belt and Road Initiative countries (including Turkey), solar was the most popular energy source and coal the least popular.[248] Twenty-four Turkish cities committed to the Paris Agreement targets that year,[249] and the United Nations Development Programme partnered with the Turkish Basketball Federation in 2020 to raise public awareness of the fight against climate change.[250] A 2020 study found that the level of public support for a potential carbon tax does not depend on whether the proceeds are used for mitigation and adaptation.[251]

Trends, research and data access

From the 1960s to the 2010s long term CO2 emissions tended to rise with income and economic growth, supporting the Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis.[252] Energy research is conducted at Sabancı University's Shura Energy Transition Center, who intend to research decarbonization pathways.[253] The UNFCCC has requested more-detailed emissions projections in Turkey's annual reports to generate Shared Socioeconomic Pathways; integrated assessment models developed by Işık University and Bosphorus University[254] are used for non-energy emissions.[255] Emissions from industry have been modelled by the Energy Ministry and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey using TIMES-MACRO.[255]

Close to 1000 entities,[168] including power plants over 20 MW and industry sectors (coke production, metals, cement, glass, ceramic products, insulation materials, paper and pulp, and chemicals over specified threshold sizes/production levels),[256] send measurements of their GHG emissions to the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization.[257] The data for a calendar year must be reported by April of the following year.[168] Unlike the public sharing of data in the European Union Emission Trading Scheme, as of 2018, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) data in Turkey was not public.[258] However some companies report their greenhouse gas emissions voluntarily: analysis of data collected by the Carbon Disclosure Project shows that they prefer specialist providers rather than audit firms and tend to have their disclosure assured to ISO14064-3 standard.[259] After 2009 the correlation between economic growth and GHG emissions weakened, with slower increase in emissions than previously per unit GDP increase.[128] Quantitative estimates of the impact of individual government policies on GHG emissions have not been made or are not publicly available;[225] neither are projections of long-term (to 2050) policy impacts.[260] Up-to-date GDP and population-growth forecasts have not been incorporated into models, and assumptions such as future energy intensity, energy demand and electricity consumption are unknown;[261] whether sensitivity analysis of GHG scenarios has been conducted is also unknown.[261] Turkey has told the UNFCCC that many details needed to understand GHG past trends and future projections "could not be provided for confidentiality reasons."[262] Although a number of issues raised in inventory reviews have been resolved, dozens more have been outstanding for over three years.[263] It is hoped that a tool similar to the South East Europe 2050 Carbon Calculator will be built for Turkey.[264] Space-based measurements of carbon dioxide are expected allow public monitoring of the megacity of Istanbul and high emitting power plants in the early-2020s.[265][266]

Notes

- Coal totals (the pie chart shows coal used for electricity), 150 Mt of CO2.[4] Figures are from Turkstat tables. Bovine enteric fermentation 1,034 kt CH4, manure management 143 kt CH4 and 6.08 kt N2O, total 42 Mt CO2eq. Construction (cement only) 37 Mt CO2. Road transport (cars not split out but likely more than half) 77 Mt CO2.

- Since "national communications" are required every four years, the fifth biennial report and eighth national communication may be combined as one document (as was the case previously).[34]

- Under IPCC guidelines, the energy sector includes fuel for transport.

- The 2018 carbon content (t/TJ), oxidation factor and CO2 emission intensity (t/TJ NCV), respectively, of the main fossil fuels burnt in Turkish power stations were:[43]

- lignite: 31, 0.973, 108

- bituminous coal: 26, 0.975, 94

- natural gas: 15, 1, 56

- 62 megatonnes would be emitted annually[49] if run at the targeted capacity factor, whereas Turkey's current annual emissions are 521 megatonnes.[50] By simple arithmetic, 62 megatonnes is more than 10% of 521+62 megatonnes.

- On average, somewhat over a million tonnes of CO2 was emitted for every TWh of electricity generated in Turkey by coal-fired power stations in 2010.[45] This power station aims to generate just over 12.5 TWh (gross) per year.[52] The calculation in the EIA assumes an emission factor of 94.6 tCO2/TJ[49] (three times the average of 31 for Turkish lignite),[53] but it is unclear whether this is the only reason the CO2 emissions per kWh are predicted to be high compared to the 2010 average. Since 2020, more stringent filtering of local air pollutants from the smokestack has been compulsory.[54] Although the average is about 2,800,[55] the net calorific value of Turkish lignite varies from 1,000 to 6,000 kcal/kg.[56]

- 29 percent of the 521 Mt gross emissions in 2018, or 35 percent of the 426 Mt net emissions

- Emissions from international trips are not included in a country's emissions total, but fuel sales for international aviation can be found in Common Reporting Format category 1.A.3.a.1A. Turkey has joined the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation.

- The following figures for cattle are from Turkstat tables: enteric fermentation 1034 kt CH4, manure management 143 kt CH4 and 6.08 kt N2O, totals 42 Mt CO2eq

References

- Gümüşel & Gündüzyeli (2019), p. 8.

- "With climate absent from Ankara's agenda, Turkey's Greens sense an opening". POLITICO. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- "Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions fall for second year in a row". Daily Sabah. 31 March 2020.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 57.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 303.

- "Türkiye'de sera gazı emisyonu azaldı" [Greenhouse gas emissions fell in Turkey]. www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "EDGAR – Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries, 2019 report – European Commission". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Fourth biennial report (2019), p. 7.

- "Turkey". Climate Action Tracker. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Firms from China, US, Turkey to build pumped-storage hydropower plant in Isparta". Daily Sabah. Anadolu Agency. 10 April 2020.

- "Brown to Green: the G20 Transition to a Low-carbon Economy" (PDF). Climate Transparency. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Each country's share of CO2 emission". Union of Concerned Scientists. Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "JRC Data Catalogue - European Commission". data.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Statistics on Environment, 2016". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- CO2 emissions from fuel combustion: Highlights (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2017. p. 97.

- Timperley, Jocelyn. "Carbon Brief Profile: Turkey". Carbon Brief. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Climate Action Tracker, Turkey. "Turkey". Climate Action Tracker. Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Eleventh Development Plan (2019–2023) (PDF) (Report). Presidency of Strategy and Budget. 2020.

- INDC (2015).

- UNEP (2019), p. 11.

- European Commission (2020), p. 101.

- OECD (2019), p. 38.

- Climate Transparency (2020).

- OECD (2019), p. 19.

- UNEP (2019).

- "EU mills push for tariffs on Turkish flats". Argusmedia. 9 October 2019.

- "E.U. carbon tariffs resurface as trade talks loom". www.eenews.net.

- "EU's Green Deal to transform Turkish exports". Anadolu Agency. 27 October 2020.

- Mezősi, András; Szabó, László; Pató, Zsuzsanna (18 August 2020). "Extended ETS outperforms carbon border adjustment in the power sector". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. iv.

- "Carbon budgets: Where are we now?". Carbon Tracker Initiative. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Children today must emit eight times less CO2 than their grandparents". Energy Post. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Reporting requirements | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Preparation of NCs and BRs | UNFCCC". UNFCCC. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (11 June 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- Friedlingstein, Pierre; Jones, Matthew W.; O'Sullivan, Michael; Andrew, Robbie M.; Hauck, Judith; Peters, Glen P. (4 December 2019). "Global Carbon Budget 2019". Earth System Science Data. 11 (4): 1783–1838. Bibcode:2019ESSD...11.1783F. doi:10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019.

- Peters, Glen P.; Minx, Jan C.; Weber, Christopher L.; Edenhofer, Ottmar (24 May 2011). "Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (21): 8903–8908. doi:10.1073/pnas.1006388108. PMC 3102371. PMID 21518879.

- "Climate Change and International Negotiation". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey).

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 43.

- Esmaeili, Danial (June 2018). Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage in the Context of Turkish Energy Market (PDF). Sabancı University. p. 15.

Having an emissions trading market is critical for a successful implementation of the carbon capturing technology in Turkey.

- "Six coal-fired plants continue to emit thick smoke after end of suspension". bianet. 2 July 2020.

- Turkstat tables (2020), table 1s1 cell B10.

- Turkstat report (2020), pp. 50 & 51, table 3.5, 3.6, 3.7.

- "CFB in Turkey: The right timing for the right technology". www.powerengineeringint.com. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Atilgan & Azapagic (2016), p. 177.

- "Towards Decarbonising Transport" (PDF). Agora Verkehrswende. pp. 131–134. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Veal, Lowana. "How Iceland is undoing carbon emissions for good". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Turkstat tables (2020), table 1.A(a)s1 cell G26 "solid fuels".

- Çınar (2020), p. 319.

- "Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions fall for second year in a row". Daily Sabah. Anadolu Agency. 31 March 2020.

Turkey's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 ... equivalent to 520.9 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2).

- "C Santrali, Türkiye'nin sera gazı emisyonunu yüzde 10 arttıracak" [C plant would increase Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions by 10%]. Elbistanın Sesi (in Turkish). 12 November 2020.

- Çınar (2020), p. 346.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 50.

- "Turkey shuts power plants for not installing filters". Anadolu Agency. 2 January 2020.

- Yerli̇ ve mi̇lli̇ enerji̇ poli̇ti̇kalari ekseni̇nde kömür [Local and national energy policies revolving around coal] (PDF) (Report). Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research. January 2019.

- Turkstat report (2020), pp. 59,60.

- "Global Methane Initiative: Turkey". www.globalmethane.org. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "Global coal power map". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Turkstat tables (2020), table 1.A(a)s1 cell G27.

- "Lira weakness weighs on Turkish coal generation margins". www.argusmedia.com. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Energy Deals 2019 (Report). PricewaterhouseCoopers. February 2020.

- "Outlook 2019: Turkish natural gas market set for potential 'de-liberalization' in 2019". Platts. S & P Global. 27 December 2018. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 110.

- Saygın et al (2019), p. 16.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 114.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 128.

- Saygın et al (2019), p. 17.

- "EU Fuel Quality Directive Preliminary Regulatory Impact Assessment (Pre-RIA)" (PDF). p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- European Commission (2020), p. 102.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 112.

- "Climate change is no joke". Daily Sabah. 19 October 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "CDP Turkey Climate Change and Water Report 2018". Carbon Disclosure Project. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Leading airlines failing to plan for long haul on climate, warns influential investor initiative". London School of Economics’ Grantham Research Institute. 5 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 143.

- OECD (2019).

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 141.

- Tech review seventh communication (2019), p. 28.

- Hoştut, Sibel; Deren van het Hof, Seçil (1 January 2020). "Greenhouse gas emissions disclosure: comparing headquarters and local subsidiaries". Social Responsibility Journal. 16 (6): 899–915. doi:10.1108/SRJ-11-2019-0377. ISSN 1747-1117.

- "Turkey's steel imports into Europe a 'problem' for the industry, says Liberty House boss". Sky News. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Eurofer seeking CVD on Turkish HRC". www.argusmedia.com. 29 May 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "How an EU Carbon Border Tax Could Jolt World Trade | BCG". BCG. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Methodology and detailed results: The external cost of fossil fuel use in power generation, heating and road transport in Turkey (PDF). Shura Energy Centre (Report). December 2020. p. 58.

- "#EuropeanGreenDeal could re-energize EU relations with #Turkey". EU Reporter. 13 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "The European Green Deal's Border Carbon Adjustment: Potential impacts on Turkey's exports to the European Union" (PDF).

- "Turkish cement sector exports surge 46 percent in first half". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Fourth biennial report (2019), p. 23.

- "Turkey's economy tips into recession as lira crisis bites". Reuters. 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Mercan, Muhammet. "Turkish industrial production grows 7.9%". ING Think. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

cement production ... shows the extent of activity in construction

- "Lack of intent in Turkey to tackle the climate crisis". www.duvarenglish.com. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- USDA (2020).

- "Strategies Regarding Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture Sector in Turkey". Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 294.

- "Turkey increases agricultural subsidies". UkrAgroConsult. 10 April 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "45.000 ton kömür alacak" [They will buy 45,000 tonnes of coal]. Enerji Ekonomisi. 3 July 2018. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Algedik, Önder. "Coal & Climate Change – 2017" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Everest, Bengü (11 May 2020). "Farmers' adaptation to climate-smart agriculture (CSA) in NW Turkey". Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00767-1. ISSN 1573-2975. S2CID 218573439.

- Yaman, Cevat (March 2020). "Investigation of greenhouse gas emissions and energy recovery potential from municipal solid waste management practices". Environmental Development. 33: 100484. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2019.100484.

- "Enhancing Climate Action in Turkey: Zero Waste Programme" (PDF).

- "Zero-waste town to be built in Turkey". Hürriyet Daily News. 15 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "One-fourth of wasted food could feed 870M people: expert". Anadolu Agency. 27 January 2021.

- Rodríguez-Fernández, Laura; Fernández Carvajal, Ana Belén; Bujidos-Casado, María (July 2020). "Allocation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Using the Fairness Principle: A Multi-Country Analysis". Sustainability. 12 (14): 5839. doi:10.3390/su12145839.

- "Current Policy Projections". Climate Action Tracker. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "EBRD to introduce new energy efficiency finance model". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Country Focus: Turkey: LNG Intake Rises [LNG Condensed]". www.naturalgasworld.com. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "All coal plants can be shut down!". www.duvarenglish.com. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Gürtürk, Mert (15 March 2019). "Economic feasibility of solar power plants based on PV module with levelized cost analysis". Energy. 171: 866–878. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.01.090.

- "Karapınar Solar Energy Plant goes online, Turkey". Construction Review Online. 30 September 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "The key to improving efficiency in Turkey's hydro power plants? Cooperation". blogs.worldbank.org. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Turkey, China, US to build pumped-storage hydro plant". Anadolu Agency. 9 April 2020.

- Taranto & Saygın (2018), p. 7.

- "Hydrogen to enter fuel, energy distribution network next year". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "National Hydrogen Association (Turkey)". National Hydrogen Association. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Turkey only outranked by China in direct utilization of geothermal energy". Think GeoEnergy – Geothermal Energy News. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- AKIN, Serhat; ORUCU, Yasemin; FRIDRIKSSON, Thrainn (February 2020). "Characterizing the Declining CO2 Emissions from Turkish Geothermal Power Plants" (PDF). PROCEEDINGS, 45th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering.

Typical emission factors at power plant commissioning range from 1,000 to 1,300 g/kWh

- "Analysis: Smart energy investments in Turkey". Smart Energy International. 29 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "12 global initiatives to beat back climate threats". Reuters. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Climate crisis: In the wake of a critical summit". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Renewables 2020 Global Status Report. REN21 (Report). p. 62. ISBN 978-3-948393-00-7.

- Aşıcı (2017), pp. 8,30.

- "Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Will Be Required". www.raillynews.com. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- Technology Roadmap: Low-Carbon Transition in the Cement Industry (PDF). 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Abstract on the potential GHG emissions reduction in Turkey through the cement industry" (PDF). Cementis GmbH. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Turkstat report (2020), p. 163.

- "Promoting Low Cost Energy Efficient Wooden Buildings in Turkey" (PDF). Global Environment Facility.

- "Decarbonization of industrial sectors: the next frontier". McKinsey. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "EU Carbon Capture and Storage Directive Preliminary Regulatory Impact Assessment (Pre-RIA)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Firtina Erti̇ş, İrem. "Application of Multi-criteria Decision Making for Geological Carbon Dioxide Storage Area in Turkey". Anadolu University Journal of Science and Technology A- Applied Sciences and Engineering. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- Bektaş, Abdulkadir (19 August 2020). "An Analysis of Energy-related Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Turkish Energy-intensive Sectors". doi:10.20944/preprints202008.0407.v1. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Isik, Mine; Sarica, Kemal; Ari, Izzet (1 October 2020). "Driving forces of Turkey's transportation sector CO2 emissions: An LMDI approach". Transport Policy. 97: 210–219. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.006. ISSN 0967-070X.

- Editorial (14 March 2020). "Zero emissions on top of Busworld Turkey's agenda. Isuzu, Karsan, Otokar in the spotlight". Sustainable Bus. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Vilnius signs contract to buy its first electric buses". Baltic Times. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "First ever self-driving e-bus in Istanbul, e-buses in provinces". Balkan Green Energy News. 23 April 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Brdulak, Anna; Chaberek, Grazyna; Jagodzinski, Jacek. "Development Forecasts for the Zero-Emission Bus Fleet in Servicing Public Transport in Chosen EU Member Countries".

- Aşıcı (2017), p. 32.

- "Green light for nationwide bicycle lane network". Daily Sabah. 13 December 2019.

- "Istanbul ferries to run 24/7 once plan gets green light from city council". www.duvarenglish.com. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Coastlink Conference | Navtek to Sponsor Coastlink". www.coastlink.co.uk. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Produced in Turkey, Anadolu Isuzu NPR10 first domestic EV Electric Vehicle". en.rayhaber.com. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "Turkey to become battery production hub: Minister". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Birpınar, Mehmet Emin (27 October 2020). "New green space trend in city centers: Vertical gardens". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Electric car sales in Turkey more than double in 1st 10 months". Daily Sabah. 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Turkey determined to boost hybrid, electric car sales". Yeni Şafak. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Turkey plans to create domestic car with electric engine". Azernews. 23 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Erdogan lays cornerstone for 1st Turkish car plant".

- "Turkey projected to have 2.5 mln electric cars by 2030 – Latest News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Saygın et al (2019), p. 76.

- "Indigenous automobile to add 50B euros to Turkish economy in 15 years". Daily Sabah. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Saygın et al (2019), p. 74.

- "After Oman, Careem exits Turkey too". MENAbytes. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Alex (16 January 2020). "BCAP invests in Turkish rideshare company Scotty". New Mobility. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Dijitalleşme taksi sektörünü nasıl etkiliyor?" [How will digitalisation affect the taxi sector]. Yeşil Lojistikçiler. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Saygın et al (2019), p. 22.

- "Turkey's electric car sales double in January–July – Latest News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Low-emission zones for Turkish cities in the works". Daily Sabah. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Turkey imposes recycling contribution fee". www.ey.com. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Number of electric, hybrid cars in Turkey triples in 2019". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Tesla reportedly pulls out of Turkish expansion plan due to new Trump trade war tariffs". Electrek. 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Millions of saplings set to be planted in Turkey's international forestation campaign". Daily Sabah. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- "The Carbon Brief Profile: Turkey". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Province-based Forest Cover (%)". Climate Change in Turkey. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "What can Africa learn from Turkey's reforestation?". World Economic Forum. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Wildfires in Izmir: a green plan for the city, an urban plan for the forests". www.youris.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Turkish soil at risk as worldwide desertification spreads". Daily Sabah. 19 June 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Soil Congress (2019), p. 49.

- Sonmez; et al. (March 2017). "Turkey's National Geospatial Soil Organic Carbon Information System" (PDF). Global Symposium on Soil Organic Carbon. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Soil Congress (2019), p. 107.

- Gross, Anna (29 September 2020). "Carbon offset market progresses during coronavirus". www.ft.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "Carbon Markets". turkishcarbonmarket.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Fourth biennial report (2019), pp. 10,11.

- Climate Action Tracker (2019), pp. 59–62.

- "Fossil fuel support country note". OECD.

- Seventh communication (2019), p. 30.

- Climate Action Tracker (2019), p. 63.

- Overview of recently adopted mitigation policies and climate-relevant policy responses to COVID-19 – 2020 Update. NewClimate Institute (Report). October 2020. p. 29.

- "Doubling Back and Doubling Down: G20 scorecard on fossil fuel funding". International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "Fossil Fuel Support - TUR". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "The Petcoke Podcast: Turkey's cement sector in 2020 | Argus Blog". www.argusmedia.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "New study finds incredibly high carbon pollution costs – especially for the US and India". The Guardian. 1 October 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Stoerk, Thomas; Wagner, Gernot; Ward, Robert E T (1 August 2018). "Policy Brief—Recommendations for Improving the Treatment of Risk and Uncertainty in Economic Estimates of Climate Impacts in the Sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report". Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 12 (2): 371–376. doi:10.1093/reep/rey005.

- "Multiple benefits from climate change mitigation: assessing the evidence". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Monetizing the Health Co-benefits of a Carbon Tax". Niskanen Center. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Gomez et al:Improving air (2019).

- Wei et al (2020).

- Isik, Mine. "Development of the Boğaziçi University Energy Modeling System (BUEMS) and its Application on Economic and Technological Implications of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions in Turkey". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Researchers examine Turkey to assess the impact of 2015 Paris climate commitments on a national economy". MIT. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Duyan, Özlem (19 March 2020). "A Voluntary Carbon Market in need of Carbon Pricing Policy in Turkey". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Bavbek, Gökşin (October 2016). "Assessing the Potential Effects of a Carbon Tax in Turkey" (PDF). Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (EDAM) Energy and Climate Change Climate Action Paper (6). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Carbon tariffs are EU's secret weapon in trade battle". Daily Telegraph. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Pollution Costs at Decade High Squeeze Industry, Coal in Europe". Bloomberg. 24 August 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Carbon Tariffs: A Climate Necessity?". Kluwer Regulating for Globalization. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Questions raised about EU climate financing as Turkey takes biggest share". devex. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Turkey: Notes from a state of (climatic) emergency". Climate Home. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "The EBRD's just transition initiative". European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

- OECD (2019), p. 32.

- "Taxing Energy Use" (PDF). OECD. 2019.

- Ayas (2020), p. 10.

- 19. Energy Consumption, Carbon Emissions and Income Inequality in Turkey. ISBN 978-3-631-80226-7.

- Uzar, Umut; Eyuboglu, Kemal (1 August 2019). "The nexus between income inequality and CO2 emissions in Turkey". Journal of Cleaner Production. 227: 149–157. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.169. ISSN 0959-6526.

- "Constitution of Turkey" (PDF). global.tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Teşkilat Yapısı". Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Turkey). Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "Turkey's dilemma: risky coal or clean development". Europe Beyond Coal. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Kigali Amendment". Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Turkey Announces Rules For Use Of Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases Listed In Kyoto Protocol". Mondaq. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Kleinschmidt, Julia (2019). "Setting up a new F-gas legislation in Turkey" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning.

- "Türkiye emisyonları azaltmayı hedefleyen 'Kigali Değişikliği'ni onaylıyor". Diken. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- TÜMÖZ GÜNDÜZ, Özge (2019). ODS and F-gas Regulation in Turkey and the Link to the Kigali Amendment (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning.

- Birpınar, Mehmet Emin (7 January 2021). "New trend in transportation: Micromobility". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Şahin & Türkkan (2019), p. 24.

- "Climate change: 'Trump effect' threatens Paris pact". BBC. 3 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "Track #7: Infrastructure, Cities and Local Action" (PDF).

- "How to Talk to a Populist About Climate Change". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Derviş, Kemal; Strauss, Sebastian (20 August 2019). "The real obstacle to climate action". Brookings.

- "Activists in Turkey demonstrate with call to 'unite behind the science' on climate change". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Turkey's first digital strike is for the climate". www.duvarenglish.com. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Turkey's 11-year-old activist demands grown-up action on climate change". Ahval. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "What the climate petition filed by 16 kids at the U.N. really means". Grist. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "New Turkish energy minister bullish for coal – but lira weakness limits market". Platts. 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "Turkey must move towards clean energy: Expert". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Turkey: Pandemic stresses need for green transformation".

- Sabadus, Aura. "SEE, Turkey braced for falling demand, bankruptcies amid emergency measures fallout". Icis. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "2017/11070" (PDF). Resmi Gazete. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "TETAŞ's Purchase of Electricity from Domestic Coal Fired Power Plants" (PDF). Çakmak Avukatlık Ortaklığı. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- MoEU (2012), pp. 28.

- Tech review seventh communication (2019), p. 20.

- SABAH, DAILY (20 September 2020). "Turkey's industrial development bank spearheads transition to zero-carbon economy". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Greens in Turkey Launch Green Party!". Yeşiller Partisi. 21 September 2020.

- "Climate Change and International Negotiations". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "A Statement of the Presidency on the Republic of Turkey's Position" (PDF). 22 November 2020.

- Bagatır, Bulut (13 December 2018). "Chief Climate Negotiator: Turkey Does Not Have a Luxury to Be a Laggard in Terms of Climate Action". İklim Haber. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Which countries have not ratified the Paris climate agreement?". Climate Home News. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- European Commission (2020), p. 100.

- "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Natural gas share of Turkey's electricity output down over 37% in 2019". Daily Sabah. 21 June 2020.

- "'Kara elmas'ı gün yüzüne çıkaran kömür firmaları TTK'ye de kazandırıyor" [Coal companies digging out black diamonds also benefit Turkish Hardcoal Enterprises]. www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "16 children, including Greta Thunberg, file landmark complaint to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Countries violate rights over climate change, argue youth activists in landmark UN complaint". UN News. 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Earthjustice (2019), p. 29.

- "Information Pack about the Optional Protocol to the Convention on theRights of the Child on a Communications Procedure (OP3 CRC)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Earthjustice (2019), p. 66.

- Kahn, Brian (23 September 2019). "It's Kids vs. the World in a Landmark New Climate Lawsuit". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Greta Thunberg Leads Young People in Climate Complaint to UN". Bloomberg. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Portuguese children sue 33 countries over climate change at European court". the Guardian. 3 September 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Action plans". www.covenantofmayors.eu. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Cengiz (2019), pp. 17,20.

- Şahin & Türkkan (2019), p. 28.

- Erden, Oğulkan; Erkartal, Pınar ÖKTEM (2 September 2019). "Greenwashing in Turkey: Sustainability as an Advertising Strategy in Architecture". A+Arch Design International Journal of Architecture and Design. 5 (1): 1–13.

- "Polling finds citizens in six belt and road countries want clean energy, not coal". E3G. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- Schulz, Florence (10 December 2019). "24 Turkish cities oppose Erdogan, support Paris Climate Agreement". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Bringing sustainable development into play: UNDP teams up with basketball federation to raise awareness – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Uyduranoglu, Ayse; Ozturk, Serda Selin (20 October 2020). "Public support for carbon taxation in Turkey: drivers and barriers". Climate Policy. 20 (9): 1175–1191. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1816887. ISSN 1469-3062. S2CID 222094247.

- Kılavuz, Emine; Dogan, Ibrahim (August 2020). "Economic growth, openness, industry and CO2 modelling: are regulatory policies important in Turkish economies?" (PDF).

- "DECARBONIZATION PATHWAYS FOR TURKEY 2020–2050 – MODELLING STUDY Terms of Reference" (PDF).

- Tech review third report (2019), p. 15.

- Fourth biennial report (2019), p. 33.

- "Turkey". International Carbon Action Partnership.

- "ETS Detailed Information: Turkey". International Carbon Action Partnership.

- "EU Emission Trading System Directive Preliminary Regulatory Impact Assessment (Pre-RIA)" (PDF). p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Akbas, H. E.; Canikli, S.; Yilmazer, S.; Sahin, B. S. (2020). "An examination of assurance practices on Turkish companies' greenhouse gas emissions disclosures". . Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting (JEFA). 7 (1): 44–53. doi:10.17261/Pressacademia.2020.1180.

- Tech review seventh communication (2019).

- Tech review seventh communication (2019), p. 23.

- Tech review seventh communication (2019), pp. 27–28.

- Inventory review (2020), pp. 31,32,33.

- Ayas (2020), p. 5.

- Pan, Guanna; Xu, Yuan; Ma, Jieqi (1 January 2021). "The potential of CO2 satellite monitoring for climate governance: A review". Journal of Environmental Management. 277: 111423. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111423. ISSN 0301-4797. PMID 33031999.

- Couture, Heather D. (11 August 2020). "How to Track the Emissions of Every Power Plant on the Planet from Space". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News.

UNFCCC

- Seventh National Communication (version 2) of Turkey under the UNFCCC (this is also the third biennial report). Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Report). August 2019.

- Report on the technical review of the seventh national communication of Turkey (PDF). UNFCCC (Report). June 2019.

- Report on the technical review of the third biennial report of Turkey (PDF). UNFCCC (Report). June 2019.

- Turkey's fourth biennial report. Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Report). December 2019.

- Report on the individual review of the inventory submission of Turkey submitted in 2019 (PDF). UNFCCC (Report). 26 May 2020.

- Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory report [TurkStat report]. Turkish Statistical Institute (Report). April 2020.

- "Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990 – 2018 common reporting format (CRF) tables [TurkStat tables]" (TUR_2020_2018_13042020_112534.xlsx). Turkish Statistical Institute. April 2020.

Other sources

- Atilgan, Burcin; Azapagic, Adisa (2016). "An integrated life cycle sustainability assessment of electricity generation in Turkey". Energy Policy. 93: 168–186. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.02.055.

- Ayas, Ceren (August 2020). Decarbonization of Turkey's economy: long-term strategies and immediate challenges (Report). CAN Europe, SEE Change Net, TEPAV.

- Cengiz, Pelin; Zırığ, Utku; Şimşek, Soner (January 2019). "Thematic Journalism in Turkey: Environmental-Ecological Reporting" (PDF). saha. Vol. Special Issue 2. pp. 16–23. ISSN 2149-7885.

- Scaling Up Climate Action series: Turkey (PDF) (Report). Climate Action Tracker. 2019.

- Turkey, Country Profile (Report). Climate Transparency. 2020.

- Çınar Engineering Consultancy (March 2020). Afşi̇n C Termi̇k Santrali, Açik Kömür İşletmesi̇ ve Düzenli̇ Depolama Alani Projesi̇: Nihai ÇED raporu [Afşin C power station, Opencast Mine and Landfill: Final EIA report] (Report) (in Turkish). Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Turkey).

- "Communication to the Committee on the Rights of the Child" (PDF). Earthjustice. 23 September 2019.

- Difiglio, Prof. Carmine; Güray, Bora Şekip; Merdan, Ersin (November 2020). Turkey Energy Outlook. iicec.sabanciuniv.edu (Report). Sabanci University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate (IICEC). ISBN 978-605-70031-9-5.

- The European environment — state and outlook 2020 (Report). European Environment Agency (EEA). 2019.

- Greenhouse gas mitigation scenarios for major emitting countries (PDF) (Report). New Climate Institute. 2019.

- OECD (February 2019). "OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019". OECD. OECD Environmental Performance Reviews. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en. ISBN 978-92-64-30974-6.

- EÜAŞ - A briefing for investors, insurers and banks (PDF) (Report). Europe Beyond Coal. January 2020.

- Şahin, Ümit; Türkkan, Seçil (January 2019). "Turkey's Climate Policies Have Reached a Deadlock: It Takes Courage to Resolve It" (PDF). saha. Vol. Special Issue 2. pp. 24–30. ISSN 2149-7885.

- Turkey 2020 Report (see chapters: 15 Energy, 27 Environment and Climate change) (PDF) (Report). European Commission. 2020.

- Saygın, Değer; Tör, Osman Bülent; Teimourzadeh, Saeed; Koç, Mehmet; Hildermeier, Julia; Kolokathis, Christos (December 2019). Transport sector transformation: Integrating electric vehicles into Turkey's distribution grids (PDF) (Report). SHURA Energy Transition Center.

- Emissions Gap Report 2019 (Report). UN Environment Programme. 19 November 2019.

- "Republic of Turkey Intended Nationally Determined Contribution" (PDF). 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

- Gümüşel, Deniz; Gündüzyeli, Elif. The Real Costs of Coal: Muğla (Report). CAN Europe.

- Republic of Turkey Climate Change Action Plan 2011 – 2023 (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Environment and Urbanization General Directorate of Environmental Management Climate Change Department. 2012.

- Taranto, Yael; Saygın, Değer (2018). Energy pricing and non-market flows in Turkey's energy sector (PDF) (Report). SHURA Energy Transition Center.

- Livestock Semi-annual Report Turkey (Report). USDA. 20 March 2020. TU2020-0004.

- Aşıcı, Ahmet A. (May 2017). Climate Friendly Green Economic Policies. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.25029.14562.

- Proceedings 10th International Soil Congress 2019 (PDF). Ankara. ISBN 978-605-63090-4-5.

- Gomez, Mara; Ertor, Pinar; Helgenberger, Sebastian; Nagel, Laura; Özenç, Bengisu; Özen, Efşan Nas (November 2019). Improving air quality and reducing health costs through renewable energy in Turkey (Report). COBENEFITS.

- Wei, Yi-Ming; Han, Rong; Wang, Ce; Yu, Biying; Liang, Qiao-Mei; Yuan, Xiao-Chen; Chang, Junjie; Zhao, Qingyu; Liao, Hua; Tang, Baojun; Yan, Jinyue (14 April 2020). "Self-preservation strategy for approaching global warming targets in the post-Paris Agreement era". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 1624. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.1624W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15453-z. PMC 7156390. PMID 32286257.

- 2019-2023 Strateji̇k Plani (PDF) (Report) (in Turkish). Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). May 2020.

External links

- UNFCCC Turkey documents

- Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data – Flexible Queries Annex I Parties

- Live carbon emissions from electricity generation

- Methane map

- Methane emissions

- Climate Watch: Turkey

- Climate Action Tracker: Turkey

- Capacity Development for the Implementation of a Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) System for Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Entegre Çevre Bilgi Sistemi (Integrated Environmental Information System) through which organizations report their emissions to the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization

- Carbon Market

- Business Council for Sustainable Development Turkey:Transition to Low Carbon Economy and Efficiency

- Soil Science Society of Turkey

- Soil Information System

- COBENEFITS

- Climate Laws