Monarchy of Belgium

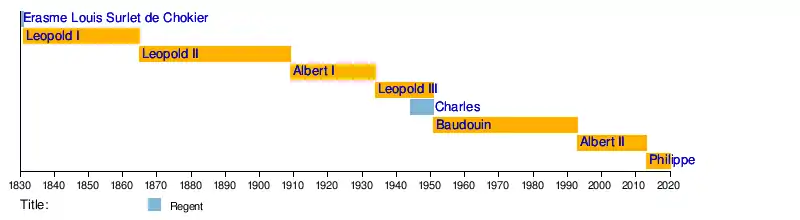

The Monarchy of Belgium is a constitutional, hereditary, and popular monarchy of Belgium whose incumbent is titled the King or Queen of the Belgians (Dutch: Koning(in) der Belgen, French: Roi / Reine des Belges, German: König(in) der Belgier) and serves as the country's head of state. There have been seven Belgian monarchs since independence in 1830.

| King of the Belgians | |

|---|---|

| Koning der Belgen (Dutch) Roi des Belges (French) König der Belgier (German) | |

| |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Philippe since 21 July 2013 | |

| Details | |

| Style | His Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Princess Elisabeth, Duchess of Brabant |

| First monarch | Leopold I |

| Formation | 21 July 1831 |

| Residence | Royal Palace of Brussels Royal Castle of Laeken |

| Website | The Belgian Monarchy |

| House of Belgium | |

|---|---|

Belgian Royal Coat Arms | |

| Parent house | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Place of origin | Belgium |

| Founded | 21 July 1831 |

| Founder | Leopold I |

| Current head | Philippe |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Belgium |

The incumbent, Philippe, ascended the throne on 21 July 2013, following the abdication of his father.

Origins

When the Belgians became independent in 1830 the National Congress chose a constitutional monarchy as the form of government. The Congress voted on the question on 22 November 1830, supporting monarchy by 174 votes to 13. In February 1831, the Congress nominated Louis, Duke of Nemours, the son of the French king Louis-Philippe, but international considerations deterred Louis-Philippe from accepting the honour for his son.

Following this refusal, the National Congress appointed Erasme-Louis, Baron Surlet de Chokier to be the Regent of Belgium on 25 February 1831. Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was designated as King of the Belgians by the National Congress and swore allegiance to the Belgian constitution in front of Saint James's Church at Coudenberg Palace in Brussels on 21 July.[1] This day has since become a national holiday for Belgium and its citizens.

Hereditary and constitutional

As a hereditary constitutional monarchy system, the role and operation of Belgium's monarchy is governed by the Constitution. The royal office of King is designated solely for a descendant of the first King of the Belgians, Leopold I.

Since he is bound by the Constitution (above all other ideological and religious considerations, political opinions and debates and economic interests) the King is intended to act as an arbiter and guardian of Belgian national unity and independence.[2] Belgium's monarchs are inaugurated in a purely civil swearing-in ceremony.

The Kingdom of Belgium was never an absolute monarchy. Nevertheless, in 1961, the historian Ramon Arango, wrote that the Belgian monarchy is not "truly constitutional".[3]

Leopold I, Leopold II and Albert I

King Leopold I was head of Foreign Affairs "as an ancien régime monarch", the foreign ministers having the authority to act only as ministers of the king.[4] Leopold I quickly became one of the most important shareholders of the Société Générale de Belgique.[5]

Leopold's son, King Leopold II is chiefly remembered for the founding and capitalization of the Congo Free State as a personal fiefdom. There was scandal when the atrocities in the Congo Free State were made public, causing the Free State to be taken over by the Belgian Government. Many Congolese were killed as a result of Leopold's policies in the Congo before the reforms of direct Belgian rule.[6][7][8] The Free State scandal is discussed at the Museum of the Congo at Tervuren in Belgium.[9]

On several occasions Leopold II publicly expressed disagreement with the ruling government (e.g. on 15 August 1887 and in 1905 against Prime Minister Auguste Beernaert)[10] and was accused by Yvon Gouet of noncompliance with the country's parliamentary system.[11]

Leopold III and Baudouin

Louis Wodon (the chef de cabinet of Leopold III from 1934 to 1940), thought the King's oath to the Constitution implied a royal position "over and above the Constitution". He compared the King to a father, the head of a family, "Regarding the moral mission of the king," said Arango, "it is permissible to point to a certain analogy between his role and that of a father, or more generally, of parents in a family. The family is, of course, a legal institution as is the state. But what would a family be where everything was limited among those who compose it to simply legal relationships? In a family when one considers only legal relationships one comes very close to a breakdown in the moral ties founded on reciprocal affection without which a family would be like any other fragile association"[12] According to Arango, Leopold III of Belgium shared these views about the Belgian monarchy.

In 1991, towards the end of the reign of Baudouin, Senator Yves de Wasseige, a former member of the Belgian Constitutional Court, cited four points of democracy which the Belgian Constitution lacks:[13]

- the King chooses the ministers,

- the King is able to influence the ministers when he speaks with them about bills, projects and nominations,

- the King promulgates bills, and,

- the King must agree to any change of the Constitution

Constitutional, political, and historical consequences

The Belgian monarchy was from the beginning a constitutional monarchy, patterned after that of the United Kingdom.[14] Raymond Fusilier wrote the Belgian regime of 1830 was also inspired by the French Constitution of the Kingdom of France (1791–1792), the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the old political traditions of both Walloon and Flemish provinces.[15] "It should be observed that all monarchies have suffered periods of change as a result of which the power of the sovereign was reduced, but for the most part those periods occurred before the development of the system of constitutional monarchy and were steps leading to its establishment."[16] The characteristic evidence of this is in Great Britain where there was an evolution from the time when kings ruled through the agency of ministers to that time when ministers began to govern through the instrumentality of the Crown.

Unlike the British constitutional system, in Belgium "the monarchy underwent a belated evolution" which came "after the establishment of the constitutional monarchical system"[17] because, in 1830–1831, an independent state, parliamentary system and monarchy were established simultaneously. Hans Daalder, professor of political science at the Rijksuniversiteit Leiden wrote: "Did such simultaneous developments not result in a possible failure to lay down the limits of the royal prerogatives with some precision—which implied that the view of the King as the Keeper of the Nation, with rights and duties of its own, retained legitimacy?"[18]

For Raymond Fusilier, the Belgian monarchy had to be placed—at least in the beginning—between the regimes where the king rules and those in which the king does not rule but only reigns. The Belgian monarchy is closer to the principle "the King does not rule",[19] but the Belgian kings were not only "at the head of the dignified part of the Constitution".[20] The Belgian monarchy is not merely symbolic, because it participates in directing affairs of state insofar as the King's will coincides with that of the ministers, who alone bear responsibility for the policy of government.[21] For Francis Delpérée, to reign does not only mean to preside over ceremonies but also to take a part in the running of the State.[22] The Belgian historian Jean Stengers wrote that "some foreigners believe the monarchy is indispensable to national unity. That is very naive. He is only a piece on the chessboard, but a piece which matters.[23]

List of kings of the Belgians

The monarchs of Belgium originally belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The family name was changed by Albert I in 1920 to the House of Belgium as a result of anti-German sentiment.

This is a family tree of the Kings of the Belgians, hereditary, constitutional monarchs of Belgium as defined by the Belgian Constitution.

| Francis Duke of Saxe- Coburg-Saalfeld 1750–1806 r.1800–1806 | Augusta Reuss of Ebersdorf 1757–1831 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charlotte of Wales 1796–1817 | Leopold I King of the Belgians 1790–1865 r.1831-1865 | Louise of Orléans 1812–1850 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis Philippe 1833–1834 | Leopold II King of the Belgians 1835–1909 r.1865-1909 | Marie Henriette of Austria 1836–1902 | Philippe Count of Flanders 1837–1905 | Marie of Hohenzollern- Sigmaringen 1845–1912 | Carlota of Mexico 1840–1927 | Maximilian I Emperor of Mexico 1832–1867 r.1863–1867 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 1844–1921 | Louise of Belgium 1858–1924 | Leopold Duke of Brabant 1859-1869 | Rudolf Cr. Prince of Austria 1858–1889 | Stéphanie of Belgium 1864–1945 | Albert I King of the Belgians 1875–1934 r.1909-1934 | Elisabeth of Bavaria 1876–1965 | Baudouin of Flanders 1869-1891 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Astrid of Sweden 1905–1935 | Leopold III King of the Belgians 1901–1983 r.1934-1951 | Lilian Princess of Réthy 1916–2002 | Charles of Flanders Prince Regent 1903–1983 r.1944–1950 | Marie José of Belgium 1906–2001 | Umberto II King of Italy 1904–1983 r.1946 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jean Grand Duke of Luxembourg 1921–2019 r.1964–2000 | Joséphine Charlotte of Belgium 1927–2005 | Fabiola de Mora y Aragón 1928–2014 | Baudouin King of the Belgians 1930–1993 r.1951-1993 | Albert II King of the Belgians 1934– r.1993–2013 | Paola of Belgium 1937- | Alexander of Belgium 1942–2009 | Léa of Belgium 1951- | Marie Christine of Belgium 1951- | Marie Esméralda of Belgium 1956- | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mathilde of Belgium 1973- | Philippe King of the Belgians 1960– r.2013–present | Astrid of Belgium 1962- Archduchess of Austria-Este | Lorenz of Belgium Archduke of Austria-Este 1955- | Laurent of Belgium 1963- | Claire of Belgium 1974- | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louise of Belgium 2004- | Nicolas of Belgium 2005- | Aymeric of Belgium 2005- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elisabeth Duchess of Brabant 2001- | Gabriel of Belgium 2003- | Emmanuel of Belgium 2005- | Eléonore of Belgium 2008- | Amedeo of Belgium Archduke of Austria-Este 1986- | Maria Laura Archduchess of Austria-Este 1988- | Joachim of Belgium Archduke of Austria-Este 1991- | Luisa Maria Archduchess of Austria-Este 1995- | Laetitia Maria Archduchess of Austria-Este 2003- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Title

The proper title of the Belgian monarch is King of the Belgians rather than King of Belgium. The title indicates a popular monarchy linked to the people of Belgium (i.e., a hereditary head of state; yet ratified by popular will) rather than to territory or state. The Latin translation of King of Belgium would have been Rex Belgii, which, from 1815, was the name for the king of the Netherlands. Therefore, the separatists who founded Belgium chose Rex Belgarum.

Belgium is the only extant European monarchy in which the heir to the throne does not ascend immediately upon the death or abdication of his or her predecessor. According to Article 91 of the Belgian constitution, the heir accedes to the throne only upon taking a constitutional oath before a joint session of the two Houses of Parliament.[24] The joint session has to be held within ten days of the death or abdication of the previous monarch. The new Belgian monarch is required to take the Belgian constitutional oath, "I swear to observe the Constitution and the laws of the Belgian people, to maintain the national independence and the integrity of the territory," which is uttered in the three official languages: French, Dutch, and German.

Members of the Belgian royal family are often known by two names: a Dutch and a French one. For example, the current monarch is called 'Philippe' in French and 'Filip' in Dutch; the fifth King of the Belgians was 'Baudouin' in French and 'Boudewijn' in Dutch.

In contrast to King Philippe's title of "King of the Belgians", Princess Elisabeth is called "Princess of Belgium" as the title "Prince of the Belgians" does not exist. She is also Duchess of Brabant, the traditional title of the heir apparent to the Belgian throne. This title precedes the title "Princess of Belgium".

In the other official language of German, monarchs are usually referred to by their French names. The same is true for English with the exception of Leopold, where the accent is removed for the purpose of simplicity.

Because of the First World War and the resultant strong anti-German sentiment, the family name was changed in 1920 from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to van België, de Belgique, or von Belgien ("of Belgium"), depending upon which of the country's three official languages (Dutch, French, and German) is in use. It is this family name which is used on the identity cards and in all official documents by Belgium's royalty (e.g. marriage licenses). In addition to this change of name, the armorial bearings of Saxony were removed from the Belgian royal coat of arms (see above). Other Coburgers from the multi-branched Saxe-Coburg family have also changed their name, such as George V, who adopted the family name of Windsor after the British royal family’s place of residence.[25]

Nevertheless, the Royal Decree published on 19 July and signed on 12 July 2019 by King Philip, reinstated the Saxonian escutcheon in the all royal versions of the family's coat of arms.[26][27] The reinstatement of the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha main royal arms occurred shortly after the visit of King Philip and Queen Mathilde to the ancestral Friedenstein Castle.[28]

Constitutional role

The Belgian monarchy symbolises and maintains a feeling of national unity by representing the country in public functions and international meetings.

In addition, the monarch has a number of responsibilities in the process of the formation of the Government. The procedure usually begins with the nomination of the "Informateur" by the monarch. After the general election the Informateur officially informs the monarch of the main political formations which may be available for governance. After this phase, the monarch can appoint another "informateur" or appoint a "Formateur", who will have the charge of forming a new government, of which he or she generally becomes the Prime Minister.

Article 37 of the Constitution of Belgium vests the "federal executive power" in the monarch. Under Section III, this power includes the appointment and dismissal of ministers, the implementation of the laws passed by the Federal Parliament, the submission of bills to the Federal Parliament and the management of international relations. The monarch sanctions and promulgates all laws passed by Parliament. In accordance with Article 106 of the Belgian Constitution, the monarch is required to exercise his powers through the ministers. His acts are not valid without the countersignature of the responsible minister, who in doing so assumes political responsibility for the act in question. This means that federal executive power is exercised in practice by the Federal Government, which is accountable to the Chamber of Representatives in accordance with Article 101 of the Constitution.

The monarch receives the prime minister at the Palace of Brussels at least once a week, and also regularly calls other members of the government to the palace in order to discuss political matters. During these meetings, the monarch has the right to be informed of proposed governmental policies, the right to advise, and the right to warn on any matter as the monarch sees fit. The monarch also holds meetings with the leaders of all the major political parties and regular members of parliament. All of these meetings are organised by the monarch's personal political cabinet which is part of the Royal Household.

The monarch is the Commander-in-Chief of the Belgian Armed Forces and makes appointments to the higher positions. The names of the nominees are sent to the monarch by the Ministry of Defence. The monarch's military duties are carried out with the help of the Military Household which is headed by a General office. Belgians may write to the monarch when they meet difficulties with administrative powers.

The monarch is also one of the three components of the federal legislative power, in accordance with the Belgian Constitution, together with the two chambers of the Federal Parliament: the Chamber of Representatives and the Senate. All laws passed by the Federal Parliament must be signed and promulgated by the monarch.

Previously, children of the King were entitled to a seat in the senate (Senator by right) when they were 18. This right was abolished in 2014 as part of the Sixth Belgian state reform.

Inviolability

Article 88 of the Belgian Constitution provides that "the King's person is inviolable, his ministers are responsible". This means that the King cannot be prosecuted, arrested, or convicted of crimes, cannot be summoned to appear before a civil court, and is not accountable to the Federal Parliament. This inviolability was deemed incompatible, however, with Article 27 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court which states that official capacity shall not exempt a person from criminal responsibility under the statute.[29]

Traditions

The Court still keeps some old traditions, most famous is the tradition that the Reigning King of the Belgians becomes the godfather of a seventh son and the Queen the godmother of a seventh daughter.[30] The child is then given the name of the Sovereign and receives a gift from the palace and Burgomaster of the city.[31] Similar traditions are attached to the Russian Tsar and the President of Argentina.[32] Another tradition is the centuries-old ceremonial welcome the new king receives in the country during the Joyous Entry; this tradition apparently dates back to the Dukes of Brabant.

Popular support

The Belgian monarchy enjoys a lower degree of support than other European monarchies, and is often questioned.[33] Popular support for the monarchy had historically been higher in Flanders and lower in Wallonia. The generally pro-monarchy Catholic Party and later Christian Social Party dominated in Flanders, while the more industrialised Wallonia had more support for the Belgian Labour Party and later Socialist Party. For example, the 1950 referendum saw Flanders voting strongly in favour of King Leopold III returning, whereas Wallonia was largely against. However, in recent decades these roles have reversed, as religiosity in Flanders has decreased and the King is seen as protecting the country against (Flemish) separatism and the country's partition.[34]

Royal Household

The King's Household (Dutch: Het Huis van de Koning, French: La Maison du Roi, German: Das Haus des Königs) was reorganised in 2006, and consists of seven autonomous departments and the Court's Steering Committee. Each Head of Department is responsible for his department and is accountable to the King.

The following departments currently make up the King's Household:

- the Department for Economic, Social and Cultural Affairs

- the King's Cabinet

- the King's Military Household

- the King's Civil List

- the Department for Foreign Relations

- the Department of the Protocol of the Court

- the Department of Petitions

The King's Chief of Cabinet is responsible for dealing with political and administrative matters and for maintaining the relations with the government, trade unions and industrial circles. In relation to the King, the Chief assists in keeping track of current events; informs regarding all aspects of Belgian life; proposes and prepares audiences; assists in preparing speeches and informs the King about developments in international affairs. The Chief of Cabinet is assisted by the Deputy and Legal Adviser, the Press Adviser and the Archivist. The incumbent Chief of Cabinet is Baron Frans Van Daele, former Chief of Cabinet of President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy.

The Head of the King's Military Household assists the King in fulfilling his duties in the field of defence. He informs the King about all matters of security, defence policy, the views of Belgium's main partner countries and all aspects of the Belgian Armed Forces. He organises the King's contacts with the Armed Forces, advises in the fields of scientific research and police and coordinates matters with patriotic associations and former service personnel. The Military Household is also responsible for managing the Palace's computer system. The Head of the Military Household is a General Officer, currently General Jef Van den put and assisted by an adviser, currently Lieutenant-Colonel Aviator Serge Vassart. The King's Aides-de-Camp and the King's Equerries are also attached to the Military Household.

The King's aides-de-camp are senior officers chosen by the monarch and charged with carrying out certain tasks on his behalf, such as representing him at events. The King's Equerries are young officers who take turns preparing the King's activities, informing him about all the aspects that may be important to him and providing any other useful services such as announcing visitors. The equerry accompanies the King on his trips except for those of a strictly private nature.

The Intendant of the King's Civil List is responsible for managing the material, financial and human resources of the King's Household. He is assisted by the Commandant of the Royal Palaces, the Treasurer of the King's Civil List and the Civil List Adviser. The Intendant of the Civil List also advises the King in the field of energy, sciences and culture and administers the King's hunting rights. The Commandant of the Royal Palaces is mainly in charge, in close cooperation with the Chief of Protocol, of the logistic support of activities and the maintenance and cleaning of the Palaces, Castles and Residences. He is also Director of the Royal Hunts.

The Chief of Protocol is charged with organising the public engagements of the King and the Queen, such as audiences, receptions and official banquets at the Palace, as well as formal activities outside of the Palace. He is assisted by the Queen's Secretary, who is mainly responsible for proposing and preparing the Queen's audiences and visits.

The Head of the Department for Economic, Social and Cultural Affairs advises the King in the economic, social and cultural fields. He is also responsible for providing coordination between the various Households and Services and for organising and minuting the meetings of the Steering Committee. The Head of the Department for Foreign Relations informs the King of developments in international policy, assists the King from a diplomatic viewpoint on royal visits abroad and prepares the King's audiences in the international field. He is also responsible for maintaining contacts with foreign diplomatic missions. The Head of the Department of Petitions is charged with processing petitions and requests for social aid addressed the King, the Queen or other members of the royal family. He is also responsible for the analysis and coordination of royal favours and activities relating to jubilees, and advises the King in the fields for which he is responsible.

For the personal protection of the King and the royal family, as well as for the surveillance of the royal estates, the Belgian Federal Police at all times provides a security detail to the Royal Palace, commanded by a chief police commissioner. The other members of the royal family have a service at their disposal.

Members of the Belgian royal family

|

|

|

Members of the royal family hold the title of Prince (Princess) of Belgium, with the style of Royal Highness. Prior to World War I, they used the additional titles of Prince (Princess) of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duke (Duchess) of Saxony as members of the House of Wettin.

The title Prince or Princess of Belgium is a specific noble title within the Belgian nobility reserved for members of the Belgian royal family. Originally the Royal Decree of 14 March 1891 reserved this title for all persons descending in the direct male line from king Leopold I. The royal decree also automatically granted the title to the princesses who joined the Belgian royal family by their marriage to a Prince of Belgium. This royal decree was amended by the Royal Decree of 2 December 1991, which reserved the title for the direct male and female descendants of Albert II and abolished the Salic Law with regards to its granting. The Royal Decree of 12 November 2015, published in the Belgian official journal on 24 November 2015 abolished the aforementioned Royal Decree of 1991 and restricts new grants of this title to the children and grandchildren of the reigning monarch, and to the children and grandchildren of the crownprince(ss). The spouse of a Prince or Princess of Belgium is no longer automatically granted the title but he or she can still be granted the title by royal decree on an individual basis.[35] Prior to this, all descendants of Albert II were entitled to the title of prince or princess.[36]

Philippe (born 15 April 1960) is King of the Belgians. He married, on 4 December 1999, Jonkvrouwe Mathilde d'Udekem d'Acoz, who was created HRH Princess Mathilde of Belgium a day before their wedding, after which she also took the title Duchess of Brabant as the wife of the Duke of Brabant, and became, from 21 July 2013, Queen Mathilde of the Belgians. She is a daughter of the late Patrick d'Udekem d'Acoz (made a count prior to the wedding) and his wife, Countess Anna Maria Komorowska. They have four children:

- HRH Princess Elisabeth, Duchess of Brabant, who will inherit the throne after her father due to a 1991 act of succession which established absolute (gender-neutral) primogeniture, altering the order of succession from "eldest son" to "eldest child".

- HRH Prince Gabriel of Belgium

- HRH Prince Emmanuel of Belgium

- HRH Princess Eléonore of Belgium

Other members of the royal family

- HM King Albert II (born 6 June 1934). He was the king between 1993 (following the death of his brother King Baudouin) and 21 July 2013, the Belgian National Day, when he abdicated in favour of his son Philippe, Duke of Brabant, because of ill health. On 2 July 1959, he married Donna Paola Ruffo di Calabria (born 11 September 1937) in Brussels, who became HRH Princess Paola of Belgium, Princess of Liège, and after 1993, became Queen Paola of the Belgians. She is the daughter of Fulco VIII, Prince Ruffo di Calabria, 6th Duke of Guardia Lombarda (1884–1946) and his wife, Luisa Gazelli dei Conti di Rossana e di Sebastiano (1896–1989). Together they have three children, the current king (see above), a daughter and another son:

- HI&RH Princess Astrid, Archduchess of Austria-Este (born 5 June 1962). She is the wife of HI&RH Prince Lorenz of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este, Prince Royal of Hungary and Bohemia, whom she married on 22 September 1984 and who was created a prince of Belgium in 1995. Princess Astrid, with her own descendants, is before her brother Laurent in the order of succession to the Belgian throne, due to the 1991 act of succession mentioned above. They have five children:

- HI&RH Prince Amedeo of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este. He married Elisabetta Maria Rosboch von Wolkenstein on 5 July 2014. They have one daughter and one son:

- HI&RH Archduchess Anna Astrid of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Archduke Maximilian of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Princess Maria Laura of Belgium, Archduchess of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Prince Joachim of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Princess Luisa Maria of Belgium, Archduchess of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Princess Laetitia Maria of Belgium, Archduchess of Austria-Este

- HI&RH Prince Amedeo of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este. He married Elisabetta Maria Rosboch von Wolkenstein on 5 July 2014. They have one daughter and one son:

- HRH Prince Laurent of Belgium (born 19 October 1963). He married Claire Coombs, an Anglo-Belgian former land surveyor, on 12 April 2003, who was created HRH Princess Claire of Belgium 11 days before their wedding. They have one daughter and two sons:

- HRH Princess Delphine of Belgium (born 22 February 1968). She is the non-marital daughter of King Albert II by his former mistress, Baroness Sybille de Selys Longchamps. After winning a paternity case in 2020, she and her children were elevated to the rank of prince/princess of Belgium by a court ruling on 1 October 2020. She has been in a relationship with James O'Hare since 2000. They have one daughter and one son:

- HI&RH Princess Astrid, Archduchess of Austria-Este (born 5 June 1962). She is the wife of HI&RH Prince Lorenz of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este, Prince Royal of Hungary and Bohemia, whom she married on 22 September 1984 and who was created a prince of Belgium in 1995. Princess Astrid, with her own descendants, is before her brother Laurent in the order of succession to the Belgian throne, due to the 1991 act of succession mentioned above. They have five children:

Other descendants of Leopold III

- HRH Henri, Grand Duke of Luxembourg (born 16 April 1955). He is the eldest son of Grand Duke Jean and Princess Joséphine-Charlotte of Belgium, sister of Kings Baudouin and Albert II and aunt of King Philippe.

- HRH Princess Léa of Belgium (born 2 December 1951). She is the widow of Prince Alexandre of Belgium, half-brother of both Kings Baudouin and Albert II, and half-uncle of King Philippe.

- HRH Princess Marie-Christine, Mrs Gourgues (born 6 February 1951). She is the eldest daughter of Leopold III and Lilian, Princess of Réthy, half-sister of both Kings Baudouin and Albert II and half-aunt of King Philippe. Her first marriage, to Paul Drucker (Toronto, Ontario, 1 November 1937 – 1 April 2008) in Coral Gables, Miami-Dade County, Florida, on 23 May 1981, lasted 40 days (though they weren't formally divorced till 1985); she subsequently married Jean-Paul Gourges in Los Angeles, California, on 28 September 1989.

- HRH Princess Marie-Esméralda, Lady Moncada (born 30 September 1956). She is the youngest daughter of Leopold III and Lilian, Princess of Réthy, half-sister of both Kings Baudouin and Albert II and half-aunt of King Philippe. Princess Marie-Esméralda is a journalist, writing under the name Esméralda de Réthy. She married Sir Salvador Moncada, a Honduran-British pharmacologist, in London on 4 April 1998. They have a daughter, Alexandra Leopoldine (born in London on 4 August 1998), and a son, Leopoldo Daniel (born in London on 21 May 2001).

Family tree of members

Deceased members

.JPG.webp)

- Crown Prince Louis Philippe (eldest son of Leopold I, died in 1834);

- Queen Louise-Marie (second wife of Leopold I, died in 1850);

- King Leopold I (second son of Prince Francis, died in 1865);

- Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico (husband of Princess Charlotte, daughter of Leopold I, died in 1867);

- Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant (eldest son of Leopold II, died in 1869);

- Princess Joséphine-Marie (second daughter of Prince Philippe, third son of Leopold I, died in 1871);

- Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria (first husband of Princess Stéphanie, daughter of Leopold II, died in 1889);

- Prince Baudouin (eldest son of Prince Philippe, third son of Leopold I, died in 1891);

- Queen Marie Henriette (wife of Leopold II, died in 1902);

- Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders (third son of Leopold I, died in 1905);

- King Leopold II (second son of Leopold I, died in 1909);

- Princess Marie, Countess of Flandres (widow of Prince Philippe, third son of Leopold I, died in 1912);

- Prince Karl Anton of Hohenzollern (husband of Princess Joséphine Caroline, sister of Albert I, died in 1919);

- Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke in Saxony (husband of Princess Louise, daughter of Leopold II, died in 1921);

- Princess Louise of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duchess in Saxony (eldest daughter of Leopold II, died in 1924);

- Prince Victor, Prince Napoléon (husband of Princess Clémentine, daughter of Leopold II, died in 1926);

- Empress Carlota of Mexico (eldest daughter of Leopold I, died in 1927);

- Prince Emmanuel, Duke of Vendôme and Alençon (husband of Princess Henriette, sister of Albert I, died in 1931);

- King Albert I (youngest son of Prince Philippe, third son of Leopold I, died in 1934);

- Queen Astrid (first wife of Leopold III, died in 1935);

- Crown Princess Stéphanie of Austria, Princess Lónyai de Nagy-Lónya (eldest daughter of Leopold II, died in 1945);

- Prince Elemér Lónyai de Nagy-Lónya (widower of Princess Stéphanie, daughter of Leopold II, died in 1946);

- Princess Henriette, Duchess of Vendôme and Alençon (eldest daughter of Prince Philippe, third son of Leopold I, died in 1948);

- Clémentine, Princess Napoléon (youngest daughter of Leopold II, died in 1955);

- Princess Joséphine-Caroline of Hohenzollern (third daughter of Prince Philippe, son of Leopold I, died in 1958);

- Queen Elisabeth (widow of Albert I, died in 1965);

- King Umberto II of Italy (husband of Princess Maria-José, daughter of Albert I, died in 1983);

- Prince Regent Charles, Count of Flanders (second son of Albert I, died in 1983);

- King Leopold III (eldest son of Albert I, died in 1983);

- King Baudouin I (eldest son of Leopold III, died in 1993);

- Queen Marie-José of Italy (eldest daughter of Albert I, died in 2001);

- Lilian, Princess of Réthy (second wife of Leopold III, died in 2002);

- Grand Duchess Joséphine-Charlotte of Luxembourg (eldest daughter of Leopold III, died in 2005);

- Prince Alexandre (third son of Leopold III, died in 2009);

- Queen Fabiola (widow of Baudouin I, died in 2014);

- Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg (widower of Princess Joséphine-Charlotte, daughter of Leopold III, died in 2019);

Royal consorts

- Princess Louise d'Orléans (second wife of King Leopold I)

- Archduchess Marie Henriette of Austria (wife of King Leopold II)

- Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria (wife of King Albert I)

- Princess Astrid of Sweden (first wife of King Leopold III)

- Mary Lilian Baels* (second wife of King Leopold III)

- Doña Fabiola de Mora y Aragón (wife of King Baudouin)

- Donna Paola Ruffo di Calabria (wife of King Albert II)

- Jonkvrouwe Mathilde d'Udekem d'Acoz (wife of King Philippe)

See also

- List of Belgian monarchs

- List of heirs to the Belgian throne

- Line of succession to the Belgian throne

- Crown Council of Belgium

- Princess Delphine of Belgium and Royal bastard

References

- "History". Monarchy of Belgium. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "La Constitution Belge" [The Belgian Constitution] (PDF). Belgian Federal Parliament. May 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Arango, Ramon (1961). Leopold III and the Belgian Royal Question. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780801800405.

- Van Kalken, Frans (1950). La Belgique contemporaine (1780-1949) (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. p. 43.

...dirigeant personnellement les Affaires étrangères, comme un souverain d'Ancien Régime, en discutant toutes les questions importantes avec ses ministres, ceux-ci n'ayant d'autorité que pour autant qu'ils étaient ministres du roi...

- Lebrun, Pierre (1981). Essai sur la révolution industrielle en Belgique: 1770-1847 (in French) (Second ed.). Bruxelles: Palais des Académies.

- Forbath, Peter (1977). The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic Rivers. Harper & Row. p. 278. ISBN 978-0061224904.

- Wertham, Frederic (1969). A Sign For Cain: An Exploration of Human Violence. Paperback Library.

- Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0618001903.

King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa.

- "A Belgian Visit to "Kongo"". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Raymond Fusilier, Les monarchies parlementaires en Europe Editions ouvrières, Paris, 1960, p. 399.

- Yvon Gouet, De l'unité du cabinet parlementaire, Dalloz, 1930, p. 232, quoted by Raymond Fusilier, p. 400.

- Leopold III and the Belgian Royal Question, p. 31.

- Yves de Wasseige, Le roi, la loi la liberté: inconciliables en démocratie? in Les faces cachées de la monarchie belge, TOUDI (n° 5/Contradictions (n° 65/66), 1991, ISBN 2-87090-010-4

- Ramon Arango, Leopold III and the Belgian Royal Question, p.9.

- Les monarchies parlementaires en Europe, Editions ouvrières, Paris, 1960, p. 350

- Ramon Arango, p. 9.

- R.Arango, p. 12.

- Hans Daalder, The monarchy in a parliamentary system, in Res Publica, Tijdschrift voor Politologie, Revue de Science Politique, Belgian Journal of Political Science, number 1, 1991, pp. 70–81, p. 74.

- Raymond Fusilier, Les monarchies parlementaires - étude sur les systèmes de gouvernement en Suède, Norvège, Luxembourg, Belgique, Pays-bas, Danemark, Editions ouvrières, Paris, 1960, pp. 419-420.

- Bagehot, The English Constitution

- R.Fusilier, pp. 419–420. French Elle n'est pas purement symbolique, car elle participe à la direction des affaires de l'Etat dans la mesure où sa volonté coïncide avec la volonté des ministres, lesquels seuls assument la responsabilité de la politique du gouvenement.

- French Le Roi règne. Pendant plus d'un siècle et demi (...) on ne s'est guère interrogé sur cette maxime. Ou bien on a cherché à lui donner un sens réducteur. Le Roi préside les Te Deum et les cérémonies protocolaires (...) Régner ne signifie pas suivre d'un oeil distrait les occupations du gouvernement (...) C'est contribuer (...) au fonctionnement harmonieux de l'Etat, in La Libre Belgique (April 1990) quoted by Les faces cachées de la monarchie belge, Contradictions, number 65–66, 1991, p. 27. ISBN 2-87090-010-4

- French Certains étrangers croient - ils le disent souvent - que le maintien de l'unité belge tient à la personne du Roi. Cela est d'une grande naïveté. Il n'est qu'une pièce sur l'échiquier. Mais, sur l'échiquier, le Roi est une pièce qui compte., Jean Stengers, L'action du roi en Belgique depuis 1831, Duculot, Gembloux, 1992, p. 312. ISBN 2-8011-1026-4

- "The Belgian Constitution" (PDF). Belgian Parliament. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Balfoort, Brigitte; et al. "journalist" (PDF). The Belgian Monarchy. Olivier Alsteens, Director-General of the FPS Chancellery of the Prime Minister, Wetstraat 16, 1000 Brussels. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Le Moniteur belge". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Royal Decree of July 12, 2019". Moniteur Belge. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Assistant, Jess IlseEditorial (13 July 2019). "King Philippe and Queen Mathilde visit ancestral castles during visit to German states". Royal Central. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Minutes of the Belgian Senate of September 9, 2004" (in Dutch). The Belgian Senate. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- http://www.gva.be/cnt/dmf20180126_03324113/ze-noemen-ons-sneeuwwitje-en-de-zeven-dwergen

- https://www.rtl.be/people/royautes/voici-la-nouvelle-filleule-de-la-reine-mathilde-photos--909068.aspx

- "No, Argentina's president did not adopt a Jewish child to stop him turning into a werewolf". 29 December 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- "Prince Philippe, Belgium's New King, Still Has Many Hearts to Win". The Huffington Post. 18 July 2013.

- "Walen zijn veel koningsgezinder dan Vlamingen". deredactie.be. 15 November 2016.

- "Arrêté royal relatif à l'octroi du titre de Prince ou Princesse de Belgique" [Royal Decree on the granting of the title of Prince or Princess of Belgium] (in French). Federal Parliament of Belgium. 12 November 2015.

- Clevers, Antoine (25 November 2015). "Le Roi limite l'octroi du titre de "prince de Belgique"" [The King limits the granting of the title of "Prince of Belgium"]. La Libre Belgique. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belgian monarchy. |

- The Belgian monarchy – official site of the Belgian royal family

- The Belgian monarchy - official brochure of the Belgium government

- What role for a Belgian monarch? - website Expatica.com