Hinduism in Pakistan

Hinduism is the second largest religion in Pakistan after Islam.[5] According to the 2017 Pakistan Census, Hindus made up 2.14% of Pakistan's population,[6][7] although the Pakistan Hindu Council claims there are around 8 million Hindus currently living in Pakistan, comprising 4% of the Pakistani population.[2][7] According to Pew Research Center's estimate, Pakistan has the fifth-largest Hindu population in the world in 2010 and by 2050 may rise to the fourth-largest Hindu population in the world.[8][9] However, forced as well as some enticed religious conversions have been bringing down the number of Hindus in Pakistan by upto 1,000 per year.[10][11][12][13]

_During_Yanglaj_Yatra_2017_Photo_by_Aliraza_Khatri.jpg.webp) Hawan at Shri Hinglaj Mata temple during Hinglaj Yatra | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8 million or 4% (Pakistan Hindu Council 2018 claim)[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sindh, Punjab, Khyber Pakthunkhwa, Balochistan | |

| Languages | |

| Sindhi, Thari, Dhatki, Vaghri, Koli, Gujrati and Marwari[4] |

Before partition, according to the 1941 census, Hindus constituted 14% of the population in West Pakistan (now Pakistan) and 28% of the population in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[14][15][16] After Pakistan gained independence from the British Raj, 4.7 million of West Pakistan's Hindus and Sikhs moved to India as refugees.[17] And in the first census afterwards in 1951, Hindus made up 1.6% of the total population of West Pakistan (now Pakistan), and 22% of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[18][19][20]

Hindus in Pakistan are primarily concentrated in Sindh, where the majority of Hindu enclaves are found in Pakistan.[21] They speak a variety of languages such as Sindhi, Seraiki, Aer, Dhatki, Gera, Goaria, Gurgula, Jandavra, Kabutra, Koli, Loarki, Marwari, Sansi, Vaghri,[22] and Gujarati.[23] Although small in numbers, Hindus in Pakistan are not less complex than in other parts of the world. Many Hindus, especially in the rural areas, follow the teachings of local Sufi pīrs (Urdu: spiritual guide) or adhere to the 14th-century saint Ramdevji, whose main temple Shri Ramdev Pir temple is located in Tando Allahyar. A growing number of urban Hindu youth in Pakistan associate themselves with ISKCON society. Other communities worship manifold "Mother Goddesses" as their clan or family patrons. A different branch, the Nanakpanth, follows the teachings of the Guru Granth Sahib, also known as the holy book of the Sikhs. This diversity, especially in rural Sindh, often thwarts classical definitions between Hinduism, Sikhism and Islam.

One of the most important places of worship for Hindus in Pakistan is the shrine of Shri Hinglaj Mata temple in Balochistan.[24][25] The annual Hinglaj Yatra is the largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan.[26]

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

History

Ancient ages

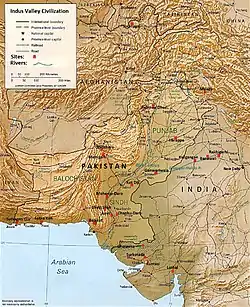

The Rig Veda, the oldest Hindu text, is believed to have been composed in the Punjab region of modern-day Pakistan (and India) on the banks of the Indus River around 1500 BCE.[27] Various archaeological finds such as the Swastika symbol, Yogic postures, what appears to be like a "Pasupati" image that was found on the seals of the people of Mohenjo-daro, in Sindh, point to early influences that may have shaped Hinduism. The religious beliefs and folklore of the Indus valley people have become a major part of the Hindu faith that evolved in this part of the South Asia.[28]

The Sindh kingdom and its rulers play an important role in the Indian epic story of the Mahabharata. In addition, a Hindu legend states that the Pakistani city of Lahore was first founded by Lava, while Kasur was founded by his twin Kusha, both of whom were the sons of Lord Rama of the Ramayana. The Gandhara kingdom of the northwest, and the legendary Gandhara people, are also a major part of Hindu literature such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Many Pakistani city names (such as Peshawar and Multan) have Sanskrit roots.[29][30]

During Independence

.jpg.webp)

At the time of Pakistan's creation the 'two nation theory' had been espoused. According to this theory the Hindu minority in Pakistan was to be given a fair deal in Pakistan in order to ensure the protection of the Muslim minority in India.[31][32] However, Khawaja Nazimuddin, the 2nd Prime Minister of Pakistan stated: "I do not agree that religion is a private affair of the individual nor do I agree that in an Islamic state every citizen has identical rights, no matter what his caste, creed or faith be".[33]

After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, over 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs from West Pakistan left for India, and 6.5 million Muslims chose to migrate to Pakistan.[17] The reasons for this exodus were the heavily charged communal atmosphere in British Raj, deep distrust of each other, the brutality of violent mobs and the antagonism between the religious communities. That over 1 million people lost their lives in the bloody violence of 1947 should attest to the fear and hate that filled the hearts of millions of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs who left ancestral homes hastily after independence.

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1,276,116 | — |

| 1990 | 1,723,251 | +35.0% |

| 1998 | 2,443,614 | +41.8% |

| 2017 | 4,444,437 | +81.9% |

| Hindus were separated as Hindu( jati) and Hindu Scheduled Castes from 1998 Census Source: [34][35][6] | ||

Hinduism (%) in Pakistan by decades[36][37][35][6]

| Year | Percent | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 14% | - |

| 1947 | 12.9% |

-1.1% |

| 1951 | 1.3% |

-11.8% |

| 1981 | 1.5% |

+0.2% |

| 1998 | 1.85% |

+0.35% |

| 2017 | 2.14% |

+0.29% |

Before partition, according to the 1941 census, Hindus constituted 14% of the population in West Pakistan (currently Pakistan) and 28% of the population in East Pakistan(currently Bangladesh).[38][39] In 1947, Hindus constituted 12.9% of Pakistan, which made Pakistan (including present day Bangladesh) the second-largest Hindu-population country after India.[40]After Pakistan gained independence from Britain on 14 August 1947, 4.7 million of the country's Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India.[17] In the 1951 census, West Pakistan (now Pakistan) had 1.3% Hindu population, while East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) had 22.05%.[41][42][43] After 1971, Bangladesh separated from Pakistan and the population of Hindus and other Non-Muslims declined in Pakistan as Bangladesh population was no longer part of the census conducted in Pakistan.[18] The 1998 census of Pakistan recorded 2,443,614 Hindus, which (includes 332,343 scheduled caste Hindus), which constitutes to 1.85 percentage of the total population of Pakistan.[35][5] and about 7.5% in the Sindh province.

In 1956, the government of Pakistan declared 32 castes and tribes, the majority of them Hindus, to be scheduled castes, including Kohlis, Meghawars, and Bheels.[44][45] The Pakistan Census separates the members of scheduled castes from Hindus and has assessed that they form 0.25% of the national population.[35][40] However, the actual population of Scheduled Caste Hindus is expected to be much higher, as the Scheduled Caste Hindus categorise themselves as Hindus in the census rather than as Scheduled Castes.[46]

As per the data from the Election Commission of Pakistan, as of 2018 there were a total of 1.77 million Hindu voters. Hindu voters were 49% of the total in Umerkot and 46% in Tharparkar.[47][48] According to estimates in religious minorities in Pakistan's elections, the Hindus have a population of 50,000 or more in 11 districts. All of these are in Sindh except the Rahim Yar Khan District in Punjab.[49]

Hindu population by province

The percent of population of Hindus (separating the scheduled castes from other Hindus) in the provinces in Pakistan, according to the 1998 census:[5][35]

| Province | Total Population | Hindu (Jati) | Scheduled Castes | All Hindus | Percentage of the total number of Hindus in Pakistan | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30,439,893 | 1,980,534 | 6.51% | 300,308 | 0.99% | 2,280,842 | 7.49% | 93.34% | |

| 6,565,885 | 32,387 | 0.49% | 6,759 | 0.10% | 39,146 | 0.60% | 1.60% | |

| 73,621,290 | 92,628 | 0.13% | 23,782 | 0.03% | 116,410 | 0.16% | 4.76% | |

| 17,743,645 | 4,498 | 0.025% | 592 | 0.003% | 5,090 | 0.029% | 0.21% | |

(merged with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018) |

3,176,331 | 1,046 | 0.03% | 875 | 0.03% | 1,921 | 0.06% | 0.08% |

| 805,235 | 178 | 0.022% | 27 | 0.003% | 205 | 0.025% | 0.008% | |

| Pakistan (total) | 132,352,279 | 2,111,271 | 1.60% | 332,343 | 0.25% | 2,443,614 | 1.85% | 100.00% |

Hindu population by district

All districts with a Hindu population greater than 2%, according to the 1998 census. In other districts the population of Hindus is less than 1%.

| Administrative Unit | District | Percentage of Hindus |

|---|---|---|

| Sindh | Umerkot | 47.6% |

| Tharparkar | 40.5% | |

| Mirpurkhas | 32.7% | |

| Sanghar | 20% | |

| Badin | 19.9% | |

| Hyderabad | 12% | |

| Ghotki | 6.7% | |

| Jacobabad | 3.5% | |

| Sukkur | 3% | |

| Khairpur | 2.9% | |

| Nawabshah | 2.8% | |

| Thatta | 2.8% | |

| Dadu | 2% | |

| Punjab | Rahim Yar Khan | 2.3% |

In other districts the population of Hindus is less than 1%.

Religious, social and political institutions

The Pakistan Hindu Panchayat, Pakistan Hindu Council and the Pakistani Hindu Welfare Association are the primary civic organizations that represent and organise Hindu communities on social, economic, religious and political issues in most of the country, with the exception of the Shiv Temple Society of Hazara, which especially represents community interests in the Hazara region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in addition to being the special guardians of the Shiva temple, at Chitti Gatti village, near Mansehra. The Pakistan Hindu Council runs 13 schools across Tharparkar[50] and also conducts mass wedding of poor Hindu couples.[51]

ISKCON also has a presence in Pakistan. It is involved in preaching and distributing Urdu translated Bhagavad Gita. It has a large following among the Scheduled Caste Hindus in Urban areas of Pakistan. There is a significant increase in the influence of Iskcon due to its rejection of caste system.[52]

There was a Ministry of Minority Affairs in the Government of Pakistan which looked after specific issues concerning Pakistani religious minorities. In 2011, the Government of Pakistan closed the Ministry of Minority Affairs.[53][54] And a new ministry Ministry for National Harmony was formed for the protection of the rights of the minorities in Pakistan.[55] But in 2013, the Ministry of National Harmony was merged with the Ministry of Religious Affairs despite opposition from the minorities.[56]

Politics

The Constitution's Article 51(2A) provides 10 reserved seats for non-Muslims in the National Assembly, 23 reserved seats for non-Muslims in the four provincial assemblies under Article 106[57] and four seats for non-Muslims in the Senate of Pakistan.[49] Conventionally, Hindus were allotted 4 or 5 seats. The number of national Assembly seats were increased from 207 in 1997 to 332 in 2002. But the number of non-Muslim reserved seats were not increased from 10. Similarly, the number of seats in Provincial Assembly of Sindh and Punjab were increased from 100 to 159 and 240 to 363 respectively, but the non-Muslim reserved seats were not increased.[45] Although a bill for increasing minorities' seats was introduced by Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, it was not passed.[58] Political parties Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) party is against giving reserved seats for minorities.[59]

In 1980s Zia ul-Haq introduced a system under which non-Muslims could vote for only candidates of their own religion. Seats were reserved for minorities in the national and provincial assemblies. Government officials stated that the separate electorates system is a form of affirmative action designed to ensure minority representation, and that efforts are underway to achieve a consensus among religious minorities on this issue, but critics argued that under this system Muslim candidates no longer had any incentive to pay attention to the minorities. Hindu community leader Sudham Chand protested against the system but was murdered. In 1999, Pakistan abolished this system. Hindus and other minorities achieved a rare political victory in 2002 with the removal of separate electorates for Muslims and non-Muslims. The separate electorate system had marginalized non-Muslims by depriving them of adequate representation in the assemblies. The Pakistan Hindu Welfare Association was active by convening a national conference on the issue in December 2000. And in 2001, Hindus, Christians, and Ahmadis successfully conducted a partial boycott of the elections, culminating in the abolishment of the separate electorate system in 2002. This allowed religious minorities to vote for mainstream seats in the National and Provincial assemblies, rather than being confined to voting for only minority seats. Despite the victory, however, Hindus still remain largely disenfranchised.[60]

In 2006, Ratna Bhagwandas Chawla became the first Hindu woman elected to the Senate of Pakistan.[61] Although there is reservation of seats for women in Pakistan National Assembly, not a single seat was allotted for non-Muslim women till 2018. In 2018, Krishna Kumari Kohli, a Hindu woman became the first non-Muslim woman to win a women's reserved seat in Senate of Pakistan.[62]

In 2018, Pakistan general election Mahesh Kumar Malani became the first Hindu candidate who won a general seat in Pakistan National Assembly 2018. He won the seat from Tharparkar-II and thus became the first non-Muslim to win a general seat (non-reserved) in Pakistan national assembly.[63] In the Sindh provincial assembly election which took place along with the Pakistan National Assembly election 2018, Hari Ram Kishori Lal and Giyan Chand Essrani were elected from the Sindh provincial assembly seats. They became the first non-Muslims to win a general seat (non-reserved) in a provincial assembly election.[64]

Hindu communities

Tamil Hindus

Some Tamil Hindu families migrated to Pakistan in the early 20th century, when Karachi was developed during the British Raj, and were later joined by Sri Lankan Tamils who arrived during the Sri Lankan Civil War. The Madrasi Para area is home to around 100 Tamil Hindu families. The Maripata Mariamman Temple, which has been demolished, was the biggest Tamil Hindu temple in Karachi.[65] The Drigh Road and Korangi also have a small Tamil Hindu population[66]

Kalasha people

The Kalasha people practice an ancient form of Hinduism mixed with animism.[67][68] They are considered as a separate ethnic religion people by the government of Pakistan.[69] They reside in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province.

Nanakpanthi

Nanakpanthi are Hindus who revere Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism along with Hindu gods. Today, a large fraction of Sindhi Hindus consider themselves Nanakpanthi.[70]

Valmiki Hindus

The Valmiki or Balmikis are Hindu worshippers of Valmiki, the author of The Ramayana. Most Valmiki Hindus converted to either Christianity or Islam after the partition. However, many of those who converted still worship Valmiki and celebrate Valmiki Jayanti.[71][72]

Punjabi Hindus

There is a small population of Punjabi Hindus living in the Punjab province of Pakistan, most notably in Lahore where there are some 200 Hindu families.[73][74]

Community life

According to a study, the majority of the scheduled caste Hindus (79%) in Pakistan have experienced discrimination. The discrimination is higher in Southern Punjab (86.5%) compared to the rest of the country. The study found that majority (91.5% ) of the respondents in Rahimyar Khan, Bahawalpur, Tharparkar and Umerkot districts believed that political parties are not giving importance to them. The study also found that the scheduled caste Hindu women are most vulnerable to sexual abuse by Muslim men and young girls are lured into matrimony or abducted and wed through forced conversions.[76][45]

In Balochistan province, Hindus are relatively more secure and face less religious persecution. The tribal chiefs in Balochistan, particularly the Jams of Lasbela and Bugti of Dera Bugti, consider non-Muslims like Hindus as members of their own extended family and allows religious freedom. They have never forced Hindus to convert. Also, in Balochistan Hindu places of worship are proportionate to their population. For example, between Uthal and Bela jurisdiction in Lasbela District, there are 18 temples for 5,000 Hindus living in the area, which is an indicator of religious freedom.[77] However, in Khuzdar District and Kalat District, Hindus face discrimination.[78]

In Peshawar, capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Hindus enjoy religious freedom and live peacefully alongside the Muslims. The city of Peshawar today is home to four Hindu tribes– the Balmiks, the Rajputs, the Heer Ratan Raths and the Bhai Joga Singh Gurdwara community. Since partition, the four tribes have lived in harmony with all religious communities including Muslims. However, there is the lack of upkeep of the dilapidated Hindu temples in the city. The local government always fails to assign caretakers and priests at temples.[79] But in other parts of Kyber Pakhtunkhwa like Buner, Swat and Aurakzai Agencies, Hindu and Sikh families, have been targeted by Taliban for failing to pay Jizya (religious tax) and due to this more than 150 Sikhs and Hindu families in Pakistan's have moved to Hasan Abdal and Rawalpindi in Punjab in 2009[80]

In central Punjab, Hindus are a small minority. After the partition, Hindus have been converting to Islam under pressure, particularly in Doda village near Sargodha. Due to the low population of Hindus in the Central Punjab, many of the Hindus have married Sikhs and vice versa. Intermarriages between the Hindus and Sikhs are very common there.[78]

The Indus river is a holy river to many Hindus, and the Government of Pakistan periodically allows small groups of Hindus from India to make pilgrimage and take part in festivities in Sindh[81] and Punjab.[82] Rich Pakistani Hindus go to India and release their loved ones' remains into the Ganges. Those who cannot afford the trip go to Churrio Jabal Durga Mata temple in Nagarparkar.[83]

Education

According to the Pakistan’s National Council for Justice and Peace (NCJP) report the average literacy rate among Hindu (upper caste) is 34 percent, Hindu (scheduled castes) is 19 percent compared to the national average of 46.56 percent.[84] According to a 2013 survey conducted by the Pakistan Hindu Seva welfare Trust, the literacy rate among scheduled caste Hindus in Pakistan is just 16%. The survey noted that majority of the scheduled caste Hindu families doesn't send their girl children to schools due to the fear of forced conversion.[85]

Hindu marriage acts

There are two laws governing Hindu marriages-Sindh Hindu Marriage act of 2016 ( applicable only in the Sindh province), Hindu marriage act of 2017 ( applicable in Islamabad Capital Territory, Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces). However, there are no laws and amendments made to register a marriage between two Hindus- one from Sindh and another from a different Province( Islamabad Capital Territory, Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab).[86]

The Sindh Hindu Marriage Bill was passed by the Provincial Assembly of Sindh in February 2016. This was the first Hindu Marriage act in Pakistan.[87][88][89]It was amended in 2018 to include divorce rights, remarriage rights and financial security of the wife and children after divorce.[90]

At federal level,a Hindu Marriage Bill was proposed in 2016, which was unanimously approved by the National Assembly of Pakistan in 2016[91][92] and by the Senate of Pakistan in 2017.[93] In March 2017, the Pakistani President Mamnoon Hussain signed the Hindu Marriage Bill and thereby making it a law. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also mentioned that the marriage registrars will be established in areas where Hindus stay.[94]

However, many have criticised the Clause 12(iii) of the Hindu Marriage Bill which says that "a marriage will be annulled if any of the spouses converts to another religion". There are fears the clause would be misused for forced conversions of married women the same way young girls are being subjected to forced conversions.[88]

Temples

The Communal violence of the 1940s and the subsequent persecutions have resulted in the destruction of many Hindu temples in Pakistan, although the Hindu community and the Government of Pakistan have preserved and protected many prominent ones. Some ancient Hindu temples in Pakistan draw devotees from across faiths including Muslims.[96]

According to a survey, there were 428 Hindu temples in Pakistan at the time of Partition and 408 of them were now turned into toy stores, restaurants, government offices and schools.[97] Among these 11 temples are in Sindh, four in Punjab, three in Balochistan and two in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, in November 2019, government of Pakistan started the restoration process for 400 Hindu temples in Pakistan. After restoration, the temples will be reopened to Hindus in Pakistan.[97]

The Pamwal Das Shiv Mandir, centuries-old historic temple in Baghdadi area of Lyari Town was illegally turned into a Muslim Pir and slaughterhouse for cows by Muslim clerics with the help of Baghdadi police after making series of attacks on Hindu families living in the area.[98][99][100]

The 135,000 acres of temple land is now controlled by the Evacuee Trust Property Board. The historic Kali Bari Hindu Temple has been rented out to a Muslim party in Dera Ismail Khan who converted the temple into a Hotel. The Holy Shiv Temple in Kohat has been converted into a government primary school. The Raam Kunde Complex of Temples at Saidpur village in Islamabad is now a picnic site. Another temple at Rawal Dam in Islamabad has been shut down and the Hindu community believes that the temple is going to dilapidate day by day without being handed over to them. In Punjab, a Hindu temple at Rawalpindi was destroyed and reconstructed to use as a community centre, while in Chakwal the Bhuwan temple complex is being used by the local Muslim community for commercial purposes.[101]

Reopened temples

The Goraknath Temple which was closed in the 1947 was reopened in 2011 after a court ruling which ordered the Evacuee Trust Property Board to open it.[102] In 2019, the Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan said that his government will reclaim and restore 400 temples to Hindus.[103] Following this, the 1,000-Year-Old Shivala Teja Singh temple in Sialkot (which was closed for 72 years)[104] and a 100-year-old Hindu temple in Balochistan was reopened.[105]

Important pilgrimage centres in Pakistan

- Shri Hinglaj Mata temple – one of the two Shakti peetha in Pakistan.[106] The annual Hinglaj Yatra is the largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan. More than 250,000 people take part in the Hinglaj Yathra during the spring.[107]

- Shri Ramdev Pir temple in Tando Allahyar District, in Sindh. The annual Ramdevpir mela in the temple is the second largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan.[108]

- Umarkot Shiv Mandir –The three-day Shivrathri festival in the temple is famous. It is one the biggest religious festivals in the country. It is attended by around 250,000 people. All the expenses were borne by the Pakistan Hindu Panchayat.[109]

- Churrio Jabal Durga Mata Temple – Famous for Shivrathri celebrations which is attended by 200,000 pilgrims. Hindus cremate the dead and ashes are preserved till Shivratri for immersion in the into holy water in Churrio Jabal Durga Mata Temple.[83]

- In Peshawar, Dargah Pir Ratan Nath Jee and the Kalibari Mandir, Peshawar are the two functional temples where worshipping is still done. In 2011,

the Goraknath Temple was reopened after a court ruling which ordered the Evacuee Trust Property Board to open it.[102][110][111][112]

Temple desecration

In 2014, a Hindu temple and a dharmashala in Larkana district in Sindh was attacked by a crowd of Muslims.[113] In 2019, three Hindu temples were vandalised in Ghotki district in Sindh over blasphemy accusations.[114]

In January 2020, a Hindu temple in Chachro, Tharparkar district in Sindh was vandalised by miscreants, who desecrated the idols and set fire to holy scriptures.[115]

In December 2020, a Hindu temple in Teri village of Karak district was attacked and vandalised.[116]

Conversions

Each year, 1000 Pakistani girls of minority religions, hindus in particular, are forcibly converted to Islam. The girls are usually kidnapped by complicit acquaintances and relatives or men looking for brides. Sometimes they are taken by powerful landlords as payment for outstanding debts by their farmhand parents, and the authorities often look the other way. [117] In one case, a landlord abducted a hindu daughter from a farm worker and falsely claimed the teen was compensation for a 1,000$ debt that the family owed him. [118] According to the Pakistan Hindu Council, forced conversions remain the foremost reason for the declining population of Hindus in Pakistan. Religious institutions and persons like Abdul Haq (Mitthu Mian) politician and caretaker of Bharachundi Sharif Dargah in Ghotki district and Pir Ayub Jan Sirhindi, the caretaker of Dargah pir sarhandi in Umerkot District support forced conversions and are known to have support and protection of ruling political parties of Sindh.[119][120][121] According to the National Commission of Justice and Peace and the Pakistan Hindu Council (PHC) around 1000 non-Muslim minority women are converted to Islam and then forcibly married off. This practice is being reported increasingly in the districts of Tharparkar, Umerkot and Mirpur Khas in Sindh.[120] According to the Amarnath Motumal, the vice chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, every month, an estimated 20 or more Hindu girls are abducted and converted, although exact figures are impossible to gather.[10] In 2014 alone, 265 legal cases of forced conversion were reported mostly involving Hindu girls.[122]

In November 2016, a bill against forced conversion was passed unanimously by the Sindh Provisional Assembly. However, the bill failed to make it into law as the Governor returned the bill. The Bill was effectively blocked by the Islamist groups and parties like the Council of Islamic Ideology and Jamaat-e-Islami.[123]

In 2019, a bill against forced conversion was proposed by Hindu politicians in the Sindh assembly, but was turned down by the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party lawmakers.[124]

There are also Irish Christian missionaries and Ahmadiyya missionaries operating in the Thar region. The Christian and Ahmadi missionaries offer impoverished Hindus schools, health clinics etc. as an inducement for those who convert.[21] Korean Christian missionaries are also very active in Sindh, who have built schools from Badin to Tharparkar. Korean Christian missionaries have allegedly converted more than 1,000 Hindu families in 2012 alone. According to the Sono Kangharani, member of Pakistan Dalit Network, the Korean missionaries have been active in the area from 2011 and these missionaries don't focus on individuals but they convert entire villages. According to him about 200 to 250 Hindu villages were converted in the last two and a half years between 2014 and 2016.[119]

Decline and persecution

Decline

There has been historical decline of Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism in the areas of Pakistan. This happened for a variety of reasons even as these religions have continued to flourish beyond the eastern frontiers of Pakistan. The region became predominantly Muslim during the rule of Delhi Sultanate and later Mughal Empire. In general, religious conversion was a gradual process, some converted to Islam to gain tax relief, land grant, marriage partners, social and economic advancement,[125] or freedom from slavery and some by force.[126] The predominantly Muslim population supported Muslim League and Partition of India. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the minority Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India while the Muslims refugees from India migrated to Pakistan. Approximately 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs moved to India while 6.5 million Muslims settled in Pakistan.

Some Hindus in Pakistan feel that they are treated as second-class citizens and many have continued to migrate to India.[127][128] According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan data, around 1,000 Hindu families fled to India in 2013.[129] In May 2014, a member of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), Dr Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, revealed in the National Assembly of Pakistan that around 5,000 Hindus are migrating from Pakistan to India every year.[130]

Those Pakistani Hindus who have migrated to India allege that Hindu girls are sexually harassed in Pakistani schools and their religious practices are mocked.[131] The Indian government is planning to issue Aadhaar cards and PAN cards to Pakistani Hindu refugees, and simplifying the process by which they can acquire Indian citizenship.[132]

Many Hindus are induced to convert to Islam for easily getting Watan Cards and National Identification Cards. These converts were also given land and money. For example, 428 poor Hindus in Matli were converted between 2009–11 by the Madrassa Baitul Islam, a Deobandi seminary in Matli, which pays off the debts of Hindus converting to Islam.[133] Another example is the conversion of 250 Hindus to Islam in Chohar Jamali area in Thatta.[134] Conversions are also carried out by Baba Deen Mohammad Shaikh mission which converted 108,000 people to Islam since 1989.[135]

Discrimination

Separate electorates for Hindus and Christians were established in 1985—a policy originally proposed by Islamist leader Abul A'la Maududi. Christian and Hindu leaders complained that they felt excluded from the county's political process, but the policy had strong support from Islamists.[136] Until 1999, when former military chief Pervez Musharaf overthrew Nawaz Sharif's government, non-Muslims had dual voting rights in the general elections that allowed them to not only vote for Muslim candidates on general seats, but also for their own non-Muslim candidates.[137]

The Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA), a coalition of Islamist political parties in Pakistan, calls for the increased Islamization of the government and society, specifically taking an anti-Hindu stance. The MMA leads the opposition in the national assembly, held a majority in the NWFP Provincial Assembly, and was part of the ruling coalition in Balochistan. However, some members of the MMA made efforts to eliminate their rhetoric against Hindus.[138]

In the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition, widespread violence erupted against Hindus. Mobs attacked scores of Hindu temples across Pakistan.[139][140] Shops owned by Hindus were also attacked in Sukkur, Sindh. Hindu homes and temples were also attacked in Quetta.[141]

The rise of Taliban insurgency in Pakistan has been an influential and increasing factor in the persecution of and non-Muslims in Pakistan[142][143][138] In July 2010, around 60 members of the minority Hindu community in Karachi were attacked and evicted from their homes following an incident of a Dalit Hindu youth drinking water from a tap near an Islamic Mosque.[144][145] Between 2011 and 2012, twenty three Hindus were kidnapped for ransom and 13 Hindus were killed as a part of targeted killings of non-Muslims[119] In January 2014, a policeman standing guard outside a Hindu temple at Peshawar was gunned down.[146] Pakistan's Supreme Court has sought a report from the government on its efforts to ensure access for the minority Hindu community to temples – the Karachi bench of the apex court was hearing applications against the alleged denial of access to the members of the minority community.[147][148][149]

Pakistan Studies curriculum issues

According to the Sustainable Development Policy Institute report, "Associated with the insistence on the Ideology of Pakistan has been an essential component of hate against India and the Hindus. For the upholders of the Ideology of Pakistan, the existence of Pakistan is defined only in relation to Hindus, and hence the Hindus have to be painted as negatively as possible".[150]

A 2005 report by the National Commission for Justice and Peace, a non-profit organization, found that Pakistan Studies textbooks in Pakistan have been used to articulate the hatred that Pakistani policy-makers have attempted to inculcate towards the Hindus. "From the government-issued textbooks, students are taught that Hindus are backward and superstitious", the report stated.[151][152][153][154]

In 1975, Islamiat or Islamic studies was made compulsory, resulting that a large number of minority students being forced to study Islamic Studies.[155] In 2015,Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government introduced Ethics as an alternative subject to Islamiat for non-Muslim schoolchildren in the province[156] followed by Sindh in 2016.[155]

Prominent Pakistani Hindus

- Danish Kaneria, Cricketer

- Anil Dalpat, Cricketer[157]

- Deepak Perwani, famous fashion designer

- Rana Bhagwandas, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan

- Naveen Perwani, asian Games bronze medal winner and Sindh Snooker Cup winner[158]

- Ramesh Kumar Vankwani -politician and founder of Pakistan Hindu Council[159]

- Mahesh Kumar Malani – First Hindu to win a general seat in the National Assembly of Pakistan[63]

- Suman Bodani, the first Hindu woman to be appointed civil judge in Pakistan.[160]

- Pushpa Kumari Kohli is the first Hindu woman to become a police officer in Pakistan. [161]

- Veeru Kohli, Human rights activist.[162]

Pre independence

- Indian Prime Ministers-I K Gujral and Gulzarilal Nanda

- Lal Krishna Advani – former deputy prime minister

- Bollywood film stars and directors -Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor, Ramesh Sippy, Vinod Khanna, Manoj Kumar, Yash Chopra, Balraj Sahni, Rajendra Kumar and Sunil Dutt, trace their birthplaces and ancestral homes to the towns of Pakistan.

- Lala Amarnath – Independent India's first Test cricket captain

See also

References

https://www.hafsite.org/human-rights-issues/discrimination-and-persecution-plight-hindus-pakistan

- "Hindu Population (PK)". Pakistan Hindu Council. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- "Hindus of Pakistan reject CAA, do not want Indian Prime Minister Modi's offer of citizenship". Gulf News. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "India's citizenship law divisive: Pakistani Hindus". Anadolu Agency. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Aqeel, Asif (2020). The Index of Religious Diversity and Inclusion in Pakistan (PDF). Lahore: Center for Law and Justice. p. 40.

- "Population Distribution by Religion, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Riazul Haq and Shahbaz Rana (27 May 2018). "Headcount finalised sans third-party audit". Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Hindu Population (PK) – Pakistan Hindu Council". Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "10 Countries With the Largest Hindu Populations, 2010 and 2050". Pew Research Center. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Projected Population Change in Countries With Largest Hindu Populations in 2010". Pew Research Center. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Javaid, Maham (18 August 2014), "Forced conversions torment Pakistan's Hindus", Al Jazeera, retrieved 20 January 2019,

According to a report from the Movement for Solidarity and Peace, about 1,000 non-Muslim girls are converted to Islam each year in Pakistan. Every month, an estimated 20 or more Hindu girls are abducted and converted, although exact figures are impossible to gather, said Amarnath Motumal, the vice chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP).

- Sarfraz, Mehmal (13 April 2019). "In Pakistan, the problem of forced conversions". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Husain, Shahid (15 July 2015). "1,000 girls forcibly converted to Islam in Pakistan every year". The News International. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Abi-Habib, Maria; ur-Rehman, Zia (5 August 2020). "Poor and Desperate, Pakistani Hindus accept Islam to get by". NY Times. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Ranganathan, Anand. "The Vanishing Hindus of Pakistan – a Demographic Study". Newslaundry. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Company, Bobbs-Merrill. The Bobbs-Merrill Reprint Series in Geography. Ardent Media.

- Hill, Kenneth H.; Seltzer, William; Leaning, Jennifer; Malik, Saira J.; Russell, Sharon Stanton; Makinson, C (2004), A Demographic Case Study of Forced Migration: The 1947 Partition of India

"Session 44: Understanding the Forced Migration of Trafficked Persons and Refugees", Population Association of America 2004 Annual Meeting Program - Hasan, Arif; Raza, Mansoor (2009). Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan. IIED. p. 12. ISBN 9781843697343.

When the British Indian Empire was partitioned in 1847, 4.7 million Sikhs and Hindus left what is today Pakistan for India, and 6.5 million Muslims left India and moved to Pakistan.

- Rawat, Mukesh (12 December 2019). "No, Pakistan's non-Muslim population didn't decline". India Today.

- Chakraborty, Chandrima (2 October 2017). Mapping South Asian Masculinities: Men and Political Crises. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-49462-1.

Most of the Hindu population was in East Pakistan, where they constituted 22% of the population in 1951 and 18.4% in 1961. In West Pakistan, they represented only 1.6% (1951 and 1961) of the population.

- Humayun, Syed (1995). Sheikh Mujib's 6-point Formula: An Analytical Study of the Breakup of Pakistan. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-969-407-176-3.

Interestingly, the Hindus, who were the single largest minority, constituted 22% of East Wing population and only 1.6% of West Pakistan

- Ali, Naziha Syed (17 August 2017), "The truth about forced conversions in Thar", Dawn, retrieved 20 January 2019

- "Pakistan". Ethnologue.

- Rehman, Zia Ur (18 August 2015). "With a handful of subbers, two newspapers barely keeping Gujarati alive in Karachi". The News International. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

In Pakistan, the majority of Gujarati-speaking communities are in Karachi including Dawoodi Bohras, Ismaili Khojas, Memons, Kathiawaris, Katchhis, Parsis (Zoroastrians) and Hindus, said Gul Hasan Kalmati, a researcher who authored "Karachi, Sindh Jee Marvi", a book discussing the city and its indigenous communities. Although there are no official statistics available, community leaders claim that there are three million Gujarati-speakers in Karachi – roughly around 15 percent of the city’s entire population.

- Schaflechner, Jürgen (2018). Hinglaj Devi : identity, change, and solidification at a Hindu temple in Pakistan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190850555. OCLC 1008771979.

- Being in the World Productions, ON BECOMING GODS (Pakistan 2011, 44min), retrieved 7 August 2018

- "In a Muslim-majority country, a Hindu goddess lives on". Culture & History. 10 January 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Rigveda | Hindu literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "PLATES", Crowsnest Pass Archaeological Project, Canadian Museum of History, 1974, pp. 59–67, doi:10.2307/j.ctv16t17.17, ISBN 978-1-77282-019-5

- Jarred Scarboro. Ultimate Handbook Guide to Multan : (Pakistan) Travel Guide. p. 7.

- Kumkum Roy. Historical Dictionary of Ancient India. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 259.

- Zamindar, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali (2010). The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories. Columbia University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780231138475.

The logic of the hostage theory tied the treatment of Muslim minorities in India to the treatment meted out to Hindus in Pakistan.

- Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781316258385.

Within the subcontinent, ML propaganda claimed that besides liberating the 'majority provinces' Muslims it would guarantee protection for Muslims who would be left behind in Hindu India. In this regard, it repeatedly stressed the hostage population theory that held that 'hostage' Hindu and Sikh minorities inside Pakistan would guarantee Hindu India's good behaviour towards its own Muslim minority.

- Qasmi, Ali Usman (2015). The Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan. Anthem Press. p. 149. ISBN 9781783084258.

Nazim-ud-Din favored an Islamic state not just out of political expediency but also because of his deep religious belief in its efficacy and practicality...Nazim-ud-Din commented:'I do not agree that religion is a private affair of the individual nor do I agree that in an Islamic state every citizen has identical rights, no matter what his caste, creed or faith be'.

- Dr Iftikhar H. Malik. "Religious Minorities in Pakistan" (PDF). Retrieved 12 February 2020.

-

"Population by Religion" (PDF), Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2003

"Population by religion". Population Census Organization, Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014.

"Population by Religion" (PDF), Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, retrieved 13 June 2020

Also reproduced at scribd.com - https://m.timesofindia.com/india/has-paks-hindu-population-dropped-sharply/articleshow/72686351.cms

- Dr Iftikhar H. Malik. "Religious Minorities in Pakistan" (PDF). Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Company, Bobbs-Merrill. The Bobbs-Merrill Reprint Series in Geography. Ardent Media.

- Hill, Kenneth H.; Seltzer, William; Leaning, Jennifer; Malik, Saira J.; Russell, Sharon Stanton; Makinson, C (2004), A Demographic Case Study of Forced Migration: The 1947 Partition of India

"Session 44: Understanding the Forced Migration of Trafficked Persons and Refugees", Population Association of America 2004 Annual Meeting Program - Hindus in South Asia & the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights, 2013. Hindu American Foundation. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016.

- D'Costa, Bina (2011), Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia, Routledge, p. 100, ISBN 978-0-415-56566-0

- "Area, Population, Density and Urban/Rural Proportion by Administrative Units", Statistics Division, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics, Government of Pakistan, archived from the original on 17 December 2003

- "Census of Bangladesh". Banbeis.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- Guriro, Amar; Khwaja, Aslam; Raza, Mansoor; Mansoor, Hasan (13 March 2016). "Caste and captivity: Dalit suffering in Sindh". Dawn.

- Long behind Schedule: a Study on the plight of Scheduled Caste Hindus in Pakistan (PDF), Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, New Delhi, 2008

- "Scheduled castes have a separate box for them, but only if anybody knew". Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Khan, Iftikhar A. (28 May 2018), "Number of non-Muslim voters in Pakistan shows rise of over 30pc", Dawn, retrieved 13 June 2020

- "Pakistan General Election: Non-Muslim voters increase by 30 percent in 5 years, Hindus most numerically significant minority", Firstpost, 22 July 2018

- Aqeel, Asif (1 July 2018), "Problems with the electoral representation of non-Muslims", Herald (Pakistan), retrieved 12 June 2020

- "How long will govt neglect Tharparkar, asks MNA Ramesh Kumar". Pakistan Today. 22 April 2017.

- "79 Hindu couples tie the knot in mass wedding". Dawn. 7 January 2019.

- Schaflechner, Jürgen (2018). Hinglaj Devi : identity, change, and solidification at a Hindu temple in Pakistan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 145,290. ISBN 9780190850555. OCLC 1008771979.

- "Cabinet approves devolution of seven ministries", Dawn, 28 June 2011, retrieved 13 June 2020

- "Asian/Pakistan - Paul Bhatti appointed "Special Advisor" for Religious Minorities", Agenzia Fides, 24 March 2011, retrieved 13 June 2020

- "Ministry of national harmony formed". The Express Tribune. 5 August 2011.

- "Concern over merger of ministries". Dawn. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Shakir, Naeem (30 August 2016), "Minorities' seats", Dawn, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Junaidi, Ikram (7 March 2019), "Bill suggests increasing minorities' seats", Dawn, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Junaidi, Ikram (3 April 2019), "JUI-F lawmaker suggests abolition of reserved seats for minorities", Dawn, retrieved 12 June 2020

- "Hindus feel the heat in Pakistan". BBC News. 2 March 2007.

- "After 1947, First Hindu Minority Woman From Thar to Become Senator in Pakistan". India.com. 21 February 2018.

- "Hindu woman elected to Pakistan's senate in historic first: Report", Times of India, 4 March 2018, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Fazili, Sana (29 July 2018), "Meet Pakistan's First Hindu Candidate Mahesh Kumar Malani to Win on General Seat", Network18 Group

- "Pakistan election: Muslim-majority areas elect 3 Hindu candidates in Sindh". Business Standard India. 31 July 2018.

- "The connection between Tamils and Pakistan", DT Next, 26 November 2017, retrieved 13 June 2020

- Shahbazi, Ammar (20 March 2012). "Strangers to their roots, and those around them". The News. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Witzel, Michael (2004), "Kalash Religion (extract from 'The Ṛgvedic Religious System and its Central Asian and Hindukush Antecedents')" (PDF), in A. Griffiths; J. E. M. Houben (eds.), The Vedas: Texts, Language and Ritual, Groningen: Forsten, pp. 581–636

- pace FUSSMAN 1977

- Akbar, Ali (4 April 2017). "Peshawar High Court orders govt to include Kalasha religion in census". Dawn. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

Kalasha, the religion followed by Kalash community, lies between Islam and an ancient form of Hinduism.

- Guriro, Amar (18 October 2016), "Struggling to revive Gurmukhi", Daily Times (Pakistan)

- Khalid, Haroon (14 August 2018), "'To see Lahore is to be born': A view of Pakistan's famed cultural heart. On Pak Independence Day, an edited excerpt from Haroon Khalid's book 'Imagining Lahore: The City That Is, The City That Was'.", Daily O (part of India Today), retrieved 13 June 2020

- Khalid, Haroon (21 July 2017), "Hindu past in an Islamic country: Living with new identities and old fears in Pakistan", The Scroll (India), retrieved 13 June 2020

- "Hindu community celebrates Diwali across Punjab". The Express Tribune. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "Dussehra celebrated at Krishna Mandir". The Express Tribune. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali (27 February 2018), "The thriving Shiva festival in Umarkot is a reminder of Sindh's Hindu heritage", Dawn, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Shah, Zulfiqar (December 2007), Information on Caste Based Discrimination in South Asia, Long Behind Schedule, a Study on the Plight of Scheduled Caste Hindus in Pakistan (PDF), Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS) and International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN), retrieved 12 June 2020

- Tarar, Akhlaq Ullah (31 March 2019), "Forced conversions", Dawn

- Javaid, Maham (18 August 2016), "State of fear", Herald (Pakistan), retrieved 12 June 2020

- "Across religious divides: A harmonious haven for Hindus in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa". The Express Tribune. 14 October 2019.

- "Sikhs and Hindu families move to Pak Punjab". NDTV. 3 May 2009.

- "Pakistan: Over 70 Hindu pilgrims from India arrive in Sindh for Sant Shada Ram anniversary". The Indian Express. PTI. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Tiwari, Siddharth (5 March 2016). "125 Indian hindu pilgrims visit Pakistan ahead of Maha Shivratri, welcomed at Wagah border". India Today. PTI. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Iqbal, Aisha; Bajeer, Sajid (10 March 2011), "Contractor blasting through Tharparkar temple in search of granite", The Express Tribune, retrieved 13 May 2020

- "Religious Minorities in Pakistan By Dr Iftikhar H.Malik" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Yudhvir Rana (4 June 2013). "Hindu parents don't send girl children to schools in Pakistan: Report". Retrieved 24 January 2021.}

- Shahid Jatoi (8 June 2017). "Sindh Hindu Marriage Act—relief or restraint?". Express Tribune. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Sindh Assembly approves Hindu Marriage Bill". Dawn. Reuters. 15 February 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Two laws govern Hindu marriages in Pakistan – but neither addresses divorce adequately". Scroll.In. 25 October 2016.

- "Pakistan approves Hindu Marriage Bill after decades of inaction". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- "Pak's Sindh to let divorced or widowed Hindu women remarry". The Times of India. 11 August 2018.

- Ali, Kalbe (27 September 2016). "NA finally passes Hindu marriage bill". Dawn. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Pakistani lawmakers adopt landmark Hindu marriage bill". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Yudhvir Rana (19 February 2017). "Pak senate's nod to Hindu Marriage Bill". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Hindu Marriage Bill Becomes Law in Pakistan". News18. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- MacLagan, Sir Edward (1926). Gazetteer of the Multan District, 1923–24 Sir Edward Maclagan, Punjab (Pakistan). pp. 276–77.

- "Ancient Pakistan temples draw devotees from across faiths". Times of India. TNN. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Pakistan to restore, hand over 400 Hindu temples". Gulf News. 13 November 2019.

- Temple turns into slaughterhouse, The News International, 10 October 2006.

- Historic Shiv Mandir makes way for a Pir , The News International, 10 October 2006.

- "Shiv temple turns into slaughterhouse in Pakistan", Hindu Janajagruti Samiti (HJS), October 2006, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Gishkori, Zahid (25 March 2014). "95% of worship places put to commercial use: Survey". The Express Tribune.

- "Hindu temple reopens after 60 ears". Rediff. 1 November 2011.

- "Pakistan to restore more than 400 Hindu temples". Dailypakistan. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "1,000-Year-Old Hindu Temple in Pakistan's Sialkot Reopens After 72 Years". Ndtv News. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Pak reopens 100-year-old temple in Balochistan". India Today. 8 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Kunal Chakrabarti; Shubhra Chakrabarti (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- Xafar, Ali (20 April 2016). "Mata Hinglaj Yatra: To Hingol, a pilgrimage to reincarnation". The Express Tribune.

- "Hindu's converge at Ramapir Mela near Karachi seeking divine help for their security". The Times of India. 26 September 2012.

- "The thriving Shiva festival in Umarkot is a reminder of Sindh's Hindu heritage". 27 February 2018.

- "Gunmen kill Hindu temple guard in Peshawar". Dawn. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Gorakhnath temple reopens for Diwali after 60 years on court orders

- "Shiv Ratri begins at Peshawar temple". The Express Tribune. 18 February 2015.

- "Mob sets fire to Hindu community center in Pak over blasphemy", Firstpost, 16 March 2014, retrieved 27 January 2020

- "Hindu teacher attacked, temple vandalised in Pakistan's Sindh". City:Islamabad. India Today. TNN. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Another Hindu temple vandalised in Pakistan, holy books, idols burnt". Wionews. 27 January 2020.

- Ahmad, Imtiaz (30 December 2021). "Hindu temple in Pakistan vandalised, set on fire". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Gannon, Kathy (28 December 2020). "Each year, 1000 Pakistani girl forcibly converted to Islam". Associated Press. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Inayat, Naila (15 February 2017). "Pakistan Hindus lose daughters to forced muslim marriages". USA Today. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Javaid, Maham (18 August 2016), "State of fear", Herald (Pakistan), retrieved 12 June 2020

- Quratulain, Fatima (19 September 2017), "Forced conversions of Pakistani Hindu girls", Daily Times (Pakistan), retrieved 20 January 2019

- Daur, Naya (16 September 2019), "Who Is Mian Mithu?", Naya Daur Media (NDM), Pakistan, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Ilyas, Faiza (20 March 2015), "265 cases of forced conversion reported last year, moot told", Dawn, retrieved 20 January 2019

- Ackerman, Reuben; Rehman, Javaid; Johns, Morris (2018), Forced Conversions & Forced Marriages in Sindh, Pakistan (PDF), CIFORB, the University of Birmingham

- Tunio, Hafeez (9 October 2019), "PPP lawmakers turn down bill against forced conversions", The Express Tribune, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Malik 2008, p. 183-187.

- Avari 2013, pp. 66–70: "Many Hindu slaves converted to Islam and gained their liberty."

- Sohail, Riaz (2 March 2007). "Hindus feel the heat in Pakistan". BBC. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

But many Hindu families who stayed in Pakistan after partition have already lost faith and migrated to India.

- "Gujarat: 114 Pakistanis are Indian citizens now". Ahmedabad Mirror. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Rizvi, Uzair Hasan (10 September 2015). "Hindu refugees from Pakistan encounter suspicion and indifference in India". Dawn.

- Haider, Irfan (13 May 2014). "5,000 Hindus migrating to India every year, NA told". Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "Why Pakistani Hindus leave their homes for India – BBC News". BBC News. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Modi government to let Pakistani Hindus register as citizens for as low as Rs 100 | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". Daily News and Analysis. 17 April 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Mandhro, Sameer; Imtiaz, Saba (21 January 2012), "Mass conversions: for Matli's poor Hindus, 'lakshmi' lies in another religion", The Express Tribune, retrieved 12 June 2020

- "Pakistan to restore, hand over 400 Hindu temples", India Today, 10 April 2019, retrieved 11 April 2019

- Mandhro, Sameer (23 January 2012), "100,000 conversions and counting, meet the ex-Hindu who herds souls to the Hereafter", The Express Tribune, retrieved 20 January 2019

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0300101478. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

separate electorates for minorities in pakistan.

- Rehman, Zia Ur (14 December 2016), "Christian community campaigns for right to elect, not 'select'", The News International, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Pakistan, International Religious Freedom Report 2006, US Department of State, 15 September 2006, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Gordon, Sandy; Gordon, A. D. D. (2014). India's Rise as an Asian Power: Nation, Neighborhood, and Region. Georgetown University Press. pp. 54–58. ISBN 9781626160743. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Khalid, Haroon (14 November 2019). "How the Babri Masjid Demolition Upended Tenuous Inter-Religious Ties in Pakistan". The Wire. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Pakistanis Attack 30 Hindu Temples". The New York Times. 7 December 1992. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

Muslims attacked more than 30 Hindu temples across Pakistan today, and the Government of this overwhelmingly Muslim nation closed offices and schools for a day to protest the destruction of a mosque in India.

- Imtiaz, Saba; Walsh, Declan (15 July 2014). "Extremists Make Inroads in Pakistan's Diverse South". The New York Times.

- "Persecution of religious minorities in Pakistan", Zee News, Zee Media Corporation Ltd., 21 October 2013, retrieved 18 February 2014

- Press Trust of India (12 July 2010). "Hindus attacked, evicted from their homes in Pak's Sindh". The Hindu. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "Hindus attacked in Pakistan". Oneindia.in. 13 July 2010.

- "Hindu temple guard gunned down in Peshawar". Newsweek Pakistan. AG Publications (Private) Limited. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "Are Hindus in Pakistan being denied access to temples?". rediff.com. PTI (Press Trust of India). 27 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Sahoutara, Naeem (26 February 2014). "Hindus being denied access to temple, SC questions authorities". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Pak SC seeks report on denial of access to Hindu temple". Press Trust of India. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Nayyar, A.H. and Salim, A. (eds.)(2003). The subtle Subversion: A report on Curricula and Textbooks in Pakistan. Report of the project A Civil Society Initiative in Curricula and Textbooks Reform. Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Islamabad.

- Hate mongering worries minorities Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Times (Pakistan), 2006-04-25

- In Pakistan's Public Schools, Jihad Still Part of Lesson Plan – The Muslim nation's public school texts still promote hatred and jihad, reformers say. By Paul Watson, Times Staff Writer; 18 August 2005; Los Angeles Times. 4-page article online, retrieved on 2 January 2010

- Mir, Amir (10 October 2005), "Primers Of Hate – History or biology, Pakistani students get anti-India lessons in all their textbooks; 'Hindu, Enemy Of Islam' – These are extracts from government-sponsored textbooks approved by the National Curriculum Wing of the Federal Ministry of Education", Outlook (Indian magazine), retrieved 2 January 2010

- Noor's cure: A contrast in views; by Arindam Banerji; 16 July 2003; Rediff India Abroad Retrieved on 2 January 2010

- Yousafzai, Arshad (18 December 2016), "Non-Muslim students reluctant to study Islamic studies or ethics", Daily Times (Pakistan), retrieved 12 June 2020

- "Ethics as an alternative subject to Islamiat in KP", PakTribune, 1 March 2015, retrieved 12 June 2020 Alternative URL

- "7 Non-Muslim cricketers who played for Pakistan". Cricket Country. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Snooker: Perwani defeats Anwar to win Cup". The Express Tribune. 6 January 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "56 candidates vie for 15 Hindu Council seats". The Nation. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- "In a first, Pakistan appoints Hindu woman as civil judge", The Express Tribune, 28 January 2019

- Ashfaq Ahmed (4 September 2019). "Pushpa has become the first Pakistani Hindu girl to serve as police officer in Sindh". Gulf news. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Women activists stress need for transformative feminist leadership". The Nation. 20 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

Further reading

- Avari, Burjor (2013), Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A history of Muslim power and presence in the Indian subcontinent, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-58061-8

- "Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan's Religious Minorities" by Farahnaz Ispahani, Publisher: Harper Collins India

- Yaqoob Khan Bangash, Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (13 June 2016), "Our vanishing Hindus", The Express Tribune, retrieved 12 June 2020

- Malik, Jamal (2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. BRILL. ISBN 9789004168596.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hinduism in Pakistan |