Food industry

The food industry is a complex, global network of diverse businesses that supplies most of the food consumed by the world's population. The term food industries covers a series of industrial activities directed at the production, distribution, processing, conversion, preparation, preservation, transport, certification and packaging of foodstuffs. The food industry today has become highly diversified, with manufacturing ranging from small, traditional, family-run activities that are highly labor-intensive, to large, capital-intensive and highly mechanized industrial processes. Many food industries depend almost entirely on local agriculture produce or fishing.[1]

It is challenging to find an inclusive way to cover all aspects of food production and sale. The UK Food Standards Agency describes it as "the whole food industry – from farming and food production, packaging and distribution, to retail and catering."[2] The Economic Research Service of the USDA uses the term food system to describe the same thing, stating: "The U.S. food system is a complex network of farmers and the industries that link to them. Those links include makers of farm equipment and chemicals as well as firms that provide services to agribusinesses, such as providers of transportation and financial services. The system also includes the food marketing industries that link farms to consumers, and which include food and fiber processors, wholesalers, retailers, and foodservice establishments."[3] The food industry includes:

- Agriculture: raising crops, livestock, and seafood

- Manufacturing: agrichemicals, agricultural construction, farm machinery and supplies, seed, etc.

- Food processing: preparation of fresh products for market, and manufacture of prepared food products

- Marketing: promotion of generic products (e.g., milk board), new products, advertising, marketing campaigns, packaging, public relations, etc.

- Wholesale and food distribution: logistics, transportation, warehousing

- Foodservice (which includes catering)

- Grocery, farmers' markets, public markets and other retailing

- Regulation: local, regional, national, and international rules and regulations for food production and sale, including food quality, food security, food safety, marketing/advertising, and industry lobbying activities

- Education: academic, consultancy, vocational

- Research and development: food technology

- Financial services: credit, insurance

Only subsistence farmers, those who survive on what they grow, and hunter-gatherers can be considered outside the scope of the modern food industry.

The dominant companies in the food industry have sometimes been referred to as Big Food, a term coined by the writer Neil Hamilton.[4][5][6][7]

Food production

Most food produced for the food industry comes from commodity crops using conventional agricultural practices. Agriculture is the process of producing food, feeding products, fiber and other desired products by the cultivation of certain plants and the raising of domesticated animals (livestock). On average, 83% of the food consumed by humans is produced using terrestrial agriculture.[8] Other food sources include aquaculture and fishing.[8]

The practice of agriculture is also known as "farming". Scientists, inventors, and others devoted to improving farming methods and implements are also said to be engaged in agriculture. 1 in 3 people worldwide are employed in agriculture,[9] yet it only contributes 3% to global GDP.[10] In 2017, on average, agriculture contributes 4% of national GDPs.[8] Global agricultural production is responsible for between 14 and 28% of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it one of the largest contributors to global warming, in large part due to conventional agricultural practices, including nitrogen fertilizers and poor land management.[8]

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants for food, fuel, fibre, and land reclamation. Agronomy encompasses work in the areas of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and soil science. Agronomy is the application of a combination of sciences. Agronomists today are involved with many issues including producing food, creating healthier food, managing the environmental impact of agriculture, and extracting energy from plants.[11]

Food processing

Food processing includes the methods and techniques used to transform raw ingredients into food for human consumption. Food processing takes clean, harvested or slaughtered and butchered components and uses them to produce marketable food products. There are several different ways in which food can be produced.

One-off production: This method is used when customers make an order for something to be made to their own specifications, for example, a wedding cake. The making of one-off products could take days depending on how intricate the design is.

Batch production: This method is used when the size of the market for a product is not clear, and where there is a range within a product line. A certain number of the same goods will be produced to make up a batch or run, for example a bakery may bake a limited number of cupcakes. This method involves estimating consumer demand.

Mass production: This method is used when there is a mass market for a large number of identical products, for example chocolate bars, ready meals and canned food. The product passes from one stage of production to another along a production line.

Just-in-time (JIT) (production): This method of production is mainly used in restaurants. All components of the product are available in-house and the customer chooses what they want in the product. It is then prepared in a kitchen, or in front of the buyer as in sandwich delicatessens, pizzerias, and sushi bars.

Industry influence

The food industry has a large influence on consumerism. Organizations, such as The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), have been criticized for accepting monetary donations from companies within the food industry, such as Coca-Cola.[12] These donations have been criticized for creating a conflict of interest and favoring an interest such as financial gains.[12]

Policy

In 2020 scientists reported that reducing emissions from the global food system is essential to achieving the Paris Agreement's climate goals.[13][14] In 2020, an evidence review for the European Union's Scientific Advice Mechanism found that, without significant change, emissions would increase by 30–40% by 2050 due to population growth and changing consumption patterns, and concluded that "the combined environmental cost of food production is estimated to amount to some $12 trillion per year, increasing to $16 trillion by 2050".[15] The IPCC's and the EU's reports concluded that adapting the food system to reduce greenhouse gas emissions impacts and food security concerns, while shifting towards a sustainable diet, is feasible.[8]

Regulation

Since World War II, agriculture in the United States and the entire national food system in its entirety has been characterized by models that focus on monetary profitability at the expense of social and environmental integrity.[16] Regulations exist to protect consumers and somewhat balance this economic orientation with public interests for food quality, food security, food safety, animal well-being, environmental protection and health.[17]

Proactive guidance

In 2020 researchers published projections and models of potential impacts of policy-dependent mechanisms of modulation, or lack thereof, of how, where, and what food is produced. They analyzed policy-effects for specific regions or nations such as reduction of meat production and consumption, reductions in food loss and waste, increases in crop yields and international land-use planning. Their conclusions include that raising agricultural yields is highly beneficial for biodiversity-conservation in sub-Saharan Africa while measures leading to shifts of diets are highly beneficial in North America and that global coordination and rapid action are necessary.[18][19][20]

Wholesale and distribution

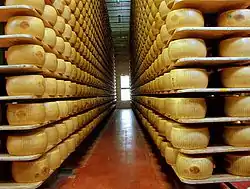

(A vast global cargo network connects the numerous parts of the industry. These include suppliers, manufacturers, warehousers, retailers and the end consumers.) Wholesale markets for fresh food products have tended to decline in importance in urbanizing countries, including Latin America and some Asian countries as a result of the growth of supermarkets, which procure directly from farmers or through preferred suppliers, rather than going through markets.

The constant and uninterrupted flow of product from distribution centers to store locations is a critical link in food industry operations. Distribution centers run more efficiently, throughput can be increased, costs can be lowered, and manpower better utilized if the proper steps are taken when setting up a material handling system in a warehouse.[21]

Retail

With worldwide urbanization,[22] food buying is increasingly removed from food production. During the 20th century, the supermarket became the defining retail element of the food industry. There, tens of thousands of products are gathered in one location, in continuous, year-round supply.

Food preparation is another area where the change in recent decades has been dramatic. Today, two food industry sectors are in apparent competition for the retail food dollar. The grocery industry sells fresh and largely raw products for consumers to use as ingredients in home cooking. The food service industry, by contrast, offers prepared food, either as finished products or as partially prepared components for final "assembly". Restaurants, cafes, bakeries and mobile food trucks provide opportunities for consumers to purchase food.

In the 21st century online grocery stores emerged and digital technologies for community-supported agriculture have enabled farmers to directly sell produce.[23] Some online grocery stores have voluntarily set social goals or values beyond meeting consumer demand and the accumulation of profit.[24]

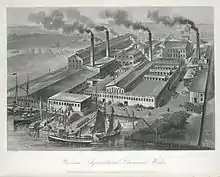

Food industry technologies

Modern food production is defined by sophisticated technologies. These include many areas. Agricultural machinery, originally led by the tractor, has practically eliminated human labor in many areas of production. Biotechnology is driving much change, in areas as diverse as agrochemicals, plant breeding and food processing. Many other types of technology are also involved, to the point where it is hard to find an area that does not have a direct impact on the food industry. As in other fields, computer technology is also a central force.

Marketing

As consumers grow increasingly removed from food production, the role of product creation, advertising, and publicity become the primary vehicles for information about food. With processed food as the dominant category, marketers have almost infinite possibilities in product creation. Of the food advertised to children on television 73% is fast or convenience foods.[25]

Labor and education

Until the last 100 years, agriculture was labor-intensive. Farming was a common occupation and millions of people were involved in food production. Farmers, largely trained from generation to generation, carried on the family business. That situation has changed dramatically today. In America in 1870, 70-80 percent of the US population was employed in agriculture.[26] As of 2008, less than 2 percent of the population is directly employed in agriculture,[27][28] and about 80% of the population lives in cities. The food industry as a complex whole requires an incredibly wide range of skills. Several hundred occupation types exist within the food industry.

By country

- Food industry in Azerbaijan

- Food industry in India

- Food industry of Russia

- Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (Moldova)

- Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (Ireland)

See also

General:

- Agricultural economics

- Dietary supplement

- Environmental impact of agriculture

- Factory farming

- Flavor masker

- Food and Bioprocess Technology

- Food chemistry

- Food engineering

- Food fortification

- Food grading

- Food microbiology

- Food packaging

- Food preservation

- Food rheology

- Food safety

- Food science

- Food storage

- Food supplements

- Food technology

- Geography of food

- Local food

- Nutraceutical

- Nutrification (aka food enrichment or fortification)

- Produce

Book, film, TV and web-related exposés and critiques of the food industry:

- Criticism of fast food

- Eat This, Not That (nonfiction series published in Men's Health magazine)

- Fast Food Nation (2001 nonfiction book)

- Chew On This (2005 book adaptation of Fast Food Nation for younger readers)

- Fast Food Nation (2006 documentary film)

- Food, Inc. (2008 documentary film)

- Panic Nation (2006 nonfiction book)

- Super Size Me (2004 documentary film)

- Forks over Knives (2011 documentary film)

- The Jungle (1906 novel by Upton Sinclair that exposed health violations and unsanitary practices in the American meat packing industry during the early 20th century, based on an investigation he did for a socialist newspaper)

References

- Parmeggiani, Lougi, ed. (1983). "???". Encyclopædia of Occupational Health and Safety (3rd ed.). Geneva: International Labour Office. ISBN 9221032892.

- "Industry". Food Standards Agency (UK).

- "Food market structures: Overview". Economic Research Service (USDA).

- Sue Booth; John Coveney (19 February 2015). Food Democracy: From consumer to food citizen. Springer. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-981-287-423-8.

- Gray, Allison; Hinch, Ronald (1 October 2019). A Handbook of Food Crime: Immoral and Illegal Practices in the Food Industry and What to Do About Them. Policy Press. pp. 371–. ISBN 978-1-4473-5628-8.

- Booth, Sue; Coveney, John (2015), Booth, Sue; Coveney, John (eds.), "'Big Food'—The Industrial Food System", Food Democracy: From consumer to food citizen, SpringerBriefs in Public Health, Singapore: Springer, pp. 3–11, doi:10.1007/978-981-287-423-8_2, ISBN 978-981-287-423-8, retrieved 2020-11-26

- Stuckler, David; Nestle, Marion (2012-06-19). "Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health". PLOS Medicine. 9 (6): e1001242. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3378592. PMID 22723746.

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019.

- "Labour" (PDF). FAO.org. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "Macroeconomy" (PDF). FAO.org. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- "I'm An Agronomist!". Imanagronomist.net. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- Brody, Howard (2016-08-01). "Professional medical organizations and commercial conflicts of interest: ethical issues". Annals of Family Medicine. 8 (4): 354–358. doi:10.1370/afm.1140. ISSN 1544-1717. PMC 2906531. PMID 20644191.

- "Reducing global food system emissions key to meeting climate goals". phys.org. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Clark, Michael A.; Domingo, Nina G. G.; Colgan, Kimberly; Thakrar, Sumil K.; Tilman, David; Lynch, John; Azevedo, Inês L.; Hill, Jason D. (6 November 2020). "Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets". Science. 370 (6517): 705–708. doi:10.1126/science.aba7357. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33154139. S2CID 226254942. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (2020). A sustainable food system for the European Union (PDF). Berlin: SAPEA. p. 39. doi:10.26356/sustainablefood. ISBN 978-3-9820301-7-3.

- Schattman, Rachel. "Sustainable Food Sourcing and Distribution in the Vermont-Regional Food System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Szajkowska, Anna (March 2012). Regulating Food Law: Risk Analysis and the Precautionary Principle as General Principles of EU Food Law. Wageningen Academic Pub. ISBN 9789086861941. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- "Global food industry on course to drive rapid habitat loss – research". the Guardian. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Current food production systems could mean far-reaching habitat loss". phys.org. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- Williams, David R.; Clark, Michael; Buchanan, Graeme M.; Ficetola, G. Francesco; Rondinini, Carlo; Tilman, David (21 December 2020). "Proactive conservation to prevent habitat losses to agricultural expansion". Nature Sustainability: 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-00656-5. ISSN 2398-9629. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Boosting efficiency at the DC". Grocery Headquarters. Archived from the original on 2010-03-27. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- "World Urbanization Prospects: The 2003 Revision". Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (United Nations).

- Foote, Natasha (2 April 2020). "Innovation spurred by COVID-19 crisis highlights 'potential of small-scale farmers'".

- "Amid Pandemic, Local Company Delivering Meat And Fresh, Organic Sustainable Foods". 22 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Kunkel, Dale (2009). "The Impact of Industry Self-Regulation on the Nutritional Quality of Foods Advertised to Children on Television" (PDF). Children Now.

- Neat Facts About United States Agriculture Archived 2014-03-14 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved November 19, 2013

- "Employment by major industry sector". Bls.gov. 2013-12-19. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- "Extension". Csrees.usda.gov. 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

Further reading

- Nestle, M. (2013). Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. California Studies in Food and Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95506-6. 534 pages.

- Vasconcellos, J.A. (2003). Quality Assurance for the Food Industry: A Practical Approach. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-49810-1. 448 pages.

- Kress-Rogers, E.; Brimelow, C.J.B. (2001). Instrumentation and Sensors for the Food Industry. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. Woodhead. ISBN 978-1-85573-560-6. 836 pages.

- Traill, B.; Pitts, E. (1998). Competitiveness in the Food Industry. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7514-0431-9. 301 pages.

- Food Fight: The Inside Story of the Food Industry

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Food industry. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Food industry |

- "The Food Industry Center". University of Minnesota.

- "Economic Issues with the Persistence of Profitability in Food Businesses and Agricultural Businesses" (PDF). Ksre.ksu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- "FoodIndustry.Com".

- Center for Sustainable Systems. "U.S. Food System Factsheet" (PDF). University of Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-06.