Hami

Hami is a prefecture-level city in Eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known as the home of sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city was merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city with the county-level city becoming Yizhou District.[1][2] Since the Han dynasty, Hami has been known for its production of agricultural products and raw resources.

Hami

哈密市 قۇمۇل شەھىرى | |

|---|---|

Hami | |

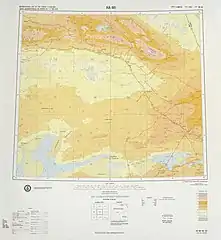

Hami Prefecture (red) in Xinjiang (orange) | |

Hami Location of the city center in Xinjiang | |

| Coordinates (Hami municipal government): 42°49′09″N 93°30′54″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Autonomous region | Xinjiang |

| Municipal seat | Yizhou District |

| Area | |

| • Total | 140,749 km2 (54,343 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 759 m (2,490 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 580,000 |

| • Density | 4.1/km2 (11/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 839000 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-XJ-05 |

| Hami | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 哈密 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | قۇمۇل | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Origins and names

Cumuḍa (sometimes Cimuda or Cunuda) is the oldest known endonym of Hami, when it was founded by a people known in Han Chinese sources as the Xiao Yuezhi ("Lesser Yuezhi"),[3] during the 1st millennium BCE.

The oldest attested Chinese names is "昆莫" (Kūnmò; by the time of the Han dynasty it was referred to in Chinese as "伊吾" (Yīwú) or "伊吾卢" (Yīwúlú), in the Tang dynasty as Yīzhōu, 伊州.[1][2]

By the 10th century CE, the city and its residents were known to the Han as "仲雲" (pinyin: Zhòngyún; Wade–Giles: Chung-yün). A monk named Gao Juhui, who had traveled to the Tarim Basin, wrote that the Zhongyun were descendants of the Xiao Yuezhi and that the king of Zhongyun resided near Lop Nur.[4]

Following the subsequent settlement of Uyghur-speaking people in the area, Cumuḍa became known as Čungul, Xungul, Qumul, Qomul and Kumul (Yengi Yezik̡: K̡umul, K̡omul).

The toponym Yīwúlú also appears as "伊吾廬" in the History of the Yuan dynasty,[5] the biographies of which include references to the place using both names: Baurchuk Art Tekin (巴而朮阿而忒的斤) bases his troops at Hāmìlì in juan 122, while one Tabun (塔本) is recorded as being a man of Yīwúlú in juan 124.[6]

During the Yuan dynasty the Mongolian name for the place, Qamil, transcribed into Chinese as "哈密力" (Hāmìlì), was widely used.[7]

Marco Polo reported visiting "Camul" in the early 14th century and that was the name under which it first appeared on European maps, during the 16th century.

From the Ming dynasty onwards, Qumul was known in Han sources as "哈密" (Hāmì).

When Matteo Ricci visited the city in 1605 in his account of the Portuguese Jesuit Benedict Goës, he used the same spelling as well.[8]

Lionel Giles has recorded the following names (with his Wade–Giles forms of the Chinese names converted to Pinyin):

- Kunwu (Zhou)

- Yiwu or Yiwulu (Han)

- Yiwu Jun (Sui)

- Yi Zhou (Tang)

- Kumul, Kamul, Camul (Turkic)

- Khamil (Mongol)

- Hami (Han Chinese name)

History

Hami is a modern city named after the Chinese name for the wider province, a disputed region claimed by various states throughout history, and its historic capital, Qocho, about 325 km to the west.

During the Later Han dynasty, Hami repeatedly changed hands between the Chinese and Xiongnu who both wanted to control this fertile and strategic oasis. Several times the Han set up military agricultural colonies to feed their troops and supply trade caravans. It was especially noted for its melons, raisins and wine.[9]

- "The region of Yiwu [Hami] is favourable for the five types of grain [rice, two kinds of millet, wheat and beans], mulberry trees, hemp, and grapes. Further north is Liuzhong [Lukchun]. All these places are fertile. This is why the Han have constantly struggled with the Xiongnu over Jushi [Turfan/Jimasa] and Yiwu [Hamich], for the control of the Western Regions."[10]

The decline of the Xiongnu and the Han dynasty led to relative stability and peace for Hami and the surrounding area. However, in 456, the Northern Wei dynasty occupied the Hami region. Based here, they launched raids against the Rouran Khagante. After the decline of the Northern Wei dynasty around the 6th century, the First Turkic Khaganate assumed control of the region. Hami was then tossed around between the western and eastern branches of the khaganate.[11]

Xuanzang visited the oasis town, famous for its melons, the first of a string of oases supplied by the Tian Shan Mountains. This water had been preserved in underground wells and channels since time immemorial. The town had long been inhabited by a Chinese military colony. During the early Tang dynasty and reaching into the Sui dynasty, the Chinese colony had accepted Turkic rule. Xuanzang stayed at a monastery inhabited at the time by three Chinese monks.[12]

The Tang Dynasty asserted control over the region and occupied Hami in the 7th century. The Tibetan Empire and the Tang vied for control of the region until the Chinese were repelled in 851. After the collapse of the Uyghur empire, a group of Uyghurs migrated to the Hami region and ushered in an era of linguistic and cultural change of the local population.[11] The Mongols conquered this region during the Yuan Dynasty. Later Gunashiri, a descendant of Chagatai Khan, founded his own small state called Qara Del in Kumul or Hami, which accepted Ming supremacy in the early 15th century, but was conquered by another branch of Mongols later on.

The Ming Dynasty established this region as Kumul Hami in 1404 after the Mongol kingdom Qara Del accepted its supremacy. But it was later controlled by Oirat Mongols. Hami officially accepted and converted to Islam in 1513.[13] Since the 18th century, Kumul became the center of the Kumul Khanate, a semi-autonomous vassal state within the Qing Empire and the Republic of China as part of Xinjiang. The last ruler of the khanate was Maqsud Shah.

A traveler in 1888 gave the following description of the city:

- ""The kingdom of Ha-mi contains a great number of villages and hamlets; but it has, properly, only one city, which is its capital, and has the same name. It is surrounded by lofty wall, which are half a league in circumference, and has two gates, one of which fronts the east, and the other the west. These gates are exceedingly beautiful, and make a fine appearance at a distance. The streets are straight, and well laid out; but the houses (which contain only a ground-floor, and which are almost all constructed of earth) make very little shew: however, as this city enjoys a serene sky, and is situated in a beautiful plain, watered by a river, and surrounded by mountains which shelter it from the north winds, it is a most agreeable and delightful residence. On whatever side one approaches it, gardens may be seen, which contain everything that a fertile and cultivated soil can produce in the mildest climates. All the surrounding fields are enchanting; but they do not extend far; for on several sides they terminate in dry plains, where a number of beautiful horses are fed, and a species of excellent sheep, which have large flat tails which sometimes weigh three hundred pounds. The country of Ha-mi appears to be very abundant in fossils and valuable minerals: the Chinese have, for a long time, procured diamonds and a great deal of gold from it; at present, it supplies them with a kind of agate, on which they set a great value."[14]

Geography and climate

Hami is located at the border with Gansu province.

Hami (Kumul) is in a fault depression at 759 m (2,490 ft) above sea level, and has a temperate zone, continental desert climate (Köppen BWk) (see Hami Desert), with extreme differences between summer and winter, and dry, sunny weather year-round. On average, there is only 43.6 mm (1.72 in) of precipitation annually, occurring on 25 days of the year. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 68% in December to 79% in September and October, the city receives 3,285 hours of bright sunshine annually, making it one of the sunniest nationally. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −9.8 °C (14.4 °F) in January to 26.8 °C (80.2 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 10.25 °C (50.4 °F). The diurnal temperature variation is typically large, at about an average 15 °C (27 °F) for the year.

| Climate data for Hami (Kumul) (1981−2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.8 (14.4) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −15.5 (4.1) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.4 (0.06) |

1.4 (0.06) |

1.5 (0.06) |

2.9 (0.11) |

4.0 (0.16) |

5.7 (0.22) |

9.0 (0.35) |

5.7 (0.22) |

3.3 (0.13) |

4.0 (0.16) |

2.9 (0.11) |

1.8 (0.07) |

43.6 (1.71) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 24.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 46 | 33 | 28 | 33 | 37 | 43 | 44 | 47 | 51 | 55 | 62 | 45 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 210.4 | 219.9 | 267.9 | 288.3 | 338.8 | 329.6 | 333.4 | 323.3 | 296.9 | 270.6 | 216.5 | 189.5 | 3,285.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 73 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 75 | 72 | 72 | 75 | 79 | 79 | 74 | 68 | 74 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration (precipitation days and sunshine 1971–2000)[15][16] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

| map | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | Hanzi | Hanyu Pinyin | Uyghur (UEY) | Uyghur Latin (ULY) | Population (2010 Census) | Area (km²) | Density (/km²) | |

| 1 | Yizhou District | 伊州区 | Yīzhōu Qū | ئىۋىرغول رايونى | Iwirghol Rayoni | 472,175 | 81,794 | 5.77 | |

| 2 | Yiwu County | 伊吾县 | Yīwú Xiàn | ئارا تۈرۈك ناھىيىسى | Ara Türük Nahiyisi | 24,783 | 19,821 | 1.25 | |

| 3 | Barkol Kazakh Autonomous County | 巴里坤哈萨克自治县 | Bālǐkūn Hāsàkè Zìzhìxiàn | ئاپتونوم ناھىيىسى باركۆل قازاق | Barköl Qazaq Aptonom Nahiyisi | 75,442 | 37,304 | 2.02 | |

Demographics

As of 2017, Hami had a population of about 580,000 of which 68.4% were Han Chinese and 31.6% ethnic minorities, mostly Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Hui.

As of 2015, 427,657 (76.6%) of the 616,711 residents of the county were Han Chinese, 109,072 (17.6%) were Uyghur, 55,550 (9.0%) were Kazakh and 17,588 (2.8%) were Hui.[17]

Economy

The Hami area is known for its large amount of high quality raw resources with 76 kinds of metals already detected. The major mineral resources of this area include coal, iron, copper, nickel, gold.

A newly discovered nickel deposit in Hami is estimated to contain reserves of over 15.8 million tons of the metal, it therefore ranks as China's second largest nickel mine. Around 900,000 tons of nickel has already been detected. Some local copper and nickel mining enterprises are reported to have begun operation, with Xinjiang Nonferrous Metals Group mining company running its nickel smelter crude production furnace at Hami Industrial Park.

Transport

Hami is connected to Xinjiang and the rest of China by both high-speed and conventional rail links. The Lanzhou–Xinjiang High-Speed Railway, a passenger dedicated high speed rail line running 1,776 kilometers (1,104 mi) from Lanzhou in Gansu Province to Ürümqi passes through the city. Hami is a stopping point for the Lanzhou–Xinjiang Railway and Ejin–Hami Railway, two lines that are part of trans-national transport corridors. The Lanzhou–Xinjiang Railway carries passengers and freight, connecting the rest of China to Central Asia and beyond as part of the New Eurasian Land Bridge through a border cross in Kazakhstan, and the Ejin–Hami Railway moves passengers and freight as part of a planned corridor beginning in the Bohai Gulf in North China to Torugart Pass on the border with Kyrgyzstan. A short rail line of 374.83 km (233 mi) transports potassium salts mined near Lop Nur to Hami.

By road Hami is located along China National Highway 312, an east–west route of 4,967 km (3,086 mi) from Shanghai to Khorgas, Xinjiang in the Ili River valley, on the border with Kazakhstan.

Hami Airport is a one-gate airport located 12.5 km (7.8 mi) northeast of the city center.

See also

Footnotes

- E. Bretschneider (1876). Notices of the Mediæval Geography and History of Central and Western Asia. Trübner & Company. pp. 110–.

- Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The Branch. 1876. pp. 184–.

- H. W. Bailey, Indo-Scythian Studies: Being Khotanese Texts, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–7, 16, 101, 133.

- Ouyang Xiu & Xin Wudai Shi, 1974,New Annals of the Five Dynasties, Beijing, Zhonghua Publishing House, p. 918 – cited by: Eurasian History, 2008–09, The Yuezhi and Dunhuang (月氏与敦煌) (18 March 2017).

- Song Lian et al., Yuanshi (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1976), p. 3043.

- Song Lian et al., Yuanshi (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1976), pp. 3001, 3043.

- Song Lian et al., Yuanshi (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1976), p. 3001.

- Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583–1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953). This is an English translation of the Latin work, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas based on Matteo Ricci's journals completed by Nicolas Trigault. Page 513. There is also full Latin text available on Google Books.

- Hill (2009), pp. 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 15, 49, 51, 53, and note 1.6 on pp. 67-69, note 1.26, pp. 111–114.

- Hill (2009), p. 15.

- Schellinger, Paul; Salkin, Robert, eds. (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 5: Asia and Oceania. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 321. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang. Westview Press. pp. 20–21.

- Betta, Chiara (2004). The Other Middle Kingdom: A Brief History of Muslims in China. Indianapolis: University of Indianapolis Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-880938-53-6.

- Grosier (1888), pp. 336-337.

- 中国气象数据网 - WeatherBk Data (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- 3-7 各地、州、市、县(市)分民族人口数 (in Chinese). شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى 新疆维吾尔自治区统计局 Statistic Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

References

- Giles, Lionel (1930–1932). "A Chinese Geographical Text of the Ninth Century." BSOS VI, pp. 825–846.

- Grosier, Abbe (1888). A General Description of China. Translated from the French. G.G.J. and J. Robinson, London.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hami. |

| Look up Hami or Ha-mi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- hmnet.gov.cn Chinese government site on K̡umul (in Chinese)

- hami.gov.cn Chinese government site on K̡umul (in Chinese)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 877.